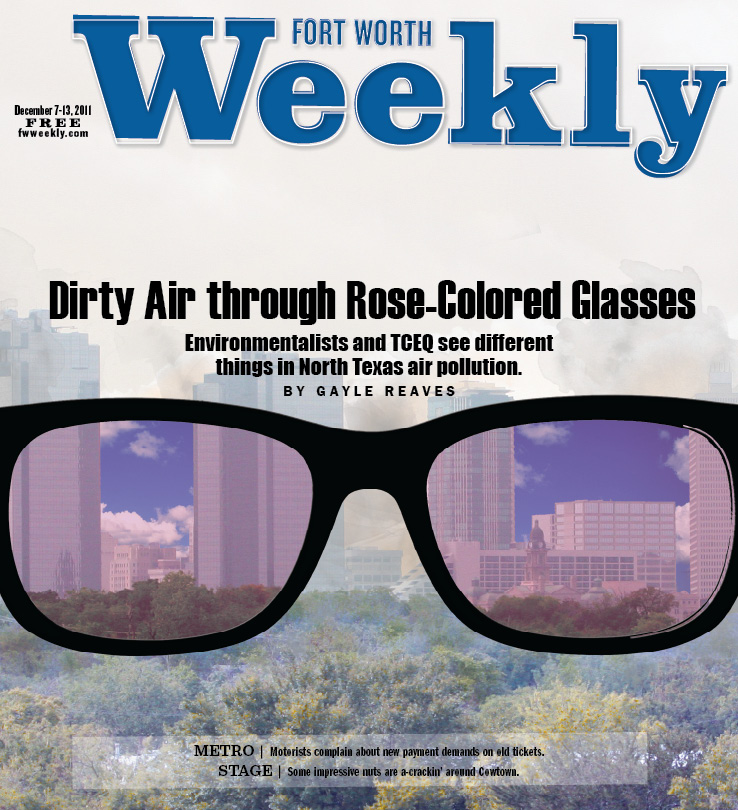

North Texas has been struggling for years with dirty air. Last year, it moved up in the Environmental Protection Agency’s classification of smog-troubled cities from the “moderate” to “serious” category, and in many observers’ estimation, it looks like the area is headed toward missing another federal clean-air mark in 2013. Last summer, aided by record-breaking heat, the area registered its worst smog readings ever, officially overtaking Houston in the bad-air rankings.

A few weeks ago, however, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality issued a report predicting that, based on “photochemical modeling,” the nine-county area around Fort Worth and Dallas will have its cleanest year for smog since monitoring began a decade ago.

A few weeks ago, however, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality issued a report predicting that, based on “photochemical modeling,” the nine-county area around Fort Worth and Dallas will have its cleanest year for smog since monitoring began a decade ago.

The prediction drew howls of disbelief in some quarters. TCEQ staffers acknowledged, in their report to commissioners, that the EPA as well as many of those who attended public hearings on the plan expressed doubts that the plan could actually produce the required reductions in air pollution by a 2013 deadline.

“That sounds like quite a challenge, especially with the drought continuing, until you factor in that hell will be freezing over as well,” said Jim Schermbeck, director of Downwinders at Risk, which has fought for years — with some notable successes — to improve North Texas air quality. “Our own computer modeling shows that by next summer, pigs will be flying and Kim Kardashian will be married for life.”

But one other veteran of the Texas air pollution wars thinks he may know part of the basis for TCEQ’s rosy predictions.

Neil Carman, clean-air program director for the Sierra Club of Texas, said he thinks the agency predictions could come true if new initiatives by the EPA force Texas’ coal-fired power plants to cut back on their pollution — the very federal controls that the state has been opposing. “The results could be significant,” he said.

In fact, he suggested that major changes in Texas air quality and air pollution regulation may actually be on the horizon. Not because state regulators have gotten tougher or that longtime polluters have seen the light, but because of a combination of federal initiatives, lawsuits against polluters by his group and others, and market forces that could substantially reduce pollution from power plants.

Whether North Texas air has a sparkling year in 2012 or not, it’s clear that factors are converging that could have long-lasting effects on the air we breathe. The result may be cleaner air — or air that’s just dirty in different ways.

Pollution from the cluster of cement plants around Midlothian has decreased in recent years in part because dirtier plants have been phased out — under pressure from the Downwinders — and most of those remaining are burning cleaner than in the past. New federal rules regarding cross-state air pollution are expected to significantly affect emissions from power plants. The EPA has also taken over some air-quality permitting process from the state, to more strictly enforce clean-air rules, and begun to enforce rules on greenhouse gas emissions. And new regulations on mercury emissions — where Texas’ emissions far outstrip those of any other state — are also due to go into effect soon.

Groups including the Sierra Club are suing Luminant, North Texas’ largest electricity generator, for thousands of violations of emissions rules over a several- year period. Luminant has threatened to shut some of its coal-burning units and lay off workers as a response to the tighter federal controls. What’s more, the future of Luminant and all of its coal-fired plants have been called into question repeatedly this year by financial and energy industry analysts. Some analysts say that investors who bought the huge utility in 2007 added so much to the company’s debt load that Luminant doesn’t have the money to make the expensive retrofits that the company has known for years it needed to clean up its emissions.

On the other side of the equation, pollution from the gas drilling industry will increase with every new well, compressor station, or pipeline that goes into operation. A much-criticized study commissioned by Fort Worth and released earlier this year found that only a few of the gas facilities researchers tested were, individually, emitting dangerous quantities of toxins. However, the study found that almost all the sites were producing some toxic emissions — and researchers didn’t even include fracking or drilling activities in their conclusions. Nor did they attempt to assess the health or air-quality effects of the combined load of pollutants being produced by the thousands of wells and other facilities in North Texas. Not surprisingly, Schermbeck and others say that gas drilling pollution is dragging down the region’s attempts to meet air-quality standards, even while improvements are being made in other industries.

Drilling industry critics have raged in recent months over the decision by the Fort Worth City Council to do nothing to reduce the environmental dangers posed by gas-related activities. But there, too, some new efforts by the EPA could soon begin to make a difference.

Overall, Carman said, Texas has been seen as “the Wild West” for polluting industries in the past.

“But what they’ve gotten away with for decades is about to come to an end,” he said.

What happens at the huge coal-fired power plants that Luminant Energy operates in northeast Texas doesn’t stay in northeast Texas. The energy produced there powers homes and businesses across the Metroplex, and a lot of the soot and chemicals emanating from the Big Brown, Monticello, and Martin Lake plants end up here as well. The three plants are reckoned to be some of the heaviest polluters in the state, responsible for more than a quarter of Texas’ industrial pollution.

In a 2008 story initially researched for the Center for Public Integrity and co-published by Fort Worth Weekly, reporter Joaquin Sapien and data analyst Ben Welsh explained how monitors on the Luminant plants automatically record each time one of those facilities emits more pollution than its permit allows. Despite thousands of such “exceedances” reported, TCEQ had never taken action to force Luminant to fix the problem or to punish the company for its ongoing illegal emissions.

In October, the Sierra Club, Earthjustice, and the Environmental Integrity Project filed notice that they intend to sue Luminant for continuing those practices up to the present — now allegedly amounting to more than 38,000 separate violations over the years.

“I was shocked at how pitiful the regulation is,” said Carman, who worked for the state environmental agency for 12 years. “This is a big deal. This stuff drifts toward the Metroplex.”

A Luminant spokesperson said the company is reviewing the allegations made by the environmental groups, but that “Luminant stands by its strong track record of exemplary compliance in meeting or outperforming all environmental laws, rules, and regulations.”

A Luminant spokesperson said the company is reviewing the allegations made by the environmental groups, but that “Luminant stands by its strong track record of exemplary compliance in meeting or outperforming all environmental laws, rules, and regulations.”

TCEQ responded in an e-mail, saying that, “when alleged violations meet the enforcement initiative criteria, the TCEQ vigorously pursues enforcement.”

When industry analysts started talking about how Luminant — formerly TXU — and its parent company Energy Future Holding should consider retiring all those plants, it got a lot of people’s attention.

Essentially the case made by some analysts is that Luminant is so deep in debt, and its financial outlook so grim, that there’s no way the company could afford the scrubbers and other upgrades that those plants have needed for years.

The company has announced plans to idle two units at its Monticello plant, close three of its lignite mines, and lay off several hundred workers — and said those steps would be made necessary by the EPA’s institution of rules limiting pollution that blows from one state to another. Those “cross-state” rules will affect mostly power plants.

A Luminant spokeswoman said that unless the cross-state regulations are delayed, the company will idle two units at Monticello on Jan. 1. But until the rule is finalized and until a court rules on the requested stay, the company won’t “subject our employees to layoff notices” when layoff might not be needed, she wrote in an e-mail.

Tom Sanzillo, a former deputy controller for New York state, notes that the 2007 buyout of TXU by Energy Future Holding added billions of dollars in debt to the plants, whose value has since been written down by EFH to the point that the investment is now considered to be worth only about 20 percent of its value at the time of the buyout.

In a report prepared for the Sierra Club and released in March, Sanzillo said that the coal-fired plants had been financially mismanaged and are losing revenues “due to low natural gas prices and new wind energy” sources, two trends that are likely to continue.

In a report prepared for the Sierra Club and released in March, Sanzillo said that the coal-fired plants had been financially mismanaged and are losing revenues “due to low natural gas prices and new wind energy” sources, two trends that are likely to continue.

Asked to comment on the deep-in-debt depictions, Luminant’s response was that the company “will comply with all federal regulations, and of course the health and safety of the communities we serve is paramount.”

“Luminant would tell you the cause of its problems is EPA regulations,” Sanzillo wrote in an opinion piece for the Houston Chronicle. But in truth, he said, “its problems have exactly nothing to do with common-sense clean-air protections” and everything to do with poor financial choices and increased competition from other sources of energy. Earlier this year, he said, Luminant was paying 77 cents of every dollar it brought in, to cover interest on its debt — compared to less than 7 cents per dollar for most utilities in this country.

“One national industry consulting firm has called for the retirement” of all such coal-fired plants in Texas, Sanzillo wrote.

Now is the time, he said, for decision-makers in Texas and elsewhere to figure out how to “ensure a smooth transition to a more financially stable and reliable supply of electricity.”

Carl Edlund, in charge of air quality and other programs for Region 6 of the EPA, said the agency is “not about passing regulations to shut down power plants.”

“There is a lively dialogue” going on among the EPA and several state agencies about continuing the reliability of the state’s power supply, Edlund said, “especially after last summer,” when record-setting heat and drought pushed power usage to the danger point. “There need to be ways to ensure [electricity supply] reliability, and I think we can do it.”

Ask Edlund to review all the fronts on which the EPA is working to improve air quality in Texas, and he pauses to take a very deep breath.

It’s a long list. Some of it has to do with regulations that EPA is involved in all over the country. But other items are on the list because the federal agency decided that TCEQ wasn’t getting the job done. On some fronts, the state has taken the EPA to court.

Take the cross-state rule. TCEQ chairman Bryan Shaw has said that those regulations, aimed mostly at smog-related pollution, are “not based on facts” and will have “significant adverse impacts to this state” — including to the state’s electric power grid.

Edlund said the rule, to be released in final form within a week, is an attempt to reduce the impact that states have on one another. It sets a statewide annual cap on emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides and affects 28 states in the eastern half of the country.

Critics of the rule, including TCEQ, have said that the rule will require many utilities to add pollution-control hardware in a timeframe that’s impossible to meet, thus forcing companies to shut down some coal-fired plants to stay within legal limits on emissions.

Edlund said that because the regulation allows utilities to “trade” allowances with one another, the early deadlines shouldn’t be an insurmountable problem. Later on, as the amounts of permitted pollution decrease, he said, companies may indeed have to add scrubbers and other pollution-control devices.

He half-jokingly referred to the cross-state rules, which take effect next year, as one of EPA’s “early Christmas presents.” Another new rule, to be finalized next spring, will limit the amount of volatile organic compounds that can legally be emitted by “new sources” — including new and refracked shale gas wells. And coming sooner than that is a new regulation on mercury emissions, the first time that the EPA has regulated emissions of that dangerous chemical from power plants. There are several technical ways for power plants to cut their mercury pollution, Edlund said.

He half-jokingly referred to the cross-state rules, which take effect next year, as one of EPA’s “early Christmas presents.” Another new rule, to be finalized next spring, will limit the amount of volatile organic compounds that can legally be emitted by “new sources” — including new and refracked shale gas wells. And coming sooner than that is a new regulation on mercury emissions, the first time that the EPA has regulated emissions of that dangerous chemical from power plants. There are several technical ways for power plants to cut their mercury pollution, Edlund said.

“Tremendous health benefits will accrue from that standard,” he said, since mercury is a nerve toxin.

Texas is also fighting the EPA over the agency’s institution of limits on greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to global warming. As with mercury, Texas is the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases of all the states. They include carbon dioxide and methane. The rules require companies that want to add substantial amounts of emissions — power plants, again, plus refineries, chemical plants, and other heavy industry sites — to apply for a permit before the new or expanded facility is built.

“Texas was the only state that said heck no [to greenhouse gas rules], so we’re doing that [issuing permits],” Edlund said.

The EPA has also fought TCEQ on its enforcement of existing air pollution regulations, especially state rules on “flexible” permitting that both the EPA and environmental groups say allowed major industries to get away with far more pollution than is allowed and with few ways for the public to scrutinize or object to what was happening.

“No other state allows this,” Gina McCarthy, an assistant EPA administrator, told a U.S. House subcommittee at a hearing last spring. Texans, she said, were not getting the same level of public health protection that residents of other states enjoyed.

The federal agency disapproved parts of the state’s permitting program and took it over.

Edlund said that the EPA is now working with industries to replace their current emission permits with ones that meet federal clean air rules. The process, he said, “will take a couple of years, and there will be public scrutiny.”

Edlund and McCarthy, as well as Texas environmental leaders, say that cleaner air will produce huge benefits for Texans — and not only in healthier air for people to breathe.

“We could have people in factories building solar panels, green jobs, clean jobs,” Carman said. “Have you been out around Abilene? There are thousands of wind turbines — wind energy is helping keep electric rates down.”

“We could have people in factories building solar panels, green jobs, clean jobs,” Carman said. “Have you been out around Abilene? There are thousands of wind turbines — wind energy is helping keep electric rates down.”

Edlund repeated a point that local gas drilling critics have been making for years: The same measures that will decrease the cancer-causing emissions from gas wells, compressor stations, and other facilities will also save the gas companies money, because they will cut down substantially on the loss of natural gas to the atmosphere. Tighter controls on VOC emissions from gas wells, he said, “certainly are not going to have a huge negative impact” on the industry.

TCEQ spokeswoman Andrea Morrow said that agency has spent a lot of time and resources “improving our understanding of emissions associated with oil and gas production” in North Texas. She said that TCEQ has implemented rules reducing compressor engines’ nitrogen oxide emissions, a major factor in ozone problems.

Edlund said TCEQ has completed a new total “inventory” of pollution emissions from the oil and gas industry. With that, he said, “we’ll be able to see how much impact there is from the Barnett Shale” on North Texas air pollution.

The battles continue, of course. Schermbeck and the EPA are both keeping an eye on a permit granted to one of the cement kilns at Midlothian to burn what’s called “shredder fluff” — materials used in car interiors. The permit was granted without public notice because the kiln operator, TXI, claimed there would be no increase in the kiln’s overall emissions. Edlund said that because parts of the “fluff” may contain PCBs, the EPA has jurisdiction over the permit and will follow up with TCEQ on the matter.

TCEQ commissioners were to vote Wednesday morning on whether to approve the DFW area clean-air implementation plan that includes the projection of extraordinarily clean air next year. The plan is supposed to allow the area to meet the current federal clean-air act standard of 85 parts per billion of ozone, by the target date of 2013.

“It doesn’t appear that that’s going to happen,” Edlund said, but that’s not really what the EPA is worried about, he said. The agency is moving on, to put in motion the steps that need to be taken for the Metroplex to meet a new, more stringent standard of 75 ppb over the next three years (but less stringent than a significantly lower threshold that President Barack Obama set aside recently).

Within a week, Edlund said, EPA will propose the boundaries of the area in North Texas that will be included in the new plan and begin putting together proposals for rules and regulations that will help the area meet that more ambitious goal.

“What’s important is that Texas can’t sit on its heels. It has to develop a new plan” to meet that standard, he said.

Asked where Texas ranks nationally on air pollution problems, Edlund didn’t have an answer. “It’s not like American Idol,” he said.

Morrow said that the DFW non-attainment area has come close to meeting the current clean-air standards and that ozone levels here dropped by 15 percent over the last decade, even as the population grew by 20 percent. The DFW area was doing well compared to other big cities until this summer, she said, but it still ranks well below several other large metropolitan areas for ozone.

Inside the state, Edlund said, Houston was doing better than North Texas on some counts, but ended up “back in the soup” during the long hot summer just past. The Metroplex, he said, “has become the most stubborn to deal with” among the state’s problem areas.

He said the EPA’s reforms of the state’s permitting process should bring a lot of clarity — no pun intended — to air quality problems.

Is the Wild West era ending in Texas?

“I would hope so,” he said.