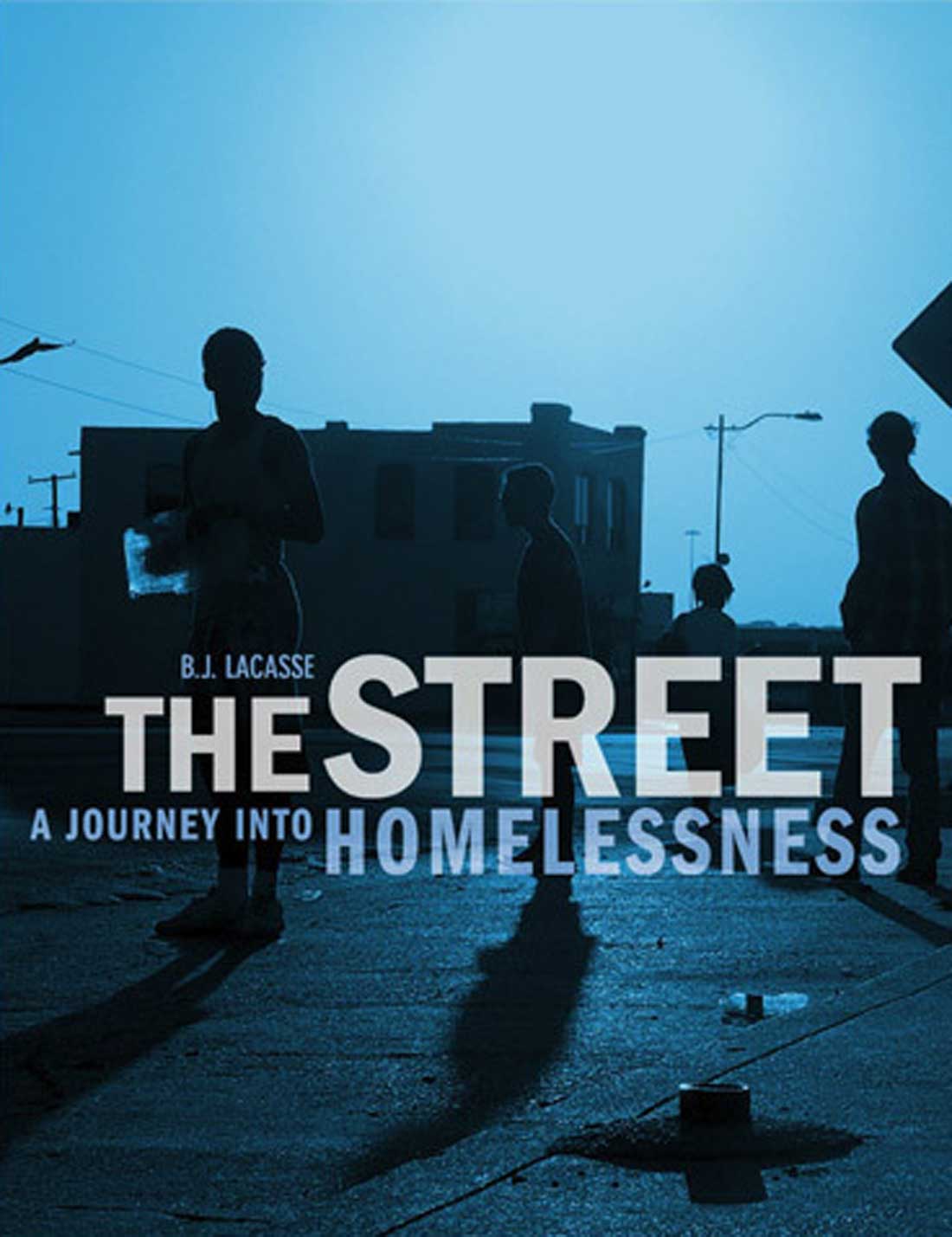

There’s absolutely nothing glamorous or sexy about documenting homelessness, and that’s the point of B.J. Lacasse’s new book, The Street: A Journey into Homelessness.

The Fort Worth photographer brings more than 30 years of experience to the book. Earlier projects — including Jon Bonnell’s cookbooks Fine Texas Cuisine and Texas Favorites — involved less serious topics. But those books and The Street both allowed Lacasse to document different sides of her favorite subject: Fort Worth.

The Streets grew out of an exhibit Lacasse was commissioned to create in honor of the 25th anniversary of the Presbyterian Night Shelter. The exhibit, which opened at the One Museum Place building on Fall Gallery Night 2009, proved so successful that it began touring the town, making stops at the Fort Worth Library’s central branch, a private school, and various churches. The first two-thirds of the book consists of photos from the exhibit, with most of the remaining third taken recently — one photo is from 1984.

Lacasse became involved in Fort Worth’s homeless population shortly after relocating to Fort Worth from Harrison, Pa., nearly 30 years ago. In the preface, she explains that she was out getting to know her new town by photographing it when she befriended a group of homeless people who seemed cheerful and willing to share their life stories while being photographed. But when she returned a few days later, one of the people, “Johnny,” was missing. She tracked him down at a detox complex known as “The Tank” as he was going through alcohol withdrawal and took what would be the last picture of him. He died a few days later.

Lacasse writes that she resolved then to tell his story and that of all of Fort Worth’s homeless. Johnny’s smiling picture illustrates the book’s opening chapter, “The Journey.”

Each page brings a new story of tragedy and hope. There is John, a middle-aged guy with a sociology degree who unexpectedly lost his job late in life and could no longer drive due to glaucoma. As John tells his story, it becomes obvious that he doesn’t fit the stereotype of homeless people as lazy, mentally ill drug addicts.

Then there’s Mike, a 43-year-old who spent most of his life in California and was an extra in the movie Wayne’s World. Health problems eventually destroyed both his marriage and his career. Despite his problems, Mike volunteers daily at PNS, the same homeless shelter that feeds him. He smiles as he talks about living longer than doctors predicted. Mike has advanced-stage leukemia.

The final chapter, “The Return,” depicts several encouraging stories of formerly homeless Fort Worth citizens who have turned their lives around with the help of public and private programs.

Lacasse gets dirty, delivering stomach-churning black-and-whites of gangrenous fingertips and of elderly folks sleeping on hot concrete, but she also offers stories of faith and hope. Through her writing, she drives home the point that these people are just that: people. As she carefully points out, each face belongs to someone’s father, mother, son, daughter, sister, or brother.

Lacasse’s expertise and numerous years behind the lens show clearly. Nearly all of her shots have depth of field, allowing us to see both the subjects and their all-important environment. And there is no sense of staging –– the images vary from panoramic shots of hidden tent cities to close-ups of defiant faces.

The Street fulfills Lacasse’s promise to tell Johnny’s story. It’s likely to have the added effect of changing some readers’ views on homelessness. Whether it does the latter or not, the book provides a portrait of Fort Worth’s homeless residents that is visceral, honest, and artful.