Middle-schoolers surely got a kick out of the fact that Windsor producers chose Gainesville Junior High School as the stand-in for a prison. And they probably chuckled at the sight of men dressed like inmates, lifting weights outside on one of the hottest days of the summer. With the help of fake barbed wire and crafty camera work, Gainesville Junior High perfectly resembled a Southern prison yard.

“This old school looks pretty institutional,” Farrell said, watching the scenes on a monitor under a tent that provided glorious shade.

Two weeks of shooting had left his face cherry-red with sunburn. He’d draped a yellow bandana over his head for relief and occasionally doused his head with ice water. The extras, working in exchange for free Gatorade and the thrill of being on the big screen, if even for a few seconds, didn’t have the luxury of shade. One of the extras, an overweight man of about 40, appeared close to fainting.

“They probably wish they were in prison,” Farrell said.

The overweight man said he volunteered as an extra because he is a screenwriter looking for a break. He figured he could network and make connections. Instead, he looked like he needed some intravenous rehydration.

The school is a block away from a railroad track, and the sound of trains passing by kept interrupting shots. If it wasn’t trains, it was planes. Or clouds would drift by and block the sun, bringing filming to a halt.

Eventually they finished the scene, and the crew prepared to move all the equipment to the town square. The city of Gainesville closed down Commerce Street near downtown so that Farrell and his crew could transform the red-brick road into Main Street for his fictional town of Windsor.

Even with all the freebies he’s received from the locals, Farrell was still gushing green. He paid to put up cast and crew at the Comfort Suites and to have meals catered for them. He spent a small fortune just keeping ice chests loaded with cold Gatorade and bottled water. The myriad expenditures add up to a hefty bill, and that’s why most movies never get made.

While filmmakers are getting excited about the boost in the state’s incentives, they’re also facing a political reality. Things change. Perry was an advocate for the film industry, but he chose not to run for governor again. The two candidates to replace him –– Wendy Davis and Gregg Abbott –– might have different ideas about film incentives. The Texas Film Commission is housed in the governor’s office. Neither candidate returned phone calls seeking comment for this article.

The general feeling is that the Republican, Abbott, will look more favorably on the program than Davis, the Democrat. Still, Davis comes from an acting background. Her father, Jerry Russell, founded Stage West theater in 1979 in Fort Worth.

Texas-based film industry lobbyist Lawrence Collins was a central figure in convincing lawmakers to increase the state’s incentives. But he also knows that pushing too hard for funding can turn off some supporters.

“We’re not the most competitive, but we are a very strongly looked-at state now,” he said. “Louisiana and Georgia give away the farm. Texas has a film program that comports with the fiscal conservatism of the state, and that’s a good thing.”

Executive producers, however, aren’t generally concerned about political dances. They’re seeking deals.

“The first question I get asked when somebody’s shopping around is, ‘Tell me about your incentives,’ ” said Gary Bond, the Austin Film Commission’s director of marketing. “It’s more incentive-driven than location-driven.”

He reminds filmmakers that while this state’s percentage might be lower than what’s offered elsewhere, Texas issues its money on the back end via rebate. Most other states offer a tax credit reduced somewhat by administrative costs.

Explaining the fine print and the intangibles goes a long way toward convincing filmmakers to work in Texas, he said.

So far, news has spread slowly.

“When I talk to producers and ask why they don’t want to come here, it’s because of the money, the higher cost of filming here,” said Rio Zumwalt, second assistant to the cinematographer on Windsor.

Zumwalt lives in Austin and, at 21, is just embarking on a film career. She’s found steady work in Texas on low-budget feature films and is happy to remain here for now.

“I’ve been told to go to L.A. and get connections, but I’m starting from Austin, and it’s been working well for me so far,” she said. “There are certain crews in Austin that get booked for the big union shows, and that’s where you make the majority of your money. But if I went somewhere where there was a bigger market, I could probably make more money faster.”

Unless Austin or Fort Worth becomes the new Hollywood South, she’ll probably go looking for a bigger pond one day, and L.A. is still the biggest.

The question is, how long will L.A. remain the pinnacle, and which states will work hardest to steal its jobs and workers? Farrell’s next movie is about Fort Worth, and he plans to film it here. He anticipates a bigger budget, which might earn him a higher rebate — if the legislature funds the incentive program again and if the newly elected governor favors it.

If not, well, wouldn’t it be weird to watch a movie about Fort Worth that’s filmed partly in Shreveport?

“I was courted heavily by Louisiana to shoot [Windsor] over there,” Farrell said.

First though, he has to finish Windsor. Making a movie is time-consuming, with each day presenting a long list of problems. Farrell solves one after another, such as having an assistant interrupt lunch one day with a warning. Seems an employee at the middle school complained about seeing one of the crew urinating outside.

“If you need to relieve yourself, please do it inside,” the assistant said.

That afternoon, the young cast members settled into lawn chairs along the fake Main Street, getting ready to film a crucial scene. Their characters are supposed to be drinking beer, although the actors drank water poured into empty beer bottles. They studied their lines and talked quietly. In the scene, Corbin’s character is supposed to join their little party and tell them some important news. This was the first day Corbin had filmed with all of the young actors at once.

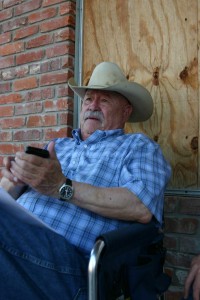

“Hi, I’m Quinn,” Shephard said as the grizzled 73-year-old Corbin sat down with them before shooting began.

“Hi, I’m Barry,” he said. “We’re going to have fun.”

Corbin spotted a friend standing nearby and said, “Don’t I fit right in here? It’s like we’re all classmates.”

Then he told a story about how his favorite horse, Smitty, had died not long ago. “I had his tail made into a bolo tie,” he drawled.

The young actors listened with smiles, while the crew bustled about, Farrell readied for the scene, the sun edged closer to the horizon, and the sound of an airplane approached from somewhere in the sky.

[box_info]Look for profiles of the actors featured in this week’s cover story on our Blotch Blog.[/box_info]

Good story, Mr. Prince. Hit it squarely and banged it over the fence.

Very nice, Jeff. Crossing my fingers for Windsor’s success.