Everyone was talking at once, and everyone was passionate — mostly about the same thing. But they weren’t getting anywhere on basic questions like where people would camp. Finally, a waifish 23-year-old stood up and admonished the group for not establishing any sense of order. They mocked her and shouted at her, but in the end they handed her that most powerful badge of office — a clipboard. And so Mackenzie Wainwright of Fort Worth helped get Occupy Dallas off the ground.

From high school students to retirees, approximately 50 people were scattered around the grass at the John F. Kennedy memorial in downtown Dallas on Oct. 3, and they were equally excited and angry. They refer to themselves as the 99 percent — meaning everyone except the wealthiest 1 percent of the population in this country who control 42 percent of the wealth. They’d all shown up to plan a mass occupation of downtown Dallas, following in the footsteps of Occupy Wall Street, an ongoing leaderless, largely structureless occupation of New York’s financial district by thousands of those who feel disenfranchised in this country these days.

From high school students to retirees, approximately 50 people were scattered around the grass at the John F. Kennedy memorial in downtown Dallas on Oct. 3, and they were equally excited and angry. They refer to themselves as the 99 percent — meaning everyone except the wealthiest 1 percent of the population in this country who control 42 percent of the wealth. They’d all shown up to plan a mass occupation of downtown Dallas, following in the footsteps of Occupy Wall Street, an ongoing leaderless, largely structureless occupation of New York’s financial district by thousands of those who feel disenfranchised in this country these days.

The protests against corporate greed, joblessness, and the actions of financial institutions have spread to cities all over the world — including Dallas and, on a smaller scale, Fort Worth. Thus far almost 1,000 protests have taken place in 82 countries.

The Wall Street protest itself has been compared to the “Arab Spring” protests — they share the same kind of civil disobedience and resistance coupled with promotion through social media.

Protesters camp out in an area, establish general assemblies that vote on every action taken, and organize groups to provide media, food, sanitation, and even libraries and day care. They may not have a detailed political platform worked out, but if polls are to be believed, they have support and sympathy of a majority of the people in this country — including even some leaders of the institutions they’re protesting.

“I can understand their frustration,” the president of the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank told Fort Worth business leaders last week.

The youngest 99 Percenters have grown up under the cloud of financial ruin that neither they nor the country can find their way out of. Where previous generations had a somewhat clear path to follow — college, marriage, job, retirement — these kids have found that path blocked. For them, the American dream and its promise of opportunity seem to have expired.

The older generations just want things to be as good as they remember when they were younger. They’ve seen their retirement accounts evaporate and their children (or grandchildren) move back home. And all three generations are outraged that the richest one percent is doing better than ever, in large part because they have used their financial and political power to stack the deck in their favor. Politics ruled by corporate money, the vastly widened gap between rich and poor, and the looting of the economy by the wealthy and powerful — one way or another, they want those things to stop.

The uprising comes as no surprise to Southern Methodist University professor Ravi Batra. In his 1978 book The Downfall of Capitalism and Communism, the economist predicted that Soviet communism would die out by the turn of the century and that monopoly capitalism would “create the worst-ever concentration of wealth in its history, so much so that a social revolution would start its demise around 2010.” People may have laughed then, but they aren’t laughing now.

The uprising comes as no surprise to Southern Methodist University professor Ravi Batra. In his 1978 book The Downfall of Capitalism and Communism, the economist predicted that Soviet communism would die out by the turn of the century and that monopoly capitalism would “create the worst-ever concentration of wealth in its history, so much so that a social revolution would start its demise around 2010.” People may have laughed then, but they aren’t laughing now.

“Neither party has any clue what’s going on,” said Batra. “On Obama’s side they’re spending more and more … it’s not helping at all right now. And on the Republican side they want to do what George Bush did, and that’s what created the problem to begin with. None of them has any clue. You have to give up everything that has been tried in the past 20 years. All of the official policies have to be given up if you want to create more jobs. And once that is done, it should be very easy.”

While Occupy protests began in Fort Worth and Dallas just days apart, there were some dramatic differences. The group that gathered in Burnett Park for Occupy Fort Worth was relatively small — maybe 100 protesters, watched over by a dozen or so bicycle cops. Speeches were made and committees formed (although at times it seemed there were as many committees as there were members). The group made a spirited march through downtown without incident.

In Dallas, more than 700 people turned out. On the first day of the protest there, doubt and fear were almost tangible. Half a dozen or more police SUVs waited just across the street. When scouts sent out by the protesters reported barricades at the Federal Reserve and a large police presence, paranoia started to take hold.

With YouTube videos of violent clashes between protesters and police in other cities on everybody’s mind, medical teams were hastily assembled in case things turned violent, and protesters wrote critical information such as phone numbers for family members and lawyers on their arms in black marker. A white, privately owned helicopter hovered noisily overhead, adding to the stress on the ground.

As the number of protesters began to swell, a police spokeswoman approached Wainwright and assured her that officers would only be blocking traffic and ensuring safety — that no interference was planned. An AFL-CIO representative spoke to the cheering crowd, assuring them that labor was with them. Wainwright addressed the crowd through a bullhorn, declaring that the protest would be peaceful and that nobody would start trouble with the police.

In Fort Worth, the march went only a few blocks, past Bank of America and back, while in Dallas the protest snaked from Pike Park to the Federal Reserve Building about a mile away. Eventually, the group moved on to Pioneer Plaza.

While some of the protesters were hostile toward the Federal Reserve Bank, carrying signs demanding “End the Fed” and “God Hates Feds,” Dallas Federal Reserve president Richard Fisher did not respond in kind.

According to Reuters News Service, Fisher told a group of Fort Worth business leaders that he was “somewhat sympathetic.”

“We have a very uneven distribution of income. We have too many people out of work for too long,” he said. “We have very frustrated people, and I can understand their frustration.”

As has been the case in Occupy actions elsewhere, the North Texas protesters represented a wide variety of subcultures and ages, mostly people who had never protested anything before. Those interviewed said they just want to make a decent living wage and to take their country back from economic interests.

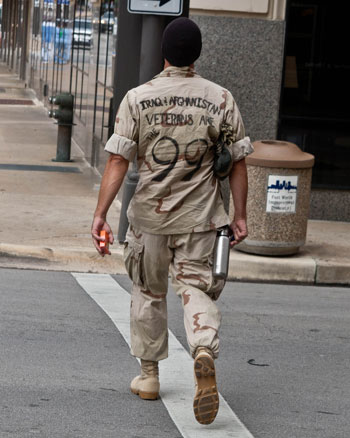

In Dallas, a man with one leg wore a sign on his back that read “I’m standing up, why aren’t you?” In Fort Worth, a Marine marched with the slogan “Iraq and Afghanistan veterans are the 99%” written in black marker across the back of his shirt.

In a recent article on the Truthout webpage, Batra detailed the events that he believes got us to this point:

• Ronald Reagan’s income tax cut of 1981 that benefited the rich but was financed by sharply raising all other federal taxes — paid mostly by the poor and the middle class.

• Unenforced antitrust laws, leading to mergers among large and profitable firms but killing off high-paying jobs in numerous industries.

• Oil industry mergers permitted in the 1990s that are now preventing oil prices from falling in the middle of the worst slump since the 1930s.

• Relentless mergers allowed among pharmaceutical and health insurance companies, so that America spends a far higher share of its gross domestic product on healthcare than other countries — and the care is still mediocre by European and Japanese standards.

• Unchecked use of outsourcing that kills high-paying jobs in manufacturing and services.

• Ignoring the growth of the trade deficit that has destroyed the manufacturing base.

• The 1999 repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act under President Bill Clinton that led to reckless lending by banks and an unprecedented housing bubble, which collapsed in 2007 to help trigger the ongoing slump.

• The Bush tax cuts and bailouts that further benefited the rich while nearly doubling the government debt.

• And finally, the decimation of the real minimum wage by Reagan and other Republicans. In 1981 the hourly minimum wage bought $8 worth of goods compared to $6 by the end of Reagan’s presidency in 1988 and a mere $5.15 in 2006 under George W. Bush.

Batra called on the Occupy Wall Street protesters to make the correction of those nine basic problems a priority.

Batra called on the Occupy Wall Street protesters to make the correction of those nine basic problems a priority.

He predicted that the protests will have a strong impact on the 2012 elections, “especially because the economy is going to be just as bad as it was in 2008 [and] it could be worse.”

The Occupy movement, he said, will draw “a lot more angry people. A lot more jobless people will be there. If unemployment benefits are not extended, then you will have really bad economic troubles next year.”

At that first Dallas meeting, with no established leader, the discussions kept getting hijacked in mid-topic and sent off in other directions. The important questions, like logistics of where people would camp, seemed to be getting pushed to the side. The 99 Percenters have had enough of being told what to do and aren’t about to give the title “leader” to anyone.

It didn’t take long to re-establish order, however. Wainwright admonished the group for not establishing any structure for the discussion, such as not having anyone taking “stacks” (a system where one person manages a list of the people who have asked to speak before the group). People in the crowd mocked her, shouted at her to get out of the way, and said that they didn’t need any kind of system, but she deflected it back.

“Laugh it up,” she said, “but if you don’t get organized, they will take you apart on day one.”

Despite some heavy resistance and even verbal abuse, Wainwright was pressed into service, often having to act like a drill sergeant to get the group to follow procedure. Attendees grudgingly acknowledged the benefit of the stacks system, and plans for the initial meetup and march rapidly developed.

Wainwright developed the thick skin needed for this kind of job as a teenager in Fort Worth. She was active in the youth group at a Unitarian church.

“I used to plan weekend-long rallies for 300-plus youth,” she said, “They included social action, worship, and activities of all sorts. If anyone can disagree it’s Unitarians, spending hours upon hours deciding what shade of green a fucking t-shirt should be. It’s ridiculous. How do you start an argument from happening? You just stop it. You don’t sit there and placate both sides. Some decisions just have to be made.”

In a recent New York Times article, Harvard economics professor Lawrence Katz described the last 10 years as “truly a lost decade. We think of America as a place where every generation is doing better, but we’re looking at a period when the median family is in worse shape than it was in the late 1990s.”

If you’re looking for a poster child for that lost decade, it’s Wainwright. When her mother was laid off from Sprint in 2003, their family became homeless. She moved in with a friend from her high school and graduated early. She even made it into college, where she majored in sociology with a plan to open a nonprofit center for gay and lesbian teens. But when a close friend committed suicide, she found herself too emotionally devastated to continue — and ended up homeless again.

She slept on park benches, even lived in a coffee shop for a while. She now lives in Dallas and works two jobs, seven days a week, to keep a roof over her head and try to pay down her $2,100 college debt. This is a resonating theme with the younger members of the 99 Percent: Many went to college only to find there were no jobs when they graduated, but their college loan payments still came due. Like many of them, Wainwright has never known a time when financial security seemed attainable.

“I’m not asking for anything other than a job that will help me take care of my debt,” she said. “I’m not in any way asking to be on welfare. I’m not asking for people to feed me, I can feed myself. I just need to be able to earn the money to do it. I live OK now, it’s not terrible, but I still have debt, and I can’t fix my car, and I can’t do the things that I want to do because I don’t have any money, and I have to work every day. Do I wish I could work for a living wage and not a minimum wage? Absolutely. ”

The future doesn’t look so bright for people like Wainwright. In an article on tomdispatch.com, Andy Kroll pointed out that slightly more than 15 percent of all Americans “are now living in officially defined poverty, the most since 1993.”

Where previously the poverty rate had been decreasing, the last decade saw the loss of so many jobs that, to regain that ground by mid-2016, the country would need to create 280,000 jobs a month, Kroll wrote. And that’s not happening.

Wainwright, also like many of the protesters, doesn’t have a concrete idea of how to fix the problems she lives with. Largely apolitical, she only knows that someone needs to step up and that she can contribute her time, skills, and abilities to support those with ideas on how to fix the problem. She stepped in to help organize the Dallas protesters because that was what she could bring to the table.

That is typical throughout the Occupy phenomenon, which is perhaps better viewed as an idea than a movement. Ask any two 99 Percenters what they hope to achieve and how best to go about it, and you will likely receive two very different answers.

This “accept everyone’s viewpoint” philosophy is both the strength of the various Occupy gatherings and a possible Achilles heel. Concentrating solely on the grievances (corporate greed, income inequality, and the subversion of the government by the financially powerful) makes it easy to attract crowds and build enthusiasm, because those things are easily agreed upon. The meetings at each site are more focused on finding solutions than on promoting a pre-determined agenda.

Having been debated and voted on in the seemingly endless series of general assemblies across the country, those lists of demands are now mostly drawn up. What’s not clear is how unified the groups will be when it comes time to finding a mechanism for achieving those goals.

Having been debated and voted on in the seemingly endless series of general assemblies across the country, those lists of demands are now mostly drawn up. What’s not clear is how unified the groups will be when it comes time to finding a mechanism for achieving those goals.

Some 99 Percenters advocate a complete reboot with a new system of government. Others believe in reform, or simply that the show of force will change the behavior of elected officials and corporate leaders.

A less tangible hypothesis is that through the discussions and assemblies a more unified philosophy will be adopted by everyone involved, and through that understanding, change the way people vote and conduct themselves in their daily lives.

Still others, like former Dead Kennedys front man Jello Biafra, envision the 99 Percenters forming their own political party.

Louis Davis, a 99 Percenter with the Occupy Dallas group, agreed.

“If we occupy our communities and do it well, [then] we need to get ready to occupy the ballot box,” he said. “The best-case scenario is that no matter who our next president is, [he or she will] live in an occupied White House. That’s where the true change is going to be effected — when we take it to the ballot box and get people on the ballot slips.”

In contrast to Wainwright, Davis, 33, represents the more nonconventional protesters. He can trace his hippie pedigree back to The Farm commune in Tennessee. From 1998 to 2008 he traveled around Fort Worth on foot, living completely on the barter system. He worked for various businesses around town and built up sort of a barter savings account with each one. Then, when he needed something, he simply went to someone who owed him for his labor and got what he needed.

“I’ve made some concessions, because I have a home,” Davis said. “But at the same time I’m seeking to break even. I did spend 10 years with no money — that is who I am. It was a very dirty, dirty divorce. We are on speaking terms, but we are not living together. I do understand that we need some kind of representation [such as currency] so that someone can carry their labors beyond their immediate community, and I agree with that.”

Davis said that, for him, the protests speak to citizens’ dissatisfaction with “our economic system as a whole. The processes that we’ve put in place and the motivations that stir our market are not sustainable.

”It’s time to change,” he said. “For long enough the money has controlled the legislation. What this is about to me is uniting like-minded people to where we can effect change.”

He acknowledged that a lot of people compare the Occupy protests to the Tea Party, which also embodies a feeling of disenfranchisement and a distrust of hierarchy. But whereas the Tea Partiers quickly attracted heavy corporate underwriting and the support of media organizations like Fox News, Davis said, the Occupiers are going to have to depend on numbers and not big-dollar support.

He acknowledged that a lot of people compare the Occupy protests to the Tea Party, which also embodies a feeling of disenfranchisement and a distrust of hierarchy. But whereas the Tea Partiers quickly attracted heavy corporate underwriting and the support of media organizations like Fox News, Davis said, the Occupiers are going to have to depend on numbers and not big-dollar support.

“All of sudden the Tea Party came up,” said Davis, “and they grabbed themselves some seats and they are rocking votes, and I think we are stronger than them. I do believe the Tea Party is a fringe movement, and I think their timing was really good. I don’t think Big Money is going to get with us, but I think Big America is.”

Some 99 Percenters say that the Tea Party is welcome to be a part of the movement and have their voices heard, though they are at odds with most of the Occupy protesters. But while the Tea Party wants less government power, the Occupy protesters want less corporate power, ideals that are often contradictory. The 99 Percenters also seem even more suspicious of politicians than the Tea Partiers, who have aligned themselves with key political figures. Attempts to categorize the Occupy events as pro-Obama or even pro-Democrat miss the mark, as most of the 99 Percenters consider both political parties to be part of the problem.

Occupy Fort Worth took some cues on what to do and not do from the bigger protest in Dallas. When State Rep. Lon Burnam donated the rental of a portable toilet to the Burnett Park group, Fort Worth officials demanded that the protesters obtain an $80-a-day potty permit. Having seen the disagreements in Dallas over a similar permit, the Fort Worth group just sent the toilet back, with thanks.

The permit demand angered Burnam.

“These people have a right to be here, and they have a right to safe and sanitary conditions,” the legislator said. “I’m trying to help them, the demonstrators, do right, and the people responsible for the park, [Downtown] Fort Worth Inc., [which manages the park for the city], are enforcing this absurd ordinance. … The bureaucrats of [Downtown] Fort Worth Inc. and the City of Fort Worth are clueless and indifferent.”

Speaking from the park, he noted a man walking his dog nearby. “This gentleman who probably lives downtown is walking his dog in the park. And his dog can legally piss in this flower bed, but the demonstrators have no place to go, literally or figuratively.”

Was the dog exercising First Amendment rights, a reporter jokingly asked. “He’s not barking, so I’m not sure,” Burnam said.

In Dallas, the potty permit battle provoked some drama. The Occupy protesters, after a vote, agreed to take out a permit for their toilet. Other Occupy groups across the country criticized the action, claiming it opened the door for government control of the protests. The City of Dallas responded by granting the permit with a stipulation that the group obtain a $1 million insurance policy by the end of the next day or they would be forced to leave.

When no such policy was produced, the city announced that it would begin enforcing curfew laws. On a night when police were forcibly removing protesters in Boston, Dallas 99 Percenters prepared for the worst — and paranoia and lack of sleep again took hold.

Fearing a police raid, most of the group responsible for distribution of protest news moved off site. Later that day, the protest representatives announced on Facebook and their web site that police had taken up strategic positions on three sides of the park and that Department of Homeland Security vehicles had been spotted driving by. A headline on the web site read “Occupy Dallas surrounded by law enforcement.” But it wasn’t.

Fearing a police raid, most of the group responsible for distribution of protest news moved off site. Later that day, the protest representatives announced on Facebook and their web site that police had taken up strategic positions on three sides of the park and that Department of Homeland Security vehicles had been spotted driving by. A headline on the web site read “Occupy Dallas surrounded by law enforcement.” But it wasn’t.

News teams raced to cover the conflict, only to discover there was nothing happening. Two police cars stood watch over the park as always. Homeland Security has a parking garage across the street, which explained the sightings of their vehicles. When most of the news crews left, the protester media group reported that the press had been pulled out for their safety. People across the country were sending messages to the Dallas occupiers in support of a crisis that was not happening. The protester media representatives still in the park tried to set the record straight on Facebook but found that their posts were getting deleted as soon as they put them up. They gave up in disgust and went back to enjoying the campsite.

Pioneer Park that night, in reality, was nothing like the war zone portrayed on the web site. There were kids tossing sticks around, people quietly sitting around discussing politics, and a food table where you could make yourself a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and grab a bottle of water. Veteran news reporters and young hippie protesters even discussed how the world financial situation was affecting journalists. It could have been a campground anywhere in America if not for the tall buildings that loomed on the perimeter.

Eventually the portable toilet conflict was settled out of court. Lawyers for Occupy Dallas requested an injunction in federal court, but an agreement was reached before the hearing that the protesters would move to a new site just behind city hall.

In Fort Worth, tension continued to build. City ordinances forbid camping in the park, and protesters felt they lacked the force of numbers to defy the law, so they camped out on the sidewalk. During the day, marches were held. When Bank of America security guards tried to deny the group access to the sidewalk, police officers defended the protesters’ right to be there.

On Oct. 15, tents were set up along Lamar Street in such a way so as not to block the sidewalk, but the police ordered them taken down. The 99 Percenters refused, the tents wore torn down and confiscated, and five protesters were arrested to chants of “shame” and “the whole world is watching” from the other 99 Percenters. (Live audio feeds were going out during the arrests, so part of the world was at least listening.)

Musicians stood on the sidewalk singing protest songs while attorneys circulated gathering witness statements. As a lone police car drove by, the protesters yelled, “We love you guys” to the officer inside, who thanked the protesters for the sentiment.

The removal of the tents put Fort Worth on the protest map, and messages of support came in from across the country. Now the Fort Worth group’s numbers are growing daily. An exchange program has been set up so that protesters go back and forth between the Dallas and Fort Worth sites, boosting the numbers in Fort Worth and allowing the two groups to learn from each other.

Following the first day’s march, Wainwright flew to the West Coast to take part in Occupy Seattle. When she got back, she found Pioneer Park empty and the Occupy Dallas group hidden behind Dallas City Hall in the new space. The plans originally were for the group to sleep at the new site, then relocate to Pioneer Park during the day. Instead, the protesters were staying at the new site except for marches. Feeling that they had become too compliant with the city government, she voiced her concerns but felt like she was shouted down.

“They are like penned-up puppies back there,” she said.

With that, Wainwright broke off her association with Occupy Dallas. She plans on working with Occupy the Hood, a more neighborhood-oriented movement that’s still in its infancy.

All the Occupy groups, though based on similar ideas and mechanisms, are busy finding their own paths. Some will undoubtedly disappear, while others will evolve into something else. Together, though, they represent something new and potentially powerful on the world political scene. To write them off as unfocused (although they can be), or hippies (while some of them are), is to miss the bigger picture. They are not defined by any individual or location or group.

Ravi Batra’s record of predictions on world political, social, and economic developments is powerful, if not perfect. And he has some ideas about where the Occupy groups — and the unrest that they represent — are headed.

He believes that the Occupy movement will continue to grow as the economy worsens.

Next year “is going to be really bad in terms of the economy and in the stock market,” the economist and futurist said. “That will provide a lot more fodder for this movement, and then it will have a very strong impact on elections” — even possibly leading to another Democrat challenging Obama for the party’s nomination for president, he said.

“By 2016 social rebellion will overthrow crony capitalism,” Batra said.

“The best possible outcome,” of the movement, Dallas protester Davis said, “is that this occupation realizes that Wall Street is not the true place to effect change in the market, and we can take this occupation from Wall Street nationwide. If we truly are 99 percent, leaders are being born right now. The best-case scenario is that somewhere in this we become a voting bloc.”

Fort Worth writer and photographer Steve Watkins can be reached at steve@storyandphotosby.com.