John Storm was introduced to Fort Worth Weekly readers several years ago when film writer Kristian Lin described the new leadership at the Lone Star Film Society (“Lone Star In Focus,” Dec. 31, 2008). Storm, the managing director, was described as energetic, passionate, and highly organized. The Army and Air Force veteran hailed from Dallas but said he “fell in love with Fort Worth” while stationed at Carswell Air Force Base from 2005 to 2007.

Storm vowed to apply his logistical skills to create a better business model for the nonprofit that puts on the annual Lone Star International Film Festival. But he also admired movies as art, citing They Came To Play, a documentary about the 2007 Van Cliburn amateur piano competition. He’d recently shown the movie to a group of school kids.

“These were inner-city kids who had little exposure to classical music, and they were totally quiet while they were watching,” he told Lin. “When it was over, they had all these questions about the Cliburn. Film can be a powerful gateway to the other arts.”

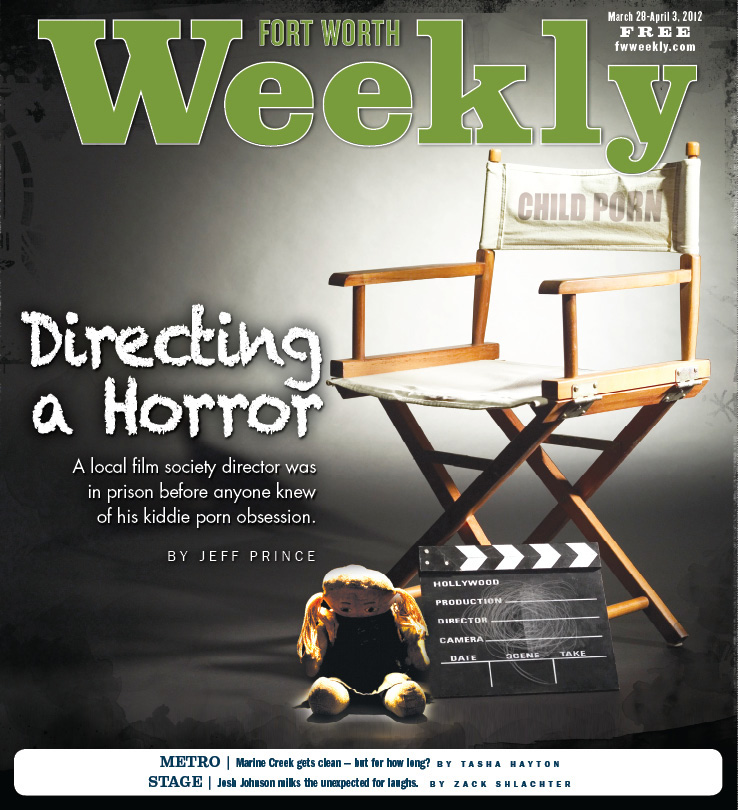

Children and media would lead to Storm’s downfall. He’s now sitting in a Texas prison, convicted of possessing child pornography and directing the sexual performance of a child under 14. The latter charge is a first-degree felony punishable by up to 99 years in prison. Storm pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 10 years in prison, but he could be freed in less than two and serve out the remainder of his sentence under probation.

[pullquote_right]Police said Storm logged onto an internet chat room in 2009 and talked via webcam to a man in Florida who was sexually abusing his young daughter while Storm watched and directed from his Benbrook apartment. [/pullquote_right]Storm resigned his position at Lone Star Film Society last summer without explanation or fanfare. He left a note and didn’t return. As it turns out, Storm’s life lived up to his self-chosen surname. He was in the eye of a tempest, accused of directing child pornography over the internet in a case so unusual that the prosecuting attorney was taken aback.

Police said Storm logged onto an internet chat room in 2009 and talked via webcam to a man in Florida who was sexually abusing his young daughter while Storm watched and directed from his Benbrook apartment.

“I’ve not seen a case where a guy was doing this,” assistant district attorney Marty Purselley said.

A police tip led to the Florida man’s arrest, and he in turn gave evidence on Storm. Benbrook police served a warrant on Storm in September 2010, and he was jailed, trotted through the justice system, and convicted in July 2011. Only then did he resign. Somehow, he’d managed to keep his criminal actions and prosecution hidden from friends, co-workers, and the media — even after he’d landed at the Texas prison system’s Gurney Unit in December.

Storm also served as a national committee member for Kids First!, a nonprofit coalition for quality children’s media. Kids First! continued to list Storm among its members until two weeks ago when the Weekly called to inquire about his involvement in that organization.

Director Ranny Levy was shocked to hear about Storm, who served with Kids First! in his role as director of Fort Worth’s film festival.

“Oh my god,” she said. “I’m just absolutely astonished. He totally dropped off our radar screen. He had been a great partner of ours and left, and nobody would tell us what happened to him.”

The Lone Star Film Society is keeping quiet. No announcement was made about Storm’s resignation or conviction, and nobody is eager to talk about it now. The film society is getting ready for the upcoming film festival in November, which requires drumming up donors, marketing the event, and attracting visitors and film people. Discussing a convicted sex offender in its ranks isn’t the best way to kick-start the event.

“We haven’t had any contact with John since July,” film society director Alec Jhangiani said. “He resigned at that time. Beyond that, I really can’t comment on anything personnel-related.”

Jhangiani and former artistic director Dennis Bishop were featured alongside Storm in our 2008 cover story. Now Bishop is senior advisor with the group, but he’s remaining tight-lipped as well.

“It’s not a good policy to talk about former employees,” he said.

He, Jhangiani, and film society board members referred questions to board chairman Johnny Langdon, who discussed the former employee somewhat reluctantly.

Storm declined to be interviewed at his prison cell at the Gurney Unit in Tennessee Colony, deep in the Piney Woods of East Texas.

********

The resignation letter that arrived on July 1, 2011, caught everyone at the film society by surprise. The letter simply stated that Storm was having “family problems” and would no longer be working at the film society and asked that nobody try to contact him.

“We had no idea where he was or what he was doing,” Langdon said.

“It was so abrupt that it made no sense,” said board member Ken Schaefer. “Consequently, that’s why people reached out to try to find out if he was OK.”

Employees tried calling Storm, but he didn’t respond. He still hasn’t talked to any co-workers or board members since quitting, Langdon said.

It wasn’t until December, when Storm was sent to prison, that co-workers discovered what had happened — and only after someone called the office to tell them, Langdon said.

“Everybody was very surprised,” he said. “He’d be the last person in the world anybody believed would be involved in something untoward.”

“It never entered any of our minds that, my gosh, maybe he is in jail,” Schaefer said.

Acquaintances describe Storm, now 37, as a gung-ho go-getter. Local filmmaker James Johnston met him shortly after Storm’s arrival at the film society and found him to be passionate about films, filmmakers, and business.

“He was a motivator, very driven, very organized. Not necessarily the creative drive around the Lone Star, but very driven,” Johnston said. “Everything about his personality made sense that he came from that military background. He seemed very disciplined and left-brained. He was always very nice and positive and interested in whatever I was doing.”

Johnston, like many people contacted for this story, knew that Storm had resigned from the film society but had no idea about his crime.

Honorary board member Phillip Crow said Storm’s actions shouldn’t tarnish the film society. If it were his decision, Crow said, the film society would “simply come out and say something, get out in front of it, and say this has nothing to do with who we are or what we represent.”

Now some board members wonder why they weren’t told about Storm’s conviction before a reporter called. “I would have appreciated a heads-up on all this,” said Tom Copeland, Lone Star board member and former director of the Texas Film Commission. “To hear about it from you is kind of a shock.”

But film society leaders never did that. They said police never contacted them about the case, and they still don’t know any specifics.

Storm didn’t seem to fit the criteria for a sexual deviant. The divorced father was confident, conservative, industrious, and living with an attractive girlfriend. (Storm has a young son from a previous relationship but did not have custody of the child.)

“You could blow me over with a feather,” Copeland said as he digested the news. “John always seemed to be such a straight business person … and seemed like a much more ultra-conservative person compared to the other people in the film industry. Nobody ever told me why [he left]. I thought a lot of John, I really did. I didn’t know him that well, but he seemed like such a straight arrow.”

The film society hired Storm in August 2007 to replace outgoing managing director Tom Huckabee, whose contract had expired. Langdon said he located Storm through an employee search firm.

Storm had earned a bachelor of arts degree in marketing at the University of North Texas in 1998 and enlisted in the Army the following year. He said he wanted to serve his country while simultaneously repaying his UNT student loan.

“From his resumé to his background check, there were no red flags raised whatsoever,” Langdon said. “John Storm worked for two presidents. He was vetted by the White House twice.”

The National Archives provides limited information about veterans’ military records. However, Storm was mentioned a few times in Fighter Line, an Air Force Reserve publication at Carswell Air Force Base. Based mostly on his accounts, Storm served in the Army until 2004 and was part of the Third U.S. Infantry’s “Old Guard” that escorts presidents.

His ex-wife — they began dating in 2000 and were married from 2003 to 2005 — confirmed Storm’s service and described him as a dedicated military man. As a noncommissioned officer stationed in Washington, D.C., he was on escort duty with presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. His ex-wife said he was homesick for North Texas after his Army enlistment ended. He earned his master’s degree in business management at Troy University in Alabama in 2005 and then joined the Air Force Reserve and was stationed at Carswell as an intelligence officer.

The Feb. 3, 2007, edition of Fighter Line contains a story under the headline “Stripes To Bars Gives Enlisted Time To Shine,” with a photo of Storm receiving his officer bars after being promoted to the rank of second lieutenant. The story, written by Staff Sgt. Kristin Mack, describes how Storm received the “highest score ever” upon graduating from the Air Force’s six-week Academy of Military Science program, which trains individuals to become officers. Storm prided himself on his physical fitness and devotion to duty and told Mack about helping after the 9/11 Pentagon attack, pulling the first U.S. flag from the rubble.

“The experience was life-changing,” Storm told the reporter. “It made me aware of my blessings and freedom.”

Storm was deployed to Iraq in 2005 and volunteered for a second deployment, according to the Fighter Line story. “He always volunteered to help where help was needed,” Senior Master Sgt. James Hunt said in the story. “He is meticulous and stays focused on the mission.”

Another officer described Storm as exceeding expectations and producing results. “We are lucky to have him,” Col. Bruce Cox is quoted as saying.

The story ends with some humble words from Storm: It “is important to live in service to other people; this is my opportunity to give back.”

Storm appeared to be a rising star, but if so, it was one that fell rapidly. Shortly after the Fighter Line article appeared, Storm was gone. Details about why he left the Air Force are unclear, although his ex-wife, who requested that her name not be used in this article, said she witnessed him selling stolen merchandise on eBay while they were married in 2005. She said that he sold cameras stolen from a retail store truck and merchandise stolen at Carswell.

Storm’s ex-wife saw firsthand that Storm was into computer sex. They began dating in 2000 while he was in the Army and stationed in her home state of Virginia.

“Back then he was very charming, very sweet,” she said.

She caught him engaging in internet sex talk with other women in 2001 and broke up with him, but he spent many months wooing her back and promising fidelity. They married in 2003, but she soon suspected he was establishing online relationships again. While Storm was deployed in Iraq, she went through his things at home and discovered pornographic magazines, including a couple that featured only prepubescent girls.

“That was a key indicator that something wasn’t right,” she said.

She left him and filed for divorce. Storm didn’t show up for the court proceedings, she said.

“The last time he tried to contact me was a couple of years ago, and I said, ‘Why are you contacting me? Leave me alone.’ That was the last I heard from him,” she said.

She sees irony in the fact that he changed his name from John Lackey to John Storm in the years before they met. Storm disliked his original surname because he disliked his biological father. He said in court during his sentencing that his father was physically and emotionally abusive to him as a child. To shake himself of his past, Storm changed his name when he became an adult.

“He wanted a strong name,” his ex-wife said.

[quote]“That was a 6-year-old girl who was getting molested partly because this guy (Storm) was directing it,” the prosecutor said recently. [/quote] After their divorce, Storm’s ex-wife received an e-mail from a woman who said she was Storm’s girlfriend and the mother of his young son. She too was having trust issues with Storm and wanted to share notes.

“She told me he was caught stealing and discharged from the Air Force,” the ex-wife said. Military records could not be obtained to verify that.

Storm landed his job at the film society in August 2007 and quickly began impressing people with his work ethic.

“He was an exemplary employee while he was here,” Langdon said. “He’s a very straitlaced guy with a military mind-set. He did everything we expected him to do. He was a really good employee.”

Now, co-workers and most board members are distancing themselves from Storm.

“Nobody wants to say anything that gets put in print and reflects badly on the film society,” Langdon said.

No public announcements were made about Storm’s departure in July nor about his incarceration in December.

“This was an ex-employee that we hadn’t seen in eight months,” Langdon said. “It’s not up to the society to say what happened to employees. We don’t comment on personnel matters, period.”

The society had used a Fort Worth employment service as a headhunter, and the company provided Storm’s resumé in November 2007. He’d passed a background check and drug test and provided an impressive list of accomplishments.

“When you hire somebody through a headhunting company and they do a background check, especially with a resumé like this, we don’t have anything to apologize for,” Langdon said. “He was a very nice guy and a hard worker and a dedicated guy.”

About five months passed after Storm resigned before co-workers heard about his conviction for directing and possessing child pornography. “Somebody called us,” Langdon said. “Everybody was stunned.”

The astonishment is spreading. Storm produced the 2009 AFI Dallas International Film Festival (he also served as an event producer at the 2010 event). Now the Dallas Film Society is distancing itself and refusing to comment on Storm.

He was also an advisory board member at the Asian Film Festival of Dallas.

“We haven’t heard from him in a while, and I understand that nobody knows where he is,” said Executive Director Alicia Chang.

When told that Storm was in prison, Chang was incredulous.

“We asked him to be on our board because we wanted someone who works at another film festival and had really strong knowledge of operational issues,” she said. “He was always very helpful and gave us great ideas and great contacts on who could help us on things that concerned the festival.”

********

Storm gave his resignation letter to the film society on the same day he appeared at a sentencing hearing in District Judge George Gallagher’s court — on July 1, 2011. But the seeds of Storm’s downfall had been planted almost two years earlier on that internet chat room.

The Florida Department of Law Enforcement received a tip that a Lake City man was sexually abusing his 6-year-old daughter on a video chat room. Police identified the man and arrested him on Sept. 24, 2009. Michael Duane McMillan told police that he corresponded with a man in Benbrook during chat room sessions. McMillan told police that the man, using the name Davidoff1200, would direct him on how to sexually abuse his daughter as the man watched on the webcam.

Florida officers confiscated McMillan’s computer and kept up the correspondence with Storm, under McMillan’s user name. They exchanged explicit sexual banter about young girls, and “Noleboy7” invited Davidoff1200 to come to Florida to participate in the sexual abuse. Davidoff1200 sounded interested but didn’t take the bait.

Florida police notified the Tarrant County district attorney’s office. Benbrook police arrested Storm at the home where he’d been living while stationed at Carswell. DA’s office investigators recovered child pornography from Storm’s computer and confronted him with McMillan’s claims that he had directed sexual abuse on a webcam. They revealed that Florida police had been posing as “Noleboy7.”

Storm admitted his involvement, saying he was ashamed and wanted help.

Judge Gallagher said recently he’d never seen a similar case involving coordinated child molestation with two adults in different states using webcams. The judge handed down a 10-year sentence. But he’d decided that Storm was a good candidate for “shock probation,” which involves sentencing criminals to prison stints and then bringing them back to court after a few months, and, if they have had no problems in prison, reducing their sentences. The hope is that prisoners without a criminal history will be shocked by incarceration and be scared straight.

Gallagher brought Storm back to the courtroom in December and reduced his sentence to two years with 10 years probation. He could be paroled at any time.

“He was a great candidate for probation, but the facts of the offense had to be taken into account,” Gallagher said. “He had no criminal history of any sort.”

A short stint in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice system might set Storm straight, Gallagher said, but probation means he’ll be supervised and monitored as a sex offender for years after his release.

“You hope to kind of shock the person into seeing what prison is like,” he said.

Gallagher said Storm has proven to be a model prisoner and is eager to try and get his life on track.

Purselley isn’t as forgiving. The prosecutor questioned the judge’s optimism and the less-than-severe sentence he handed down. He pointed to the large amount of child pornography found on Storm’s computer. And Purselley wasn’t convinced that Storm has fully accepted responsibility for his actions.

“That was a 6-year-old girl who was getting molested partly because this guy was directing it,” the prosecutor said recently. “I don’t have much patience or sympathy for a guy like this. He tended to minimize [his involvement]. That’s self-preservation. There was a certain amount of detachment in there.”

Purselley’s frustration showed in the court transcript when he cross-examined Storm and asked about his attraction to child pornography. Storm said he was addicted to sex in general and not just under-age girls.

PURSELLEY: You talked about going down there to Florida to meet Noleboy7 and his daughter, didn’t you?

STORM: I never had any intention. He brought that up, and I was just placating.

PURSELLEY: And do you want to read the chat for your family so that everyone can hear how you’re talking about what you want to do to this little child? Is that necessary? Because you seem to be fighting me on this and minimizing this … .

STORM: No, sir.

PURSELLEY: … and saying that you’re not interested in kids.

Storm said he was interested in watching child pornography and discussing porn in chat rooms, but not in having actual physical contact with children.

PURSELLEY: And you were able to do all of this and lead what appears to be a really nice, normal life with a beautiful woman?

STORM: On the surface, yes, sir.

He sought psychiatric help through the Veterans Administration after his arrest in 2009, attended Sex Addicts Anonymous meetings, performed community service, admitted his involvement in child porn to his parents and girlfriend, expressed remorse, and had tried to rewire his brain, he said.

“I’m incredibly sorry for what I’ve done,” he said in court. “There is nothing I can do. Just beg forgiveness.”

Purselley still feels Storm downplayed his role in the molestation and deserved a longer prison stint. The U.S. Department of Justice cites a recidivism study that tracked almost 10,000 sex offenders for three years after they were released from prison in 1994. About 5 percent were re-arrested for sex crimes. The sex offenders were four times as likely as other former inmates to be re-arrested. Other studies have also cited higher rates of re-arrest for sex offenders and shown that most sex offenses go unreported.

“This is an individual who would deserve every bit of justice the system could give him,” Purselley said.