Alan Bean couldn’t miss the headline splashed across the top of his hometown paper one summer morning in 1999. It spoke of big news for the 5,000-person burg in West Texas: a big drug bust that landed a sizable portion of the town’s black community behind bars.

“Tulia streets cleared of garbage,” the banner headline read. Like many aspects of the American war on drugs, the wording smacked of insidious racism.

Bean recalled his reactions to that news story a few days ago, to a roomful of people at a Fort Worth hotel. The event, examining the 40-year-old war on drugs and its disproportionate impact on minority communities, was hosted by the Tarrant County Libertarian Party but drew speakers from several parts of the political spectrum.

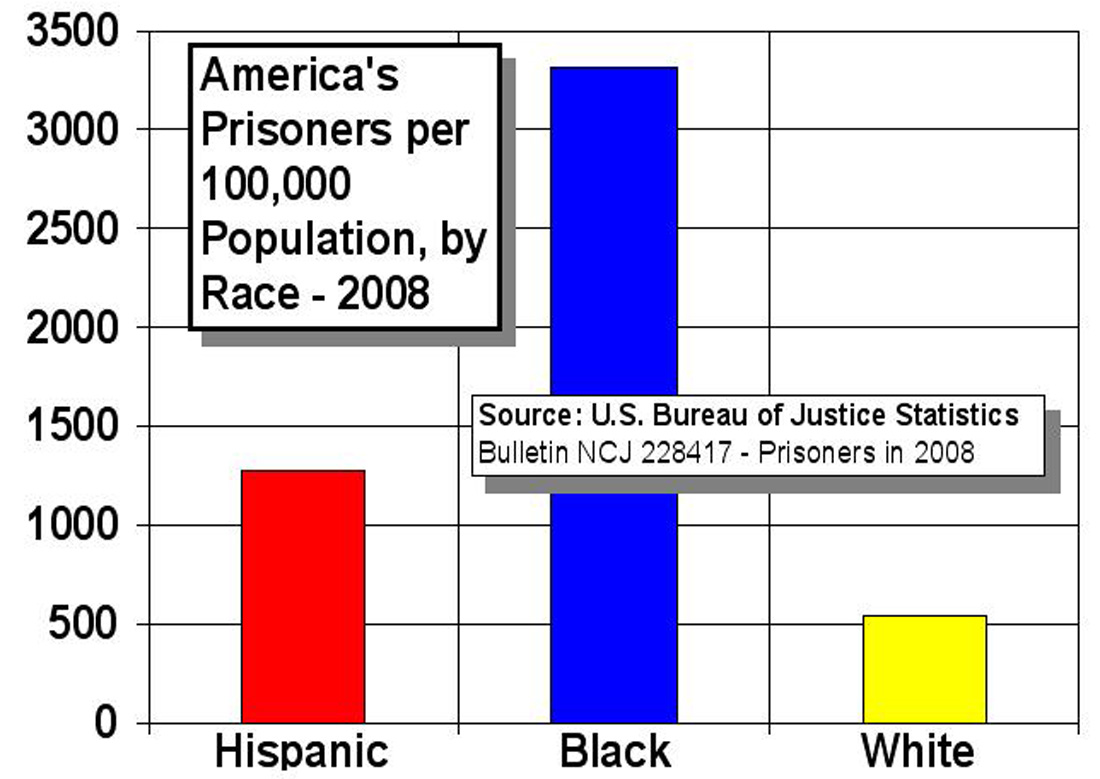

At the podium, Bean acknowledged that he’d known nothing of the lopsided statistics when he picked up the paper that morning. The drug bust in his small town would change all that, though, and suddenly push him to the front lines of a war that locks up seven black men for every white man incarcerated in the United States, devastating minority neighborhoods while white enclaves, where drugs are every bit as prevalent, are left mostly unscathed. The more Bean read and researched, the clearer the drug war’s racism became to him.

But that drug bust was the eye-opener. On that July 23 morning, dozens of police officers in tactical gear swarmed the black neighborhoods of South Tulia and pulled 47 people, many still in their underwear, out of their homes and arrested them on charges of selling powder cocaine to undercover officer Tom Coleman, a sheriff’s deputy who had posed as a drifter. Thirty-eight of the defendants were African-American, representing roughly 15 percent of the town’s black community.

Bean wondered how a town Tulia’s size could have enough drug users to sustain 47 drug lords. And powder cocaine? That’s a drug of affluence, something you’re more likely to find in Dallas high-rises than in dusty neighborhoods where crack is far cheaper and more prevalent. Also he’d never heard of Tom Coleman.

Bean, an ordained Baptist minister and Canadian native who was relatively new to town, shared his misgivings about the sting later that week at church. A white businessman pulled Bean off to the side and offered some local context.

“The sting was all about these young black males who were sports stars in high school but never left town after graduation,” Bean said the businessman told him. “They think they can do drugs, mess with our girls, and get away with it.”

He’d heard enough. Early meetings with local sympathizers became the Friends of Justice, a group that now operates out of Bean’s office in Arlington. The group initially aimed to get to the bottom of the Tulia busts, even if the effort got him run out of town.

“The Tulia defendants weren’t being prosecuted for selling drugs, I realized,” Bean said. “They were going down for not having a job, not paying a mortgage, not maintaining a marriage, and not tucking their children in at night. So long as they were demonstrably deficient as parents and breadwinners, the fact issues of a particular case were irrelevant.”

The facts did eventually come out in the Tulia case, but only after a district judge handed down extremely harsh sentences, like the 50-something-year-old man slapped with 90 years for allegedly selling a few grams of coke to Coleman. Civil rights lawyers and journalists who flocked to Tulia unearthed a litany of flaws in Coleman’s investigation. The officer’s own checkered past came into question too. By the time the dust settled a few years later, Gov. Rick Perry had pardoned most of the Tulia defendants, and in 2005 a jury found Coleman guilty of perjury. A visiting district judge sentenced him to 10 years probation.

To many like Bean in the civil rights trenches, Tulia offered chilling evidence that the federal war on drugs had devolved into a thinly veiled race war that’s had basically zero effect on drug consumption, availability, and related crime.

“Tulia was America writ small,” he said. “The drug war was a public policy response to conditions in economically starved inner-city neighborhoods, but the social dynamics are more visible in small, pissant towns like Tulia, because everything is small, and therefore simple.”

A 2010 federal survey found almost identical rates of drug use among whites and African-Americans. Yet minorities — particularly African-American males — make up a staggering majority of drug-war inmates.

The Drug Policy Forum of Texas estimated, based on federal numbers, that whites represented 74 percent of U.S. drug users in 2010 but only 19 percent of drug-related inmates. That year, blacks, representing about 11 percent of total drug users, made up 56 percent of drug-war inmates. Latinos were 10 percent of users and 22 percent of inmates.

“The war on drugs is really a war on black and brown people,” said Jasmine Tyler, deputy director of the Drug Policy Alliance, an advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. “We aren’t worried about drugs. If we were worried about the effects of drugs, we’d stop them from entering the country at the border. What we have is a tactic that’s used under a guise of public health and safety which really has nothing to do with either of those two areas. The drug war really is the new Jim Crow.”

Tyler believes the disproportionate effect on minorities stems from both subconscious discrimination and outright racism.

Other reformers, like Carl Veley, a Drug Policy Forum speaker from Houston, attribute much of the apparent racism to convenience: Drug dealers in low-income neighborhoods conduct business on street corners and other open places like public parks, where it’s easy for police to make arrests.

“Police are rewarded for the number of busts they make,” Veley said. “It’s much easier to make a $5 bust over in the black neighborhood than a $5 million bust over in the white neighborhood or even a $50 bust in the white neighborhood.”

He cited conversations with police officers who told him they look at the disproportionate numbers of incarcerated blacks as clear evidence that crime is more common in black communities, which the statistics seem to call into question.

“They operate on the assumption that the justice system is absolutely fair and perfect,” Veley said. “I look at that data and say there’s clearly something wrong with the justice system.”

Critics from across the political landscape have been saying for years that Washington is losing the drug war. Drug usage levels have barely changed since Richard Nixon declared the war in 1971.

The only drug for which usage rates have dropped during the past 40 years is tobacco, as Drug Policy Forum activist Suzanne Wills dryly noted at the Fort Worth gathering.

Gil Kerlikowske, President Barack Obama’s drug czar, told the Associate Press in 2009 that the drug war has “not been successful” and that “40 years later, the concern about drugs and drug problems is, if anything, magnified, intensified.”

That’s why critics are calling for a return to the drawing board and a new national debate about how state and federal officials can more effectively attack a problem that many see as better addressed by doctors than law enforcement. They’re also worried that what they see as the institutionalized racism involved is doing long-term harm to minority communities.

Every arrest means more cost to taxpayers for prosecutions and prisons, the speakers pointed out, as well as costs to the overall economy from the self-perpetuating cycle of usage, crime, and imprisonment.

Veley said it’s crucial that minority leaders, above all, are brought into that debate.

“Black leaders look around them and say, ‘Oh my God, drugs are terrible. They’re ruining our country,’ ” he said. “Then they make the logical leap and say drugs are terrible, they must be illegal. That doesn’t follow.”

Great article on a great event, Matthew ! Thanks so much for coming.