An upcoming Titanic exhibit designed to showcase the human stories from the sinking of that famous ocean liner in 1912 includes a 26-gem bracelet inscribed with the name “Amy.” That’s just one of 250 artifacts recovered from the North Atlantic’s floor. The items provide a poignant bond to the 1,500 people who died in freezing water in what is considered the world’s most famous maritime disaster.

One story, however, has remained largely untold until now.

It involves a New Mexico rancher, who sank with the ship, and his widow — who never remarried or had children, disowned her family in Texas after a dispute, and mysteriously disappeared. It was only years later that relatives discovered she had died in a Fort Worth nursing home.

“It was something I heard growing up,” Stephenville resident James Pylant said. “My [great-uncle] was the family genealogist, and he knew these people — it was his aunt and uncle.”

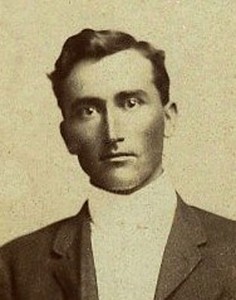

James H. Bracken, a 29-year-old stockman, visited Europe on a buying expedition in 1912 and booked a return passage on the Titanic. He boarded the ship as a second-class passenger in Southampton on April 10 — five days before it sank. His ticket was numbered 220367, ship records show.

Bracken was presumed drowned; his body was never found.

Not long after the ship sank, the American Red Cross established a Titanic Relief Fund to provide financial assistance to survivors and their families in need. An emergency relief booklet published in 1913 listed Bracken as an uninsured husband traveling alone, who had left behind a wife and mother-in-law on a New Mexico ranch that wasn’t worth much because it was dry land without an irrigation system.

The Red Cross established a trust fund to provide support for Bracken’s widow. She had moved to El Paso to be closer to her sister’s family, and the Red Cross deposited her relief funds in an El Paso bank, according to family lore.

But Addie Greathouse Bracken refused to believe her husband was dead.

“I heard that she refused to take the money,” Pylant said.

Pylant was close to his great-uncle, Berry Greenwood. But the difference in their ages was so great that Pylant didn’t get to ask him all the family-history questions he has now.

“By the time I was getting interested in genealogy, he was [developing] dementia,” Pylant said. “There were a lot of things he could have told me if I had done it earlier. Fortunately, he gave me all his notes and correspondence. He had been tracing the family background for at least a dozen years.”

Pylant would eventually attend the National Genealogical Society’s educational program, become a journalist and author, pen a genealogy column for various Texas newspapers, edit American Genealogy Magazine, and serve on the board of directors of Central Texas Historical Preservation Inc. He is currently writing a biography of Texas actress Carolyn Jones, best known for her role as Morticia on The Addams Family.

The piece of family history that most captivated the boy’s mind back then was the relative who died on the Titanic and the widow who couldn’t cope. Pylant was 11 when he began piecing together the couple’s story. Over the years, he talked with relatives, examined a stash of old letters, and researched ship records online.

“I wanted to know what made people tick,” he said. “This fascinated me, that she had disappeared. It’s only been in recent years that I found her death certificate.”

Pylant’s relatives viewed Addie as a curiosity. She refused to believe her husband was dead, spurned the Red Cross’s offer of money, and later shunned relatives as well.

“Addie was angry with the family over something, but nobody seemed to know what it was all about,” Pylant recalled. “She vowed she’d never speak to them again, and she kept her promise. No one knew what became of her.”

She was born in 1881 in San Saba County in Texas and moved to New Mexico with her husband after they were married, around 1907. She went to live with a sister, Lilly, and her family in El Paso in 1918. A few years later, she went to stay with her other sister, Belle, and Belle’s large brood of children in the small Texas town of Carbon, near Eastland. A mysterious fallout prompted Addie to leave a few years later.

“My granddad said she got mad at everyone,” Pylant said. “She didn’t really vocalize what the problem was; it was her body language. They could tell she was upset about something, but she didn’t articulate what the problem was. They took her to the train station, and she said she’d never speak to them again.”

That was the last that relatives ever saw or heard of Addie.

Her mysterious behavior even prompted a family expression — “you’re just like Addie” — used over the years whenever “somebody was being difficult or unforgiving,” Pylant said.

Another relative told Pylant that Addie moved away because everyone kept urging her to get over her husband’s death and move on with her life.

“Addie didn’t want to hear them tell her that he was gone anymore, so she left,” Pylant said.

Addie left behind a trunk that had belonged to her husband. Inside were family photos, an animal pelt, letters, and an empty envelope stamped “Titanic Relief Board.”

In 1967 one of Pylant’s relatives, Jo Faye Phelps, wrote a letter that the Red Cross had made several inquiries about Addie and the relief money that remained untouched in the El Paso bank for years.

Last year, Pylant discovered Addie’s death certificate online. Addie died on May 31, 1969, at a Fort Worth convalescent home. He doesn’t know why Addie ended up in Fort Worth or what she did with her life in the nearly half-century after she got on that train. The Red Cross had provided the information about her death for the certificate, but a spokesperson for that group was unable to locate records about any payments to Addie.

Had Addie finally taken the money?

“Maybe in the end, with no family around, she felt she had no choice,” Pylant said.

Genealogists deal in facts rather than speculation. So Pylant hesitated for a moment when I asked him if the tale of Addie and her ill-fated husband could be described as a love story.

“I would think so, because she couldn’t accept his death, and she never remarried,” he said.

Addie is buried at Shannon Rose Hill Cemetery in Fort Worth.

There’s actually even more to the story. James Holland Bracken was the son of a Civil War soldier, William Bracken of the 12th Kentucky Cavalry, USA. In 1912, James Holland’s father, who was living in Muhlenberg County in Western Kentucky, backed him in a venture to purchase purebred Andalusian cattle in Spain and bring them back to the US. The first Andalusians had been brought to American by Ponce de Leon in the 1500’s and were the ancestors of modern Texas Longhorns, but James Holland wanted the pure breed. His loss on the Titanic bankrupted his father and forced him to move in with his daughter, Mary Jane Bracken Willoughby, the wife of a carpenter. This is where the story continues.

In 1920, Mary Jane’s husband, Grafton Willoughby came to far Eastern Kentucky to work for my great-grandfather building houses for one of the coal towns that were springing up there. Mary Jane and her father, along with the rest of the Willoughby family left Western Kentucky to be with Grafton, but William died in 1921. My great-grandfather gave the family space for his grave in our family cemetery. Now fast-forward 82 years.

In 2003, the family cemetery was moved for road construction and I returned William’s remains to Central City be buried near his wife, Sarah, who had passed away in 1898. Strangely, the plot directly beside her was still untouched after 105 years. It was if she had been waiting for him for all that time. At least they were reunited.

The bodies of some Titanic victims were recovered but not identified and buried in Nova Scotia. James Holland Bracken’s body was not among those identified, but there is a possibility he could be buried with the others recovered. But more likely, he was one of the many bodies that were observed “awash” in the North Atlantic in the spring of 1912.

James H. Bracken is my husband’s great great uncle. I have done much research on this family. I hope to hear back from other relatives. Laura

For some reason, the box with the information about the Titanic exhibit was left off the end of the story. Here’s the scoop:

Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition runs Oct.13 to March 24 at Fort Worth Museum of Science and History, 1600 Gendy St. Tickets are $26 for adults, $18 for children, $19 for seniors, and $6 for members. For info call 817-255-9450.

James’ oldest sister, Mary Jane (Bracken) Willoughby, was my 2nd great grandmother.

I’ve spent the last several years learning all that I can about James and Addie.

James’ Uncle, Asa Bracken, lived in Hale County, Texas and James (at age 18) is found in the 1900 census in his household, that is probably about the time he first arrived in Texas.

According to the Red Cross Committee Report, Addie’s doctor stated that she was so disabled that she would never be able to perform even light household duties for the rest of her life. Does anyone know what her disability was?

This report also stated that the 160 acres that she and James had needed to be irrigated and that they had two years left to occupy the land before the title could be proved. Addie planned on living there until that time and then selling the land.

We have connected before. My husband is related by being Mary Jane’s and James sister Amanda Ann Frances Bracken Hall.

I have copies of the land records from Rosewell.

It seems it bankrupted hisUncle Asa too.

Laura

Someone could probably produce a PhD on a study of the economic effects of the Titanic disaster. Not just the losses of financiers and captains of industry in First Class, but the interrupted plans of enterpreneurs like James Holland in Second Class and not to mention the Third Class and Steerage passengers who were coming to America for a new life. Just think of the contributions to the American economy all of them could have made.