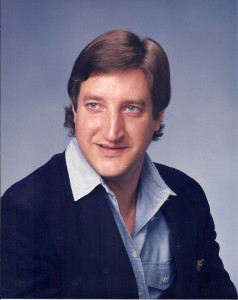

Maurice Dutton understands the feeling of complete helplessness in the face of mental illness. His son Michael was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 14. Three years later, in 1980, he was involuntarily admitted to Austin State Hospital after local facilities proved inadequate to help him. For the rest of his son’s life, Maurice watched Michael’s painful journey through Texas’ mental health and prison systems.

After several weeks, Michael’s condition had stabilized sufficiently to allow him to be released from the mental hospital. He managed a fairly stable life through most of his 20s, although his paranoia led him to quit jobs again and again. Living on his own for the first time, he made friends with drug users, and his already dim hope for the future began to wink out.

Convicted of assault in 1987, Michael was placed on probation with the requirement that he receive outpatient services from the Austin State Hospital. When he confessed to a parole violation in order to get himself back into the hospital — the only place he knew to get the help he needed — he was sent to prison instead, to serve his nine-year sentence. Eventually he quit taking his medications, began lashing out at guards and fellow inmates, and ended up spending long periods in solitary confinement.

Even worse things were happening, however: When his parents visited him during his seventh year of incarceration, Michael told them he was being “abused, ridiculed, and raped.”

After his release, Michael, a frail shell of his former self, returned home to live with his parents. He died from HIV complications four and a half years later.

“When people ask me what [Michael] died of, I say neglect,” Maurice said.

Texas is sorely lacking in funds for the kinds of community resources that could have helped Michael Dutton avoid the state hospital and prison, said Beth Mitchell, lawyer and director of the advocacy group Disability Rights. She sees that lack of resources as the biggest failing of a state mental healthcare system that is fraught with problems.

“If people get the proper support in their communities, then they won’t end up with these [criminal] charges,” she said. “Texas has grown, and the system hasn’t kept up.”

Texas’ system of caring for people with mental illness has never been stellar. The state spent 23 years, from the mid-1970s to the late 1990s, under the watchful eye of federal courts because of systemic failures documented in a class action lawsuit. A settlement was reached in 1992, after the Texas Department of Mental Health/Mental Retardation (which became part of a reorganized state health department in 2003) agreed to monitor its own performance on treatment issues.

Improvements were made during those years, but they didn’t do much to permanently change the low priority given to mental health services in this state. In 2007, Disability Rights won a lawsuit to limit the length of time that individuals could be held in Texas jails awaiting mental treatment before being tried. People were being held in jail for years without getting a trial or treatment. And yet three years later, another nonprofit found that eight times as many mentally ill persons were still being held in Texas jails as in its psychiatric hospitals.

According to a 2010 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation, Texas ranks dead last among the states in per capita spending on mental health, coming in at $38.38 compared to the national average of $122.90.

But a very unfunny thing happened on the way to developing a state mental health services budget during the last legislative session: A disturbed young man named Adam Lanza killed his mother in Newtown, Conn., then drove to Sandy Hook Elementary and killed 26 children and six staffers before turning his gun on himself.

The tragedy, the latest in a seemingly unending line of school shootings in this country, apparently galvanized the Texas Legislature. As State Sen. Jane Nelson recounted it:

“Legislators began the session with a real desire to address mental health because we are hearing this message from our hospitals, law enforcement, and others,” she said. “We see that all too often these mental health cases end in preventable tragedy. It’s smarter, kinder, and more cost-effective for Texans to have their mental health needs addressed in a treatment setting than in our jails and emergency rooms.”

Colleen Horton, policy program officer at the Austin-based Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, said she’s never seen the legislature offer any agency more money than it requested.

“It was evident that the state recognized the need to devote more resources to addressing mental health,” she said.

Effects of the resulting 15 percent funding increase are evident in Fort Worth. Catherine Carlton, communications director for MHMR of Tarrant County, said her agency has been able to create a new adolescent crisis unit, decrease clients’ overall wait time for treatment, and make other improvements.

“The investment is working,” she said. “Every day we see the new funding changing lives, but we still have a long way to go before resources available in the community mental health system can fully meet the demand in our community.”

The additional funding came at a time when other factors were also tending toward change in the system. A 2010 study commissioned by the state health services agency recommended a complete overhaul of Texas’ mental health code. And when that study was done, the Hogg Foundation awarded a grant to another nonprofit, Texas Appleseed, to perform that overhaul. Appleseed is a national network of volunteer lawyers focused on serving underrepresented individuals and groups.

Together, the two studies — both led by Dr. Susan Stone, a lawyer, physician, and longtime advocate for the mentally ill — provided the basis for a package of nine bills filed in last year’s legislative session to reform the state’s system of caring for its mentally ill residents. Two of the nine passed, along with a bill that loosens the definition of who can be treated at state-funded facilities.

Horton said Texans gained a lot, not only from the bills that passed, but also from the broader discussion that Stone and Appleseed started among various mental health groups.

“If the answers are difficult, that typically means the questions are important,” she said. “Many legislative initiatives take many sessions to pass and require much debate and compromise.”

One of the successful bills went into effect in January. It adds several diagnoses to the list of mental problems that qualify persons for treatment at state facilities. The list formerly included only so-called priority populations — people with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or major depression. It now covers children and adults with post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and emotional and personality disorders.

The bill also includes provisions intended to change conditions in Texas jails and prisons by insuring that fewer mentally ill persons end up there. The “jail diversion” measures are expected to lessen the burden on the state’s crowded criminal justice system.

Advocates say stories like that of Michael Dutton, national tragedies like Sandy Hook, and an increasing shortage of hospital psychiatric beds in Texas are putting pressure on legislators, agencies, and local mental health groups to find ways to improve the state’s chronically overburdened mental healthcare system, leading to possibly the most significant changes to the system in a quarter-century.

State Sen. Judith Zaffirini, one of the sponsors of the legislative reform package, said the work is long overdue.

“There have been great advances and changes in the mental health field since 1985, when our state’s mental health laws were last revised substantially,” she said. “The code should be updated to reflect that progress.”

********

Edward, thank you for highlighting the challenges that Texas faces in mental health and in substance use; and for the successes we have made; and for spotlighting some of our champions. I especially thank you for the human dimension of your article. Let us all continue to advance recovery and wellness in Texas. Sincerely, Dr. M

What outcomes are the state’s mental health providers fostering? Do individuals who can access treatment obtain that care which makes a difference?

Joe. Good questions. There are still problems about ease and quality of access. There are more resources going into teleconferencing technology that will allow psychiatrists to assist people in remote parts of the state, a long-time problem. There appears to be more emphasis on peer-to-peer counseling and a new philosophical approach that emphasizes recovery (learning to live with symptoms) over being cured. I was also impressed to see efforts to reach children and give public school teachers mental “first aid” training.

Edward, excellent article.

This was a really excellent article about some of the mental health challenges in Texas. I’m a psych student, and I’ve found it shocking that in Texas, the prison system because the avenue of treatment for many with mental illness because of lack of resources and legislative support in Texas. This is a good start, but we should only see this as a beginning, the system is still severely broken and needs help.

Sir,

my deepest sympathies to you, your wife & any one else touched by such a tragic loss. Mental health is a complex area, but certainly not resolved in a prison environment.

If there is anything I am able to help you with please contact me on Linked-in.

Maurice Dutton

Safety Consultant

Trainer & Assessor

Cairns Australia