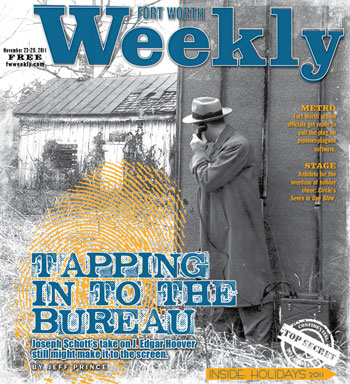

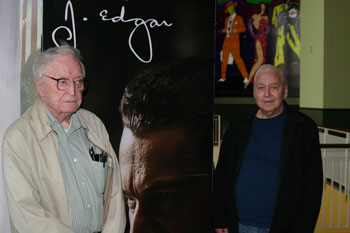

The theater wasn’t crowded when Clint Eastwood’s latest biopic J. Edgar played recently at Movie Tavern. Mid-morning on a weekday isn’t exactly prime time for a theater or a tavern, but it’s a fine time for Joseph L. Schott. At 90, he feels best early in the day. He pretty much had the theater to himself, which was good considering his running commentary.

“That’s 9th and Pennsylvania,” he said over the movie’s opening shot of the U.S. Department of Justice building. J. Edgar Hoover headed up the Federal Bureau of Investigation there from 1935 until his death in 1972.

Toward the movie’s end, a scene depicts a well-padded Leonardo DiCaprio as Hoover donning his mother’s dress and jewelry in front of a mirror.

Toward the movie’s end, a scene depicts a well-padded Leonardo DiCaprio as Hoover donning his mother’s dress and jewelry in front of a mirror.

“That’s bullshit,” Schott said loudly enough to be heard over the deafening audio assault so common in theaters these days.

A young couple sitting a row ahead glanced at each other and stifled giggles.

Schott knows a thing or two about the man who was once considered the country’s top crime-fighter. Schott spent 23 years as an FBI agent assigned to a Fort Worth field office and once escorted Hoover and FBI Associate Director Clyde Tolson on a trip from Dallas to Austin in 1959. After he retired, Schott wrote No Left Turns: The FBI in Peace & War, a hilarious account of his time as a G-man serving under the obsessive, dictatorial Hoover.

The book was published in 1975 and quickly went into its second and third printings, prompting Playboy to purchase an option to turn the book into a movie. Nothing came of it. The book would be optioned several times over the years, but no film was ever made.

“People would call me and say they’re interested, always independent producers,” Schott said. “They’d try to put together directors and writers and go to the bank and get money.”

Banks were leery, or something else would fall through. Either way, the option would run out and revert to Schott. Then somebody new would come along with big plans.

The latest is Fort Worth filmmaker Tom Huckabee, who partnered with writer David Poynter to put together a screenplay that’s every bit as uproarious as the book. Hollywood’s copycat mentality means the release of J. Edgar might grease the wheels to bring No Left Turns to the screen. A Los Angeles producer is interested in turning the book into a TV series described as a cross between Mad Men and The Office.

More than 35 years after its release, the book may be closer than ever to being produced.

“I hope [Schott] gets to see something before he dies,” Huckabee said.

Schott lives in the Tanglewood neighborhood near Colonial Country Club. With the help of a part-time assistant, he cares for his mentally retarded son, Rolf, 63, and watches old movies, reads, and tries to enjoy his remaining years.

Schott lives in the Tanglewood neighborhood near Colonial Country Club. With the help of a part-time assistant, he cares for his mentally retarded son, Rolf, 63, and watches old movies, reads, and tries to enjoy his remaining years.

“I’m 90; I don’t have a grand future,” Schott said.

Rolf sat nearby singing “The Eyes of Texas” to himself while Schott discussed his book and life on a recent morning. Schott’s wife, Eleanor Wilson Schott, was a longtime news reporter and entertainment columnist at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. She died in 2007.

Rolf was a toddler when Schott began dating Eleanor. He adopted Rolf — “along with his mother,” he likes to joke — when they married in 1951.

“Whatever money I got [from a movie or TV project], I would put in the trust for him,” he said.

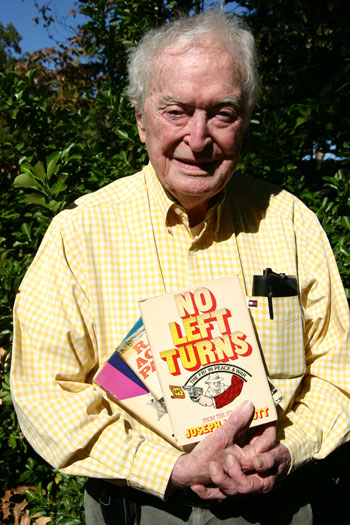

Joe Schott is tall and rangy, although nine decades have conspired to rob his legs of their sturdiness. Slightly stooped, he still carries himself with understated confidence and authority sprinkled with self-effacing humor. The combination makes him instantly likable.

“You see before you what is left of one of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI agents,” Schott said, sticking out his hand in greeting as he shuffled into his living room to meet a reporter. He was wearing a checkered shirt with eyeglasses and pens stuck in the pocket, corduroy pants, and two pairs of socks — one brown, one black — for extra warmth.

Schott grew up in Cleburne in the 1930s and still exudes small-town humility despite having earned a master’s degree, teaching on the college level, and authoring several books.

We sat on what he referred to as “my wife’s couches.” He loved his wife but isn’t crazy about her favorite sofas — they sit so low to the ground that a lanky old codger can hardly get up from one without a helping hand. Schott has lived in the house since it was built in the 1950s. Like its owner, it’s a bit ragged these days, but doing well, all things considered.

The room’s shelves are stacked deep with books on a wide range of topics. Curiosity might have killed the cat, but it inspires Schott. His published works include nonfiction books on building the Panama Railroad (Rails Across Panama), the Philippine Insurrection during the Spanish-American War (The Ordeal of Samar), and the Congressional Medal of Honor (Above and Beyond).

No Left Turns describes how he “sort of wandered into the bureau in 1948, hung around for 23 years, and then wandered out again.”

He wasn’t gung ho about the FBI, or any job for that matter. But he was willing to hunker down in a career and do a decent job as long as it offered interesting moments from time to time. He was an Army reservist stationed at Fort Hood in 1948, earning barely enough money to survive while he worked on his master’s thesis. Higher education offered no guarantees. A master’s degree in English was “a fragile shield to ward off the assaults of a predatory economy, especially in Texas,” he wrote in the book.

He wasn’t gung ho about the FBI, or any job for that matter. But he was willing to hunker down in a career and do a decent job as long as it offered interesting moments from time to time. He was an Army reservist stationed at Fort Hood in 1948, earning barely enough money to survive while he worked on his master’s thesis. Higher education offered no guarantees. A master’s degree in English was “a fragile shield to ward off the assaults of a predatory economy, especially in Texas,” he wrote in the book.

Or, as a major oil company recruiter once told him during a job interview, “The ahhl bidness don’t give a shit about Beowulf.”

The Street With No Name caught Schott’s attention at an Army base theater one day. The 1948 recruitment movie disguised as a potboiler lauded the crime-fighting techniques of the FBI. It may have been no great shakes as art, but it inspired Schott to apply for a job.

He squeezed into the FBI ranks as a file clerk but quickly soured on a dull job that netted him $35 a week. Through an old Army buddy, Schott wrangled a better job offer at the Department of Defense. That was when he learned about the FBI’s firm grip. Back then, employees resigned, retired, or got fired, but they seldom transferred to another government agency. Hoover wouldn’t have it, Schott said.

Transferring was tantamount to being a traitor, and Hoover didn’t tolerate traitors — or blacks, women, or homosexuals for that matter. Hoover demanded blind devotion, physical fitness, and moral certitude from his white male agents. So when Schott announced in 1949 that he was abandoning clerical life for loftier peaks in another government agency, he found himself facing an angry supervisor who characterized him as “disloyal.”

“What kind of disloyalty are you talking about?” asked Schott, who’d earned a Bronze Star and Purple Heart as a soldier during the Normandy invasion in World War II.

“Disloyalty to the director,” the supervisor said.

Hoover was among the most powerful men in the country. He didn’t want his employees switching agencies, and his influence meant job offers could mysteriously disappear. The ultimatum/opportunity: Leave the FBI and never work at another government agency, or stay and take the test to become an agent. No guarantees. Fail the test, and it was back to clerical duties. Pass the test, say hello to a new career.

Hoover was among the most powerful men in the country. He didn’t want his employees switching agencies, and his influence meant job offers could mysteriously disappear. The ultimatum/opportunity: Leave the FBI and never work at another government agency, or stay and take the test to become an agent. No guarantees. Fail the test, and it was back to clerical duties. Pass the test, say hello to a new career.

The FBI soon welcomed its newest agent.

Hoover’s FBI was fraught with so many rules that it was impossible to follow them all. The director could demote, transfer, or fire anybody at any time, Schott said.

He saw agents as falling into two camps: impassioned, gung ho G-men with a blind obedience to Hoover, willing to snitch out any co-worker who dared utter a disparaging remark about the director or the bureau; and the nervous working stiffs trying to do their work and hold onto their jobs without screwing up or drawing unwanted attention. Divorce, drunkenness, or any number of social miscues could mean instant termination or reassignment to some FBI version of Siberia.

Schott was part of a smaller third camp. Neither impassioned nor panicky, he glided through his career like Groucho Marx, cracking sly jokes and refusing to drink the Kool-Aid, yet maintaining a low enough profile to avoid termination or reassignment. Part of Hoover’s power came from holding secretive and potentially damaging information on almost everyone he knew. Schott wasn’t above using this technique when a supervisor or inspector tried to bust his chops for some imagined failing.

Schott did his job and kept his eyes and ears open. Posted to Fort Worth, he was among a dozen agents with jurisdiction over federal crimes such as kidnapping, bank robbery, extortion, and interstate transportation of stolen property. “I liked it very much,” he said. “I just got tired of it.”

Other odd assignments would come through, such as the time Schott was told to investigate a woman who had applied for a job at Bell Helicopter. He talked to her previous supervisor, who described her as a nymphomaniac. Schott included the descriptive word in his report, but was told by his supervisor to tone down the language. Nymphomaniac became “woman of easy virtue,” Schott recalled with a laugh.

Retired FBI agent James White worked alongside Schott back then and described him as standing out among all the white-shirted, subdued-tie-wearing, often humorless agents.

“Joe was one of the smartest agents in the bureau,” White said. “He has a command of the language. He was very amiable and easy to work with. His memory is still fantastic.”

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 in Dallas meant a whole new series of assignments that, despite the historic nature of the event, were still mostly mundane.

“We had to talk to every damned drunk who’d call up at 2 or 3 in the morning saying they had information about it,” Schott said. “When you got a call, you had to get out there within 30 minutes.”

A frequent caller was assassin Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother, Marguerite, who lived in Fort Worth, liked to talk, had an inflated sense of her own importance, and could be an emotional yo-yo during conversations. She once complained that she didn’t receive a portion of the money donated to the widow of Dallas policeman J.D. Tippit, who was shot and killed by Oswald.

“She’d say, ‘I am the mother of history, and I need to be treated with more respect.’ We had to sit there and take that stuff,” Schott said.

“She’d say, ‘I am the mother of history, and I need to be treated with more respect.’ We had to sit there and take that stuff,” Schott said.

Schott retired from the bureau in December 1971 and went on to teach criminal justice on the college level. He was associate professor and director of the Texas Christian University criminal justice program from 1976 to 1986, a job that he enjoyed for the most part, as much as he could enjoy any job.

But he always knew he would write a book about the FBI.

Five months after Schott retired, Hoover died. And four years after that, Schott’s book was published. Most books about the powerful FBI director were either vitriolic or sanctimonious. Once again Schott chose a different approach. He viewed Hoover as talented in some respects but flawed and mercurial.

“It’s a lot like this Joe Paterno problem,” he said, referring to the longtime Penn State football coach who was fired recently amid controversy over alleged sexual misconduct by a member of his staff. “You let a guy build up this mystique like Hoover, then when he gets old, you can’t get rid of him.”

Schott neither loathed nor loved the director and his bureau. Instead, the retired agent planted tongue in cheek and wrote about “institutional insanity, created at the top, catered to in the middle, causing grown men, officers of the federal government, to act like characters in a vaudeville skit.”

And never was vaudevillian behavior more apparent than when Hoover came to Dallas and required a motor escort from Love Field to Austin. It would become one of the funniest chapters in Schott’s book and the focus of Huckabee and Poynter’s screenplay that is being considered for a TV show.

Schott had no idea the book would upset some agents so much that they’d turn on him. Newspapers across the country reported on Schott being kicked out of a fraternal group of former FBI agents after No Left Turns appeared. The 14-member executive board of the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI expelled Schott on grounds that his book “maligned the integrity and backgrounds of agents” and “downgraded the prestige and image of agents.”

Schott had no idea the book would upset some agents so much that they’d turn on him. Newspapers across the country reported on Schott being kicked out of a fraternal group of former FBI agents after No Left Turns appeared. The 14-member executive board of the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI expelled Schott on grounds that his book “maligned the integrity and backgrounds of agents” and “downgraded the prestige and image of agents.”

Schott was irritated, mostly because his wife enjoyed attending the group’s annual party. But the snub created headlines, so Schott exploited them for book sales. “I got on the front page of The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times,” he said.

His 10 years of FBI experience probably wasn’t the reason Schott was chosen for the plum assignment of accompanying Hoover and Tolson to Austin in 1959. The short, stocky Hoover demanded his agents adhere to strict weight guidelines, and he preferred nonsmokers in an era when more than half of the adult population smoked. Schott was 6 feet tall, weighed 175 pounds, and he didn’t smoke. A supervisor pegged him for the job.

“I sincerely believe, without reservation, that this visit is perhaps one of the most momentous events, not only of our bureau careers, but of our entire lives,” Schott recalled the supervisor saying with a solemnity normally saved for church or funeral services.

That kind of rhetoric often prompted Schott to spout off with a wisecrack, but he wisely kept his pie hole shut this time. Hoover was big news, and even Schott was excited.

A small army of agents spent days planning details of the trip. The supervisor drove the car with Hoover and Tolson. Hoover insisted on riding in the back seat, on the right side. He’d once been injured in a car wreck while sitting in the left rear seat, and he refused to sit there again. Also, the accident occurred during a left turn, and Hoover no longer allowed his drivers to make left turns. This complicated the route to Austin in those days before interstate highways.

Schott followed in a second car as a sort of emergency backup. He was relieved that he didn’t have to ride with Hoover and Tolson. After all, Schott’s tendency to share inane trivia and irreverent remarks often went unappreciated in bureau circles, and Tolson was a “super hatchet man … in an agency swarming with hatchet men,” Schott said.

Fort Worth was home to Schott, and he didn’t want to move. Making a poor impression on Hoover or Tolson might mean he’d get transferred to some unwanted job or city. On the other hand, making too good of an impression could be just as dangerous — he might get transferred to Washington to work more closely with Hoover, which meant total devotion to one’s job and a higher level of scrutiny.

So Schott kept his distance but made sure to closely observe the top cop and his hatchet man during the two-day trip. Their expectations were outrageous. Hoover and Tolson required separate hotel rooms with precise expectations regarding the softness or firmness of mattresses, the size of ice cubes (Hoover liked big ice cubes), and the color of their robes (Hoover preferred brown and white — and he wanted his robe folded with the brown side up).

There have long been rumors about a closeted love affair between Hoover and Tolson. But Schott doesn’t believe the outwardly homophobic Hoover would have acted on any desires he might have had, certainly not with Tolson as depicted in the new movie.

He also pooh-poohs innuendo about Hoover being a secret cross-dresser. Hoover would have been repressed with a capital R, Schott said, because of the director’s all-consuming desire to be viewed as the most powerful, courageous, and dependable policeman in the country and his fear of giving anyone material with which to blackmail him.

“I had the opportunity to watch them for a couple of days,” Schott said. “He was a very private man. Those intimate movie scenes had to be dramatic touches.”

Hoover was going to Austin as a political favor for U.S. Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson, who had asked the director to speak at an important luncheon. Afterward, Hoover and Tolson planned to return to Dallas and fly back to Washington.

The bombastic Johnson, however, wanted to show Hoover a big time and dragged him on several unplanned excursions, including a trip to his ranch. The glad-handing, extravagant Johnson hauling the neurotic, self-obsessed, and reluctant Hoover all over Central Texas provided endless comic relief, and it’s what attracted Los Angeles-based producer Jennifer Orme Erwin to the project.

“While working with former FBI agent John Douglas on Mindhunter, I became very interested in J. Edgar Hoover and the history of the FBI and started researching,” Erwin said. “No Left Turns stood out among all the books I read on Hoover. Joe Schott’s take on the bureau is not only insightful but downright hilarious.”

She is working with a production company to develop the book into a series and is currently looking for a writer.

“Since the story spans an extensive amount of time, we think the material would be best served as a television series,” she said.

Schott has heard it all before. Maybe this time will be different. The old author is on the tail end of life. He would enjoy seeing his book appear on the big or little screen. But he’s OK if yet another possible production turns into one more bunch of nothing.

“I’ve got a pretty good income,” he said. “I’m not going to starve.”