Even in the winter doldrums, the rekkids keep on comin’. The biggest of the bunch on the chopping block this week is from a legend who left too soon, and it’s also one of the biggest albums to come out of the 817 this season. The other two platters under review are staunchly DIY projects that couldn’t be any more different. Diversity, y’all. It’s the spice of life. –– Anthony Mariani

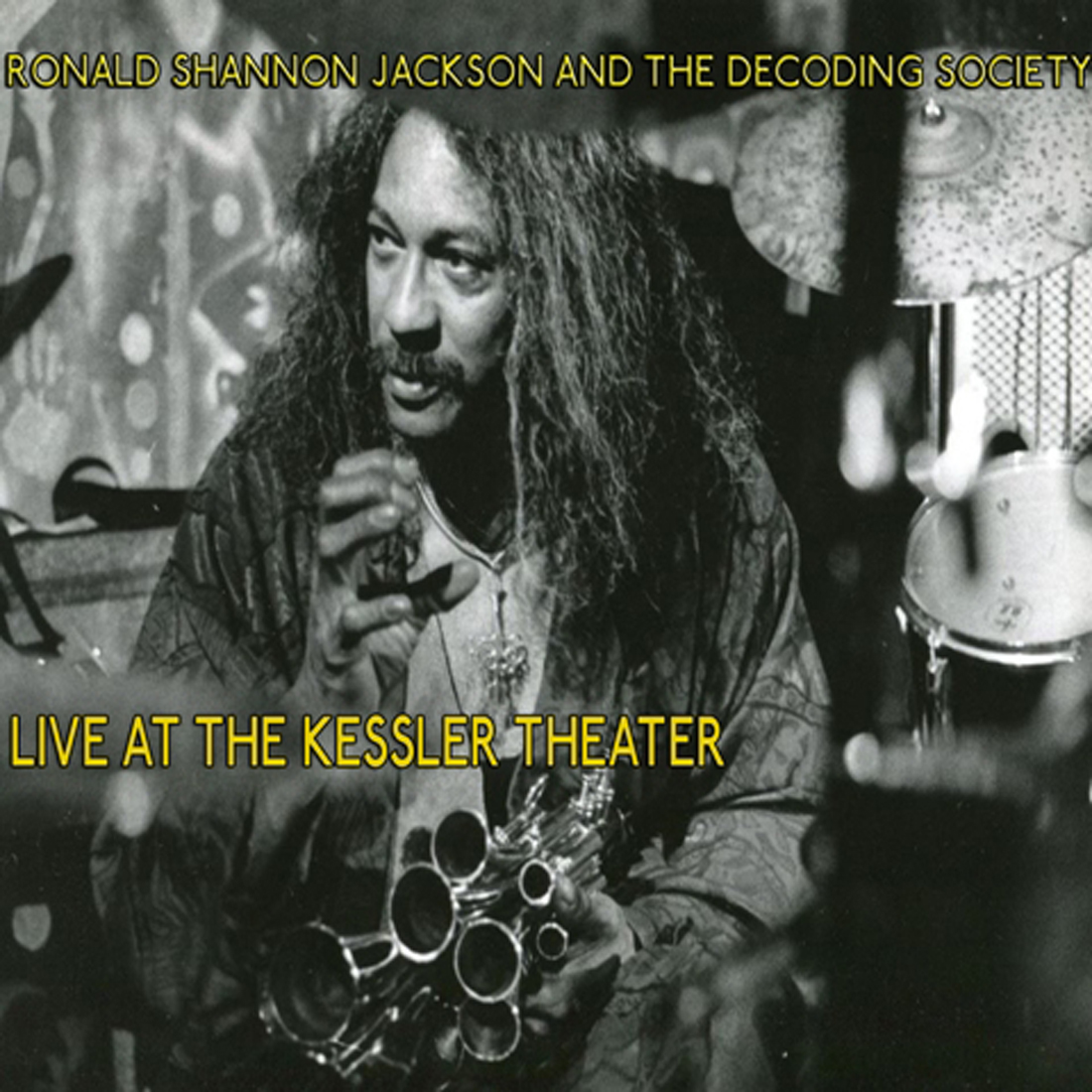

Ronald Shannon Jackson and The Decoding Society’s Live at The Kessler Theater

Before his death last October at the age of 73, jazz drummer and composer Ronald Shannon Jackson was an unstoppable force. As a child in Fort Worth, he learned the fundamentals from John Carter and, at I.M. Terrell High School, G.A. Baxter, who also taught Carter and fellow future jazz giants Ornette Coleman, King Curtis, Julius Hemphill, and Dewey Redman. After developing into an idiosyncratic virtuoso and relocating to New York City, Jackson collaborated with legends Herbie Hancock, Ornette Coleman, and Cecil Taylor, among others. In 1979 he started his own group, The Decoding Society, with violinist Billy Bang, bassist Melvin Gibbs, saxophonists Byard Lancaster and Zane Massey, guitarists Bern Nix and Vernon Reid, and percussionist Erasto Vasconcelos.

Jackson’s last performance was in July 2012 at The Kessler Theater in Dallas with Gibbs, violinist Leonard Hayward, guitarist Greg Prickett, and trumpeter John Weir. Engineered by Paul Quigg, a recording of the show has just been released by Fort Worth producers Curtis Heath and Britt Robisheaux in cooperation with Talkeye Jackson, Ronald Shannon Jackson’s executor and youngest son. Live at The Kessler Theater is Jackson’s first official recording since 2000.

The standout track is also one of Jackson’s most recent compositions. “People We Love” is the auditory version of a surrealist painting. As with a lot of his work, the harmonies here are ambiguous but not to the point of distracting listeners or, worse, distancing them. Bassist Gibbs forgoes his instrument’s traditional role of delineating harmonic changes by opening with a repeated figure that conjures up images of the Middle East. Guitarist Prickett, whose style is equally asymmetrical, alternates steadily among ambiguous, angular chords, marking time like a distressed pendulum. Out of this primordial soup, violinist Hayward emerges, delivering wide upward bursts before wilting away, defeated. His calls are assumed by trumpeter Weir, who sometimes doubles Hayward’s distressed lines or decorates the crests with slow, sparse replies. The middle third of the 9-minute track is filled with a rhapsodic solo by Weir, whose soft, reverberation-tinged handiwork seemingly begins from afar but only draws the listener closer. Weir methodically develops his improvisation into a New Orleans-style fanfare, eventually blasting the outer limits of his horn.

Behind the discordant serenity is the sage, conducting while playing. Jackson’s timing is both loose and authoritative. He understands what a drummer is supposed to do in a jazz ensemble: balance the delicate tension among the players. He knows when to hold back, chiefly while another musician is expressing an idea, and when to relentlessly propel the music forward with explosive bursts.

Beyond being a tribute to the multitudinous genres whelped by Western music (jazz, bebop, free jazz, world music, classical), Live at The Kessler Theater serves as an invaluable lesson for any aspiring musician. And a proper sendoff to a true maestro. –– Edward Brown

Ghost of John Murphy’s Voices

From the opening fade-in of electric guitars struggling to find a marriage between dissonance and melody, Voices, the debut album from Ghost of John Murphy (a.k.a. veteran Fort Worth singer-songwriters James Michael Taylor and Jeff Prince) tries to worm its way into your mind, seeking out the tuning knob to the subconscious. The signal, fluctuating between colorfulness and static, captures the imagination –– and the ears. Sometimes whether the listener wants it to or not.

The 11 tracks vary in style, from jazzy folk and a sort of tarantella sound to psychedelia and post-punk. The plinking and weaving of the guitars on the opener, “Lee Harvey,” are replaced by real audio of the infamous assassin trying to explain himself but coming across as delusional and lonely. His nonsense is quickly followed by a short, driving, guttural instrumental break with a brief acoustical refrain that gives way to Prince contemplating Oswald’s last moments aboveground, saying in his Texas drawl, “Lee Harvey Oswald was buried in Rose Hill Cemetery in Fort Worth, Texas. Nobody wanted to carry the casket.”

The rest of the album is equally wild. “Weather” is a whimsical, almost choral number about a weatherman with an uncertain forecast on relationships. “Diamond” could easily be at home on a Pink Floyd album circa Meddle, while the anthemic “No More” has the semi-monotone delivery of later-day Butthole Surfers. Other tracks, such as the haunting ballad “Small” and “The Forests of Iran” –– a spoken-word poem set to music and read by the author, Sara Behrad –– are heartbreakingly beautiful and vulnerable. With Taylor and Prince on bass and drums in addition to guitar and vocals, all of the songs are exceedingly well crafted and thoughtful. The lyrical imagery seems just as important as the tones and notes played.

Taylor and Weekly staff writer Prince have been collaborating for years, most recently as Fontanelle with their former bass player, assumedly named John Murphy, who one day sold all his gear and promptly disappeared, giving rise to this new incarnation. Though Taylor and Prince occasionally gig together around town, they don’t get out much. Hopefully, this album will change all that. –– Carey Wolff

The Hack and Slashers’ Play the Game

There are probably only a few good reasons why you’ve decided not to play Dungeons & Dragons. You could have things to do, for instance. Or be female. Or have been born to parents who totally bought into the notion that D&D somehow turned kids into Satanists or, worse, members of the KISS Army. Or maybe you looked at the combined investment of The Player’s Handbook, Monstrous Compendium, and a bunch of specialized dice and decided you’d rather blow that money on booze, because you’re almost 30 and who is going to play some stupid role-playing game with you anyway? In other words, The Hack and Slashers’ Play the Game EP is lo-fi grindcore about Dungeons & Dragons, and when it’s not that, it’s lo-fi synth music about Dungeons & Dragons. If you’ve ever spent an evening rolling 12-sided dice or at least entertained the idea, you have a +2 chance of enjoying Play the Game. Otherwise, you’ll probably just take damage. –– Steve Steward