This month is the 50th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, so we may hear a great deal about the weeks when the world almost died. But the past is a foreign country, a place where everything was in black-and-white and men still wore hats, so it’s just scary stories about a long-gone time. Or so it seems.

The outlines of the tale are familiar. It was 17 years since the United States had used nuclear weapons on Japan, and the Soviet Union now had them too. Lots of them: American and Soviet arsenals included some 30,000 nuclear weapons, and not all of them were carried by bombers anymore. Some were mounted on rockets that could reach their targets in the other country in half an hour. There couldn’t be a more hair-trigger situation than that, you might think — but then things got a lot worse.

At the start of the 1960s, Moscow gained a new Communist ally in Fidel Castro, but the United States kept talking about invading Cuba. So Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev moved some nuclear-tipped missiles to Cuba to deter the U.S. from attacking the island. However, in Cuba the Soviet missiles would be only five minutes away from American targets. That caused panic in Washington.

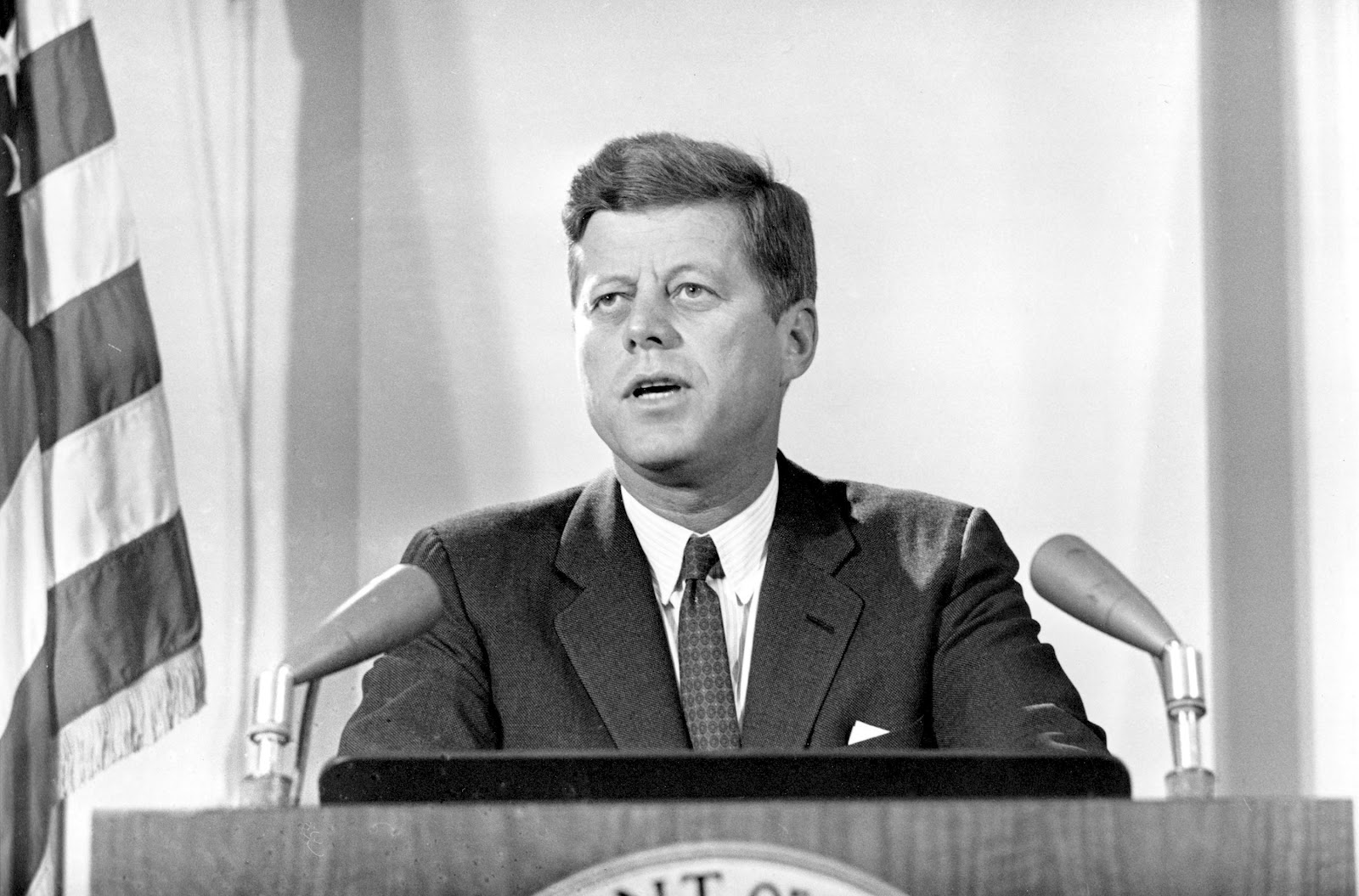

Early in October 1962, the first Soviet SS-4 missiles arrived in Cuba, and American U-2 spy planes discovered them almost at once. President John F. Kennedy knew about them by Oct. 16, but he didn’t go on television and warn the American public of the risk of nuclear war until the 22nd.

He then declared a naval blockade of Cuba, saying that he would stop Soviet ships carrying more missiles, by force if necessary. That would mean war, and probably nuclear war, but at least the blockade gave the Russians some time to think before the shooting started.

The Soviet leaders were now desperately looking for a way out of the crisis they had created. After a few harrowing days, a deal was done: The Soviet missiles would be withdrawn in return for a public promise by the United States not to invade Cuba. The crisis was officially over by Oct. 28, and everybody breathed a sigh of relief. It was closest the world ever came to an all-out nuclear war.

Still, they hadn’t been scared enough. At that time, nobody knew that detonating so many nuclear warheads could cause a “nuclear winter”: The dust and smoke put into the stratosphere by firestorms in a thousand stricken cities would have blocked out the sunlight for a year or more and resulted in a worldwide famine.

What almost nobody knew until very recently is that the crisis did not really end on Oct. 28. A new book by Sergo Mikoyan reveals that it continued all the way through November.

U.S. intelligence was unaware that along with the SS-4s, the Soviet Union had sent more than a hundred shorter-range “tactical” nuclear missiles to Cuba. They weren’t mentioned in the agreement on withdrawing the SS-4s from Cuba, so technically Khrushchev had not promised to remove them.

Castro was in a rage about having been abandoned by his Soviet allies. To mollify him, Khrushchev decided to let him keep the tactical missiles. It was crazy: Giving Castro a hundred nuclear weapons was a recipe for a new and even bigger crisis in a year or two. Khrushchev’s deputy, Anastas Mikoyan, who was sent to Cuba to tell Castro the happy news, quickly realized that he must not have them.

The second half of the crisis, invisible to Americans, was Mikoyan’s month-long struggle to pry Castro’s fingers off the tactical nukes. In the end, he succeeded only by telling Castro that a law (in fact nonexistent) forbade the transfer of Soviet nuclear weapons to a foreign country. In December, the missiles were finally sent home.

So it all ended happily, in one sense — but the whole world could have ended instead. As Robert McNamara, Kennedy’s defense secretary in 1962, said 40 years later, “We were just plain lucky in October 1962 — and without that luck, most of you would never have been born because the world would have been destroyed instantly or made unlivable.”

Then he said the bit that applies to us. “Something like that could happen today, tomorrow, next year. It will happen at some point. That is why we must abolish nuclear weapons as soon as possible.”

They are still there, you know, and human beings still make mistakes.

Gwynne Dyer is a London-based independent journalist whose articles are published in 45 countries.

On October 13, 1962 my family moved to Paris, France. My father worked as a civil servant for NATO attached to the ARMY. (Later my friends wondered if my father was actually a spy but that’s another story).I was barely 15 y.o., a sophomore at Paris American HS. Every Friday night my parents went to the officers club off the Champs with other expats. I was left at home as the family babysitter. When my parents returned home by 9 p.m. I knew something was up. It was then I learned of life under military alert and the world’s fear of the BOMB! I don’t know what life was like here but I can tell you living through this experience as a citizen of the world was illuminating. The International Press wrote about the Cuban missle crisis daily but seeing the grime faces of my parents and their military friends informed me of the seriousness of the situation. At school, teachers pretended to go about life as usual but it was obvious they were living in fear. And this was the first time I had peers who were sophisticated about military, political and international affairs. These kids knew how to talk about these affairs and had facts to support their arguments. I suppose all of us of this generation lost some of our innocence during the Cuban missle crisis but as an American in a foreigh country during this time, this time in history will have an added meaning in my memory when I learned the importance of being a member of the world community.