A few weeks ago I blogged about Sight & Sound’s list of the greatest movies ever and urged you to see some of them. Well, it took some outside pressure, but I’m finally taking my own advice. As part of a poll of critics, I’ve been asked to re-rank Sight & Sound’s top 100 according to my own lights and then provide my own list of the 100 greatest movies not on the magazine’s hallowed list. I have until the end of the year to do both tasks, and I’m hard at work on my own distaff 100. However, I’m also catching up with some of the canonical films of world cinema that, for one reason or another, I hadn’t seen until this year. Today, I give you some thoughts on these classics. There’ll be other posts like this in the future, so stay tuned. The Sight & Sound ranking for each film is from the critics’ poll, not the directors’ poll.

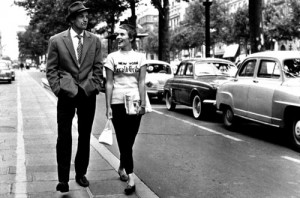

Breathless (À bout de souffle)

Year: 1960

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Language: French

Sight & Sound Ranking: 13

I was actually bored by this one. After Jean-Paul Belmondo’s nihilistic hood goes into hiding with his pixieish American girlfriend (Jean Seberg), the plot comes to a complete stop and concerns itself with their idle banter. The fingerprints of Godard’s subversive crime thriller are everywhere in film history, from the discursive business of Richard Linklater’s slacker movies to the philosophical gangsters of Quentin Tarantino’s early works. There’s no doubting this movie’s immense historical influence. Still, if we’re giving points for historical influence, then Birth of a Nation should be on Sight & Sound’s list. Don’t misunderstand me; Breathless is nowhere near as offensive as Birth of a Nation. I just didn’t find these characters and their chatter to be all that interesting. I was surprised how bored I was; I thought much more highly of Godard’s later work Contempt, which also subverts our expectations to much better effect.

Close-Up (Nema-ye Nazdik)

Year: 1990

Writer/director: Abbas Kiarostami

Language: Farsi

Sight & Sound Ranking: 47

This is a documentary, and yet it is not one, which won’t surprise anybody who’s familiar with Kiarostami’s elusive work. Here’s what happened in real life: A con artist named Ali Sabzian convinced a middle-class Iranian family that he was Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a filmmaker and a personal friend of Kiarostami’s. Sabzian only did it so he could have a few free meals and spend a few hours each day being treated like an important, accomplished person. Here’s what happens on the screen: Kiarostami convinced Sabzian and the family to participate in re-enactments of the incident. He also filmed Sabzian’s trial, though Kiarostami was manipulating events there, too. The movie climaxes on a meeting between Sabzian and the real Makhmalbaf. Those who’ve seen Kiarostami’s other films will recognize the provocative ways in which he blurs the line between reality and fiction. Yet Kiarostami has made better movies since then. I think Close-Up gets its spot on the list because it was the first Iranian film to establish a reputation abroad, a signal to the outside world that vital films were being made even in Khomeini’s theocracy. This is certainly notable, but I think Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry and even Certified Copy are superior.

The Leopard (Il Gattopardo)

Year: 1963

Director: Luchino Visconti

Writers: Suso Cecchi D’Amico, Pasquale Festa Campanile, Enrico Medioli, Massimo Franciosa, and Luchino Visconti, based on Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel

Language: Italian

Sight & Sound Ranking: 57 (tie)

The word that kept coming to mind as I watched this three-hour epic was “sumptuous.” The locations, the décor, the costumes — every frame of this movie looks like a painting by Delacroix or Géricault. Which is only appropriate, this movie being set in the 19th century. Burt Lancaster plays a Sicilian nobleman who lives through Garibaldi’s 1870 revolution to unify Italy and sees the world changing around him. This panoramic portrait of a changing society is much like The Rules of the Game (see below), but it’s told from a different viewpoint. Visconti was born to the nobility, and he didn’t much care for the modern world that was fast encroaching on the world he knew. The title comes from a line spoken by the nobleman: “We were the leopards and the lions, but after us will come jackals and hyenas.” Maybe that’s why this movie’s elegiac tone missed the mark for me. It’s hard for me to mourn the passing of the aristocrats. But oh, the look of this movie! The sun-dappled countrysides! The magnificent villas! The faces of Alain Delon and Claudia Cardinale! There’s even a terrific battle scene in the early going. This movie is a visual feast like few others.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

Year: 1943

Writer/directors: Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

Language: English

Sight & Sound Ranking: 93 (tie)

During World War II, a lot of great filmmakers on both sides wound up making war propaganda. I doubt much of it was as subtle as this epic that follows Clive Wynn-Candy (a fearsome performance by Roger Livesey) from his days as an enterprising young British soldier during the Boer War to a stuffy and corpulent general struggling to keep up with modern warfare. Yes, there are stretches in this film when everything grinds to a halt so the characters can lecture us on the importance of standing up to the Nazi menace. But it’s also a capacious and brilliantly observed portrait of a man through more than 40 years of his life as he learns lessons, has his heart broken, finds his resolve, and tries to stay relevant. This was Powell and Pressburger’s first big-budget movie, and they included a subplot about Candy’s friendship with a German soldier (Anton Walbrook) that landed the filmmakers in trouble with the British government because it didn’t portray the Germans as monsters. (Churchill himself tried to block the movie’s release.) Walbrook is fantastic, especially in a late scene when his aged character seeks refuge in England and describes to his interrogator what happened to his country under Hitler. There are Powell and Pressburger films that I like better, particularly their psychosexually loaded thriller Black Narcissus and Powell’s unforgettable serial killer movie Peeping Tom. Still, this one is well worth the two hours and 43 minutes.

The Mirror (Zerkalo)

Year: 1975

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Writers: Andrei Tarkovsky and Alexander Misharin

Language: Russian

Sight & Sound Ranking: 19

Look, I understand why people adore Tarkovsky’s movies. I really do. They have beautiful, verdant landscapes, and they are uncompromising, tackling the big questions about human existence. I wish I could join in. But I can’t. That’s not just because Tarkovsky’s movies have transcendent moments and deadly dull quarter hours (to borrow Rossini’s saw about Wagner’s music). It’s because Tarkovsky’s pessimism about the human condition is every bit as glib and facile as the optimism that Hollywood feeds us on a weekly basis. This movie is late in his career, too, as his worst tendencies as a filmmaker started to take over, with vague metaphysical portents and symbols taking the place of differentiated characters or anything that might give the audience pleasure. I’m willing to stick with a slow-moving philosophical film, but I need the movie to give me something in return. Actually, what I need is to seek out Andrei Rublev, which is another Tarkovsky film on the list. Maybe that will turn out better for me.

Pather Panchali

Year: 1955

Writer/director: Satyajit Ray, based on Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s novel

Language: Bengali

Sight & Sound Ranking: 42

In a way, this movie benefits from the same factor that benefits Close-Up; when it debuted at MoMA in 1955 (and then when it reached regular American theaters three years later), it made Westerners sit up and take notice that good films were being made in this corner of the world. Of course, not everyone stuck around; François Truffaut walked out of a screening, saying he didn’t need to see movies about peasants who ate with their hands. There’s a whole lot of racism and classism packed into that little remark. Indian cinema has come a long way since Pather Panchali, but Ray’s film (his debut work) has held up well, a beautiful work whose gently lyrical shots of the scenery of West Bengal go hand in hand with its depiction of the increasingly desperate poverty that this Brahmin family falls into.

Rio Bravo

Year: 1959

Director: Howard Hawks

Writers: Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett

Language: English

Sight & Sound Ranking: 63 (tie)

Hawks reportedly made this Western in response to High Noon, a movie penned by a blacklisted Communist writer. Hawks was a political conservative, and he hated the way High Noon depicted the townsfolk as a bunch of cowards who leave the sheriff to battle the bad guys himself rather than risk their own lives. In this Western, they’re properly helpful. This is perhaps more realistic, but I wish Hawks had bothered to create at least a bit more tension. John Wayne plays a sheriff who has holed himself in a jail to keep a killer (Claude Akins) in custody, but the killer’s brother is a rich baddie who’s hired a band of outlaws to spring the inmate, even if it means killing the sheriff, his alcoholic deputy (Dean Martin), a young gunslinger (Ricky Nelson), and the old guy who tends the jail (Walter Brennan). Martin’s perhaps the least convincing cowboy imaginable (even if he’s playing a cowboy named “Dude”), and Brennan’s comic shtick is downright cringe-worthy today, but the movie does have some funny banter as well as Angie Dickinson as a saloon singer who gets caught up in the impending shootout. Even if the subplot involving her is totally retrograde, her smarts still agitate the waters to good effect in this male bonding exercise. This is pretty watchable, but I prefer Hawks’ comedies, and even some of his other male-dominated thrillers like Only Angels Have Wings, to this one.

The Rules of the Game (La règle de jeu)

Year: 1939

Director: Jean Renoir

Writers: Jean Renoir and Carl Koch

Language: French

Sight & Sound Ranking: 4

Damn! How’d I miss this one? Renoir’s scabrous satire of the French upper classes is as dense as a Balzac novel, with its layered, sympathetic portraits of characters rich, poor, old, young, conventional, and rebellious. Yet it feels as light and airy as a Mozart opera, with its comic hijinks and Renoir’s near-mystical sense of camera placement and movement. None of these characters are bad people — in the movie’s famous summation, “Everyone has their reasons,” — and yet their cheerful amorality (illustrated by the multiple extramarital affairs going on) and their obsession with the minutiae of social codes of behavior make them corrupt. No wonder this world is about to be swept away by technological change and (as Renoir suspected privately) by the Nazis. Yet the movie never lectures us. In fact, it’s a lot of fun. The critics polled by Sight & Sound ranked this as the fourth-greatest movie ever. I think that might be too low.

Sansho the Bailiff (Sanshô dayû)

Year: 1954

Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

Writers: Fuji Yahiro and Yoshikata Yoda, based on Mori Ogai’s short story

Language: Japanese

Sight & Sound Ranking: 59 (tie)

This movie runs a scant two hours, and yet it feels more epic in scale and more emotionally draining than many films twice that length. The story, set in 11th-century Japan, begins with a benevolent governor being deposed by a coup and sending his family into exile before he is killed. His son and daughter are separated from their mother (Kinuyo Tanaka), who is forced into prostitution and physically broken. Meanwhile, the adult children, an embittered son (Yoshiaki Hanagi) and a virtuous daughter (Kyoko Kagawa), try to survive under the reign of a cruel bailiff named Sansho. The villain does not win in the end, and yet Mizoguchi names the movie after him because Sansho’s way is so often the world’s way. The filmmakers don’t stint on the horrors visited upon this family, and the whole thing proceeds with a remorseless logic. The female characters fight back against the darkness and often lose, but their actions aren’t completely in vain. In the end, it’s the son who must take his father’s last instructions to heart, “Without mercy, man is like a beast.” This film takes in a great deal of evil, and yet in its conclusion on a desolate, windswept island, it brings home that message in the most powerful way. This is a devastating movie, and yet, like the greatest tragedies, it’s also a blinding light in a dark world.

Beautiful and heartfelt observations. I can only disagree with your take on Breathless. I was mesmerized by the look, intensity and tension, regardless of dialogue. Look forward to your next post.