Larry Tubb doesn’t remember knowing a single kid who had asthma when he was growing up. As a Scout leader 20 years later, he knew of only one troop member who dealt with the breathing disorder.

“Now 20 percent of the population suffers from it,” Tubb said, and gathering information about the disease’s effects in North Texas is one of his major concerns, as senior vice president for planning with the Cook Children’s health system.

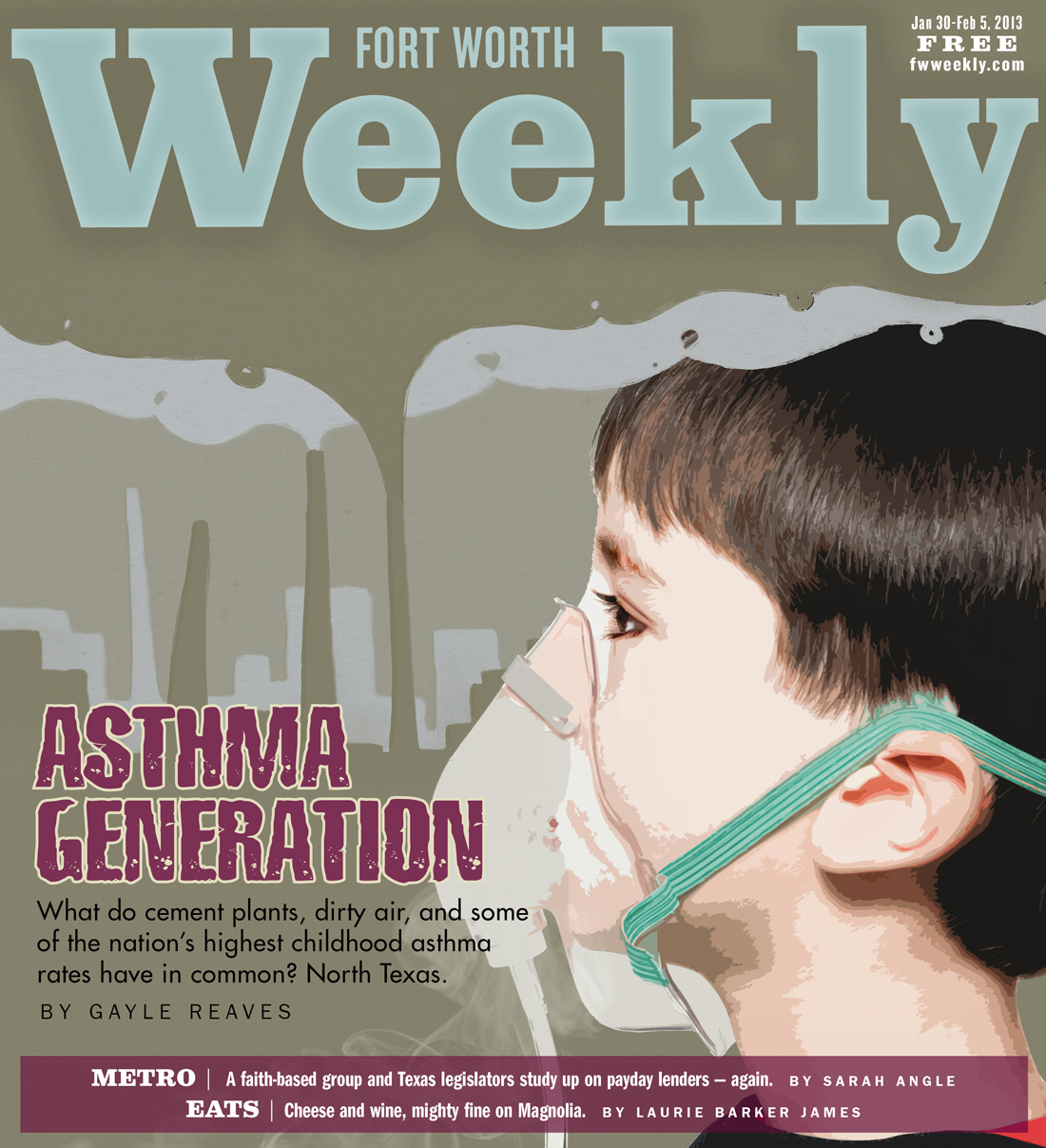

Today asthma is the number-one children’s health issue in this part of Texas, and while the science still isn’t there to pin down its causes, evidence is growing that the cement plants and other heavy industry in Ellis County, along with traffic, gas drilling, and other air pollution sources across the region, are making the problem worse.

In 2009, a groundbreaking community-wide health assessment study by Cook Children’s revealed that kids in a six-county area surrounding Fort Worth were being diagnosed with asthma at rates as high as 25 percent of their age group. Newer data gathered by Cook last year showed changes in some counties and some groups, but overall asthma rates here still far outstrip state and national averages. Asthma remains the leading cause of children’s visits to emergency rooms and a major contributor to their absences from school.

Last fall, an article by researchers from the University of Texas at Arlington, based on the original Cook survey, noted that the data “showed that the bulk of Tarrant County asthma cases lie directly in the path of southeasterly winds that have historically carried high levels of particulate matter from working cement kilns” near Midlothian. Asthma prevalence, the UTA researchers said, “increases in a linear configuration within the path of this ‘cement plume.’ ”

Then in November, an agency that works with the Centers for Disease Control reported that monitoring data show that certain categories of emissions from the cement and steel plants in the Midlothian area have been heavy enough to harm some people’s health, in the past and in some cases continuing into the present.

The report from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry also carried messages for Texas’ environmental regulators, recommending that they do more monitoring of air pollution exposures downwind of Midlothian and take action to reduce emissions of certain substances.

“For the first time, a federal agency known to avoid coming to any conclusion about anything was forced to say that human health was adversely affected by the operations of industry in Midlothian,” said a release from Downwinders at Risk, a group that has been central to the fight against North Texas air pollution.

All of which left environmentalists shaking their heads over the Environmental Protection Agency’s decision late last month to delay by two more years the tougher rules that were to have gone into effect this year, requiring cement plant operators to reduce emissions of mercury and other pollutants.

“The frustrating part about that whole process is, nobody at EPA can tell us why they did it,” said Jim Schermbeck of Downwinders. The decision was especially mystifying because many companies have already purchased the equipment they’d need to bring them into compliance with the stricter rules, he said. “Nobody can get a straight answer.”

********

Sal and Grace Mier of Midlothian have worked for nine years to get the ATSDR evaluation of air pollution in Midlothian. They live just outside the city limits and about a mile and a half east of the Holcim cement complex.

“We’re senior citizens, and this has been a big challenge,” said Sal Mier, who retired in 1994 as regional director of the CDC in the Dallas area. “This is not a very popular thing to be doing in our community,” where the cement industry provides so many jobs and public benefits, he said. Because of that, he said, they never joined Downwinders or any other group that might influence them or be perceived as influencing them.

“Our goal has never been to shut down the industries,” he said. “We wanted to make sure we had the healthiest environment possible for our young grandchildren and children yet to be born, and when we looked at the data, we were concerned.” He and his wife worry about upper respiratory diseases as well as birth defects that could be caused by air pollution.

After the Miers requested the study from ATSDR, they were told, initially, that the federal agency had subcontracted the Midlothian study to the state health department.

“We never felt like we could get an objective view of our situation from the people who had been looking at it year after year after year,” Mier said — people who were basing their evaluations on data from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, an agency that is widely viewed by environmentalists and many public officials as being soft on polluters.

Mier went to Washington, D.C., to testify before a House subcommittee about the problem. After that, he said, ATSDR assigned the study instead to its own scientists. “When that decision was made, I felt much better,” he said. “We wanted the best job done.”

The ATSDR report was based on a review of air samples and monitoring. The researchers concluded that, based on classes of pollutants covered by the Clean Air Act — including ozone, particulate matter, lead, and sulfur dioxide — the Midlothian industries could indeed have harmed the health of area residents. In some cases, the agency said, only those already sensitive to air quality conditions, such as asthma sufferers, would have been affected. In other cases, the harmful effects could have extended to all children living in certain areas or all the residents of specific neighborhoods.

Ozone levels could still be harming “active children and adults” and those with respiratory diseases, the report said.

In some cases, the ATSDR review found that pollution levels around the Midlothian plants are or have been some of the worst in the state. One area north of the TXI cement plant had some of the highest sulfur dioxide concentrations in the state between 1999 and 2001, the report said. In the mid-1990s, lead levels just north of the Gerdau Ameristeel plant were among the highest lead concentrations recorded in the state and “could have harmed the health of children who resided or frequently played in the area,” researchers found.

The ATSDR scientists also made numerous recommendations to TCEQ about reducing sulfur dioxide and particulate matter emissions and ozone exposure. The federal agency report also concluded that TCEQ needs to do more monitoring. In particular, the scientists said, there is a “lack of monitoring data for residential neighborhoods in immediate proximity” to the cement plants and steel plant.

TCEQ officials did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Mier explained that the November report was the first of several that the ATSDR plans to release over the next year and a half. Other reports, he said, will cover emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), heavy metals, and kiln dust; evaluate water and soil conditions; and evaluate the effects of all the pollution on the health of animals and human beings in the area.

“I keep being told this is a monster of a project,” he said. “I feel good that they’re looking at it much more comprehensively and objectively than in the past.”

********

I found this article just as I’m getting ready to go pick up my son’s nebulizer refill. Thank you for not letting up on polluters.