Kaufmann usually starts his workdays around 2 p.m. He doesn’t like to bother chefs in the morning, he said, and at many dinner-oriented places, the chefs don’t come in much earlier than 2.

He doesn’t stay long. He asks how things are going, asks if his company is taking care of their needs, drops a gift, cracks a joke or two, and moves on.

On a recent weekday, wearing his FreshPoint jacket and a beret, he visited seven restaurants in the span of about three hours. His whirlwind tour included Buttons Restaurant, Winslow’s Wine Café, Clay Pigeon Food and Drink, Tillman’s Roadhouse, Fireside Pies, Rodeo Goat, and Sera Dining & Wine. At each stop, he gave the chef a small yellow gift bag with a pear and a poem inside.

At every place, the chefs stopped whatever they were doing to kiss the proverbial ring.

Damien Grober of Rodeo Goat first met Kaufmann while the younger man was a student at The Culinary School of Fort Worth.

“We were nervous because he is a legend,” Grober said. “He talked to us about how to sustain a normal life while running a kitchen.

“Now I get to see you all of the time,” he said to Kaufmann. (“He always brings something, like poems,” Grober added to this reporter, comparing Kaufmann to a philosopher.)

John Marsh, who owns and manages Sera, has been in the restaurant business in Fort Worth for 30 years. He said he sees Kaufmann as a valuable resource.

“He’s an institution,” he said. “It’s important for him to connect with a lot of the younger chefs. They need that link.

“Anyone who wants to run a successful restaurant should know Walter,” he said.

Ironically, the poem Kaufmann delivered alongside the pear was “Slow Down,” by George Carlin.

********

A man with Kaufmann’s resumé could easily rest on his accomplishments, assured of his legacy. But instead he uses his celebrity to give back to the city he said has given so much to him.

At times, Kaufmann looks as though he’s running for office, constantly shaking hands, talking to groups, and on the move.

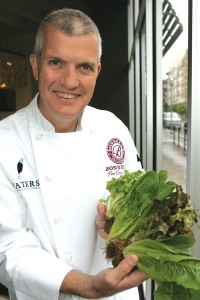

Longtime chef Tom McGrath, now a marketing associate for FreshPoint, credits Kaufmann as the driving force behind the revitalization of the Fort Worth chapter of the chefs group.

“Walter holds that group together,” he said. “One of the major roles he plays is recruiting members.”

McGrath, a past president of the association, said Kaufmann also created one of the group’s annual fund-raisers. The Walter Kaufmann Chef’s Holiday Pantry is a bake sale patterned after a similar event organized by the Dallas chapter of the Texas Chefs Association.

Now in its seventh year, the Fort Worth event has raised more than $25,000 for the Tarrant Area Food Bank’s Cooking Matters program, in which volunteer chefs and nutritionists teach nutrition, cooking, food budgeting, and shopping techniques to disadvantaged families.

“He goes out and solicits all of the donations,” McGrath said. “He basically goes door to door to the chefs and gives them all of the literature and registration forms and then follows up with them.”

Several years ago, Kaufmann gathered a group of industry people together to form the Culinary Library of Texas, which aimed to preserve menus, cookbooks, and historical documents and to act as a resource for professionals in every corner of the restaurant business, from chefs to farmers.

That project never got off the ground because organizers couldn’t agree on the direction it should take.

Heather Kurima, director of The Culinary School of Fort Worth, and a few others recently revived the idea. “Last May, a few of us who were involved in the project got back together and said, ‘We really want to see this happen for Walter, so what’s the best way to move forward?’ ” she explained.

The group re-formed as the Texas Culinary Preservation Society, with the same basic goals as its predecessor. A few months ago, the group was granted its federal nonprofit status.

Kurima said the group’s main focus is to try and draw as many food-related professional organizations into the fold as possible and to get everyone communicating.

“That would include the farmer who grew the food, the distributors who help get the food to the table, the winemaker … and everyone who touches [food and drinks].”

Kaufmann serves as president of the Preservation Society’s board. Anther of its goals, according to Kurima, who is vice president, is to help “promote understanding and professional study in the arch of the table” — meaning the full range of professions involved in the food industry. The Preservation Society’s plan is to give scholarships to culinary school for would-be chefs and to agricultural school for young farmers.

The culinary library is still alive as one component of the Preservation Society. It will be housed at the culinary school until it outgrows the space. Kurima said much of the library will also be online.

“Walter has menus from the ’70s,” she said. “If we could scan those and put them online, that would preserve them.”

********

Kaufmann has fully embraced his role as the éminence grise of the Fort Worth culinary scene. He said he’s proud of the strides the city has made since he opened his restaurant in 1964, and he’s grateful to have had the chance to play a part in turning the city into a “culinary mecca.”

“I was successful because of my head waiter, my bartender, my host, my dishwasher, and people like Betty Buckley [who sang in the restaurant],” he said. “I don’t think any restaurant owner or chef can take credit for success without acknowledging the support staff.”

He chooses his words carefully, often after a long pause and a contemplative, distant stare.

“If I could do it all again, I would, but with a few changes,” he said. “I would want my kitchen to be more of an extension of a doctor’s office and serve healthier food. When I say ‘healthy,’ I mean food that’s a close distance between the farmer and my restaurant.”

One of his biggest regrets, said, was becoming “addicted” to the restaurant business, causing him to miss out on seeing his son grow up.

“I worked six days a week,” he said. “I worked until late at night. When I got home, my son was asleep. When I woke up, he was at school. On Saturday I worked, and by Sunday I was exhausted.

“Learn to balance your life between business, family, and private life,” he said. “You have to love [the business] to succeed, but if you love it to the extent that you are addicted to it, then it’s no good.”

Kaufmann has been married to his second wife, Glenda, for 17 years. He spends time swimming at a YMCA near his Ridglea home as part of his rehabilitation from open-heart surgery two years ago that required seven bypass procedures.

One of the great joys of his life is hearing from his former customers, as he does daily.

“People would tell me, ‘We had our 20th anniversary at your place, and we had veal Oscar and bananas Foster for dessert,’ ” he said. “That is truly rewarding.”

I worked for Mr.Kaufmann @ the Old Swiss House on the trinty river.My late uncle Mr.Morris Whitaker was his right hand man back then.My mother told me on last week that I need to check out the fort worth weekly to see an old friend that I worked for,but didn’t tell me who it was…..Boy was I surprised.He helped pave the way for me not only in the fine dinning aspect but in how to give THE BEST CUSTOMER SERVICE.