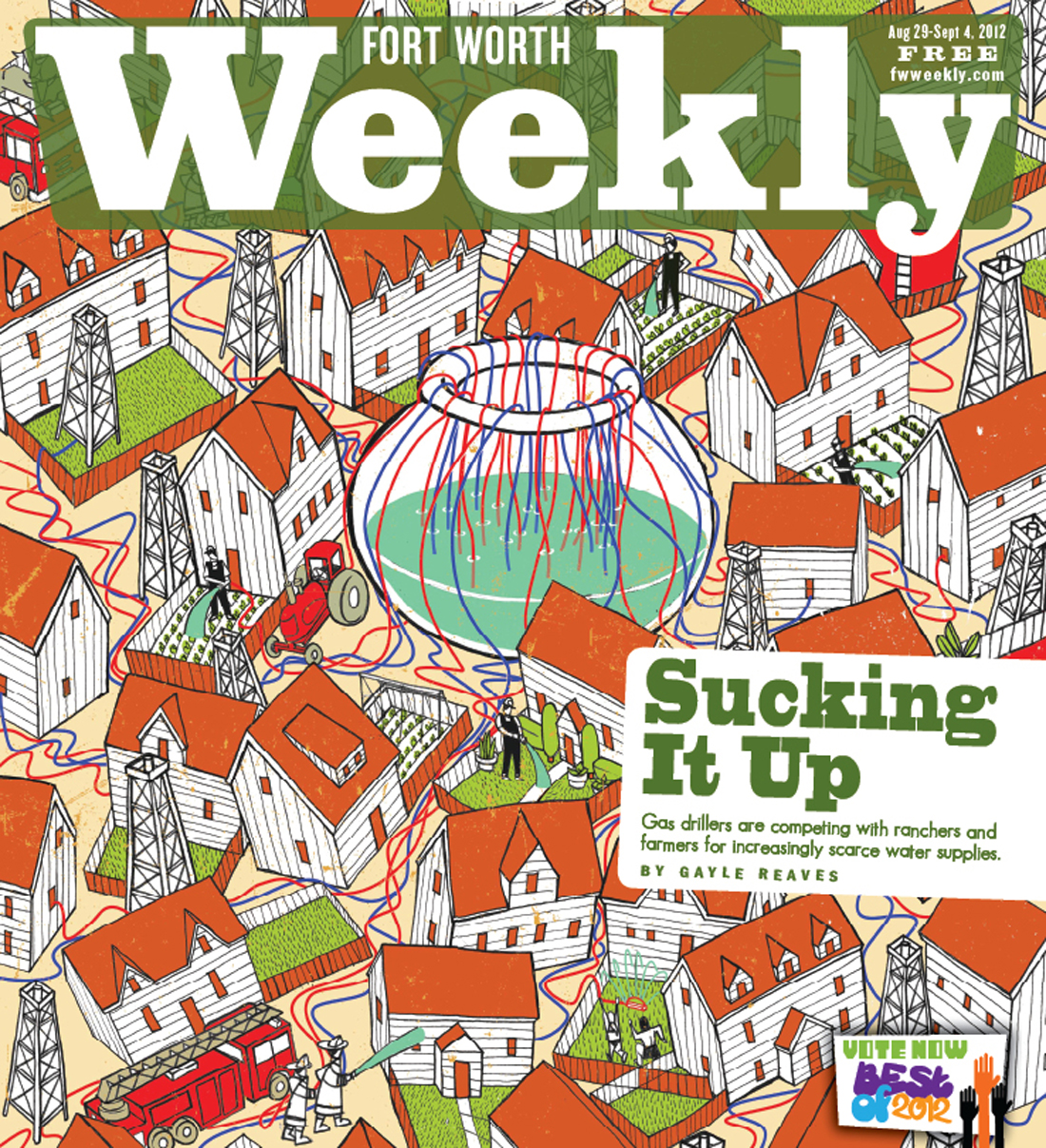

Tom B. Saunders’ family has been ranching for five generations. Surface tanks and wells provide water for the cattle and horses on the Twin V Ranch near Weatherford. He’s got a couple of gas wells on the land too, and he’s not at all opposed to the drillers.

But he’d sure be opposed to selling any of his groundwater to them these days, as he did a few years ago.

“Right now, I’d say, ‘Boys, pray for rain and wait ’til it does. Because I’m not going to sell you any water. My livestock comes first.’ ”

Across much of the West and Southwest, farmers, ranchers, other landowners, and water authorities are having to make those same sorts of calculations. In a growing number of counties in Texas, as well as in big stretches of Colorado and other states, drillers are a growing force in the water market.

In some Texas counties, according to a report from the Texas Water Development Board, the drilling industry now uses more water than farmers and ranchers. In Montague County northwest of Fort Worth, noted Hugh MacMillan of the nonprofit environmental group Food & Water Watch, the state water board “anticipates that the gas industry will use … more than twice what is expected to be used for irrigation and livestock” and almost as much as municipal users. In Stephens County, “drilling and fracking the Barnett Shale is expected to consume more than three times the consumption for irrigation and livestock.”

In Colorado recently, when a major water district held an auction of “surplus” water diverted from the Colorado River, haulers supplying the drilling industry outbid farmers and ranchers. When ranchers and farmers can buy water, it will be more expensive — not only because of competition from gas drillers, of course, but because of continuing drought, shrinking reservoirs, growing populations, and dropping groundwater levels in many parts of the country.

“Really, we have plenty of water in Texas, but the days of cheap water, of easy to develop water, are gone,” said Ron Kaiser, professor of water law and policy at Texas A&M University. Although groundwater supplies of fresh water are dwindling — alarmingly, in some places — there are “huge amounts of brackish groundwater” under Texas he said. That water is far too salty to drink, “but we have the technology to make it very [drinkable],” he said.

Who can afford that technology? Cities, probably, he said, by raising rates. But “agriculture can’t pay those prices.”

Questions about the effect of widespread shale gas development, using millions of gallons of water per well, on water supplies aren’t confined to Colorado or a few counties in Texas. Nationally and internationally, environmental and water rights groups are beginning to raise concerns. In September, activists in several countries are planning a “Global Frackdown” event to draw attention to those and other problems they see with shale gas drilling.

A national poll by the Civil Society Institute, released a few weeks ago, found that three out of four Americans — including 61 percent of Republicans — are worried about shortages of clean water, want federal action to address increased drought, and have made the connection between energy industries and water usage.

Heather White, general counsel for the Environmental Working Group, which has worked with the Civil Society Institute on many projects, said that water quantity and quality are the “number-one environmental issue” for people in this country.

Even in states like Texas and Louisiana, where the oil and gas industry is so powerful, she said, people are starting to question the exemptions for those industries from so many laws that other businesses must follow and that affect water supplies.

“Americans are waking up,” White said. “It’s Washington that’s out of step.”

********

In the broad picture, hydraulic fracturing as part of gas drilling accounts for less than one percent of water usage across Texas.

The problem is that water isn’t distributed evenly across the state — it’s a very local proposition.

“As you get down to the local level, [water use by gas drillers] becomes more of an issue,” said Robert Mace, deputy executive administrator for science and conservation at the Texas Water Development Board.

The agency, which underwrites water development projects for local government bodies, doesn’t take any position on the use of Texas’ water by gas drillers. Board officials know the issue is out there, but they haven’t tried to track the conflicts. In Texas, water politics are always about who has it and who doesn’t, and the fights historically have been fierce. With much of Texas — and more than half the counties in the country — in drought status, the battles will only get bloodier.

The drought hasn’t been as severe in 2012 as it was last year — the state’s worst drought ever recorded — but it hasn’t gone away. Texas is like the proverbial frog in the pot, Mace said: “The heat has been turned down from high to medium” — but the implication is that the state’s water resources are still getting cooked.

In a presentation he made this week, Mace noted that the state definitely is not prepared for a “drought of record,” like the one that lingered on in Texas in the 1950s.

Even in the big picture, the impact of shale gas drilling is being felt. According to a recent report by two University of Texas researchers with the Bureau of Economic Geology, drilling in dry areas of the state could contribute to lowering groundwater levels and reducing some stream flows. They estimated that net water usage for fracking in Texas could roughly triple by 2030 and then decline.