But the big picture “obscures water conflicts at the county level,” said MacMillan, the researcher with Food & Water Watch. (The nonprofit promotes development of safe, sustainable water supplies.) According to the Texas studies, he said, fracking usage is expected to outstrip agricultural use in some counties. And with much of the countryside still in the grip of a major drought that’s not expected to fade anytime soon, that could set up real conflicts.

Theoretically, Texas’ groundwater conservation districts have the power to regulate who gets to pull water. In practice, Texans’ strong tradition of private property rights makes that tough. A major court decision earlier this year, involving the Edwards Aquifer, narrowly limited — but did not deny — the government’s ability to regulate groundwater extraction.

That power may be put to the test again, over the question of limiting groundwater use by gas drillers. While the oil and gas industry is exempted from many water-use regulations, observers believe there’s a chance that the drillers may still be subject to some regulation. That could get tested first in South Texas, where the Eagle Ford shale drilling play is occurring in an area where groundwater levels, mostly in the Carrizo Wilcox aquifer, have been dropping significantly. Although most of the drop is due to irrigation and cities’ water usage, fracking is also a factor.

Kaiser, the A&M professor, said that although fracking’s effect statewide is “pretty small,” in drier areas, gas well activity could indeed be a factor in lowering water tables and making water wells go dry.

The parts of the state that are the most at risk, he said, are the small cities west of I-35. Bigger cities have gone out and acquired water supplies, he said, and some, like El Paso, have built desalinization plants. But in some parts of West Texas, the Ogallala Aquifer has been pumped so low that farmers can no longer afford to drill deep enough to use it, and “little cities are really scrambling.”

Tom Saunders, the Parker County rancher, isn’t in favor of much intervention by government to regulate things like who gets the water. But he has seen the problem developing.

There’s not much drilling going on his home ranch right now, or in Jack County, where the family leases more land. But when the shale gas play was more active (because gas prices were higher), gas drillers were “sucking the [surface water] tanks dry” on the Jack County land, he said, where the water-use decisions weren’t up to him.

“They were paying us for it, but if it didn’t rain, we were short of stock water,” he said. Finally, he said, he talked the gas drillers into sinking their own water well so they’d quit using his stock water — which worked until they burned up their water pump.

“The underground water is going to be very critical, a crucial thing one of these days, because usage is getting bigger with the population,” he said. “These aquifers are just dropping.” Two of his seven windmill-pumped wells went completely dry during the worst of the drought last year, he said. He had to redrill them about 70 feet deeper to hit good water. But he uses that underground water as little as possible, he said.

The Upper Trinity Groundwater Conservation District includes Parker and Montague plus Hood and Wise counties. According to records from the district, between 2009 and 2011 groundwater use by the oil and gas industry quadrupled in Montague and substantially increased in the other three counties. But in Montague, water usage by the oil and gas industry, in each of the three years covered, was 10 times that of public water systems.

Jillian McDonald, public relations coordinator for the conservation district, said officials are in the process of gathering information on 108 water wells across the Upper Trinity, in order to better gauge in the future what is happening to groundwater levels, which have been steadily declining. She said the state sets criteria for how far apart water wells must be and how far from property lines. Gas well companies are treated no differently than other water users, she said.

McDonald said the district strongly encourages water conservation.

Saunders is all for that.

He wishes others would plan more for the long run. When a new neighbor drilled several water wells and put a surface tank at each well, he said, he explained to the man how much water he was going to lose to evaporation. “I said, man, you’re not only using what’s under your land but what’s under everybody else’s as well.”

Saunders said more people should install cisterns to collect rainwater off their roofs. “It’s the purest water you can get,” he said.

********

As with so many other controversies involving shale gas, many Texans feel like they’re at the center of the drilling, but — despite the exertions of Barnett Shale activists — nowhere near the center of efforts to examine, critique, and possibly change that industry.

It was in places like New York and Pennsylvania that fracking’s threats to water quality first drew national attention several years ago. And now the competition for water between drillers and other users in Colorado is drawing more attention to that dilemma.

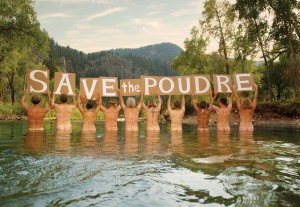

Gary Wockner, director of a group called the Save the Poudre Coalition, has been watching the fracking water usage with concern. His group’s mission is to protect the Cache la Poudre River.

He noted the auction this year in which water haulers serving gas drillers outbid farmers and ranchers for water diverted by a conservancy district from the Colorado River.

The Northern Water Conservancy District, Wockner said, is proposing to divert 60 percent of the water from the Cache la Poudre into a massive “off-channel” reservoir. The district says it needs the water to serve future population growth, Wockner said, “but we see it as a bait-and-switch” because the cities that will buy the water are also planning to sell a lot of it to drillers.

The plan would destroy wildlife and habitat, he said, and also wreck the significant part of the region’s economy based on recreation on that river — fishing, kayaking, rafting, and the like. “The rivers are already in terrible shape this year because of the drought,” he said. The Cache la Poudre flows through the city of Fort Collins, which, with the county and state, has spent millions of dollars protecting open space along the river, building bike paths, and maintaining a natural corridor. “If you drain the river, you really destroy [that] investment,” he said.

And just like in Texas, Wockner said, the available water in Colorado “has already been allotted and counted for. If new users come in, they take water away from someone else — primarily from the farmers and from the rivers.”

Wockner also pointed out a report released in June by a conservation group called Western Resource Advocates, providing new data on the volume of water actually being used by shale gas development. In the study, based on information from Colorado, researchers concluded that estimates of water used in fracking vary widely, but that just in that one state, the industry uses enough water to serve a small city each year.

In fact, the debate over fracking and aquifer depletion has become international. In an article that appeared a few weeks ago in Nature magazine, scientists introduced a new system for better estimating groundwater reserves. And they warned that almost a quarter of the world’s people live in areas where aquifers are being depleted. Those areas include most of the world’s key farming regions — including the High Plains of the United States, where levels of the huge Ogallala aquifer have been shrinking for decades.

Wenonah Hauter, of Food & Water Watch, said the overuse of scarce water supplies by the energy industry was really driven home for her earlier this year at the first Global Water, Oil & Gas Summit — in Dubai.

Her group had gotten interested in water scarcity as an issue several years ago, she said, “and the more we learned, the more it became our main concern.” That interest in turn alerted them to high water usage by the fossil-fuel industry, she said.

But in Dubai, the issue was really laid out. The industry representatives “were very honest about the amount of water to be used,” Hauter said. “There was no pretense about natural gas being a transition to renewable [forms of energy]. This was about getting every drop out of the ground.” There are plans to use fracking on the ocean floor, she said.

At the conference were companies seeking to profit from water scarcity and also from cleaning up pollution caused by fracking and other fossil fuel processes, she said.

Resistance to shale gas development is also growing in other countries, Hauter said. France has banned fracking in most cases, as has Bulgaria, she said, plus at least one state in Germany. The “Global Frackdown” grassroots event planned for Sept. 22 will focus on the local situations in many places around the world.

“It’s an international movement,” Hauter said. “People are terrified about what will happen to their water.”