About 9:30 a.m. on June 7 last year, workers at the Fort Calhoun nuclear power plant near Omaha, Neb., raised the alarm.

Some minutes earlier, an electrical fire had sparked in a large fuse box –– the result of poor installation and inadequate cleaning. The fire spread. Soot and smoke knocked out the cooling system for the pool where a radioactive fuel rod was being stored. The safety system was disabled for 90 minutes, causing the pool’s temperature to rise by several degrees.

The accident didn’t result in leaked radioactivity or major damage to the power plant, which was already temporarily shut down as a result of flooding.

Still, the outcome could have been worse.

“They were a long way off from a serious accident, but the point is –– it’s not supposed to happen,” said Arnie Gunderson, a former nuclear engineer and vocal critic of the industry. “The problem is that the spent fuel rod could have been hotter, in which case they wouldn’t have weeks [before a meltdown], they would only have a day or two.”

Afterward, Fort Calhoun quickly became the center of an ongoing debate between staunch defenders of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, charged with regulating the country’s nuclear reactors, and critics who believe the deeply divided federal agency isn’t doing enough to ensure that the industry is protecting the public from the dire consequences of nuclear accidents.

Questions about the agency’s commitment to safety don’t end there. Last year, for instance, an investigation by the Associated Press found widespread problems with the aging nuclear plants –– many of which are being given license extensions by the NRC.

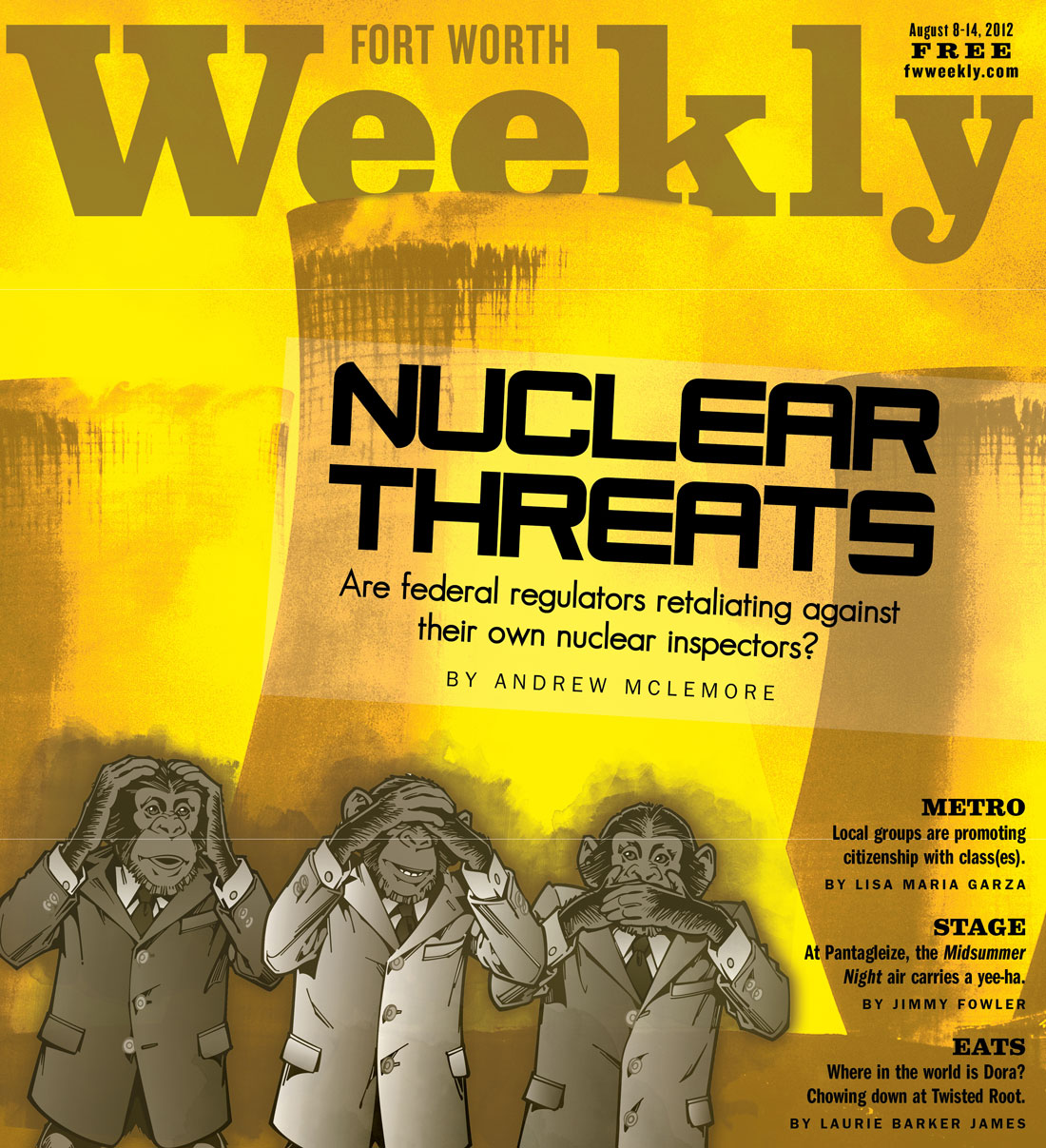

The heat has now been turned up on the debate by an anonymous letter, supposedly written by several of the commission’s own inspectors in April, raising questions about the performance of an NRC supervisor in the agency’s Arlington office. The unnamed inspectors accuse the supervisor of downplaying the significance of the Fort Calhoun accident to avoid problems for himself.

More broadly, the inspectors said they work in a “corrosive environment” that is impairing the “effective oversight of the commercial nuclear industry.”

The supervisor’s response raises even more concerns. While defending his own actions regarding Fort Calhoun, Troy Pruett in essence confirmed the letter-writers’ allegations that, in the NRC, raising safety concerns is a surefire way to draw bosses’ criticism.

And in fact that has proven true for the man who was at the top of the NRC hierarchy until recently. NRC chairman Greg Jaczko resigned a few weeks after the letter appeared, under heavy criticism from the nuclear industry for his aggressive push to address longstanding safety problems at the country’s 104 nuclear power plants.

The allegations in the inspectors’ letter don’t refer specifically to the Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant near Fort Worth, which that office also oversees, but they have renewed old complaints about how the agency responds to inspectors who push for new and better safety standards.

Six sources whom Fort Worth Weekly contacted for this story — including nuclear engineers, experts, and former employees — said they were aware of instances when commission managers criticized or even retaliated against employees who raised safety concerns.

“These allegations, if true, are appalling,” said U.S. Rep. Edward J. Markey, a long-time critic of the agency to whom the inspectors’ letter was delivered. “I have long been concerned by the commission’s voting record on safety matters.”

The Massachusetts Democrat released the letter publicly in May and called for an immediate investigation. Commission spokeswoman Lara Uselding said the NRC’s Office of the Inspector General, an independent operation whose sole purpose is investigating possible misconduct, is looking into the claims. There is no timeline for the investigation, and she declined to comment further.

Activists and former agency employees describe a culture in the NRC that discourages dissent while simultaneously promoting those who ignore safety concerns to avoid embarrassing the agency.

Possibly as a result of that culture, the commission has responded slowly to safety concerns raised by its inspectors. At the Nebraska nuclear plant, even after a critical cooling function was disabled, it took 10 months for the commission to decide if what had happened represented a serious safety threat.

Ultimately the NRC slapped Fort Calhoun with a “red” safety finding, the highest level of sanction and one of only six such findings issued since 2001. Depending on whom you ask, that’s either an endorsement of the agency’s success at addressing safety issues before they become problems or an indictment of a system that downplays the possibility of real danger.

In the wake of last year’s disastrous meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi plant, nuclear watchdogs want to know if federal regulators are putting industry interests before public safety. Even from across the vast Pacific, the Japanese nuclear disaster may still affect Americans, as currents of wind and water continue to spread the contamination.

“If we’re operating in a culture of denial of safety risk, that puts everyone at heightened risk,” said Karen Hadden of the SEED Coalition, a clean-energy group based in Austin. “Anyone near a reactor is at increased risk until this is straightened out.”

********

This time, the pot is calling the kettle a bureaucrat.

In Troy Pruett’s long, articulate response to accusations that he smothered safety issues at Region IV, he doesn’t just defend himself –– he provides a litany of examples of other NRC supervisors who have tried to stifle his own attempts at regulation through the years.

As in, I’m not the problem, but oh boy, let me tell you about the people who are.

During his first year at the NRC in 1992, Pruett recounted, he pushed for a new way of enforcing a certain regulation. A supervisor told him it would “end his career” if he didn’t back off. As an inspector for the Waterford nuclear plant in Louisiana, Pruett said he once again “pushed the limits on regulation” and was told by senior NRC managers: “One more strike and you are out.” Later, when he managed inspectors at the Clinton plant in Illinois, his team was criticized for concluding that the plant owners were violating many security requirements.

“I have written or issued more violations of NRC requirements than most NRC staff,” Pruett said. “Given my proven track record, it is simply outrageous to think I would ever suppress violations of NRC requirements.”

Pruett sent his letter to the House Ethics Committee, demanding that Rep. Markey be publicly reprimanded for damaging his reputation. He said it was no secret that he opposed, and still opposes, the “red” safety finding for the Fort Calhoun accident. But he never tried to silence inspectors who disagreed, Pruett wrote.

“Some blatant false statements were made,” he said, referring to the letter’s accusation that he ignored safety concerns to avoid a “political environment” that would make it difficult to get Fort Calhoun up and running again. “I fully support the performance of any outside or internal investigation and wholeheartedly believe the NRC and I will prevail.”

There are some reasons to believe Pruett.

David Lochbaum, director of the nuclear safety program for the Union of Concerned Scientists, has long heard the complaints about the NRC’s efforts to suppress its inspectors’ safety concerns and the agency’s record of allowing safety issues to take a back seat to the wishes of the nuclear industry.

“They do have bonuses [for employees] that are based on not making waves,” he said. “So their bonuses are more for delivering a project on time as opposed to raising a safety issue or identifying a problem at a plant.”

Despite those acknowledged problems, Lochbaum was cautious in his reaction to the anonymous letter and its accusations.

It surprised him because the Region IV office in Arlington has long been considered the agency’s most aggressive regulator, Lochbaum said. And though he doesn’t personally know Pruett, he said, he’s heard of the supervisor’s strong reputation.

“If [the charge is that] Region IV was discarding safety concerns, those data points don’t seem to support it,” Lochbaum said.

The letter describes Pruett, the deputy division director for reactor projects, as reacting contemptuously to staff members who raised questions about safety at Fort Calhoun and says that two NRC employees quit as a result.

The letter also says the NRC creates incentives for not pointing out safety issues. The agency is less likely to give out bonuses to inspectors whose safety recommendations are challenged by the nuclear plant owners and then overturned by the NRC.

“Mr. Pruett has openly criticized and denigrated professional staff during inspection debriefs for identifying inspection findings that he either failed to understand or that he disagreed with, based on his myopic perceptions,” the letter said. “These actions have resulted in a chilled environment.”

When Markey made the letter public, he accompanied it with a press release expressing his concerns about the nuclear commission’s voting record on safety issues over many years.

Lochbaum said he trusts the NRC’s Office of the Inspector General to do a thorough and fair investigation. Regardless of the outcome, it’s not a bad idea to take a closer look at how the NRC is handing safety inspections, he said.

“Either way it turns out, it’s a positive,” he said. “If your roof has a hole in it, you don’t know until it rains. We’re going to see how good the NRC’s roof is.”

Lochbaum isn’t the only one with concerns. He and other nuclear watchdogs provided several examples of the NRC’s tacitly allowing safety issues to take a back seat. And Region IV has a history of retaliating against employees who blow the whistle on misconduct.

********