In the annals of Fort Worth contemporary art, Vernon Fisher probably looms the largest. And for good reason. The veteran multimedia artist and painter is a complete badass. There’s really nothing that pops up in his head that he can’t articulate with his hands, including precise paintings of maps and eerie, post-apocalyptic semi-installations that are as carefully worked as any photorealist effort. His influence is deeply felt among artists working here, specifically in Timothy Harding’s illuminated assembled drawings, Jim Malone’s naturalist collages, and Christopher Blay’s wild sculptural tableaux.

One aspect of Fisher’s oeuvre, though, that probably keeps him out of the national conversation is nostalgia. In his solo show at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth a couple of years ago — the first Modern exhibit ever devoted to a Fort Worth artist — the pop culture references in Fisher’s pieces were jarringly stale: Mickey Mouse and King Kong haven’t aged well, evidently.

Observing In the Spirit of the Moment, North Texas artist Jerry Smith’s epic but intimate solo exhibit at the Fort Worth Community Arts Center, may induce an aha! moment: If an artist is going to traffic in topical references, this show reveals, he or she must choose his source material wisely.

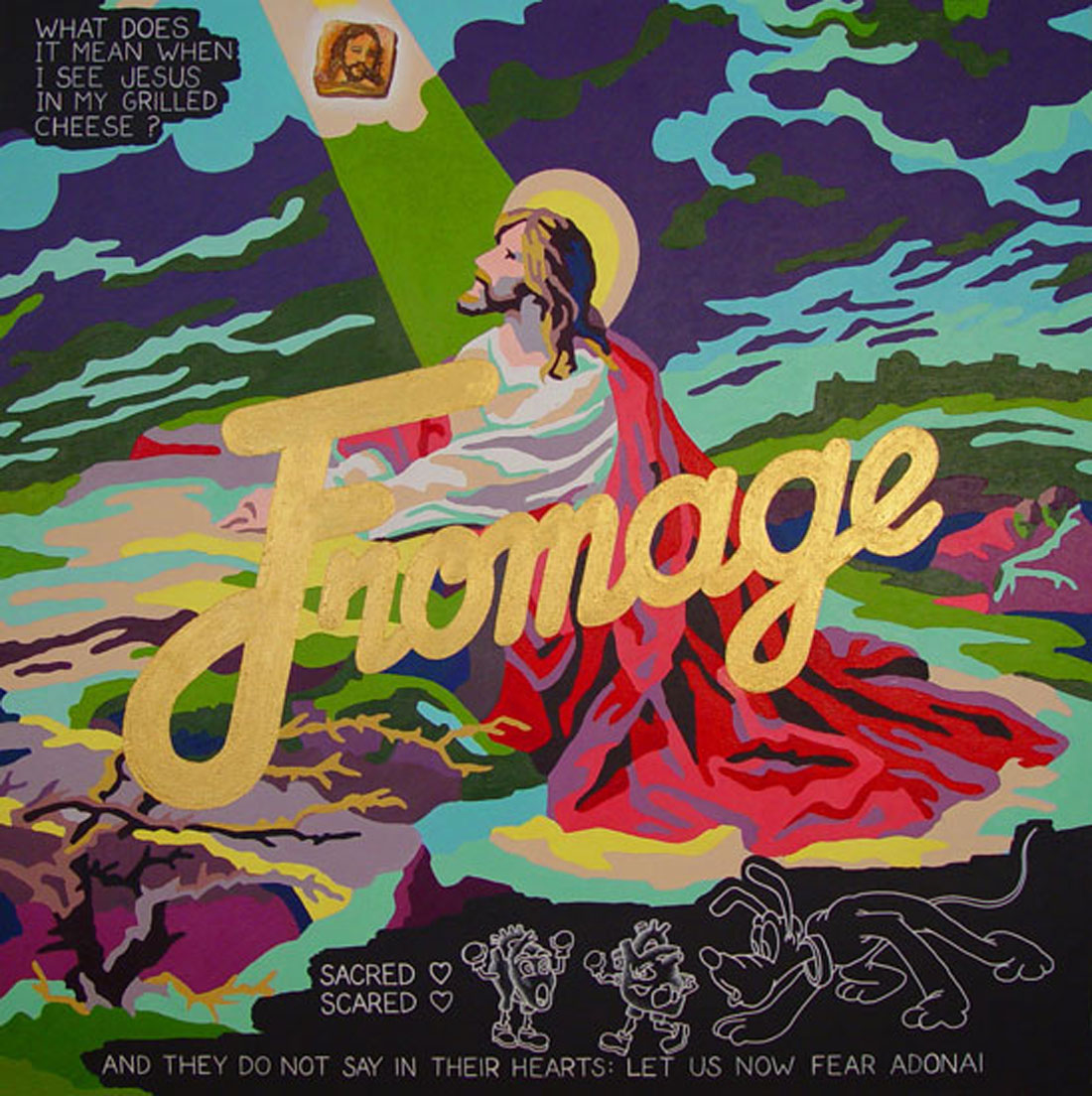

One pop-cult icon who may never go out of style is Euro-Jesus, the chestnut-haired, blue-eyed, bearded hippie with the fair complexion from classic Christian propaganda. This messianic ideal figures into a lot of Smith’s work but is neither debased nor glorified –– he’s just part of a visual language that Smith has cobbled together from advertising, cartoons, textbooks, religious iconography, and some unfortunately heavy-handed satire.

In “Cheesy Jesus No. 2,” Smith serves up a colorfully cartoonish version of Heinrich Hofmann’s famous 1890 imagining of the Garden of Gethsemane scene, in which Jesus, dressed in flowing robes, is kneeling on a rock with his hands folded in prayer within a stormy nighttime landscape. Smith violently shoves his painting into campy territory by making some mostly unwanted additions. You’ll wish he would have stopped at writing the word “Fromage” in cursive lettering across the middle of the canvas in gold paint marker. The other stuff –– cartoon characters at the bottom in white on black and a grilled cheese emblazoned with Jesus’ face floating above his head –– is all way too obvious and hamfisted. Smith even goes as far as to write, “What does it mean when I see Jesus in my grilled cheese?” in the upper left-hand corner. Sheesh, Jerry. Let it be, man. “Fromage” by itself would have been perfect and perfectly subversive, the start of a conversation between image and viewer, not an instruction manual for how he or she should think and feel.

“Cling” is another delightfully wrought and vibrant painting that’s done in by Smith’s over-the-top idea of humor. In front of a sky streaming with horizontal ribbons of red, black, brown, and gold, with a splotch of white, and a startled-looking longhorn dwarfing the silhouette of an oil derrick in the distance, Euro-Jesus holds a Bible in one hand and a glowing rifle in the other. “CLING” in gold scrolls across the bottom, and to the right are white-on-black drawings of muscles from an anatomy textbook. The one thing that elevates “Cling” above “Cheesy Jesus No. 2” is subtlety. The rifle doesn’t exactly jump out at you. It’s even somewhat inert after you recognize it, which ultimately makes the painting palatable, a little going a long way and all that.

Smith fares a bit better with the large acrylic piece “Shrouded & Veiled.” In jumbles of white lines that are nearly abstract, cowboys riding bucking broncos blend into a mushroom cloud across a distressed red-and-white pinstriped background. Across the bottom, Smith has written “SHROUDED & VEILED” in thin gold letters. In the upper left-hand corner is a black-and-white photo of a dreidel. Counterbalancing it in the lower right-hand corner is a colorful Euro-Jesus riding a red-and-gold bucking bronc. The fact that Smith only appears to be saying something but is biting his tongue makes for a tantalizing absurdity. Thank you. Finally.

Smith’s pure abstractions, in contrast, are superb. The found-object sculpture “Covered & Smothered” is a latticed dome made from large, thick wooden rulers; inside are store-bought salt containers haphazardly corralled and a vintage lamp. Directly on the carpeted floor, Smith has mounded 50 pounds of salt.

Smith’s other superlative found-object work is “Mammon.” It’s like Davy Jones’ wife’s vanity. The hanging, mostly black sculpture is framed by a ladder on the right, a ratty toboggan on the left, what looks like a flattened meteor above, and an askew black desk below. The piece is held together in the center by an upside-down wooden chair, a two-dimensional cutout of an old car, a portion of a wooden fence with a “For Sale” sign on it, and, on the desk, a plastic red lobster lamp and a plastic red pig in a tuxedo and top hat.

Like a symphony, “Mammon” and “Covered & Smothered” say a lot –– how in the hell Smith created a curved structure out of non-bending sticks is confounding –– but indirectly. You can feel that he’s saying something, that he’s sad here or that he’s happy there, but you can’t process it completely. This is what conceptual art is supposed to be. Vernon Fisher would be proud.

[box_info]

In the Spirit of the Moment

Thru Dec 20 at the Fort Worth Community Arts Center, 1300 Gendy St, FW. Free. 817-738-1938.

[/box_info]