McCrary would graduate from TCU with a degree in business administration, but he found his calling elsewhere during his college years.

“I took a paid summer internship in Lubbock at a little bitty TV station,” he remembered. “Once the bug bit me, TV was all I wanted to do.” He learned the ropes first in Lubbock and then with the Texas music institution Austin City Limits, which was then in its infancy. Eventually, McCrary founded Clearwater Teleproductions, providing a mobile TV studio for broadcasting live events.

Operating from a base in Fort Worth, he worked a number of jobs but mainly as a technical director, sitting in a control room with a switcher and finding which cameras were giving the best angles.

He plied his trade at the 1984 Republican National Convention, multiple Cotton Bowl parades, and concerts by Harry Belafonte, Willie Nelson, and Ray Charles. Most of his experience, though, was with sports events: college football, college basketball, boxing, the Fort Worth Stock Show Rodeo, and the 1988 Winter Olympics opening ceremony.

“I produced and directed the college cheerleading and dance team championships for ESPN, of all things,” said McCrary.

McCrary married Johanna Reyna in 1974, and they had two sons. He declined to discuss his first marriage, which ended in 1996, saying only, “I got married very young. We weren’t a good fit.” He met Jaci (who had three sons of her own) after hiring her then-husband for a job in 1981. The two couples remained friends for more than a decade.

In 1988 a project for Texas Tech University’s medical school took him back to Lubbock. The school needed to communicate with doctors in charge of delivering healthcare in almost half of Texas’ landmass. The challenge of making it possible for those doctors to talk with one another was formidable.

“Can we build a network where doctors in remote areas can consult with doctors in Lubbock, Amarillo, El Paso, Odessa, and Midland?” McCrary said of his project back then. “Now it’s all Skype, but when I started this, it hadn’t happened.” He spent five years building and maintaining a video network for the school, allowing classes to be taught remotely and even letting doctors remotely observe operating room procedures.

After her marriage dissolved in 1993, Jaci found her own way to Lubbock, enrolling in Tech’s Ph.D. program for counseling education. “[Giles] was the only person I knew out there,” she said. “He taught me to use a computer.”

They didn’t start dating until his marriage ended three years later. “I was afraid to date him, because we had been friends for such a long time.”

Though the video project eventually lost its funding, Giles stayed in West Texas to work at the investment firm owned and operated by his father and sister. “I felt I should learn the family business,” he said. “It wasn’t my cup of tea. I was pushing pieces of paper from one side of my desk to the other.”

Describing himself as “bored to death” in Lubbock, McCrary also earned a master’s degree in the same program as Jaci’s. In the process, he picked up a skill that would prove more germane to his future vocation as a documentarian. “That’s where I learned interviewing,” he said.

After getting married in 1998, the couple resolved to return to Fort Worth, where they had both spent so much of their lives. In the meantime, Giles put his skills to work compiling video tributes for friends and relatives. He also received funding from General Mills to make a documentary about the city of Post in 2001.

Through his work, he had seen others using visuals to tell a story. “I had watched news editors at work,” he said. “So much of storytelling is just logic. It’s all about being empathic and understanding how things flow.”

The couple finally made the move back to Fort Worth in 2007, with Giles in semi-retirement and Jaci initially teaching at Tarleton State University before going into private practice as a counselor.

“I didn’t have any particular plans,” Giles said — until his wife introduced him to some old friends.

********

“We went to a Cellar reunion in 2009,” said Jaci. She had kept in touch with friends and acquaintances from the club through a listserv. “Everybody knew me, and I introduced Giles to them.” When someone floated the idea of making a documentary film about the club, Jaci spoke up.

“I volunteer him for things all the time,” she said. “I was interested in the bond these people had. What made these people stick together?”

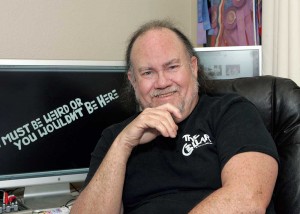

“My wife was right,” said Giles, who started to get to know the musicians, often by playing guitar with them. “Like any network, you meet new people, and it grows and grows.” He already had cameras and equipment from his work on the Post documentary, so he set up a green screen in a bedroom at his house and invited people to sit down for interviews.

The couple approached the documentary like a research project, with Jaci helping design a list of questions to ask all the interview subjects.

“We decided early on that the history of the joint was just one aspect of the whole story,” said Giles. “We are both fascinated with human development, so we formed some questions that would give us insight into how the Cellar affected the development of these people during their late teens and early 20s.”

“There had been nothing previously researched regarding the full impact of clubs such as this on people’s lives,” Jaci elaborated. “We felt that qualitative research was the most appropriate method to use.”

The questions were open-ended, and people were encouraged to reminisce. “Sometimes I would just say, ‘Pat Kirkwood,’ and let people talk. It was like word association. I didn’t want to taint the process,” said Giles.

The subjects’ responses were then subjected to rigorous verification, an important process when so many people were telling stories. “You transcribe what people say and code it, and if three or four people say the same thing, you have a good chance that it’s true,” he said.

The rather scholarly method did more than provide a way to verify stories. It also helped bring order to his storytelling. McCrary keeps a detailed database with interview fragments keyed to different sections. “If I want to find out about bouncers, I go to the section on bouncers, and it has everything that everybody said.”

Jaci provided more than just scholarly support. “I was curious to find out how the place affected women,” she said, noting that the place was chauvinistic in many ways, despite the degree of protection afforded by the bouncers. “A lot of the women we caught up with had mixed and even negative feelings about the Cellar.”

Sadly, none of the women interviewed were willing to discuss their painful experiences on camera. Jaci said all the interview subjects remained loyal to the Cellar, but she wished she had been able to talk to more women.

The green screen allows McCrary to add old photos behind the subjects when he transfers the interviews to film. He has hundreds of photos from the Cellar’s heyday, and the technique helps take the place of film or audio footage from the Cellar, very little of which exists.

“Most portable cameras didn’t have sound back then, and no one was rolling tape in [the Cellar],” explained Nobles, comparing McCrary’s situation to his own film about teen bands.

“There’s more record of those teen bands because there was more of a commercial market for their music, even though the Cellar guys were ahead of them musically. Pat Kirkwood just wanted the music there to get people into the club. He wasn’t interested in exporting the music to other platforms.”

McCrary has put together 41 minutes of a finished work that he estimates will run between 80 and 90 minutes. He figured that it took him three working hours to turn out each minute of polished footage.

“He’s a perfectionist,” said Nobles. “He’ll work it and rework it until he gets it right.”

That attitude served McCrary well last October, when a mysterious system failure caused him to lose a large chunk of edited footage in the middle of his film. “Somehow the program files became corrupted,” he said. “I had three backups, and it rippled through all the backups.”

He spent several months talking to engineers at Apple, going to the very top of the hierarchy, but none of the experts could ever figure out precisely what had gone wrong. McCrary compared it to a reporter losing a nearly finished story, assuming that said reporter had spent years working on an article.

“A lot of people would have put a gun to their heads,” said Nobles. “But Giles is one of the calmest, nicest guys I know. When he got into rebuilding it, he got excited. It made him re-evaluate things, and the movie’s brighter and quicker now.”

In re-creating the ruined segments, McCrary had the benefit of his own extensive notes, as well as a DVD from a work-in-progress version of the film that he had screened at the Fort Worth Public Library in 2010. “I don’t throw fits,” he said. “Eventually, I came to look at it as a good thing.”

McCrary wants to finish You Must Be Weird by June 14, the deadline for submission to the Lone Star International Film Festival. Ultimately, it has been a labor of love.

“Giles isn’t looking to get his movie played on HBO and seen by millions of people,” said Nobles. “He loves the people who created this music. These musicians worked for decades, and they didn’t have much to show for it except their stories. He wants to capture these stories and make sure they don’t die with the people who lived them. This movie is really just a way of saying thank you.”

“We’re hoping to win awards with this,” said Jaci. “This film is about so much more than just this one place at one time. This is about Fort Worth, about our history.”

Most infamous of the “must go to places” in Ft. Worth for Texas teen youth in the ’60’s. Thousands of youthful farmers, rancher/stockmen attending the annual “Fort Worth Fat Stock Show”. Right of passage for a lot of those FFA kids, never got to go myself, but listened to all their stories. Now we know, McCormicks—very cool. Thank you Giles and Jaci, I ALWAYS wanted to go. L.O., PHS ’65

I was a Cellar Dweller at the original Cellar that was under where the convention center now stands. I literally lived at the Cellar for eight months during it’s first year in business. I worked for Kirkwood as a musician for four years off and on and probably know him and the Cellar’s early history better than anyone now alive.

Jack Remington

Man, how I would love to buy you dinner and hear some of those stories. We spent many a late night at the Dallas Cellar, right across from the “ABSOLUTELY NO PARKING!!” flashing sign at KLIF radio.

I worked at the cellar in the late 60’s and Pat’s other business at the time the Benbrook marina. I have many fond memories of those days.

The CELLAR was ahead of it’s time as a counter culture club. Looks like the perfect place to conduct a teenage version of the MKULTRA “Midnight Climax” operation. Did you come across anything about or connections between: Jack Ruby? Lee Harvey Oswald? The movie Naughty Dallas? How much cooperation did Pat Kirkwood get from the authorities? The backgrounds of his bouncers? The Secret Service Agents partying into the morning the day JFK was assassinated? Some have posed the idea that the whole “Hippie” phenomenon in the 60’s was a government sponsored psychological warfare operation. So hip and kool, yet no blacks and bouncers that would have fit in at Jack Ruby’s Carousel Club. Jack Ruby boasted connections at Reprise Records. J.D. Tippit was in Top Ten Records in Dallas minutes before he was murdered. EVIL spelled backwards is LIVE?

I went there for a while and started when I was 17. My brother was a bouncer there so I was a regular. I really miss those times. Great music and I made friends with the waitresses and one night went to Johnny Carroll’s house that night.

I did get drinks and was even a bouncer when Candy Barr came there. I remember Jimmy and Norm. I went to Pat’s house once with my brother. On the 4th of July I think is when we had the artist and models ball and at 5 in the morning went to Lake Worth to have fun on goat island. The vinison was really good. I miss the bands and the people and the gentleman who ran the kitchen. I even made drinks one night.

Does anyone know my big sister Pam Hawkins / Flower she was a waitress at The Cellar? She was a tall thin blonde with the best smile. She pasted when I was only 15 so i would love to hear your memories of her and photos if you have them.

My name is Mike. My brother Dave and I were Cellar Dwellers back in the early 60s. We were both Artists at the Cellar. Dave drew portraits of the Cellar dwellers as they sat and enjoyed the music. He also painted the epic 6 foot high FINGER that was behind the bandstand in the original Cellar. When the Cellar relocated a few blocks up the street, I painted all of the wording and graphics on the walls of that upstairs Cellar. I painted the 3 faces on the large wall opposite the bandstand and I also painted another rendition of the famous FINGER behind the bandstand. I painted the stairway scene that appeared just inside the glass door entrance to the upstairs Fort Worth Cellar. I was also responsible for painting all the lettering and graphics at the new Dallas and Houston Cellar locations. Each had the 3 faces and the Dayglow FINGER adorning the walls.

As everyone said above, the Cellar was the happening place, and most everybody in their 20s and 30s went there. I remember several of the Cellar personalities including Pat Kirkwood (Owner), Jimmie Hill (Manager), Johnny Carrol. Jack Estes, King Cannibal Jones, Jo-Jo (bouncer), Uncle Leo, Dub, Charlie, just to name a few of the regulars.

I have some photos taken of me and some of the paintings I did at all 3 Cellars. One includes a good friend of mine Pat Pridgeon as I was painting the FINGER in Houston. If I knew where to post them online, I would be happy to add them to some of the other nostalgic memorabilia pertaining to the Cellar.

I worked at the orginal Cellar the summer of 1962 as the portrait artist. I was “li’l Dave”. It was quite the place to hang out. I developed my love of folk music listening to Jack Estes’ singing. I recall Pat Kirkwood would sometimes be seen to be packing a shiny chrome .45 automatic. I painted the “finger” on the wall behind the bandstand. I got to witness a few undesirables get “escorted” out and up the stairs while I was there. It was a loose place but there were limits to what you could do down there. I have fond memories of the place.

I went to the Cellar a few times as youngster in the early 60s. It was downstairs at that time. As I recall everything was painted black. walls, ceiling, floor. Very dark place with only the paintings on the walls and writings in glow in the dark paint. The only two sayings that I really remember painted on the wall were “You must be weird or you wouldn’t be here” and “EVIL spelled backwards is LIVE !”. Sat on pillows on the floor with coffee tables to set our drinks and ashtray on. Waitresses dressed only in panties and bra served drinks. But as I recall….we usually brought in our own beer or liquor in a paper bag. Great music ….the one I remember most was “CC Rider”. Was a very rough looking place but I never had any trouble there. Perhaps that was because one of my friends who went there often was as tough as any bouncer. He was from Cleburne. Most knew him as “Bulldog”. It was a fun adventure as a kid in the 60s……..ahhhh but that was then…………. no more for me.

I worked at the Ft Worth Cellar from 65-67.It was upstairs. I was a waitress and dancing girl. I am the owner of the Group-Texas Cellars.

I was 17 in 1965 when I first started coming to the Cellar. I was in high school in Dallas but I had my own car and drove to the Cellar constantly. It was my second home. I remember how friendly Pat Kirkwood was to me and I actually went to his house for coffee at 6:00 am after sitting in the Cellar all night. I told my parents I was spending the night with a friend. And I got away with it

Everyone was friendly and I got to know most of the waitresses. I came to listen to some of the best music ever. These young musicians played their hearts out. The Cellar kept me sane during my teen years.

Shelley McBride here.

I played at the Dallas Cellar when I was 18 in

1968. I remember going first to the Ft Worth Cellar driving 125 miles from Durant Oklahoma to see Bugs Henderson as well as the Cellar Dwellers. Bugs was a big inspiration to my guitar work and the Dwellers were spot on with the Beatles tunes. In Dallas, we played across from KLIF downtown.

I was 17-18ish but finally reached my goal of being good enough to play there with a respectable Allmans Brothers copy band. Mike Ryner was the drummer, Anthony Brogden was a guitarist, and I played guitar and was the lead vocalist. I remember Stevie Ray stopping by and sitting in as well as Nitzinger and Freddie King. A guitarist named Anthony Polusa who later played with the Carpenters had a band called the Abstracts. He was awesome. Big John O’Daniels would stop in and sing his ass off. It was the place that defined the men from the boys as musicians.I still play but the caliber of musicians back then was serious. The dancing girls were always unique from any other club. The manager there was Johnny Carrol and a small biker named Elf. Those moments are indelible and the music played there was powerful. Our band was Street Noise. Unfortunately “everyone I thought was cool is six feet underground”…Johnny Winter! Thanks for keeping this iconic place alive. Shelley McBride,Denison, Texas.

Thanks for the great anecdotes and memories from the cellar dwellers. Those were strange times. Not like today when everyone wants tries to project weirdness. In those days you had to have guts to walk on the wild side.