I like to think I’m relatively well-liked by my colleagues in the news business and that I’ve been doing this long enough to know how to come prepared to any event I might be covering.

But really, who knew that a giant package of Twizzlers could make me a media hero at a massive prayer rally? It was all part of the already strange happening at Houston’s Reliant Stadium last weekend, where tears flowed, hands waved in the air, and prayer was on everyone’s lips but politics was at the forefront of so many minds.

But really, who knew that a giant package of Twizzlers could make me a media hero at a massive prayer rally? It was all part of the already strange happening at Houston’s Reliant Stadium last weekend, where tears flowed, hands waved in the air, and prayer was on everyone’s lips but politics was at the forefront of so many minds.

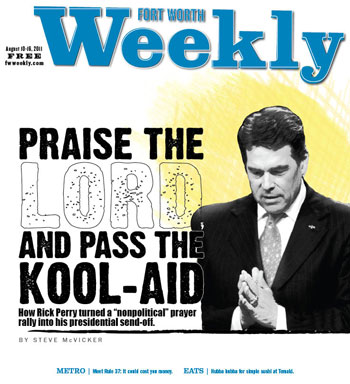

It was an event where Texas Gov. Rick Perry — who had dreamed up the event in the first place but seemed on the verge of skipping at one point — actually prayed for the president he’s been running around the country castigating for months now. And then, almost before the stadium emptied, Perry’s camp was letting slip the news that he indeed is expected to announce his candidacy for that office in the next couple of weeks. In the world of Tea Party politics, maybe using a prayer rally as a presidential campaign springboard isn’t such a Mad Hatter idea, just a cynical one.

But back to those Twizzlers … I brought them because I hadn’t had time for breakfast on Saturday morning before I’d jumped in my truck to head for the stadium on Houston’s southwest side and a designated parking area so far away that I thought we must be halfway to San Antonio.

No breakfast, no problem, I thought, remembering the scores of food and drink vendors usually on duty at the stadium, which is home to the Houston Texans football team. Big mistake: I’d forgotten that The Response, as it was called, was supposed to be a day of prayer and fasting. When I got to the area reserved for the press, I found that others of my kind had made the same miscalculation. Then I remembered the Twizzlers in my briefcase — juicy, strawberry-and-licorice-flavored strands made of Lord knows what. I pulled them out and became a very popular man. I felt like an embedded reporter sharing MREs with the troops.

In the 70,000-capacity stadium, a dark curtain at the 50-yard-line shut off half the seats. In the area in front of the curtain, the seats were filled about halfway up, and several thousand more chairs had been set up on the field. The upper decks held only a scattering of folks. And the crowd was, well, extremely white.

Organizers estimated the turnout at 30,000. I’ve been estimating crowds as part of my job for most of the last three decades, and I’m here to tell you, there were nowhere near that many people in that stadium. (Maybe the people-counters were classmates of Perry’s at Texas A&M University, where the future governor, according to transcripts published by Huffington Post last week, made mostly Cs and Ds.) My guess is, the crowd was closer to 20,000 if one is being generous, 15,000 if not. That’s still better than the low of 8,000 that organizers had talked about earlier in the week, around the time that Perry was starting to make sounds like he might not come at all.

Organizers estimated the turnout at 30,000. I’ve been estimating crowds as part of my job for most of the last three decades, and I’m here to tell you, there were nowhere near that many people in that stadium. (Maybe the people-counters were classmates of Perry’s at Texas A&M University, where the future governor, according to transcripts published by Huffington Post last week, made mostly Cs and Ds.) My guess is, the crowd was closer to 20,000 if one is being generous, 15,000 if not. That’s still better than the low of 8,000 that organizers had talked about earlier in the week, around the time that Perry was starting to make sounds like he might not come at all.

Just nine days earlier, U.S. District Judge Gray H. Hiller of Houston had dismissed a lawsuit filed by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, a national atheist group that accused Perry of crossing the constitutional line separating church and state, with his involvement in the Christian event. The full name of the event was “The Response: A Call to Prayer for a Nation in Crisis.”

“I wonder if we had a Muslim governor, what would happen if the whole state was called to a Muslim prayer,” Kay Staley, one of five Texas plaintiffs, said in a story by The Associated Press.

Others had criticized Perry’s involvement with the group that put up the money for the event, the American Family Association. Originally formed in 1977 in Mississippi as the National Federation for Decency, the organization’s mission then was to target what it deemed to be anti-family television programming and pornography. Today, the AFA is more concerned with bashing the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population and their fight to obtain equal rights — a struggle much like that waged by blacks in the South in the 1960s. The Southern Poverty Law Center, which monitors the activities of extreme, violence-prone right-wing groups, has placed the AFA on its list of hate organizations in the United States.

Given the AFA’s pedigree, it’s small wonder that Perry’s invitation to the nation’s other 49 governors to join him in Houston basically flat-lined. Florida’s Republican Gov. Rick Scott sent a videotaped statement, but the only governor besides Perry who actually appeared in the flesh was Sam Brownback of Kansas. He read from the Beatitudes, a solemn blessing that marked the opening of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. Brownback then made a hasty exit stage right.

None of that seemed to matter, though, when, shortly after 11 a.m., Perry, unannounced, strode to the podium, looking like a male supermodel in a dark suit, red tie, white shirt, and perfectly coiffed hair. The standing ovation and visceral response that followed was of the kind usually reserved for rock stars and religious con artists. Giant video screens projected his image to people in the more distant seats; at the bottom of the screen, he was identified only as “Rick Perry” from Austin, with no mention that he just happens to be the governor.

Some of the faithful raised their arms heavenward. Others wept.

Outside the stadium there were tears as well — but mixed with a lot of sweat and shed in rage rather than joy. The 100 or so participants in the anti-Perry protest (mostly over the church-state separation issue) were the usual-looking rainbow coalition of suspects gathered on a sidewalk with no shade and nary a breath of air. Their dedication to their cause — and perhaps their need to seek mental health care — was magnified by their willingness and ability to withstand the wilting, 100-degree heat and nearly as high humidity, an inferno that would force even Satan himself to break a sweat. I don’t care if Hitler had come back from the dead and was sacrificing babies inside the stadium, you wouldn’t catch me out in that heat for long. (But if I do end up in hell, I can’t wait to see the look on the devil’s face when I tell him I’m from Houston.)

In the case of Katherine Jackson, her moisture was a mix of anger and heat. The slight 20-year-old Kansas resident, who traveled to the protest by bus, couldn’t hold back the tears as her soft voice exploded through a bullhorn beseeching her fellow protesters not to let Perry and his followers hijack their politics and their religion.

“My parents would like to retire, but they both have to work at Wal-Mart so they can keep me and them off the streets,” she raged. “People like Rick Perry don’t care about you. And they want to steal your religion. And they want to steal your government to have control over what you believe. But people like us are going to continue to fight.”

“My parents would like to retire, but they both have to work at Wal-Mart so they can keep me and them off the streets,” she raged. “People like Rick Perry don’t care about you. And they want to steal your religion. And they want to steal your government to have control over what you believe. But people like us are going to continue to fight.”

After her speech, I asked Jackson, sunburned and soaked with perspiration, if she thought Perry was hearing her message. She was realistic enough to admit that she doubted the protests would have any effect on Perry, but, she said, when it comes to patriotism you gotta do what you gotta do.

“I don’t know if he listens, because he has enough money that he doesn’t have to,” she said. “But hopefully somebody in there will hear us.”

But the protesters present on Saturday, many of whom, like Jackson, had traveled from across the country to display their disgust with Perry, were not alone in spirit. Earlier in the week, the Rev. William Lawson, one of the most respected members of Houston’s civil rights movement, publicly criticized the Perry rally for not only ignoring the constitutionally mandated separation of church and state, but also for holding what seemed to Lawson to be a racially and religiously exclusionary gathering aimed primarily aimed at white, conservative evangelicals. Lawson, founder and recently retired minister of one of Houston’s largest and most influential predominantly black congregations, gives few interviews these days but was moved to talk to a reporter this time.

Love Perry or hate him, on this day even some of the governor’s detractors and media skeptics had to hand it to the man. Often personally and politically tone deaf (firing handguns at political rallies or worse, firing his own parole board appointees when it seemed they were leaning towards clemency for a death row inmate), on this day Perry was pitch-perfect. He went out of his way to steer clear of controversy and politics. In a light-hearted moment that drew a lot of laughs, he joked that God was too wise to be affiliated with any political party.

Love Perry or hate him, on this day even some of the governor’s detractors and media skeptics had to hand it to the man. Often personally and politically tone deaf (firing handguns at political rallies or worse, firing his own parole board appointees when it seemed they were leaning towards clemency for a death row inmate), on this day Perry was pitch-perfect. He went out of his way to steer clear of controversy and politics. In a light-hearted moment that drew a lot of laughs, he joked that God was too wise to be affiliated with any political party.

Perry also made one impossible-to-ignore political comment. In an almost jaw-dropping moment during his brief sermon-like address to the overwhelmingly Christian crowd (although the event had been billed as open to all faiths), Perry closed his eyes and offered up a prayer for President Barack Obama and his family.

“Father, we pray for our president, that you impart your wisdom upon him, that you would guard his family,” Perry implored his savior. When he finished, Perry turned and bear-hugged the Rev. C.L. Jackson, a black Houston minister.

Perry’s words came off as sincere and heartfelt, a distinct contrast to the take-no-prisoners debate and demeanor that has ruled the national political scene recently and that just days ago reached a new heat level during the discussions, if you can call them that, over the national debt ceiling. In fact, all the speakers on Saturday played nice.

Other conservative national religious leaders shared the spotlight, most notably high-profile preachers such as Pastor James Hagee of Cornerstone Church in San Antonio. Even Grammy-winning bluegrass and gospel musician Ricky Skaggs made an appearance.

Perry’s words pleased supporters like Jim and Martha Wilson, 73 and 69 respectively, of the upscale Houston suburb of Kingwood.

“I was very pleased that it didn’t turn into a political rally, that we were here to praise Jesus and nothing else,” said Jim. “So I’m very happy with it.”

His wife Martha was more vocal, and her comments pointed up the fact that, regardless of what its organizers intended, politics were deeply intertwined with prayer at the event.

“I think we need a whole lot more of these [events] around this country because God is what’s going to heal this country, not these politicians,” she said. “I think what [Perry] did was absolutely fabulous, and that was to call people to prayer. I think this country is in a downfall,” she said. “We have to join together as Christians and try to help, not only through prayer but do what we can to get the right person, as they say, who has the fire in their belly to make the changes that we need in this country. … And God is going to be right there in the forefront for us. I think [Perry] would be a good candidate for president.”

Pastor Jim Parrish, 61, of the Burning Oak Baptist Church of Trinity, Texas, was even more direct about what he sees as a need for religion in politics. “I believe we need more godly leaders, and [Perry] was an example of that today,” said Parrish as he waited in line at one of the concession stands. “If we’re a nation that stands for God, we need leadership that is led by God.”

Yes, the concession stands did open in the afternoon — apparently it was only a half-day fast for lots of folks. Lines of as many as 40 to 50 people promptly formed. As people waited, musicians cranked out the unintelligible words to one Christian rock song after another, prompting many of the faithful to dance with their hands lifted heavenward. At some points, in fact, the crowd looked more like a terrible mixture of Dead Heads and Hare Krishnas than conservative Christians.

The governor seems to have heard the call of Parrish and others like him. Perhaps buoyed by The Response’s alleged 30,000 attendance and thinking about the campaign contributions that a crowd that large might produce, “Rick Perry from Austin” now appears poised to run for the top job in the nation that he once suggested Texas secede from.

The governor seems to have heard the call of Parrish and others like him. Perhaps buoyed by The Response’s alleged 30,000 attendance and thinking about the campaign contributions that a crowd that large might produce, “Rick Perry from Austin” now appears poised to run for the top job in the nation that he once suggested Texas secede from.

His performance Saturday may have gone a long way toward cementing Perry’s relationship with the evangelical Christian crowd, but he might do well to remember that not all conservative members of the Republican Party still believe in the flat earth theory. Only four and a half years ago, when Perry ran successfully for re-election, his Democratic opponent, former U.S. Rep. Chris Bell of Houston, whom the GOP had painted as being somewhere to left of the Son of Sam, reaped more votes in Perry’s politically conservative West Texas home county of Haskell by a 33 percent to 31 percent margin.

The joy at Saturday’s gathering was palpable. In the early hours of the event, the Rev. Luis Cataldo of Kansas City, Mo., excitedly reported to the crowd that the traffic on the freeway was lined up back to Hobby Airport. And I’ll give him that.

Indeed, my first encounter that day with the The Response actually occurred before I arrived at the stadium. Although it wasn’t a huge traffic jam by Houston standards, by 10 a.m. Saturday, event traffic was already causing backups in the westbound lanes on Loop 610 South at the Kirby Drive exit.

As I slowed to angle my truck toward the off-ramp, I couldn’t help but notice that dozens of drivers were zooming past me to get to the head of the line and then, in a very unChristianlike manner, forcing their way onto the exit ramp ahead of more patient and polite motorists.

So I avoided the Kirby exit altogether and instead sped over to the Fannin Street ramp where the backup was smaller. That way, when I muscled my way to the head of the line, I cut off fewer people.

Author and journalist Steve McVicker lives in Houston.