This week is your last chance to catch Ansel Adams Masterworks, a series of original, spellbinding photographs curated by the legendary photographer during the twilight of his career. Along with some of his most recognizable pieces, such as “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico” and “Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, Yosemite Park, California,” the exhibit at Arlington Museum of Art also includes snaps of a Buddhist cemetery in Maui and of children in a California trailer park. Though Adams is best known for his work in the American West, he also trained his camera on locations as varied as Alaska, Texas, and Cape Cod. Masterworks is not only a great celebration of Adams’ legacy but also a staunch rebuttal to the suggestion that he was a one-trick pony.

Masterworks dates back to 1978, when California gallery owner Maggi Weston approached Adams, who at the time had been taking photographs for nearly 50 years, with the idea of a survey of pre-eminent works. Adams agreed, selecting and printing 70 pieces. Arlington has 48 of them, “the best of the best,” said AMA executive director Chris Hightower. Adams died six years after completing the project.

The pieces are smallish, probably to draw viewers into the details. In keeping with Adams’ minimalist style, the photos are matted in stark white and framed in black. The lighting is appropriately subtle. The work doesn’t need much augmenting.

Adams grew up in San Francisco during the early part of the last century among natural wonder (the sea and sand dunes of the California coast) and natural disasters (the earthquake and Great Fire of 1906). He had a well-documented solitary nature and the equivalent of an eighth-grade education. After Adams’ limited success in public schools, the artist’s father tutored him at home and encouraged in his son a love of the outdoors.

Adams taught himself to play piano when he was 12, and in the 1920s, he was a struggling pianist with a photography hobby. Hightower said that Adams’ passion for music made him “a conductor in the darkroom.” Adams credited his dexterity with a camera to his training as a pianist.

In the late 1920s, Adams had started photographing the Sierra Nevada Mountains and Yosemite National Park, and Sierra Club Bulletin published many of his early works. Over the next five decades, Adams and the Sierra Club were inextricably linked. Adams spent so much time in Yosemite that he had a darkroom built there. In 1937, a fire ravaged the room, destroying a third of his early negatives.

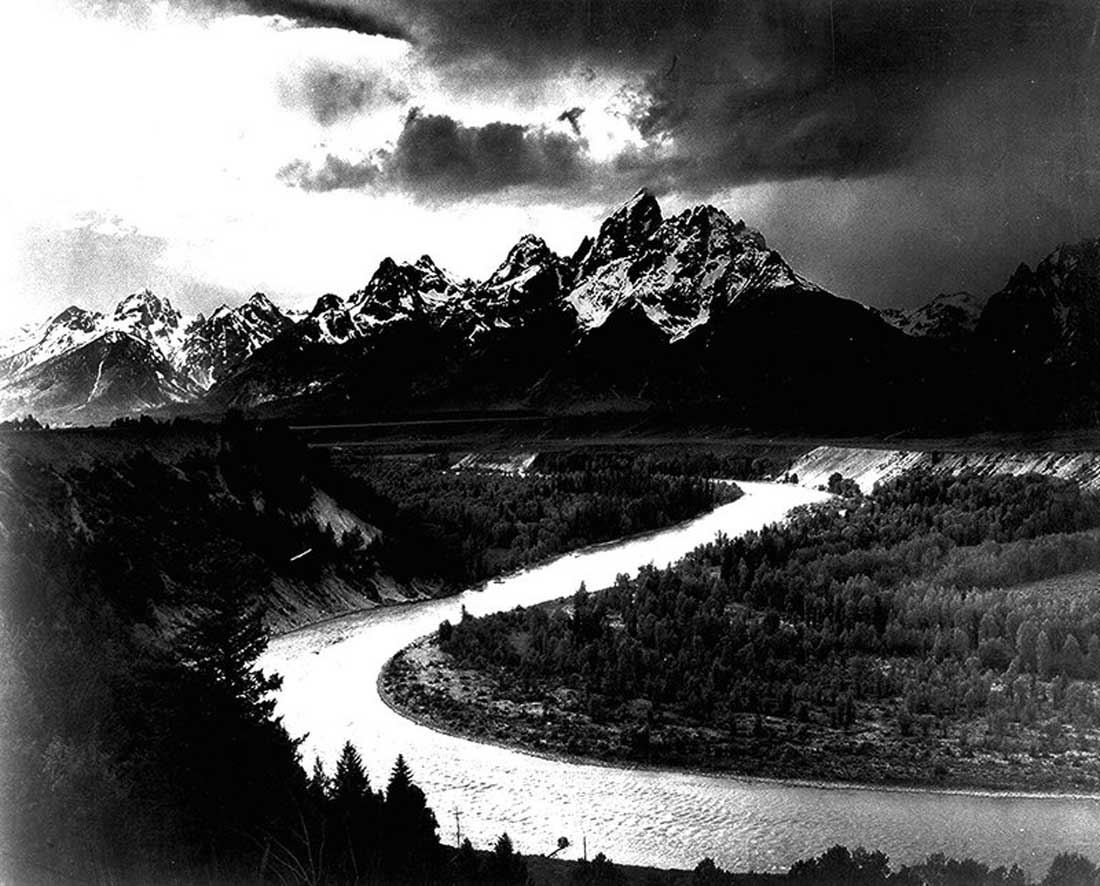

Much of Adams’ work in the early 1940s was on commission from the National Department of the Interior for a series of murals. When his commission was not renewed, Adams sought other support to continue to travel and photograph the nation’s national parks and wilderness areas. It was during this time that a Guggenheim fellowship allowed him to travel to Big Bend National Park. “Sand Bar, Rio Grande, Big Bend National Park” is from his time there, and while it’s not one of his best works, it is illuminative, a snapshot of what the river looked like more than 60 years ago. The pristine water is shimmering, and the surrounding land looks like velvet.

Adams and fellow photographer Fred Archer are credited with successfully applying the principles of the zone technique: playing with the exposure and further influencing light and shadow by controlling the amount of time areas of a picture were immersed in the chemicals in the darkroom.

The play of light, exposure, and shadow makes the sky in “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico” dark, while the dying light of the sun seems to glint hauntingly on white grave markers below. It’s also what makes the ghostly, almost phosphorescent trees glow in “Aspens, Dawn, Dolores River Canyon, Autumn, Colorado.” Although other photographers used the technique, it was Adams’ mastery of it that made his work so identifiable. The caption accompanying “Moonrise” in the exhibit uses Adams’ own words to describe both the zone and the incredible dexterity and luck needed to capture what’s become an iconic slice of Americana.

Despite his prolific output, Adams spent decades without making a significant income. As he said, he couldn’t “seem to climb over the financial fence.” The man regarded as an inspirational nature photographer also worked as a commercial photographer to pay bills.

Adams played a key role in the development of the department of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. His body of work was so strong that museums whose curators normally wouldn’t deign to show photos regularly exhibited Adams’ work. New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art held an Adams retrospective in 1974. In 1983, Adams was the first American artist to have an exhibit at the National Museum in Beijing.

His work received criticism in the latter portion of the 20th century as other artists were photographing the cultural and political upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s. Adams was singled out as an idealist who never included pictures of people in his photographs. This is not technically true. Adams went to the Manzanar Internment Camp in 1943, when thousands of Japanese-Americans had been displaced after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He documented the lives of the internees and published the photographs in 1944 in a book, Born Free and Equal. But pictures of places indeed far outnumber pictures of faces in Adams’ photography, an unabashed continuation of the environmental activism of Henry David Thoreau and John Muir. During his lifetime, Adams had contact with almost every single president of the United States, from Franklin Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan. He used each opportunity to remind people in power of their responsibilities to the nation’s natural treasures. When he died in 1984, Congress designated a 200,000 acre area near Yosemite National Park as the Ansel Adams Wilderness Area.

[box_info]

Ansel Adams Masterworks

Thru Sun at Arlington Museum of Art, 201 W Main St, Arlington. Free-$8. 817-275-4600.

[/box_info]