“I’m going to paint over that one,” artist JT Grant said, pointing to a large canvas hanging high on the 14-foot white wall of his backyard studio in Fairmount. “It’s pretty old. It hasn’t sold. I have something different to say now.”

Like centuries of master artists before him, who painted over old or unsatisfying paintings, Grant will reuse this canvas, which features a lithe, pale figure of a woman. Her face is covered with strips of white linen, as are her shoulders and breasts. One loose white sash flutters near her waist. She holds a hunting rifle in one outstretched arm. The gun as a symbol? A blindfold and other bindings? Her half-nakedness representing vulnerability?

Grant, 58, dismisses these attempts to interpret the work. “Like I said, I’m over this painting.” The dismissal is gentle but resolute.

“What I’m doing now is more angry, more edgy,” he said. “The core of my life and philosophy is essentially the same, but my experiences are different and my grief is palpable now.” He feels equally grateful and discontented over the recent trauma he has survived. “That I feel lucky sounds ironic, but that’s part of the truth. I’m also very angry. I don’t dwell on it, but I acknowledge it.”

It’s been three years since Grant’s primary physician told him he had 72 hours to live, from a malady that to this day has only been partially diagnosed. “It’s a combination of things, some cured now, some I’ll have to live with,” Grant said.

His health crisis left one of Fort Worth’s most acclaimed artists too weak to move from the sofa in his studio, unable to lift his right arm to paint higher than half-way up a canvas, and in the grip of severe pain and weakness. “I lost 80 pounds overall,” he said, “but I’ve regained 22. I was 6-foot-1¾ inches, and at the last measurement I was 5-foot-10.”

People still call him the “gentle giant,” and he’s maintained his regal bearing. There’s a new haunted quality to his hazel eyes.

If you didn’t know him before, you’d still get a sense of confidence in his bearing. In addition to having shrunk a couple of inches and losing so much weight, his face seems more open — and wise and tired. You might detect the faint tremor in his hands, though.

“I’ve always had a slight tremor,” he said. “It goes away when I paint.”

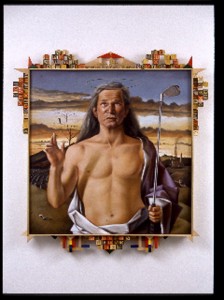

Only Grant’s closest friends and family knew about his ordeal; he hasn’t spoken publicly about it until now. His first solo exhibit since his illness opens May 3 at William Campbell Contemporary Art, which has represented him for many years. He’s taking a new tack in some of the paintings, allowing images and objects to deteriorate into the background — qualities that he acknowledges are related to what he has been through.

“The edges start to fade or break up,” he explained. “This work is much darker to me, although the difference may or may not be obvious to others.”

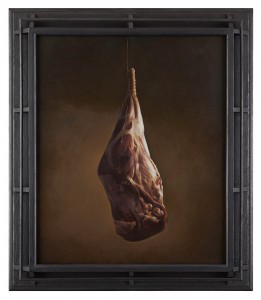

With images that manage to be intense without being self-conscious, Grant doesn’t load up his canvases with private torment. Lush and painstaking, his work does hark back to the Old Masters — Rembrandt, Vermeer, Rubens. His extraordinary use of light; earthy, rich color choices; and meticulous brushwork recall the classicists. He also favors human figures, painting people big as a rule, on big canvases, so that heads, arms, necks, and torsos are virtually life-size.

Comparisons to the Old Masters make him uncomfortable. “I’m certainly no Rembrandt,” he said, laughing. “Rembrandt did paint a lot of portraits, and I do, too. I don’t stick exclusively to portraiture, and he didn’t either. I suppose that he did what was necessary for him as an artist and a person. We are alike in that.”

Grant is driven, and he admits his period of illness and confinement has given him a different self-perception. “My passion is painting. Painting is my life,” he said. “I knew that before, but I now know the degree to which I will fight for it. I will never give up the pursuit of art.”

********

The task of picking a college for his master’s studies brought Grant to Fort Worth in 1992. He’d grown up in tiny, rural Montrose, Va. “My earliest memory of art was around age nine,” he said. “I would put a piece of wax paper over [depictions of] classical paintings and trace them with an empty pen.” At 12, he said, he remembers painting a landscape from a “how-to” book — the Matterhorn in a field of snow with a sunset background.

“You ain’t seen the Mona Lisa until you’ve seen it etched into a sheet of Cut-Rite,” he quipped in mock Southern drawl. “My uncle paid me a dollar for the Matterhorn.”

He earned his bachelor of fine arts degree from Virginia Commonwealth University and then headed to Texas Christian University, where he received his MFA in 1994.

“I knew I could make it in Fort Worth after being awarded best in show for two years in a row in the Art in the Metroplex competition,” he said. The first juror to select Grant was Luis Jimenez; the second, James Surls. Shortly after this recognition by two of Texas’ most respected artists, Grant met Bill Campbell.

“He invited me to be part of his stable after he saw my thesis show at TCU,” he recalled. That sort of reinforcement told Grant he was in the right place at the right time. Campbell has been his friend and gallerist for 20 years now.

“This region responded very positively to my quirky edginess, and I’ve made a home for myself here,” Grant said. His parents moved here in 1985. His father is 88; Grant lost his mother in January.

In this town, he said, “I’ve enjoyed meeting the best friends I’ve ever known. I’ll kill and stuff them all so I can take them with me when I finally retire to a beach somewhere.”

Over the years, Grant restored an old home in the Fairmout neighborhood, became content in a relationship with his partner, and became a committed artist. In the summer of 2010, his health suddenly began to fail.

“I lost eight pounds one week, 10 the next week, and then another eight,” he said. He was concerned, but his closest friends were frightened. “I had other symptoms all at once, and ultimately my friends got me into the JPS system.”

The cadre of medical specialists in the JPS Health Network prodded him, did MRIs and CT scans, analyzed blood tests, and discussed Grant’s fairly mysterious symptoms and indications. “I was seen by an orthopedic surgeon, ENT surgeon, endocrinologist, neurosurgeon, and a hematologist. They are still not completely sure what was going on or what might continue,” Grant said. “They’ve told me that a lot of the neuromuscular diseases like multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis have similar symptoms in the very early stages. But not everything that’s characteristic of those conditions has happened to me.”

On both sides of Grant’s extended family, MS and ALS, often referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease, have reared their decidedly ugly heads.

Doctors say he definitively has Addison’s disease, a rare chronic endocrine disorder, and he did have a profound intestinal infection caused by the aspergillus fungus that likely found its way into his system via chronic sinusitis.

His shoulder condition, the result of a sudden separation and atrophy of the muscles that hold the scapula down to leverage the arm for lifting and reaching, was alleviated with surgery, and he’s had two sinus operations. He is managing arthritis and osteoporosis, not knowing whether these problems were compounded by his health crises and steroid medications or whether they’re simply a common part of growing older.

“I guess at first we thought he had the aches and pains of getting older,” said Bill Campbell. “Then we began to worry. Then we just wanted to help him.”

Campbell and his wife, Pam, a certified art appraiser and partner in the gallery, stepped in during the worst of Grant’s crises. “He’s just another kid to us, like one of our own,” Bill Campbell said. “Since he didn’t have anybody to lean on locally, we were just people he trusted, and he let us help him.”

The gallery owner noted Grant’s innate shyness and reluctance to ask for help of any kind. “He’s a very private person and guarded in a way that’s to a fault sometimes,” he said. The Campbells stood by in the surgery waiting room each time Grant needed them. Bill stayed with him overnight, and Pam took meals and her computer to Grant’s house to work while he recovered.

“I was able to take a few commissions even during the worst of it,” Grant said. At one point, he rigged a makeshift brace to support his arm so he could paint. Another time, he laid a canvas on the floor in order to reach all of it.

Pam Campbell remembers gallery clients wanting to commission new work or peruse the inventory of Grant’s paintings during that period. “We always have a few of JT’s pieces, but not many,” she said. “He tends to spend a lot of time on each canvas, so even though he’s been prolific over the years, we didn’t have much of a collection.”

Grant sold the bulk of his paintings on hand to a client in England. “She bought nine paintings for her apartment in London, and then everything I had in reserve was sold.”

********

JT is definitely an idol of mine. I’m sure I am not the first artist he has inspired. Best wishes as you move into your next paintings. Thank you Annabelle for a wonderful article.

Such beautiful prose & insight into one of the greatest masters in painting of this generation. I’ve not often read a story so lovingly written that captured the very essence of the person being profiled. Kudos, Annabelle for such brilliant writing that is on a par level with JT’s soul & artistry. I’ve always treasured our works by Grant, celebrated the placements in clients homes & felt strangely paternal upon securing a commission but this story and the depth of his personality increases all those feelings tenfold. I was once able to share one of his great works with a very respected businesswoman in town that holds my highest regard for her business acumen, extreme integrity & impeccable standards……..now that “gift” has even greater meaning as the best of the best hangs in the home of the best of the best!