When someone from the TransCanada company asked the Crawford family in 2008 about an easement to lay pipeline across their farm on the Texas bank of the Red River, the family wasn’t interested.

The Crawfords thought that would be the end of it, and why wouldn’t they? Twice before the family had been approached in a similar fashion by pipeline companies, and when the family said they didn’t want their Lamar County farm disturbed, the companies simply used another route.

But TransCanada wouldn’t do that. The firm, hired to move tar sands bitumen — a mix of sand, clay, and water saturated with an extremely dense petroleum — from Alberta, Canada, to the Houston refineries along what’s been dubbed the Keystone Pipeline XL, upped its offer on the easement a couple of times between 2008 and 2011 from $7,000 to $21,000. When the Crawfords continued to say they weren’t interested, TransCanada went ahead and condemned the land it wanted in September 2011.

Since then, the two parties have been in a legal wrestling match pitting the Crawfords — farm manager Julia Trigg Crawford, her younger brother and sister, and their dad — against a multinational billion-dollar corporation that claims the right to take, by eminent domain if necessary, any land they want to lay pipe on.

[pullquote_right]TransCanada has been involved in at least 89 eminent domain land seizures in Texas alone.[/pullquote_right] It’s the latest version of the David and Goliath story that has already affected thousands of Texans who’ve been steamrolled by the natural gas industry. But this version goes beyond the usual pipeline land-grabs, because it involves a company taking property years before it will obtain a permit to lay the pipe — a company that may not be in compliance with Texas law and therefore may not have the legal right to take anything.

Despite those questions, TransCanada has been involved in at least 89 eminent domain land seizures in Texas alone. The fight involves the issue of which government agency, if any, oversees pipeline companies and their use of eminent domain. Landowners are asking why there is nothing in state law to make a company show the need for a new pipeline before it is allowed to seize private lands — and why individual landowners are having to go to court to thrash out issues that they believe should be covered by state law and public policy.

It’s an issue that seems designed to make Texans, with their love of the land, stand up and shout for answers. But few have. Oil and gas companies, as well as the pipeline companies, generally get to do pretty much as they like here, and even the people who know they can fight also realize they have little chance against companies that can hire lawyers by the carload and drag out lawsuits for years.

In this state, pipeline companies have been turned down only once in more than a hundred years, in taking land by eminent domain. And perhaps the most difficult part of fighting the pipeline companies is that the moment they file to condemn your property through eminent domain, they are considered to own the easement that’s been condemned and have the right to begin laying pipe. That’s a tough hurdle even for a landowner with deep pockets.

The Crawfords are one of a handful of families trying to fight back. They simply don’t want any of their land used for an easement for a pipeline that could rupture and ruin Bois d’Arc Creek, one of their farm’s primary water sources. They don’t want the Caddo Indian artifacts that lie just beneath the surface disturbed. They don’t want to say “How high?” just because a company demands they jump for private profit. For the Crawfords, it’s not about getting a better financial settlement from TransCanada in exchange for allowing them to lay their pipe: It’s about principle.

It will be a tough battle, made even tougher by President Barack Obama’s March 22 promise to fast-track federal approval of the southern leg of the Keystone XL project, a 485-mile stretch from Cushing, Okla., to Port Arthur, with a lateral leg running to Houston’s oil refineries.

The Crawfords know they are in a battle that will be almost impossible to win. But they do have a couple of aces up their sleeves: The portion of the farm that TransCanada wants for an easement is loaded with federally protected Caddo Indian artifacts. And they have farm manager Julia Trigg Crawford, the public face of their fight.

“You never go into a game without knowing you’ve got a chance to win,” the former college hoop star said.

******

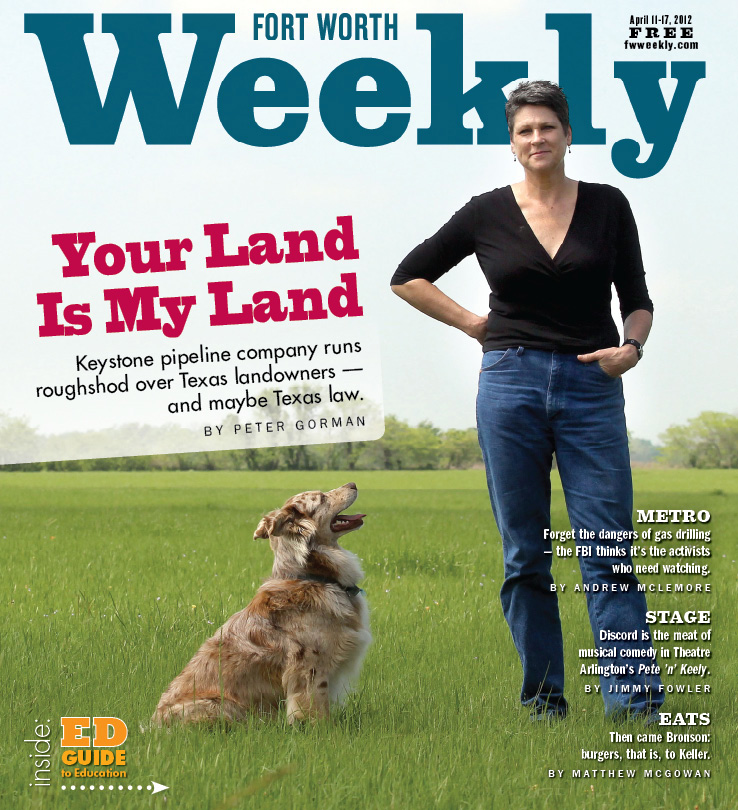

Tall, articulate, resolute, the 53-year-old Crawford says she never intended to become an activist. “But the tar sands issue and the issue of taking people’s land wasn’t getting the attention it deserved. So I went to Washington, D.C., and participated in the rolling two-week demonstrations on the issue last summer.”

The demonstrations were called to convince President Obama to deny permits for the 1,700-mile pipeline intended to run from Alberta to Houston, a pipeline that would exclusively carry tar sands bitumen.

In Washington, Crawford and 189 other people were arrested Sept. 1 for loitering in front of the White House. Police warned the crowd to move twice, and, when they didn’t, began to arrest people.

“We knew it was going to happen, we knew we were putting ourselves out there for a cause. Still, getting arrested as part of something like that was a very powerful experience for me,” said Crawford. “There were young people, retirees, grandmothers, all protesting the tar sands pipeline project. And the thing was that I understood that I had skin in the game. I was personally affected by the pipeline. But so many of the others were there just on principle, just to say no to the pipeline. That was humbling.”

With the arrests during that rolling demonstration, national media attention began to focus on the pipeline, she said, and some of that spotlight fell on her and the battle at the Red’Arc Farm.

At issue is an easement that would run the length of a 35- to 40-acre field on the southwest corner of the farm that encompasses about 650 acres. The field in question provides the Crawfords’ best grazing for their 32 Red Limousin cows and a Red Angus bull.

“It might seem that it’s just a little piece of land to most people, so why bother to fight,” Crawford said, “but to us it’s our land, and no one should have the right to simply come in and tell us they’re taking it so that they can make a profit. That doesn’t sit well with us.”

The family has a deep love for the farm. Julia Crawford’s grandfather bought it in 1948 and lived on it for years. Her parents moved onto it once Julia and her brother and sister were grown and worked it for 12 years. After his wife died, Julia’s dad moved to nearby Paris, but he still visits several times a week. Julia’s sister, Allison, has her own place that abuts the farm and raises goats and horses there. Julia spent time on the farm with her grandparents while growing up and moved onto it full time in 2010.

Over the years the Red River has changed course, eating away some of the original 700 acres, which is why she describes it as “650 or so” acres. Of that, 400 acres are leased out and farmed for soybean, wheat, and corn.

Even on the leased acres, Crawford is still responsible for turning on the irrigation system, checking the pumps, and occasionally running the combine. “I’m the farm manager, but I’m sort of a farm hand too,” she said. The other 250 acres include fields of hay, some woods, a small orchard, and space for the farm’s three horses to run. It is beautifully kept, with a couple of rolling hills and tall shade trees dotting the land.

Choosing to fight the pipeline company was a tough decision. “My dad, Richard Paul Crawford Jr., and my brother RP the Third, and my sister Allison and I sat around the kitchen table and talked about it. We knew it was going to cost us money we didn’t have, but we just decided it was the right thing to do. We also decided that no matter how much money TransCanada might finally offer, we were going to fight.”

[pullquote_left]“When you research and discover that these companies have no oversight, by anyone, well, that takes the wind out of you,” she said. [/pullquote_left]Crawford said the battle is a 24-hour-a-day job, most of it on her shoulders. She’s strong enough to handle it, having grown up on farms as her dad moved around the country to teach and practice as a veterinarian. They moved from Opelika, Ala., where her dad taught at Auburn University and where she was born, to St. Paul, Minn., then to Iowa City, Iowa, and other places, following his teaching jobs. Julia attended Texas A&M University, where she played forward for four years — her senior year as co-captain — on the then-fledgling women’s basketball team. When she finished school she went to work in the cut-throat corporate world as an executive recruiter in Houston, her career for 25 years before moving to the Red’Arc Farm.

While working in the corporate world helped shape the way she interacts with high-powered business people and attorneys, playing college ball helped shape the way Crawford approaches the current fight. “It doesn’t matter whether you’re playing an overpowering team or not. If you go out on that court and don’t think you have a chance to win, then you shouldn’t be out there. And that’s how my family and I feel about the pipeline. We’re not fighting this to lose. We’re fighting to win.”

But TransCanada is a formidable foe, and learning the ins and outs of the pipeline business has been a grueling task. “When you research and discover that these companies have no oversight, by anyone, well, that takes the wind out of you,” she said.

If she were to open a hairdressing shop, Crawford said, “there would be someone from the Texas Cosmetology Commission or whatever out there to check my credentials the next day. But that’s not how it works with pipeline companies. They simply file paperwork with the Texas Railroad Commission, and if it’s filed properly they get their permits and start condemning private property. No agency has the responsibility to check on what they’re doing. The responsibility of the Railroad Commission stops at the moment they hand out those permits.

“Which leaves it up to the landowner to push back,” she said. “And unless you do … well, a pipeline company in Texas can get away with a lot.”

Among the things a pipeline company can get away with is taking private property by eminent domain even before it has the permits to build the line. Those permits include the U.S. Army Corps of Engineer water crossing permits, which involve investigating how the pipeline might affect local water sources. Additionally, hydrostatic testing permits — permits to use local public water sources to fill the pipeline to test its strength — must be issued by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, but the agency has temporarily quit issuing such permits due to last year’s dire drought conditions. TransCanada can get around the need for the TCEQ permit if the company can find sufficient private water sources.

“You have to look at it this way,” said James Bradbury, a Fort Worth attorney who specializes in eminent domain cases and who worked on both gas well ordinance committees during Mayor Mike Moncrief’s tenure. “The pipeline industry is the only industry in the United States where their largest asset is their ability to take private land for personal profit. It’s as simple as that.”

******

Private pipeline companies technically do not have the right to utilize eminent domain. That is reserved for what are called “common carriers,” companies that advertise to the public that their pipelines are available to carry petroleum products for any producer, first come, first served, for a published fee. Companies that meet those basic requirements are considered public utilities and therefore have the same rights to acquire private land as a utility company does.

But all that’s required for a company to obtain eminent domain power is a check mark in a box on a form, stating that the firm will become a common carrier. After that it’s up to a landowner to challenge that status if they want to fight a condemnation proceeding.

Not everyone thinks the southern leg of the Keystone XL pipeline fits those requirements. Among those who question that is Debra Medina, a libertarian-leaning Republican activist who in 2010 lost to Rick Perry in the Republican gubernatorial primary. Shortly after that loss she started WeTexans, a “nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that fights to protect liberty, integrity, and justice through education and legislation.”

Medina said that current Texas law allows for seven products to be moved through common-carrier pipelines. “Those products range from natural gas and light crude to heavy crude and coal,” she said. “But the question is whether bitumen, which is what’s being moved when you move tar sands, is one of those seven products that allow you to be considered a common carrier.”

She pointed out that Enbridge, another Canadian pipeline company that moves tar sands bitumen, argued in United States federal court that it shouldn’t have to pay an excise tax levied on oil pipelines because what Enbridge’s line carries isn’t petroleum. Income from the excise tax pays for the cleanup of oil spills.

“Now if Enbridge is allowed to argue that their product is not crude oil and therefore they do not need to pay into the cleanup fund, how is it that TransCanada, planning on moving the same material, can claim that they are moving crude oil and therefore have the right to acquire land through eminent domain?” Medina asked.

Enbridge was responsible for an 820,000-gallon spill of tar sands bitumen in Michigan that found its way into a 40-mile stretch of the Kalamazoo River watershed — a spill that has been thus far impossible to clean up because the heavy bitumen has settled into the sediment at the bottom of the river. The EPA initially thought it would take a year to clean the 2010 spill, but by 2011 had revised that estimate to “several years,” and still cannot provide a date when the cleanup will be completed.

Tar sands bitumen, which will be the primary product carried from Oklahoma to South Texas by the Keystone XL pipeline, is nearly solid at room temperature. To make it light enough to flow through pipelines, natural gas liquids are pumped into it, turning it into a sludge that can still be moved only under extremely high pressure. According to the National Resources Defense Council, the pressure is necessary because the sludge “is between 50 and 70 times as thick as conventional crude oil.”

There is a second reason why TransCanada’s Cushing-to-Texas pipeline might not meet the criteria for common carrier status, Medina said. “I think there is a big legal question of how this is going to be a ‘for the public to hire’ pipeline in Texas when there will be no point of entry for any Texas petroleum products in the entire length of the line.”

Trevor Lovell of Public Citizen, a national nonprofit consumer advocacy group, agreed. “In Texas, if you’re going to utilize eminent domain, you’re supposed to have Texas product in that line. But by contract the new line will be taking primarily tar sands bitumen from the Keystone One line that was completed in 2010, and then it can take some product from the on-ramp at Cushing. But there is no other on-ramp for that line, so no Texas product will be moved.

“Certainly that is an argument that Julia Trigg Crawford can use in fighting the eminent domain on her farm,” Lovell said. “And she can also use the argument that while bitumen is a hydrocarbon, it is not a petroleum product, and the carrier therefore has no right to be classified a common carrier with eminent domain rights in Texas.”

Lovell and Medina are just two of the allies Crawford has picked up in her ongoing battle. Another is the Caddo Nation, which has a key historical site on the land abutting the Crawfords’, a site that spills over into the pasture where TransCanada wants to lay pipe.

Known as the T.M. Sanders site, it includes a Caddo village and ceremonial center dating back to about 1100 A.D. On Feb. 28, Robert Cast, historic preservation officer for the Caddo Nation, wrote to the chairman of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation — an independent federal agency that advises the president and Congress on historic preservation policy — noting that since 2009, the Caddo Nation has been requesting a government-to-government consultation with the U.S. Department of State “with respect to the impacts of the Keystone XL pipeline with respect to places of importance to us.”

In the letter, Cast wrote that the Sanders site has been archaeologically investigated since 1931 and that any incursion onto the Crawford farm will put valuable historical artifacts in “imminent peril.”

[pullquote_left]…when pipeline companies say they need eminent domain to lay pipe for the public good, we have no process to investigate whether that pipeline is actually needed. [/pullquote_left]TransCanada, which did not answer Fort Worth Weekly’s requests for comment, has acknowledged the importance of the Sanders site. On two occasions it sent out archaeologists who discovered important artifacts just beneath the surface of the Crawfords’ pasture. Those findings led the company to alter the course of the proposed pipeline to another section of the field, where the archaeologists said they found no artifacts.

But Crawford wasn’t satisfied and brought in her own archeological specialist last October to inspect the new proposed easement site. “They did 15 shovel tests — where you just dig with a shovel into the ground and then see what you find — and five of them came up with artifacts,” she said.

Armed with that information and thinking that TransCanada might begin trenching her field at any moment, Julia asked the county court at law in Paris for a temporary restraining order against the pipeline company. It was granted on Feb. 13, but dissolved on Feb. 24 after a hearing before Judge Bill Harris.

TransCanada lawyer James Freeman told Harris, “We are not going to have one landowner hold up a multibillion-dollar project that is going to be for the benefit of the public. That is my whole argument.” But Freeman went on to point out that TransCanada legally had possession of the Crawford’s land the moment it was condemned, so the Crawfords had no right to restrain them from doing what they wanted with it.

“I thought that was strange,” said Crawford, “because they had told us they didn’t have possession of the land at other times. But then they said they did when it suited their purpose.”

TransCanada threw another curve when Freeman told Harris the company was planning to bore a hole for the pipeline well below any Caddo artifacts.

“When their attorney said that, he stood up and showed a picture of the planned horizontal drilling,” Crawford said. “But he never entered that into the court record. And they’ve never mentioned it before or since. Everything they’ve discussed with us involves trenching, which is much less expensive than drilling.”

When the question was raised concerning what material TransCanada would move through the pipeline that would make it a common carrier under Texas law, Freeman said the company was not required to present that information until the pipeline was in operation.

Once she lost the TRO fight, Crawford said, “I began to wake up every morning thinking that I would look out the window and see machines trenching the land.” That has not happened yet, “and I don’t know why it hasn’t,” she said.

“It might just be that they would prefer for this to be quiet for the moment rather than loud,” said Crawford. “And it would get loud, with a lot of press, if they just came in here and started digging before the case is settled.”

******

Crawford said TransCanada has consistently told her family that everyone along the pipeline route has voluntarily sold rights to easements the company wanted on their property — including when Freeman referred in court to “one landowner” holding up the project.

But Debra Medina said the picture painted by TransCanada is not accurate.

“I was in Delta County, one of the counties affected by this pipeline, and I asked the county attorney if he was aware of any condemnations in his county related to it,” she recounted. “He told me he didn’t think there were any. So I went to the district clerk’s office in the Delta County courthouse and asked them to check the records of any cases where TransCanada or Keystone was a plaintiff. And I was handed a file with six cases in it.”

Since then, Medina has gotten condemnation records from 14 of the 18 Texas counties affected by the southern leg of the Keystone XL. “So far I’ve come up with 89 condemnations in the 14 counties I have,” she said. “And that doesn’t square up with how they’re saying few people are contesting the taking of their property. I mean, the story that TransCanada is painting in Texas is not what it really is. There is one condemnation in every four miles, and then there are those who settled under duress. When someone is holding eminent domain over your head, there is no way to consider that a fair or voluntary agreement.”

Bradbury, the Fort Worth attorney, said TransCanada “has been condemning property on that pipeline for years. It’s a sort of Joseph Heller meets Franz Kafka conundrum. They condemn your land, and then you have to prove the company is not a common carrier. And that’s only happened once that anyone can remember.”

In that case, Texas Rice Land Partners Ltd. and Mike Latta vs. Denbury Green Pipeline-Texas LLC, the Texas Supreme Court ruled in August 2011 that because the pipeline company planned to exclusively move its own product from a mining operation to its own installation, it was not a common carrier and therefore had no eminent domain rights (“Down the Pipe,” Nov. 30, 2011).

“I just don’t know whether the law is clear enough on common carriers,” said Medina. “I want the legislators to look into what constitutes a common carrier. And the legislature says they will bring this up in the House Land and Resource Management Committee in special session in June. But that’s probably going to be too late to help the Crawfords or any of the other 89 people on the pipeline.”

[pullquote_right]“With every other type of work, from road building to school building, there is an authority that oversees things, someone with regulatory oversight power,” she said. “But there is no one with regulatory power over the pipeline companies’ use of eminent domain. [/pullquote_right]One key point that Bradbury thinks has been overlooked is that “when pipeline companies say they need eminent domain to lay pipe for the public good, we have no process to investigate whether that pipeline is actually needed. We all think that the only pipelines being built are those that are necessary, but there is nothing in place to evaluate that need.”

In Bradbury’s opinion, if the United States really needs the Canadian tar sands bitumen that the Keystone pipeline will deliver, “the Julia Trigg Crawfords of the world ought to have a forum where that can be demonstrated. We need more checks in place than that.”

Terri Hall, founder of Texans Uniting for Reform and Freedom and a ferocious advocate for property rights, is furious about the way TransCanada has been handling property acquisition.

“People got in touch with me about this pipeline back in 2008 to ask how TransCanada had the power of eminent domain without the pipeline even being approved or permitted. And you know that the answer is that all that company has to do it walk into the Railroad Commission, fill out a one-page application, and they’re approved, with eminent domain authority.”

Hall said she’s spoken with homeowners, ranchers, and farmers who have been confronted by TransCanada and other pipeline companies and “their armies of attorneys.” Most people don’t even know they can challenge the authority of those companies, she said. “And even if they do, who the heck has the money to go up against billion-dollar companies?”

Hall’s primary fight has been against the condemnations planned for the now mostly defunct Trans-Texas Corridor. But she sees a lot of similarities between that roadway system and the fast-tracked pipeline.

“Look, to have a private company come in and have the right to take your land so that they can make money moving a foreign product across the United States, across Texas to be sold to other foreign countries, is just unbelievable,” she said. “This has nothing to do with bringing oil to the U.S. to ease our dependence on Middle Eastern oil.”

Hall said she has yet to speak with one Texan who likes the idea of eminent domain used in this case — and, she notes, that includes people who support the pipeline. “With every other type of work, from road building to school building, there is an authority that oversees things, someone with regulatory oversight power,” she said. “But there is no one with regulatory power over the pipeline companies’ use of eminent domain. Eminent domain for private gain is alive and well in Texas.”

******

The Crawford family isn’t wealthy, but they do have a number of supporters who have been contributing to their defense fund via the standwithjulia.com website.

Crawford said she has been surprised and delighted at the public’s response to her family’s situation. “I’m amazed at the generosity of people I will never meet who are sending us their hard-earned dollars to help fight this fight,” she said. “Not knowing if we’re going to win, but just to keep us in the fight.”

Following the dissolution of the original TRO, the Crawfords took their case to the state appellate court in Texarkana, which granted a second TRO on March 3. That, too, was dissolved, a week after it was issued.

The case will now go to trial on the merits in county court at law in Paris. The initial trial date of April 30 could be pushed back to late May or June, Crawford said. The Crawfords and their attorneys are considering asking that the case be divided into two proceedings.

“One would be a jury trial over the value of the land that was condemned,” Crawford said. “TransCanada valued the land as purely agricultural. But my dad had an idea that we could sell five- or 10-acre tracts of that pasture if we ever needed to raise money for the farm. And anything that would be built would be built with the assistance of archaeologists to make certain no artifacts were disturbed. So we want the land revalued, and we’ll present a jury with evidence of that value.”

The second element of the case, to be decided by Judge Harris, would deal with the archaeological importance of the easement in question and whether TransCanada’s pipeline meets the criteria of a common carrier.

Medina said TransCanada is working hard to get some West Texas crude to Cushing so that the line will be carrying some Texas product and thereby qualify as a common carrier.

Asked whether they would sell the easement if TransCanada came up with a huge offer, Crawford said the family is united in wanting to see the court case through.

“And you know what? No matter where this thing winds up I will hold my head up high,” she said. “Even people who disagree with me have been respectful of my willingness to stand up for this cause.”

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know so much about this, like you wrote the book

in it or something. I think that you could do with some pics

to drive the message home a little bit, but other than that, this

is wonderful blog. An excellent read. I will certainly be

back.

We have an appt on Monday, October 6, 2014 with a “land man” from North Carolina wanting to give us ingress and egress to our property and doesn’t “own” any property down in Liberty County. After my dad passed away and left me and my sisters 66 acres in Liberty County, we looked it up on Google map since we live in Houston. It appeared that timberland was being cut down in our “thicket” of trees mainly used for hunting back when my dad was younger. So my husband and I rode down there (about an hour trip) and another landowner showed us where our property was and showed us a pipeline going across the southeast corner and there were back hoes and bulldozers ripping up the land. We tried to contact Liberty County about this and got nowhere. So we dropped it for the time being because we had other things going on. Anyway, we just received this letter from an NC land company telling us what they wanted to do, but wouldn’t tell us why –we have our suspicions so we are meeting with him Monday instead of just signing the documents. Should we get an official of our own to go with us to make sure he is telling us the truth?

Hi to every body, it’s my first pay a quick visit of this website;

this blog carries awesome andd in fact excellent stuff in favor of visitors.