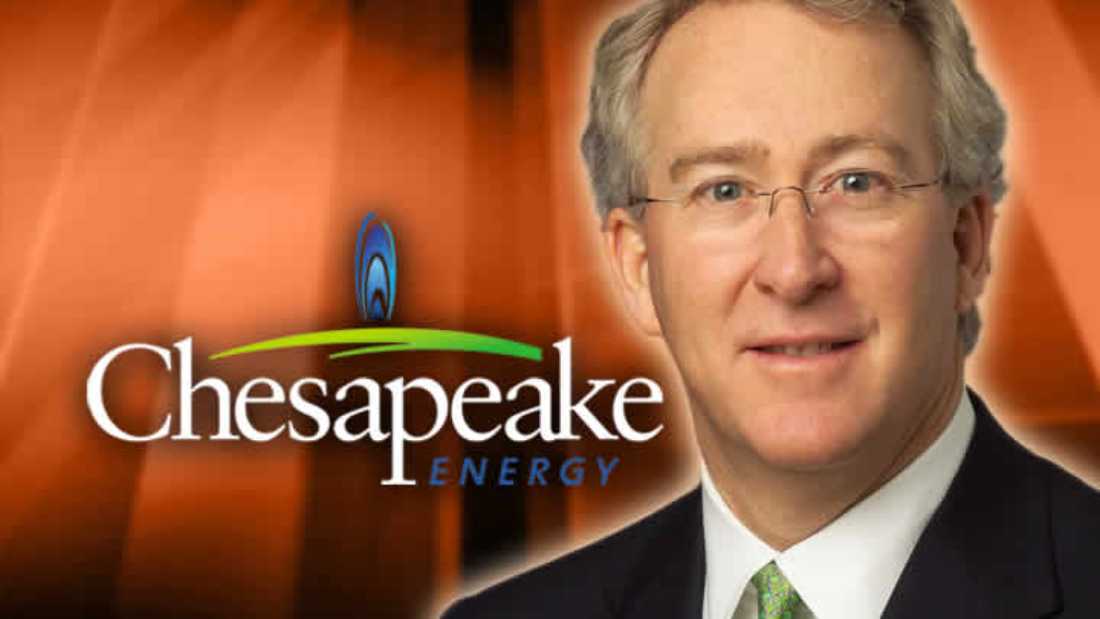

The demise of Chesapeake Energy continues to unfold. After news of $1.1 billion in unreported loans, Reuters exposed a $200 million hedge fund that CEO Aubrey McClendon ran from company headquarters. This fund invested in the same commodities that Chesapeake produces. Sen. Bill Nelson has called for the Department of Justice to look into possible fraud and price manipulation.

These issues of corporate governance and questionable financial engineering are breathtaking. But let’s step back and examine the full import of shale gas economics. Chesapeake may simply be a microcosm of a much graver, systemic problem.

While we were enjoying the exceptional economic party of the last 20 years, corporate America rose to new heights, and an interesting dynamic quietly slipped into place — what I call the two economies: one real and one virtual.

The real economy is based on actual goods and services. The virtual economy is based on a perception that goods and services exist.

Financial markets are meant to provide capital to legitimate businesses for commodities or products supplied to people who need them. Public relations has an obvious role in promoting such commodities and services, but somewhere along the way, we began to replace legitimate products with spin.

Around the globe, the gas industry has claimed shale reserve figures that are off the charts. The U.S. Geological Survey recently cut such estimates by 80 percent for the Marcellus Shale. The Polish government slashed estimates there by 85 percent and now estimates are being lowered in India. But those original, inflated claims were enough to “froth the market” — to draw a huge influx of cash from Wall Street, perhaps more than the real reserves are worth.

In this virtual economy, it is no longer necessary to show proof of an actual widget or a truly proved natural gas field. The Powers Energy Investor noted that Chesapeake claimed its Fayetteville wells will produce an average of 2.6 billion cubic feet of gas. But not a single well has ever produced more than 1.7 bcf, according to state agency data. Most are doing good if they produce 1 bcf, and the average for all Chesapeake wells is about half that.

In the shale gas business — and in who knows how many other areas — we seem to have created industries where money chases spin on a vast scale. Not products, not services, just the idea of those things.

It was a logical progression. We had already shifted from a manufacturing economy to a less tangible, service-based economy. And the internet has accustomed us to virtual realities.

A few years ago the financial institutions started bundling questionable mortgages and shifting them around. Now the gas industry is bundling and shifting leases in a land grab that McClendon himself bragged made him more money than actually drilling. During an earnings call he said, “I can assure you that buying leases for x and selling them for 5x or 10x is a lot more profitable than trying to produce gas at $5 or $6 per million cubic feet.”

Try producing gas at $1.85 per mcf.

Like actual assets, the perception of assets can be shifted to make money. McClendon borrowed $1.1 billion against assets of a publicly traded company that he ran, without adequate disclosure to shareholders.

During the past decade or so, income inequality in this country has increased hugely. The average CEO total pay package is over $400 million for the top 10 CEOs in America, while the worker bees haven’t kept up with inflation. And yet it was the workers who actually created that $400 million in wealth. McClendon apparently made $63 million in 2011 by participating in wells using someone else’s money to pay expenses — although such actions were forbidden to other executives at his company.

Small business owners have to actually provide something real in a legitimate exchange. Billions of dollars are not available to them to swap for inside trades that may be based on nothing more real than superb BS.

And yet small business owners are the ones who have been impoverished. Their businesses have faltered and struggled. They are also the largest provider of net new jobs in the U.S., in spite of all the oil and gas industry’s rhetoric.

In other words, the real economy has been derailed by its avatar.

Considerable off-balance-sheet financing can hide a multitude of sins. Unmitigated greed at any cost is never sustainable and is no alternative to real goods and services.

It’s as if we believe our own internet fiction: that virtual economies and perceptions can replace the real thing.

Deborah Rogers, a former investment banker who lectures widely on shale gas economics, can be reached at deborah300@sbcglobal.net.

Great article. I’m glad someone pointed the inflated figures out. It seems like every website I go to, it says there is more and more gas than the previous site. One said it would like 10 years, another I read said there was enough gas to last 100s of years! I don’t know who to believe! I like to visit shalestuff.com to get very straight forward, non-inflated, non-biased information on what is happening in the Shale Gas Industry.