In an odd coincidence, both Gordon and Walters relocated around the same time to Houston and could no longer commit full time to Holy Moly. Bassist Hull, a veteran scenester and musician, quickly hopped onboard, and the band performed for a while as a percussion-less trio. An accumulation of new material pushed Rose and company back into the studio, once again with Hunt.

Hull holds the thirtysomething producer in high esteem, saying that he’s “good to work with whether you’re trying to execute or be in creative headspace. … [Hunt is] real good about being OCD enough to run the console but also being in touch with other side of it” to identify good takes or passages.

Hunt got to know Weaver and Rose by going to a lot of Aardvark shows. One night, the co-songwriters asked him to collaborate. “At first, it just seemed like a fun project to be a part of,” Hunt said, adding that he’d never made a record like the one Weaver and Rose were describing and welcomed the challenge. But once tape began to roll, Hunt realized that the Holy Moly sound wasn’t all just “party good-time craziness, although it is every bit of that,” he said. The music was also “well crafted, well executed, full of conviction, and innovative.”

Walters agreed to play drums on the record but had to pull out at the last minute. Hull’s drummer friend Carpenter, who had been looking for session work, happily filled in.

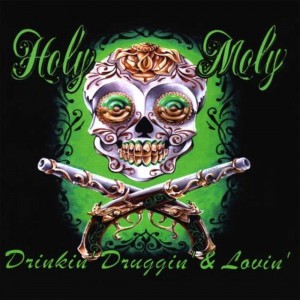

Drinkin’, Druggin’, & Lovin’, featuring the showstopper “Holy Moly Show” and Rose’s tribute to his mother, “Rebecca Lynn,” came out and was promptly voted Album of the Year in the 2009 Fort Worth Weekly Music Awards. In the spring, the band was contacted by a European promoter, offering a deal that sounded so over the top that Weaver began a mini-investigation. He contacted several bands that had worked with the promoter to make sure he was legit.

The Holy Moly guys said their month-long Euro-tour in June 2009 was like a fantasy. They stayed in comfy houses, woke up every morning to massive breakfasts, rehearsed or wrote during the afternoons, sat down to massive meals and beers before shows, and played just about every night to enthusiastic crowds throughout Northern Europe. All the band was responsible for financially was airfare. The guys actually made money on the trip.

During those fat, contented European afternoons, Holy Moly got a lot of writing done. A couple of weeks after returning home, the boys piled into Fort Worth Sound with Hunt to begin recording their third album, Clickity Clack. On Oct. 14, 2009, HearSay wrote, “Most of the songs are uptempo shuffles, skipping happily and giddily — and somewhat drunkenly — over Rose’s charming, often hilarious tales of growing up tough, growing old with the bottle, and relationships gone wrong — or right.”

After the album came out, the band packed up and went back on tour, this time in-country, playing cities and towns from Fort Worth to St. Louis to New York City and back and opening for heavy-hitters like The Defibrillators and Unknown Hinson. In between gigs, Rose was busting his hump at the salon.

Rose and Weaver never stopped writing, though, and their prolific output led them back into the studio with Hunt, who had closed his Dallas location and was officing in Oklahoma City at Blackwatch Studios.

Shortly before the European tour, Rose married his longtime girlfriend, Jeni. But success with his music also translated to problems at home, and the couple split after about five years.

Only a couple of weeks after the breakup, Rose met an employee at The Aardvark. Hannah Freudiger would change his life more than any record or tour.

********

Rose and Hannah became a couple in the fall of 2010. Not long after, she announced that she was pregnant. The happiness, though, soon gave way to strife and confusion. “I was still trying to figure out how to communicate in a relationship, where I could talk to a person and say anything, and she was just going to listen and fight back,” Rose said. “Not lead me. But fight back. It was hard. It was tough.”

Adding to the pressure, Hannah was not thrilled to see her husband driving 200 miles north to make music when she was only two weeks from her due date.

The closer she got to her due date, the more relaxed the couple became. The day Rose drove his wife to the hospital to have the baby was perfect, he recalled. “We were smiling at each other,” Rose remembered. “We just couldn’t take our eyes off each other. … We were just so confident about life at that point. Nothing could break us.”

The nurse began working the heart monitors. She soon noticed something abnormal. “Now that morning, my wife felt the kid moving,” Rose said. “I remember laying there the night before, my arm wrapped around her, feeling the kid moving around.”

The nurse got a strange look on her face, which alarmed but didn’t necessarily worry Rose. Hannah was still blissful.

The nurse fetched a new monitor, but the result was the same. A sonogram machine was brought in. Hannah still had no idea what was going on. “I see [the technician] focus in something, and I see her type the word ‘heart’ over something,” Rose recalled. “It wasn’t moving. And I knew at that moment that [my daughter] was dead, that she was gone.”

The tech completed the test a few minutes later. “My wife’s still staring at me,” Rose recalled. “I’m sitting there, ‘How in the hell am I going to tell her our daughter’s dead?’ ”

The tech stopped and began unplugging cords and without a word rolled the machine out of the room. “My wife looks at me,” Rose said. “I’m just holding her hand, squeezing it as hard as I can. She looks at me. She looks over at the nurse, and the nurse goes, ‘I’m so sorry.’ ”

The delivery was performed a couple hours later. “I never knew anybody who could be as strong as [Hannah] was at that time,” Rose said. “It was heart-wrenching. … We didn’t know what to do. We were in total shock.”

The doctors handed Scarlet to her parents. “She was huge,” Rose said. “Over eight pounds. She was so pretty. Bright, bright blue eyes. Light blonde hair.”

The nurses took the baby away, cleaned her up, and returned her to her parents, who loved on her until the time came to give her back. “We had to go through losing her again,” Rose said.

Rose put his grief aside to care for his wife and Ede Faye. “To actually take some of your coping strength from 3-year-old seems really insane, but we did,” Rose said. “It makes you want to be stronger, and because she couldn’t understand what happened, it made me be stronger as well.”

********

The return to reality was harsh but ultimately therapeutic, Rose said. “I’ve got 400-something [salon] clients, and every single person who sits in my chair was, like, ‘So where’s the baby pictures?’ … I told the story so many times, I think it helped me.”

Two weeks after Scarlet died, Rose recorded “Weird Kid,” a melancholy solo-acoustic song and the next-to-last track on the album. At producer Hunt’s house in Fort Worth, Rose sat in a room with only his acoustic guitar and a microphone. “I played the song three times, and that was it,” Rose said. “That’s all I could do. I was done, so emotionally confused, empty and filled at the same time.”

The album marked a change, in both the band and Rose. Unlike the previous three albums, Grasshopper Cowpunk has range and is “littered with superb examples of C&W-inflected songsmithery,” HearSay wrote on Oct. 5, 2011. Soft spots and detonations of fury intermingle. The best track might be the first. “Saturday Night” pivots on some deft time-signature changes and is driven by the chorus, in which Rose holds a note seemingly forever as the guitars and drums swirl and thunder beneath him.

“That album was what it was supposed to be, that was me getting to express a little bit more,” Rose said. “I realized I didn’t have to be so ‘fuck you.’ … It didn’t have to be three power chords and some handclaps. It could be a little more.”

Rose and Hannah’s ordeal has become a focal point of Rose’s songwriting. One of his new songs is “I’ll Linger on This for a Little While”:

On my daughter’s birthday, I woke up with a smile.

I know it’s hard to imagine, but my smile actually measured a mile.

My beautiful wife so full of life is about to give me a child.

And that’s one of those moments I chose to linger on for a little while.

Life will learn you a lesson. It teaches you every day. You can’t have the good times without the bad times. It’s a lesson I learned in one day.

On my daughter’s birthday, it ended in a river of tears.

I know it’s hard to imagine, but our sorrow would last for some years,

and at the end of that day I really couldn’t say if I’d ever be happy again.

But look at us now. We’ve made it somehow.

My wife is still my best friend, and I’ll linger on that to the end.

The baby’s death and its emotional and psychological reverberations have allowed Rose to “play songs with emotion and not have to fake it with intensity,” he said.

********

Rose and Hannah married this March and began trying to get pregnant again. Rose said their honeymoon, in Arkansas, was great but also melancholy –– before leaving, he had learned that Hannah’s sister, who had become pregnant a second time, had lost her child.

Near the one-year anniversary of Scarlet’s death, Rose and Hannah became pregnant with Brazos “not as a replacement,” Rose said, “just to further this dream that we’ve committed to.”

Rose has been invigorated by the pregnancy. “The way I was with life, not caring about anything, was wrong,” he said. “You should care about every single person, every single thing in your life. [The pregnancy] really put what was important right there in my face.”

Rose’s attitude toward Holy Moly has also changed. He now cares what he sounds like. “I was so punk, I’d get up there onstage and say, ‘Check, check. It’s good. Let’s go.’ I didn’t care about anything,” he said. “Now when I get up there, I’m not gonna stop until it sounds good, because I realize that every person who steps into that building is spending their life with me.”

Losing a child, he said, has also affected him musically. It “makes the impossible seem possible. … You realize how important every single fucking second of life is. … I’m so grateful to be able to stand up there and connect with a large group of people at once.”

Music keeps saving Rose’s life. “If I hadn’t found music in the last couple years, I don’t know who I’d be,” he said.

Anyone who’s seen Holy Moly live knows that, while there are contemplative, truly musical moments, the majority of the show is about barreling headlong into bacchanalia. While Rose is definitely the star, the rhythm section is also pretty wheels-off. Carpenter pounds the living life out of his skins but also conjures up odd polyrhythms that somehow complement the three-chords-and-a-cloud-of-dust riffage, and the nerdy Hull is a monster onstage, punching, pulling, and slapping his upright and jumping all around like some sort of bespectacled Tarzan. There’s simply no denying the pure joy manifest onstage.

********

Just a couple of days ago, Rose performed a song he had learned via request, Amos Lee’s “Sweet Pea,” at the funeral for the infant daughter of two of his friends. “I could not have done that if [Hannah] had been there,” Rose said. “If I’d even see her shed one tear, my immediate reaction would have been to put that guitar down and walk over there and hug her and take care of her.”

The trauma he and his wife have suffered is the reason that Rose may perform or record only a fraction of the songs he’s written about their dead daughter. And the band intends to hit the studio soon, perhaps as early as this spring, once again with Hunt. “I’m convinced we have yet to hear the best of Holy Moly,” Hunt said. “It just keeps getting better.”

(And once again, the amazing Día de Los Muertos-influenced artwork –– lots of skulls, guns, and flowers –– will be done by famed local tattoo artist Troll.)

Like Rose’s life now, full of highs and lows, Holy Moly’s next album won’t be all about drinkin’, druggin’, and lovin’. “There’ll be some sweetness and sincerity too,” he said. “And some anger.”

Rose’s father, an overweight smoker and drinker battling multiple illnesses, still lives in Arlington with his parents, in a little apartment behind the house. Rose made peace with his old man not long after the overdose.

“It put a lot of things in perspective,” Rose said. “You reach a certain point when you’ve got to stop blaming your parents or anything in life … . You’ve got to start taking responsibility. If my life sucks, it’s my fault. … I razzed him a little bit about the things he did to me as a kid and a young adult, and I went, ‘You know what? I forgive you. We’re 100 percent on equal footing.’

“If I die tomorrow or live another 80 years, I’ll never stop living,” Rose continued. “I’ll never stop driving. I’ll never stop loving my wife. I’ll never stop playing.”

Excellent story! Very informative and well-written.

Thank you, Stacey.