Actor Ebony Marshall-Oliver was born and raised in a small south Louisiana town called Donaldsonville, although her family had moved to Atlanta by the time she was in high school. At 35, Marshall-Oliver is too young to have witnessed the major civil rights struggles that consumed the South in the 1950s and ’60s, but she does recall one ominous remnant of racial segregation that lingered in her hometown.

“When I was a little girl, there was a pool for white people and a pool for black people” in Donaldsonville, she said. “Even in the ’80s, they were still separate. I don’t recall that black people were officially told they couldn’t swim in the white pool, but you knew you weren’t supposed to. It was a given.”

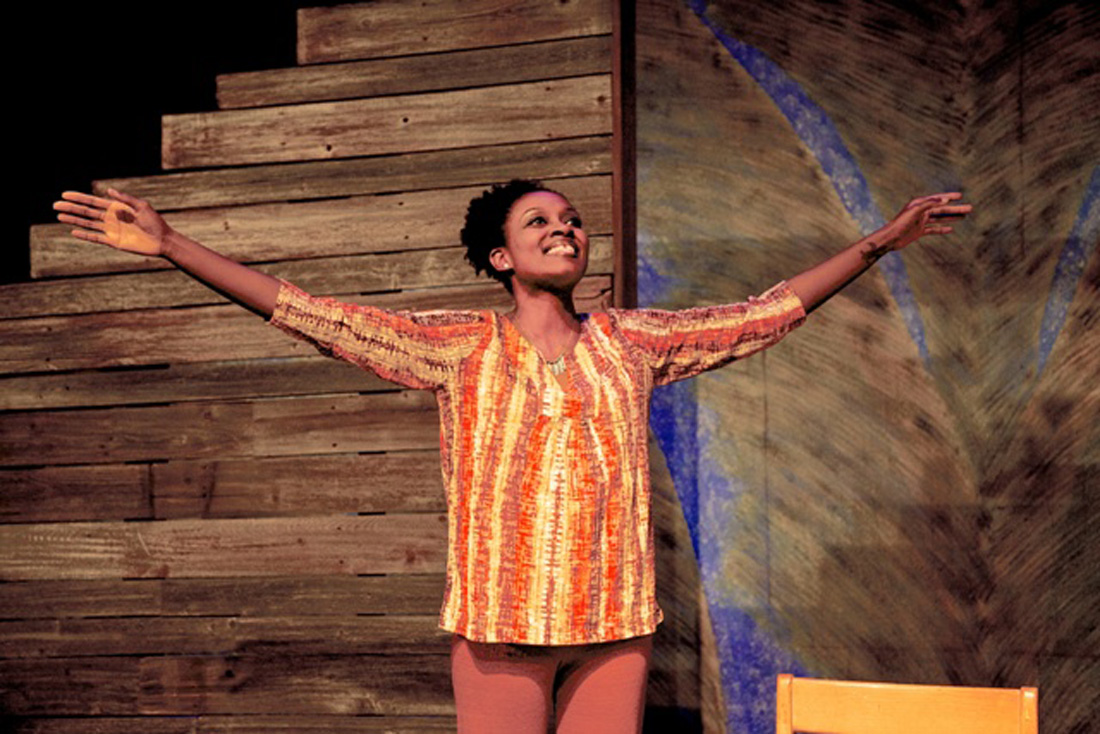

Marshall-Oliver has revisited a lot of her own memories, as well as those of her parents and grandparents, while rehearsing for the current one-woman show Neat at Jubilee Theatre. Written by actor and playwright Charlayne Woodard, the production is a sequel of sorts to Woodard’s similarly autobiographical Pretty Fire, which Marshall-Oliver performed last year at Jubilee to critical acclaim and sold-out houses. Both shows chronicle Woodard’s complex coming-of-age as an African-American woman in Albany, N.Y., and her experiences in Savannah, Ga., where as a child she visited family at the height of clashes over Jim Crow laws, school desegregation, and voting rights. Neat explores Woodard’s observations and experiences of race in both the North and the South, focusing on the 1960s and early ’70s when she was a teenager and a young adult. The show requires its star to play multiple characters of both genders and various ages, races, and social backgrounds.

Marshall-Oliver, who moved to Fort Worth in 2002 to work as a backup singer for gospel musician Gary Oliver (she later married his son), has seven or eight Jubilee shows under her belt but had never performed a one-woman show before Pretty Fire. Interestingly, Woodard herself refused to do another solo production for several years after that play became a huge hit –– she found the responsibility of carrying a whole show by herself too daunting. In contrast, Marshall-Oliver said that both Pretty Fire and Neat are particularly suited to her own strengths as a performer.

“From the [first] time I remember, I’ve always been a person who imitates other people,” she said. “Since I was a girl, people have thought I was naturally quiet and shy. I’m not. When I’m in a new environment, I sit back and observe. That helped me in developing these characters. … I had specific people from my own life that I used as models for the characters [in Woodard’s shows]. My own grandmother, my father, a friend of mine –– they all made it easier for me to find the physicalities of these people. And [Woodard’s] writing is so smart and easy to read and get into.”

Even more than Pretty Fire, Neat is bold in its assertion that racism has been a stain on the entire country, not just the South, where so many of the battles for equality played out in such ugly public episodes. Neat contains a particularly painful event from Woodard’s high school years in Albany: Along with some of her peers, she formed a black student alliance that asked the school district to use African-American history books already approved for the state universities. They scheduled a meeting with administrators in the school auditorium. The administrators didn’t show, but police in riot gear did. They busted down the doors and arrested several of the students. The local TV news broadcast in Albany later reported that police had quelled a riot among black high schoolers who were angry that “soul food” wasn’t being served in the cafeterias.

Given such outrageous and provocative anecdotes, is it difficult for Marshall-Oliver to maintain any kind of artistic distance from the material in Neat? Is it even desirable for an artist to keep a disciplined remove from someone else’s carefully composed memories and experiences? To put it more bluntly: As she performs the show night after night, how does Marshall-Oliver keep from getting really pissed off about some of the events that affected the playwright so personally?

“You have to have some kind of emotional investment,” in the piece, she said. “Otherwise the audience won’t believe what you’re saying. So, yes, there is a bit of how I personally feel about these situations. And it’s clear from the writing how [Woodard] felt about what happened. But you have to find a way to bring those elements together, to make it as authentic an experience as you can for the audience.”

[box_info]

Neat

Thru Nov 10 at Jubilee Theatre, 506 Main St, FW. $18-25. 817-338-4411.

[/box_info]