In 1983, veteran Fort Worth journalist and movie historian Michael H. Price — then a film critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram — received a phone call from his friend G. William Jones, director of the film and video archives at SMU. Jones, who died in 1993, had himself received a call from the manager of a dusty old warehouse in Tyler, where a large stack of nitrate film stock canisters had been discovered. After hearing some of the details of the findings, Jones had welcome news for Price.

“He said, ‘I think we found The Blood of Jesus,’ ” recalled Price. “And my response was, ‘Jesus, really?!’ ”

Believed by movie archivists to have been lost forever, The Blood of Jesus (1941) was the intense, eerie feature debut of producer-writer-director Spencer Williams, one of a handful of African-American auteurs who made so-called “race movies” –– films created by black artists for segregated black moviehouses in the 1930s and ’40s. (Williams is best known to mainstream audiences as Andy Brown from the controversial 1951 TV version of the long-running radio show Amos ’n’ Andy.) Price and Jones hopped in a car and trekked to Tyler. Price recalls the scene in the decrepit, crowded old warehouse as “a cross between King Tut’s tomb and the egg pod scene in Alien.” The two movie geeks quickly realized that the old film canisters contained director Williams’ complete nine-film collaboration with Al Sack, the Dallas-based producer whose Sack Amusement Enterprises specialized in micro-budget genre movies for niche ethnic audiences, including African-Americans and Jews. The discovery become nationally known as the Tyler Black Film Collection and is currently housed at SMU’s Hamon Arts Library.

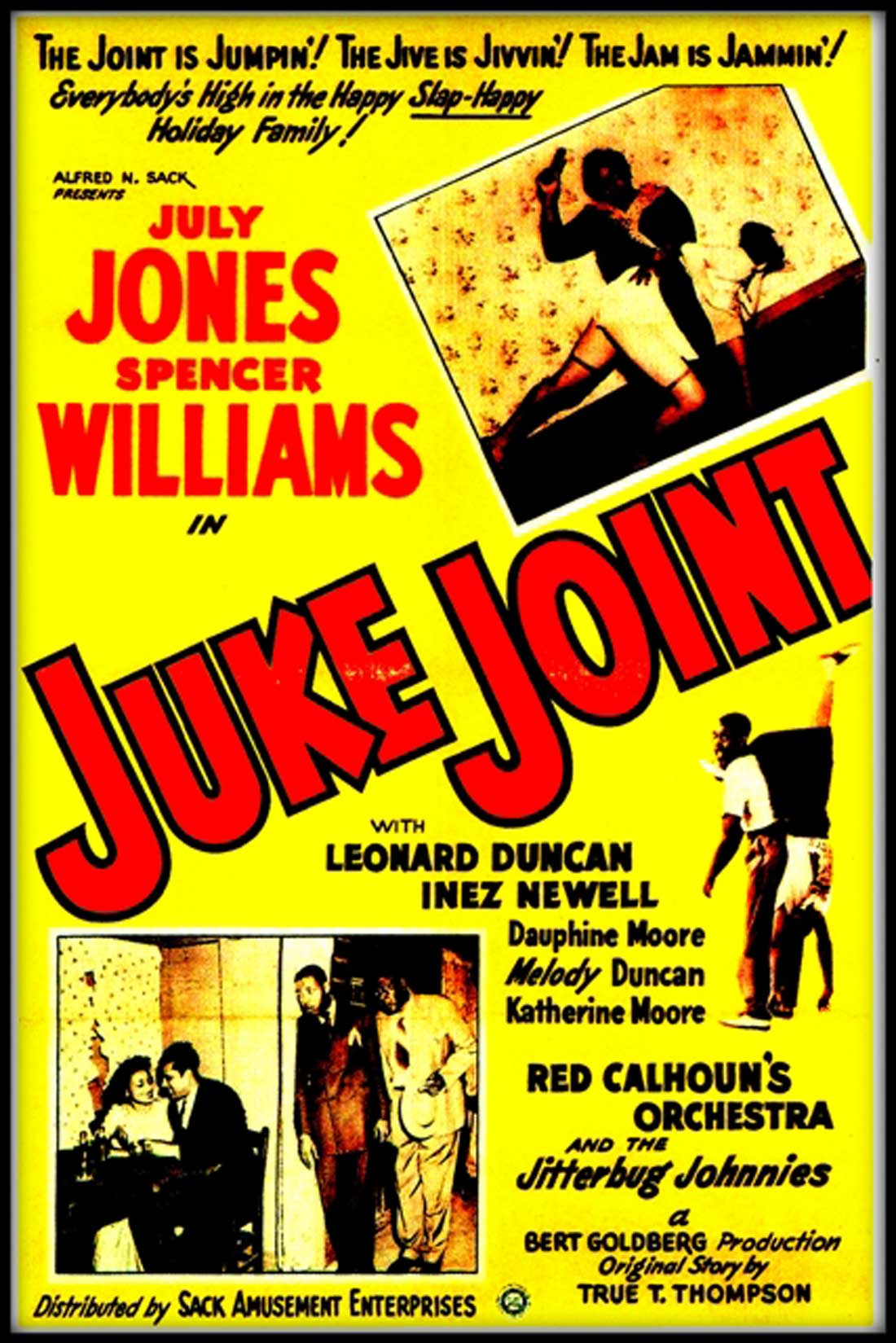

Fast-forward to 2014: Price, still a journalist, writing for the Fort Worth Business Press and author of the long-running Forgotten Horrors movie history series, is a co-founder of the Wildcatter Exchange, a new arts collective dedicated to celebrating storytelling in all media. This week Wildcatter will host a screening and panel discussion of one of the Williams-directed features discovered back in 1983. Juke Joint (1947) is a musical comedy co-starring Williams and comedian July Jones as a pair of con artists who hoodwink a family with a beautiful daughter. Like many of the Sack Enterprises productions, it was filmed on a shoestring budget in various locations in Fort Worth, Dallas, Waxahachie, and San Antonio.

“We wanted a film that would represent the importance of the Tyler Black Film Collection to North Texas,” Price said. “It’s a comedy, and it’s also a showcase for the indigenous jazz of the Red Calhoun Orchestra, which played often in Fort Worth and Dallas in the 1940s. Also, rarely do you see black middle-class family life in Texas portrayed on film, from that or any era, and here it is.”

While entertaining, Juke Joint is also very much a movie of its time and place, which means some of the broad comic performances and situations reflect racial stereotypes that 21st-century movie audiences may find, in Price’s word, “grating.” To discuss the film’s complex content and history from various angles, Wildcatter has assembled a noteworthy panel of authors and historians that, along with Price, includes Gloria Austin, president of Fort Worth’s National Multicultural Western Heritage Museum; Bob Ray Sanders, the veteran Star-Telegram columnist who broke the news of the discovery of the Tyler Black Film Collection; Fort Worth musician and business owner Sumter Bruton; and Josh Alan Friedman, the musician and author whose 2009 memoir Black Cracker, about being the only white Jewish kid at the last segregated black elementary school in Long Island, was reissued as an e-book this year.

With the screening and panelist chat for Juke Joint, Price hopes to generate an informed, passionate discussion with audience members about America’s troubled racial history and its intersection with popular entertainment. He recalls attending another public screening of the film years ago, when filmgoers had diverse reactions.

“One white audience member raised his hand and said, ‘Doesn’t this film contain demeaning representations of African-Americans?’ ” Price remembered. “Then an African-American audience member raised his hand and answered, ‘Well, that’s the way it was back then.’ ”

[box_info]

Juke Joint

6:30pm Sat at the Gladney Center for Adoption, 6300 John Ryan Dr, FW. Free.

817-922-6000.

[/box_info]