In the late ’00s, an independent label based in New York City, Norton Records, put out a three-volume set of songs from Fort Worth’s “teen scene,” a short period in the mid-to-late 1960s when teenage boys picked up musical instruments and began emulating The Beatles, who had exploded into the American consciousness via The Ed Sullivan Show on Feb. 9, 1964.

The box set was revelatory. When it was released, few people here had any idea that not only had Fort Worth had a teen scene but that it was exceptional enough to warrant the box-set treatment from a super-hip retro record label. With the current wave of independent, progressive, mostly rock music building, the box set seemed to reinforce what a lot of folks were thinking: that Fort Worth was a pretty damn cool, hip music city.

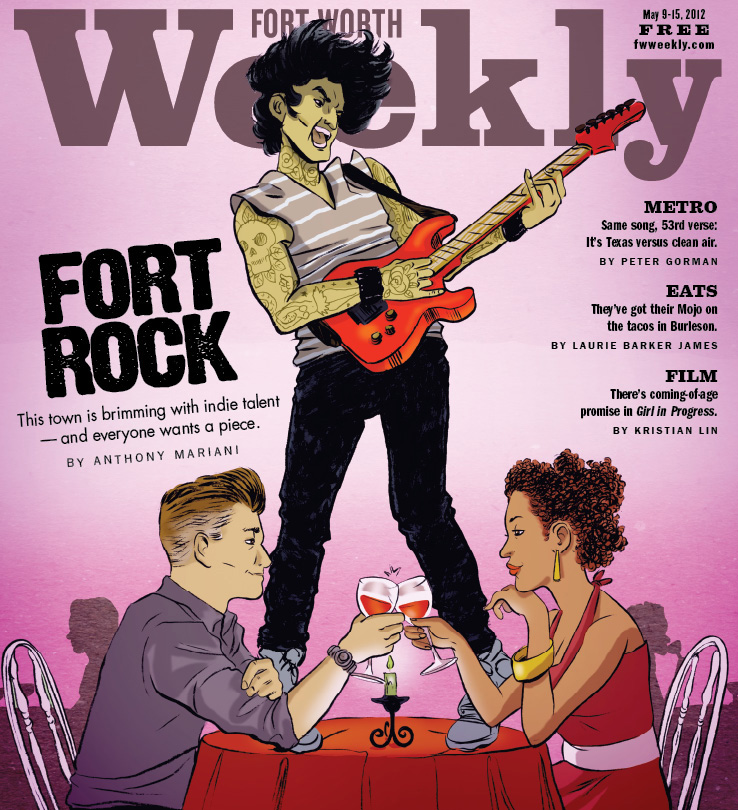

Sure, Fort Worth has had its share of legendary, progressive, independent rockers (T Bone Burnett, Delbert McClinton, The Toadies). But the city arguably has never had as many progressive, independent rock bands as today and certainly not as many exceptional rockers. And we’re not the only ones who have noticed. In a conversation last summer on Dallas Observer’s music blog, DC9 at Night, several participants agreed that Fort Worth’s scene is the hottest. “Crazy Fort Worth is having an especially good year comparatively,” said Mark Schectman, host of The Local Edge on The Edge (KDGE/102.1-FM) — not only because of “the sheer number of good bands,” he said, but because a few of them “are releasing some really stellar music right now.”

You’d think that with all of this fertility, there’d be plenty of cool places in town that regularly host live, original, mostly rock music. But you’d be wrong. Yes, the number of places for live music has skyrocketed recently. But most of them are bars or bar/restaurants that also offer karaoke or cover bands, not places exclusively devoted to original independent music or to building any sort of original indie scene.

“There is a bit of overkill,” said veteran musician Jordan Roberts, co-songwriter for Calhoun and former member of The February Chorus and Audiophiles. “Sometimes you just want to go somewhere and talk to your friends and not have a loud band.”

Even though the number of good rock bands has increased over the past few years, the number of original-rock-first venues has stayed the same –– or maybe even decreased. “It’s a really weird time in Fort Worth right now with so many super-good bands and probably the lowest amount of original music venues,” said veteran musician Ray Liberio, who plays in The Me-Thinks, Vorvon, and Stoogeaphilia.

Well, so what? Local musicians will play wherever they can make some scratch. But they would rather get onstage and not compete with TVs tuned to sports and loud talkers getting wasted. And without places for only (or mostly) original, progressive, indie music, indie musicians will be forced to ply their trade out of town –– or pack up and ship out for good.

In a recent conversation, Chris Maunder, former owner of the shuttered Moon, a popular genuine venue by Texas Christian University, mimicked what he believes some venue owners, less committed to original music, think: “Because we’re a new bar, we’re gonna take that original music that you have been working so hard on and take advantage of what you’ve built, because we have to have live entertainment,” he said.

It is to local bands’ credit that they’ve built up the crowds that now are clamoring for live music, but some bar owners are just being users, he said. “Where were you 10 years ago, when it was just a couple of us venues and bands working their asses off?” he asked.

[pullquote_left]Without original, progressive musicians, you won’t have genuine rock venues, and without genuine rock venues, your city loses some of its soul — and its appeal to newcomers.[/pullquote_left] Should non-music fans care about all this? Yes. Without original, progressive musicians, you won’t have genuine rock venues, and without genuine rock venues, your city loses some of its soul — and its appeal to newcomers. Progressive, independent rock inspires the kind of sizzle that encourages the construction of cool restaurants, condos, and retail establishments, leading to revitalized neighborhoods. Big-money developers certainly care. So should the city.

********

Fort Worth city government, however, hasn’t always been helpful. First, there was the ado over the Ridglea Theater, a huge, beautiful former heavy-metal club that could have filled Fort Worth’s need for a large rock venue. Jerry Shults, owner of the Gas Pipe regional chain of smoke shops, bought the entire complex two years ago, saving it from certain demolition, with plans to turn the theater into a concert venue and fill the complex with a small bar and a mid-sized venue, a second version of The Moon. But he ran into opposition from council member W.B. “Zim” Zimmerman, who scared off Maunder. Now Shults seems to be leaning toward turning the Ridglea into an “event center” that would book rock shows only occasionally.

Second, there’s the new noise ordinance, severely restricting the decibel levels of performances in or near residential areas such as West 7th, the Near South Side, and Sundance Square.

The few genuine rock clubs in town now seem to be doing OK, although it’s not always easy to tell. The Where House is BYOB, and 1919 Hemphill doesn’t allow alcohol at all. Based on reports from the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission, Lola’s Saloon and The Grotto, probably the two most popular remaining genuine rock venues, seem to be doing well. If you go by anecdotal evidence, the clubs seem to be doing even better. They’re all pretty packed on a regular basis, especially when the shows are big and Fort Worth-local.

“We’re missing The Moon,” Liberio said. “But it’s not like a lot of places closed down. It’s just that there’s a lot of great bands all the sudden, which makes it hard to get a gig.”

Everyone seems to think that until Fort Worth is home to a nice, decent-sized venue, something along the lines of Dallas’ 1,700–seat Granada Theater, the kinds of touring acts that bring people out will skip playing here. The Fleet Foxes and Black Keys of the world will hit Dallas, leaving the average mid- to lower-level touring act to Lola’s, The Grotto, or The Where House, and, let’s be honest, local music fans have a hard time caring about some touring band they’ve never heard of. They seem to either want to see local bands (including ones from Dallas and Denton) or major bands (like Fleet Foxes or Mumford & Sons), not the in-between stuff.

Case in point: the Dead Meadow show at Lola’s a couple of weeks ago. Fort Worth/Los Angeles super-group EPIC RUINS opened the concert, and after they finished, the whole room pretty much emptied out. Dead Meadow is a badass L.A. band, but no one here had ever heard of them.

The unwritten rule is that if you’re a club owner or agent booking any sort of mid-tier touring act in Fort Worth, you’d better book a Fort Worth artist or two as openers.

While a Granada Theater West seems far off, there are a couple of candidates that could help alleviate the problem.

On the Benbrook traffic circle, the Cendera Center, a 16,000-square-foot events facility, recently opened. Closer in, Live Oak Music Hall & Lounge is slated to open in mid-June and will be ideal for mid-tier touring artists. The finely designed Near Southside listening room seats about 500.

Live Oak booking agent Clint Simpson said he wants to attract artists along the lines of Ray LaMontagne, Trombone Shorty, and Amos Lee.

[pullquote_left]The unwritten rule is that if you’re a club owner or agent booking any sort of mid-tier touring act in Fort Worth, you’d better book a Fort Worth artist or two as openers.[/pullquote_left] Local musicians are excited about Live Oak’s prospects. “It will be the premier place in Fort Worth, one of the gems of North Texas,” Roberts said. Once fans have been there, he said, “they’ll go back to see bands they don’t really like because it’s such a cool place.”

Live Oak is the first venue built specifically for music since the beloved Caravan of Dreams closed in the late 1990s.

Genuine rock club owners also see Live Oak as a major plus. “I think the Live Oak is going to be cool as shit,” said Lola’s owner Brian Forella. “I think it will be a kickass next great addition to this town.”

However, the Live Oak folks seem to want to relegate local music to the fringes. “Most of our ticketed shows will be all-ages shows and be over by midnight if not 11 –– if we can close down [after that] and reopen with a local band and no cover, we’ll do that,” said owner Bill Smith, whose son Casey Smith owns The Where House.

Simpson sees Live Oak’s awesome rooftop patio as a viable option for local artists. “We’re going to encourage local musicians to come up on the rooftop and jam out acoustically and have programs for young musicians to learn from what great local talent we have here,” he said.

Some local musicians think that if Live Oak wants to compete with Dallas concert venues, Bill Smith either will have to have very deep pockets or give more play to local artists. In focusing almost exclusively on mid-tier touring talent, Live Oak might find itself in bidding wars with multinational entertainment agencies. If, say, North Carolina’s supremely popular Avett Brothers play Dallas’ Palladium Ballroom, the big entertainment agency that booked them will forbid them to play within a 45-mile radius within a certain duration of time, usually a month or two. “The one thing that always stirred me up about [the big entertainment agencies] is that they all think Dallas and Fort Worth are the same city,” Liberio said. “The band can stay at the same hotel and play both shows and draw completely different people.”

Forella agreed, noting that he rarely bumps into Dallasites or Dentonites at Lola’s shows. “Nobody’s coming from Dallas and Denton,” he said. “They’re not driving to Fort Worth.”

With respect to a potential Granada West, Forella said, a person to keep your eye on is Maunder, who has plans in the works but isn’t ready to talk about them.

********

Things weren’t always this fertile. To assess the strength of today’s indie music scene, you’ve got to turn back the clock a few years to 1999, when the owners of a little hole in the wall on West 7th Street built a stage and installed a P.A. system.

Along with a pair of joints near TCU, The Wreck Room would eventually serve as one of the indie music hot spots for Fort Worth and as a classroom (albeit a graffiti-covered, smoke-filled, booze-drenched one) for the generation of musicians that rules today.

Fort Worth had independently minded, mostly underground rock ’n’ roll clubs before: The Cellar (downtown), Club Axis, The Impala, The Hop, Mad Hatter’s, the Ridglea, Caravan of Dreams. But a lot of the variables that have come together to help Fort Worth’s scene explode were not in play as recently as the late 1990s. Blogs were still in the future, and mainstream press coverage was spotty. For Fort Worth Star-Telegram critic Malcolm Mayhew, Fort Worth music was just one part of his beat. At Fort Worth Weekly, music coverage was also all over the map. A decade ago, about 90 percent of the bands on the Weekly’s annual Music Awards ballot were from Dallas and Denton. Granted, there was a pretty good explanation: Pre-9/11 Dallas was booming.

Deep Ellum was the epicenter, and while some of the great bands that played there were from elsewhere, even Fort Worth’s Flickerstick and The Toadies considered Deep Ellum home. Fort Worth was an afterthought.

But around the time The Wreck Room began hosting legit shows, an ad hoc group of some of the best singer-songwriters in town –– Brandin Lea (Flickerstick), Tim Locke (Calhoun), John Price, and Collin Herring –– began congregating one Sunday a month, first at The Aardvark and later at The Moon, both on West Berry Street, to swap songs as the Acoustic Mafia. The Weekly had already adopted its Tarrant County-only music editorial policy, and the long-running Good Show on The Choice (KTCU/88.7-FM) began opening its doors to in-studio performances, mostly by Fort Worth artists. Augmented slightly by the opening of what is now one of the longest-running all-ages DIY venues in the Southwest, 1919 Hemphill, a scene was slowly bubbling up. And it wasn’t all neat and proper. Some parties lasted until the next morning, some the entire next day.

While the Wreck Room regulars pretty much stayed put, undoubtedly mesmerized by the dimly lit club’s layers of red velvet, brass, and black paint, a lot of the Acoustic Mafia guys and their fans found their way to the Wreck. The West 7th foot traffic increased tenfold around 2003, when Wreck owner Forella opened an adjacent bar, The Torch, a glorious and fancily appointed den of vice where artists of all kinds and other blue-collar types drank ’til past last call, a great cross-section of Fort Worth sipped on martinis, and hot chicks danced (occasionally topless) on the bar with little provocation. To a youngster like Burning Hotels frontman Chance Morgan, Fort Worth was a rock ’n’ roll wonderland, from Berry to West 7th.

“Going to bars when you’re 18? That’s the coolest thing ever,” Morgan said.

After about a year, the Acoustic Mafia had run its course, and while The Moon was still drawing people to Berry, the Wreck/Torch had become the center of the Fort Worth musical universe. On one side of the complex on any given night, an architect, a motorcycle mechanic, and a lawyer might be sharing cocktails with a TCU undergrad, his father, and a hair stylist, and on the other side, a cool band –– Sub Oslo, Doosu, The Feds, 1100 Springs, or Slow Roosevelt –– might be playing to a sweaty crowd of 150 or more.

“The Wreck Room was a crazy place that your parents don’t know you’re at,” Morgan said. “We were talking about it the other day, telling somebody who wasn’t familiar with what [the Wreck] was that it was literally the CBGB’s of the Southwest. The bands that would come down would be, like, ‘This place is craaazy.’ ”

There wasn’t much else open at night around the Wreck/Torch, just a 24-hour 7-Eleven next door (for smokes, gas, water, and late-night snacks) and across the street a lovable little ’70s-ski-lodge-looking dive, J&J’s Hideaway, known simply as “JJ’s” or “the Hideaway.” (Why has no West 7th bar revived JJ’s old olive-in-the-draft-beer bit?) “I couldn’t have been anywhere better than that,” Morgan recalled.

Wreck shows were booked by Melissa Kirkendall, a filmmaker (Teen A Go Go) who started out in the biz as a chef and rock-club owner (The Impala, The Engine Room, Mad Hatter’s). Though the Wreck skewed predominantly toward Dallas, the club was also the site of The Burning Hotels’ first performance. “I don’t remember the show as much as I do that you wrote the first HearSay about it,” Morgan said. “I was feeling a lot of pressure, like, we’ve already got this built-up thing. We’ve been written about before we even played our first show. So it was kind of nerve-wracking.”

The show was packed, and the band did not disappoint.

Morgan’s guide to the scene was Flickerstick’s Lea, who met Morgan after a Flick gig at Ridglea Theater and not long after the wrap-up of Bands on the Run, the notorious VH1 reality TV show that Flickerstick “won.” Morgan started out as a fan and soon became what is known in the industry as a stalker. “I would be around, carry cases, do whatever,” Morgan recalled.

Being around naturally charismatic figures such as Lea, Price, Herring, and Locke inspired Morgan and Hotels co-founder Matt Mooty, not necessarily to be wild (insane?) but probably the opposite. “It was just crazy and fun, and I feel like I got my wild times out of the way when I was young, but I’m glad I did,” Morgan said. “I still make a lot of mistakes and do stupid things, but I got to live it and see it early, so it’s not like I’m still reveling in that thing. It’s done”

Around that time, Morgan had begun writing songs with Mooty. With Flickerstick soundguy Mick Flair, who also played drums, the future Burning Hotels banged out a two-song demo. When Lea began putting together a side-project, The February Chorus, he called on Morgan to play guitar. After about a minute, Morgan left to pursue the Hotels with Mooty, drummer Wyatt Adams, and bassist Coby Queen, two other young scenesters.

The Hotels have accomplished a lot since their formation, receiving airplay on The Local Edge, recording an EP and two albums, including 2011’s highly praised Burning Hotels, and making a performance cameo on the 2010 ’tween summer flick Bandslam, starring Lisa Kudrow and Vanessa Hudgens.

Morgan said he always felt lucky to be friends with people like the Acoustic Mafia, even though he and his Hotels bandmates don’t party quite so heartily. “We’ve always tried to stay in the middle,” Morgan said. “We really never were big drug users. We like to party. We like to drink. We like to have fun, but, geez, those guys were fucking wild.”

“Those guys” –– the Acoustic Mafia –– were also really talented and were idolized. “I mean, [Burning Hotels are] really good live,” Morgan said. “We’re energetic. We put on great shows. But I don’t think even we have the ability to sit with an acoustic guitar in front of 50 people and make everybody close their eyes and listen the way those guys did. I don’t know a lot of people today who can do that.”

********

In any list of Fort Worth bands poised for national success, Burning Hotels are likely to be near the top. Calhoun’s Roberts believes that a breakthrough for one band will benefit everyone.

“It’s like The Eye of Sauron,” he said, referencing Lord of the Rings. “When it sees Frodo, Samwise is lit up too. If Burning Hotels are Frodo, then the rest of us are Samwise. It’s like, ‘Hey, we’re here too!’

“It would be great if a band blew up,” he continued, “and then people would swoop in [and say], ‘Oh, what’s going on in Fort Worth? What’s this sound we have down here?’ And then it takes off from there.”

However, Roberts is convinced that there’s an anti-Fort Worth bias at work. He and bandmate Locke believe one of the best albums of the past five years came from Fort Worth –– but nobody noticed.

“I can’t believe [The Orbans’] When We Were Wild was not a national thing,” Locke said.

Roberts also questions why some big label hasn’t scooped up The Orbans. “I don’t get it,” he said. “It’s like there’s this weird bubble around North Texas, and it’s like people have this preconceived notion about what we’re doing down here –– ‘Oh, it can’t be that good; that place is known for shit-kickers and country music and intolerance’ –– even if it is good.”

There are plenty of other Fort Worth bands on that ready-for-prime-time list, including The Orbans, Calhoun, Fungi Girls, Telegraph Canyon, Green River Ordinance, Quaker City Night Hawks, The Hanna Barbarians, Pinkish Black (originally The Great Tyrant), and The Phuss. Most of them formed around the tail end of the Wreck/Torch glory days. “All the bands that are current now were all starting at the very same time,” said drummer Matt Mabe (Quaker City Night Hawks, Stella Rose, Jefferson Colby, EPIC RUINS, Big Mike’s Box of Rock).

Not long after the formation of his first band, Stella Rose, Mabe went to The Aardvark to see The Burning Hotels’ second show. “There were about 40 people there, and I fucking loved it,” he said.

After the show, he introduced himself to the band members; they’ve all been friends ever since. “We met [Lea] and all those dudes, and we just got sucked into it,” Mabe remembered. “It was awesome. It was a really good time.”

Mabe quickly got turned on to other relatively new bands, particularly Black Tie Dynasty, Lifters (now The Orbans), and Calhoun, whose second album, an eponymous gem, is TCU grad Mabe’s “college soundtrack,” he said. “We were obsessed with Calhoun, and that record always brings back TCU memories when I listen to it.”

Calhoun wasn’t the only great album coming out of Fort Worth. Most were debuts, and many are now part of local musical history. Black Tie Dynasty’s Movements, The Theater Fire’s Everybody Has a Dark Side, and Tame … Tame & Quiet’s Tin Can Communicate were all revelatory not just for their content but also for their production value. Collin Herring’s ominously titled Avoiding the Circus, arranger/producer Marcus Lawyer’s crowd-sourced album …shhh, Stella Rose’s Starving, Hysterical, Naked, and The Me-Thinks’ Make Mine a Double EP are a few other albums released around the time that hold up more than OK today.

Halfway through the first decade of the new millennium, the Dallas bands that normally packed The Wreck Room started disappearing. “They were playing Dallas more, started having kids,” Forella remembered. “But all the Fort Worth bands that are big now –– they’ve either stayed together or reincarnated into something else –– were the infusion that kind of changed everything.”

The scene also relied on radio-friendly heavies Goodwin, punk-ska rockers Darth Vato, the poppy cut*off, garage-rockers Voigt, and Lea’s February Chorus.

Some regular outdoor concerts and festivals also started popping up. The Weekly began producing a couple of them, including the annual Music Awards Festival, a free daylong summer concert featuring nearly 50 bands from the 817, at multiple clubs within walking distance of one another. Berry Street wasn’t as lively as it had been, but The Moon, though small, was still getting some pretty good shows, local and otherwise. With the addition of some off-night residencies –– Stella Rose’s Stephen Beatty at The Red Goose, Wednesday-night jazz at The Moon, Confusatron at The Black Dog Tavern –– you could find solid, original, independent live music almost every night of the week.

********

The good bands quickly became hot properties. All of the main club owners –– Forella, The Moon’s Maunder, and The Aardvark’s Danny Weaver –– were friends, which helped suppress any competitiveness. “Bands started overplaying here and there, but we’d call each other and talk” to avoid double bookings, Forella recalled. “Dallas bands always used to say that was cool because Dallas was so cut-throat.”

Forella knew the end was near for the Wreck/Torch –– the building was razed in 2006 to make room for the urban development that’s come to define the entire neighborhood. He bought an existing business down the road, the old blues venue 6th Street Live (originally 6th Street Grill). On Jan. 1, 2007, Lola’s Saloon opened. A short while later, The Aardvark began focusing on quality barbecue and catering to big touring acts and mostly obscure locals, and longtime musician Cody Admire opened The Grotto, a former sandwich shop not far from Lola’s.

Over the next couple of years, the number of legitimate independent Fort Worth bands doubled, no doubt a result of the fresh buzz about Fort Worth. The nonprofit, adult-alternative, and local-music-noticing radio station KXT (KKXT/91.7-FM) debuted. Blogs such as We Shot JR and DFW.com went live and began taking notice of Fort Worth talent, and the Dallas Observer also began devoting column inches to bands west of Big D.

Bands that either debuted or got popular at the time include Telegraph Canyon, The Great Tyrant (now Pinkish Black), Holy Moly, the (partially Dallas-based) Dove Hunter, and Whiskey Folk Ramblers. Most of them are still together.

But to paraphrase Liberio, why are there so few venues devoted solely to original local rock?

********

Right now, only a few clubs — Lola’s, The Grotto, and The Where House (and for no-alcohol all-ages shows, 1919) — focus on original indie and underground music.

But there are definitely other places where you might bump into a solid original show: The Aardvark, a TCU institution; Magnolia Motor Lounge, a clean, comfortable, affordably priced bar/restaurant whose booking skews toward Americana and blues-rock; The Cellar, a longtime TCU-area haunt where some creative stuff has been happening, mostly on weekends; The Basement Bar, a Stockyards-located spot where some progressive shows have gone down; and The Wild Rooster, a newish Cultural District address that has the occasional progressive show but mostly sticks with Red Dirt, cover bands, and karaoke. There’s also Friday on the Green, a free outdoor monthly concert series put on by Fort Worth South Inc. and the Weekly but that, well, is only once a month and only during the warm seasons.

Hotels frontman Morgan’s perspective is even grimmer. “The only legitimate venue is Lola’s,” he said. “But I can say at the same time that while I love [Forella] and every bartender there, there are too many people [for big shows], and it’s hard to get a drink. But it’s the best venue in town, the only venue in town.”

On Saturday, June 2, Burning Hotels will play a show –– at The Wild Rooster. Morgan said he and his bandmates are trying to accumulate as much money as possible to go on tour. They have two weeks on the East Coast booked. “We can make enough money [at the Rooster] to help pay for gas and hotels,” he said.

Though Morgan, a full-time bartender, has devoted the past decade to Burning Hotels, he believes that his band never fully arrived until it became popular in Dallas, getting airplay on The Edge, getting press in the Observer, and headlining the Granada. Clearly, the Granada and the Rooster are two wildly different establishments. “I never wanted to play [the Rooster], but I’m picking up shifts there, and I like the people there,” Morgan said. “It makes sense. … This is a business.”

Playing more frequently is not an option. “I think you should limit yourself to playing an event, to a crowd, to a person who wants to see you,” he said. “If you spread out [your shows], you’re gonna get so many more people [at each show], and if you build a bill, even more.”

********

For about a year in the early oughts, a kind of informal radius clause existed, prohibiting popular Fort Worth artists from playing locally too often. “Nothing like that exists in Fort Worth today, but maybe it should,” Morgan said.

Forella has felt the squeeze from oversaturation. “These [musicians] are all my friends,” he said. “I wish ’em all well. … But we’re so used to having those bands on a regular basis, and then all of the sudden it was a struggle because they were playing Friday over here and then play your bar the next night. It was half the draw it was.”

All Fort Worth venues need “more butts in the seats,” said Jamie Kinser, who with husband Aaron Knight recently opened a booking agency and promotions company, Blackbox Presents. Some of Kinser’s ideas include cross-promoting with local businesses, putting on shows in nontraditional venues (school auditoriums, art galleries, drama theaters), and adopting a bring-a-buddy-to-a-show policy. “Simply put, if everyone involved with a band, venue, studio, or agency in Fort Worth spent one hour a month reaching out to the community, we’d see the scene grow like wildfire,” she said.

One band that gigged a lot is The Hanna Barbarians. But no longer. “We were playing too damn much,” said Barbs frontman Blake Parish. “If there’s a stage and if there’s more than just us there, I’m gonna do it, but the rest of the guys aren’t that way. I understand. You can’t over-saturate.”

Veteran musician (and regular Weekly contributor) Steve Steward (EPIC RUINS, Oil Boom, Kevin Aldridge & The Appraisers, ex-Darth Vato) sees a different kind of musician today. “We just kind of played anywhere for very little money, and now it seems that a lot of younger bands want to get paid what we should have been paid,” he said. “It’s like there’s not a lot of dues-paying with a lot of these younger bands that I’ve been seeing.”

Forella empathizes with musicians who are simply brimming with creativity and just want to play. “Them being musicians, they want to play a bunch,” he said. “That’s what you do.”

He believes that things are starting to settle down. “It’s kind of working out good now, because it’s getting to a good mix, where it’s not competitive or the same kind of music,” he said. “Everyone’s getting along famously now. All the musicians and bar owners support each other cross-genre. It’s all different music, but they all support each other.”

********

Musically speaking, Fort Worth is not now nor is it ever likely to be in the same league as New York City, Los Angeles, or Nashville (or, heck, even Seattle), but the town can rightfully take its place alongside such diamonds in the rough as Portland, Ore.; Raleigh-Durham, N.C.; and Athens, Ga.

Kinser believes Fort Worth differs from most cities its size –– in a good way. “Since I’ve been doing a lot of tour booking, I’ve been networking with lots of other music scenes,” she said. “We have 30 amazing bands compared to four in other cities. Our talent is just scary. … It is a very exciting place.”

There’s one thing that everybody seems to agree on: To become a world-class music city, Fort Worth needs a pedestrian-friendly neighborhood of independently owned rock clubs a la Deep Ellum circa the late-’90s. True, we have the West 7th corridor, Near South Side, and Sundance Square, but they all are severely short on stages for local, original indie music. “I think a centrally located [area] is very important,” said Calhoun frontman Locke. “Fort Worth is all spread out. … We have a lot of good bands here right now, a couple great venues that are always willing to open their doors to original music, but it’s really hard to fire up the kind of thing we all like … without a centrally located area. Everything now is a destination venue.”

Well, you say, Fort Worth has world-class museums, ballet, and classical music. Let the dirty hippies go make their racket someplace else. Fine, but without support for the entire creative class, your city runs the risk of becoming some Rust-Belt hell-hole, bereft of the young creative types who drive local economies by spending money, frequently on guitars and on watching other people play guitars.

Nearly 40 million Americans –– more than a third of our entire workforce –– create for a living. “In the future,” writes Richard Florida, The Atlantic senior editor and author of the definitive tome on the phenomenon, 2004’s The Rise of the Creative Class, creative types “will determine how the workplace is organized, what companies will prosper or go bankrupt, and even which cities will thrive or wither.”

Fort Worth has the best country music scene. I am proud to be a part of the Texas Country Music arena. Please check out my website. Also please help support the Ronald McDonald House Ft. Worth. Worthy awards 2015 for “The house that love built” by Sonny Burgess and myself.

http://www.rmhfw.org