Last month, Fort Worth schools trustees voted to broaden the district’s antidiscrimination policy to include “gender identity and expression” for students. The change is designed to protect lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students from being bullied for expressing their sexuality in nontraditional ways, such as by boys wearing lipstick.

The board added similar language to its antidiscrimination rules for employees six months earlier, drawing praise from gay activists who say Fort Worth’s policy is now one of the most progressive in the nation.

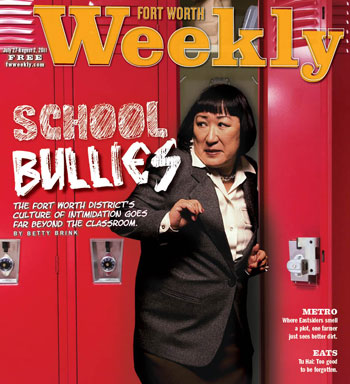

Policies, however, are just so much paper unless they are enforced. And in Fort Worth, according to dozens of employees, from maintenance workers to teachers and some administrators, bullying and intimidation for reasons other than sexual preference are so rampant and deeply ingrained that some workers have retired in order to escape it, while others have seen their careers stunted, their personal safety put at risk, or their mental health affected.

“Bullying is not always about sex or race,” said Sharon Herrera, the district’s former diversity and sexual harassment trainer. It is also about power, petty jealousies, and blame-shifting by incompetent supervisors to hide their failures, she said.

There is a culture of “fear and intimidation” in the district, she said, that has flourished in a system designed to keep employees in the dark as to their rights. An 11-year employee herself, Herrera said the district’s management culture is dominated by what she calls the “three ‘ates’ — humiliate, intimidate, and retaliate.” And it doesn’t stop with employees. Many teachers complained of witnessing the bullying of students by their co-workers.

There is a culture of “fear and intimidation” in the district, she said, that has flourished in a system designed to keep employees in the dark as to their rights. An 11-year employee herself, Herrera said the district’s management culture is dominated by what she calls the “three ‘ates’ — humiliate, intimidate, and retaliate.” And it doesn’t stop with employees. Many teachers complained of witnessing the bullying of students by their co-workers.

“It is the district’s dark, hidden secret,” said an employee who has suffered years of verbal abuse from a supervisor but asked not to be named for fear of retaliation.

On some campuses and in some departments, Herrera found, the abuses were so bad that many of those targeted told her they are on antidepressants, and some have even contemplated suicide. One employee told her that when he gets to work each morning, he sits in his car as long as he can, dreading the moment when he must go inside the building.

“Many are really broken,” she said. “This is what I saw and heard. No one should fear going to work so much that they consider suicide, especially in a public school system.”

Time and time again, Herrera said, employees who had the courage to speak up found that their letters and complaints — sent in some cases to the highest administrators in the district — went unanswered or were handled in such a way as to put them in even more danger of retaliation.

“In a school district, if we have chaos among the staff, we hand it to the children,” she said. “We should operate our schools on a foundation of trust, not a foundation of fear.”

Herrera should know. Her bosses, she said, sent her to a seminar at Harvard University on employee health and wellness issues including workplace bullying, encouraged her to build a district-wide program to combat bullying — and then, when they realized how many problems she was uncovering, threatened to eliminate her job. She was eventually moved to a position that had nothing to do with her expertise, leaving her program, if not dead, on “life support” said Larry Shaw, head of the United Educators Association, a North Texas education employees’ union.

“I’ve never worked in a place like this … I am in shock,” she said. “It is truly a toxic environment.”

At inner-city high schools here employees are usually under stress even at the best of times. But the past year definitely hasn’t been the best of times for one worker.

Rhonda has been with the district for several years, but this past school year, she said, was the worst period of her life because of a male superior’s unwanted sexual advances and district officials’ refusal to do anything about the problem.

Rhonda is not her real name. That information and the name of her alleged abuser have been withheld because she fears retaliation, like most employees who spoke to Fort Worth Weekly for this story. The employees all provided documents such as official complaints they had filed. In many cases, multiple employees told essentially the same story about a situation in their workplace. And investigators such as Herrera and representatives from UEA found their complaints to be true.

Rhonda started the year happy, she said, excited to be going back to a school where she liked working with the children. She had not encountered sexual harassment in the past.

Last year, however, she said, “things started changing.” In interviews with Herrera and complaints filed with the Office of Professional Standards, the investigative arm of the district, she reported that one of her male supervisors would suddenly appear behind her and grab her. Sometimes he would begin massaging her back. Soon he was touching her in “inappropriate places,” she reported. She resisted, but the abuse continued, escalating into violence. Once he grabbed her in the hall and pushed her so hard against the wall that her arms were deeply bruised. She took pictures of the injuries. He threatened to “hurt her” if she reported him. After months of hesitation, driven by fear of retaliation, she filed a complaint with OPS.

Besides her own case, she reported that she had witnessed verbal and physical abuse of the children at the school. In a letter to then-Superintendent Melody Johnson, she asked for an “immediate investigation to ensure that the bullying and harassment of the students stop” and that “you protect the children.”

The kids were called demeaning names by several staff members, she reported, and were yelled at and told that they stank. Some were refused lunch because their shirts were dirty.

In one of the most egregious cases, she reported that one employee, who was having a difficult time with one kid, yelled at him, “I fucked your mother all night while you were sleeping.” When the kid yelled back, the student was suspended, she said, for talking back to the teacher.

Statements like that might be hard to believe if documents from the Arlington Heights High School investigation had not been made public last August.

At that school, one coach’s vulgar verbal abuse of students and her fellow co-workers was well documented by dozens of teachers. They reported that former girls’ athletic director Izzy Perry was known to yell, “Get the fuck out of my gym” to students, as well as yelling at a fellow male coach to “Get the fuck out of my office, this is my fucking office.” Teachers complained about her providing graphic descriptions of her sex life, including oral sex, in front of teachers and students alike.

Before Herrera began providing diversity training — and before then-Assistant Principal Joe Palazzolo was appointed diversity officer, to receive their complaints — AHHS teachers said they had complained frequently to their principal, Neta Alexander, about many problems at the schoolonly to be ignored. An internal district investigation found the allegations to be valid. Alexander was forced to resign.

Rhonda and Herrera both said that nothing came of Rhonda’s complaints, other than Rhonda being told that, in a few weeks, she must report back to the school where her abuser still works. If the district insists on sending her back, she said she will retire rather than put herself in harm’s way.

OPS director Michael Menchaca has not responded to requests for comment on Rhonda’s complaints or to other questions raised about bullying in the district.

“Sharon [Herrera] was the only one who tried to help me,” she said.

In December, the school board adopted an anti-bullying policy for employees and students. Shaw, the UEA official, said the passage came after a major push by his organization.

The policy defines bullying as “repeated abusive mistreatment that undermines, humiliates, or threatens employees; prevents work from being done; and harms employee health.” Complaints to the union were increasing, he said, “so we made [getting the policy passed] our number-one priority.

“No question, bullying is widespread throughout the district,” Shaw said. “But this district is not alone.” The problem is getting worse in many areas, he said. “Teachers who run into conflict are usually scared to death and afraid to complain for fear of being fired.” Now those who are being picked on repeatedly have recourse, he said.

Shaw said that he did not believe Melody Johnson was a bully. “I think she was just not aware emotionally of the depth of the problem in the district,” he said. That won’t be a problem with Acting Superintendent Walter Dansby, he predicted.

“He’s aware, and he will do something about it. But this won’t be done overnight, not even by Walter,” he said.

“He’s aware, and he will do something about it. But this won’t be done overnight, not even by Walter,” he said.

Both Shaw and school board member Carlos Vasquez said that the diversity program under Herrera was successful and badly needed.

“Sharon should have never been pulled off of it,” Shaw said. “She’s very smart, very dedicated, and her talents are not being used where she is. UEA thinks she should be returned.

“The program is not dead,” he said, “but it is on life support.”

“It was working too well,” Vasquez said. “When [Johnson’s administration] saw how many people were coming forward, it became an embarrassment.” “So they tried to kill the program. … In a district as large and as diverse as this one, we need to learn that while we will not always agree, we must be tolerant and fair. Sharon’s program did that.”

Herrera holds a certificate in mediation and is trained in conflict resolution. After her first diversity training sessions, she found herself working with employees, helping them fill out grievances, and setting up mediation sessions to work out problems. They contacted her at all hours of the day and night. It was as if the floodgates had opened, she said, providing her with “deeply disturbing” evidence that bullying of employees was more widespread than anyone had imagined.

“I wanted to stop the injustices and change the culture of the workplace to one of inclusion, respect for all, and transparent dialogue,” she said.

Before coming to work for the district, she spent four years in the U.S. Air Force, then worked as a customer service manager with a grocery chain and as a service technician with a major telecommunications company, where she was the union steward for Communications Workers of America.

She began her career with the district as a teacher in 2000, was promoted up the administrative ladder until she found the job she says she loved in 2010: that of a diversity and sexual harassment specialist in the Employee Health and Wellness Department. In that role, she was chosen by now-retired Deputy Superintendent Pat Linares to develop and implement what the district called a “comprehensive diversity education program to promote a culture of inclusion for all employees and students.” There would be periodic training sessions to make sure employees were aware of the district’s policies and their rights and responsibilities under the law.

Using programs she designed, Herrera spent the 2009-2010 school year setting up diversity training workshops on campuses. Her job was to teach employees things like what constitutes sexual harassment, bullying, and a “hostile work environment” and how to file complaints and grievances, whether with the U. S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission or the district’s own Office of Professional Standards. She also provided mediation to resolve conflicts when possible.

Employees were assured by Herrera, who had been assured by Johnson, that their complaints would be held in strict confidence and that there would be no retaliation for reporting wrongdoing, she said.

She found, however, that neither of those statements was true. Complaints weren’t held in confidence. Victims of abuse were retaliated against. And over and over, district officials failed to address the problems that were reported.

At one school, a half-dozen teachers, with Herrera’s help, last year filed formal grievances against a co-worker whose abuse toward them has been going on for years, they said, and is well documented. The district dropped those grievances without comment. After that, the teachers filed charges with the OPS and EEOC. In those documents, the teachers said they were harassed, bullied, threatened, exposed to racist remarks, and stalked by the co-worker who had the protection of their principal, a close friend of the alleged abuser.

All the teachers who made the complaints have been with the district for a decade or more and have impeccable evaluation reports.

One worker said the alleged abuser spent eight hours on the porch and in the front yard of her home, trying to get her to come to the door and calling her constantly on the phone, following a dispute at work.

“It was frightening,” the teacher said. “I felt I was being stalked and threatened. Still, I was told by my supervisors that nothing could be done.”

Another of the six said that the abusive co-worker had frequently called her at 3 a.m. to berate her for things that had occurred at staff meetings.

One of the most serious charges was that the alleged abuser had shared very personal medical information about one teacher with other co-workers, which could be a violation of federal medical privacy laws.

The teacher whose information was spread around felt betrayed, he said, and added his name to the EEOC complaint.

The teachers said their abusive co-worker frequently made racist remarks, including use of the n-word. Several reported hearing her say “N—–s think they are equal to us, but they aren’t.”

The group said one co-worker has been targeted more frequently than anyone else and that the alleged abuser had told that co-worker frequently to “shut up” in staff meetings.

“She has demeaned me before others and suggested, without cause, that I needed observation and intervention. I was crippled by her threats that she could have my job if I did not comply with everything she said,” this teacher said. “I knew she was close to the principal and feared she might be able to do that.”

The group was initially told by Menchaca that the accused was guilty of “maliciousness, manipulation, and calculated sabotage,” one of the teachers said, but that the district’s hands were tied. The complaints were dropped by OPS without any of the complainants being interviewed, another teacher said.

“We were told by our supervisor that the case was closed, and we were not told why. We were told to drop it, not mention it again, and to not ask questions,” one said in an interview.

“There was no investigation,” another teacher said, in spite of the fact that the allegations all fall under prohibited behavior in the district’s policy manual.

“This is a case of one person being able to bring chaos to a whole group,” a third teacher said. “We are deeply disturbed that nothing was done.”

Herrera heard complaints throughout the district about workers and students being called racist names to their faces.

A Hispanic employee said he was told he was lucky to have a job because he was a “burro,” she said. An African-American student recounted that he was told, “N—s get out of my gym.”

That kind of language is nothing new to the group of maintenance workers who have filed complaints against bullying by a supervisor who, they say, uses the n-word regularly in spite of the fact that there are many blacks in the department. In their complaints, the workers said the supervisor’s boss encourages his behavior and does nothing to stop it.

In interviews, the men told the Weekly that it was common in their department for the supervisor to curse them with vulgar and offensive racial language. The workers said the supervisor consistently uses the phrase “you foreigners” to refer to the men and women from various Central American countries who work for him, even though they are legal citizens.

Most of the men have been with the district for years, and all have good evaluations. In one recent complaint, a younger worker stated that the supervisor “continues to belittle me” in staff meetings, “embarrasses me and humiliates me all the time.” The other workers backed him up. They praised the young man as one of the most dependable workers in their department, and yet, they said, he seems to be a particular target of the supervisor.

Most of the men have been with the district for years, and all have good evaluations. In one recent complaint, a younger worker stated that the supervisor “continues to belittle me” in staff meetings, “embarrasses me and humiliates me all the time.” The other workers backed him up. They praised the young man as one of the most dependable workers in their department, and yet, they said, he seems to be a particular target of the supervisor.

The men said they and others were particularly offended by a decal the supervisor posted on his locker, bearing a quote from Adolph Hitler about taking guns away from German citizens. They said it was removed only after a grievance was filed.

After these men filed their first grievances with the district — grievances that were supposed to be kept confidential — they were marched into an office right next to the supervisor’s to be interviewed.

“He saw each one of us, knew how long we were in the office with the investigator,” one worker said. “How hard was that for him to know who we were?”

The grievance process was “shut down,” another man said, and afterward the bullying intensified.

All of the men interviewed said their health has been affected. They are all taking antidepressants, they said, in order to get up in the morning and go to work. One has asked to be transferred to another department, a move that his co-workers say, will diminish the quality of the work in their own department because of the loss of his skills and experience

Don Mathis, an employee representative with UEA, told the Weekly that the organization is representing one of the men after finding that his complaints have merit. “There is a long history of this type of bullying in this department, a history of unequal treatment, abusive talk to employees, and a fear of retaliation,” he said.

Complaints have been filed before only to go nowhere, Mathis said. But this time, “I think this is a good case, and that things will soon change for all of them.”

The emptiness of the school district’s promise of confidentiality and protection from retaliation for those who report abuses was made clear last year at Arlington Heights High School, after Herrera conducted a diversity training session there.

Then-principal Alexander had appointed her new assistant principal Joe Palazzo as the campus diversity manager.

After the training, dozens of teachers and coaches brought complaints of serious wrongdoing to Palazzolo. He in turn reported them to Herrera and to OPS. The result: Palazzolo was soon demoted and ultimately fired in spite of the fact that a months-long district investigation upheld all of the allegations.

His case would ultimately have a chilling effect on employees’ willingness to come forward to report complaints. But before that happened, Herrera was overwhelmed, she said, as employees came out of the woodwork with abuse complaints, believing that the district was finally serious about protecting their right to work in a nonthreatening environment.

“When word got around, employees would come to my office and let down,” she said. Soon, just about every employee knew her name, she said, from the cafeteria workers to those who worked in the highest offices of the administration.

Many told her they had given up on filing complaints or grievances as most of them were simply ignored or were dismissed as unsubstantiated.

“Filing a complaint is a joke,” one disgruntled employee told the Weekly.

One of the problems with the system, Herrera said, is that an abused employee must first file a complaint with her or his supervisor, who is often the abuser. If the grievance receives any attention at all, then a months-long hearing process follows. In the meantime, the employee must continue to work under the very person he or she is complaining about.

“It’s a very unfair system,” Herrera said. There should be an office that reports directly to the superintendent, where employees can take their concerns in strict confidence, she said.

But Herrera would not have a chance to pursue that idea. In early 2011, Chief of Administration Sylvia Reyna sent word that Herrera’s job was targeted for elimination by the board in a cost-saving move. Herrera was transferred to the department of student engagement, where she sets up school-sponsored events for students.

She is no longer involved in the work that is her specialty, in spite of the fact that she has dozens of pages of positive statements from employees, including principals, who went through the program. Many asked that the program be continued on an annual basis. She still hears from employees asking for help, which she gives, she said, meeting them on her own time.

Board members Ann Sutherland and Vasquez both said that, as far as they know, the elimination of Herrera’s diversity job was never discussed with the trustees.

Herrera, however, was not surprised by the move. She had testified in Palazzolo’s appeal hearing that she felt his firing was retaliation. She also testified that as a witness for Palazzolo, she feared for her job.

She and others believe that the Palazzolo controversy brought down the diversity program.

“The district was not serious at all about that program,” said Linda LaBeau, a mediator for families of children with disabilities, who ran unsuccessfully for the school board in 2010. “It was just something to make the administration look good, until Palazzolo and those teachers at Heights took the district seriously that it wanted to do the right thing,” she said, “and look what happened to him.”

Herrera and others interviewed for this story said that Johnson, in her six years of leading the district, did little to rein in some of the out-of-control people who worked for her and had the reputation of shutting her door to employee complaints. She could not be reached for comments for this story.

However, those who worry about the district’s current “culture of intimidation” are cautiously optimistic that interim superintendent Dansby will usher in a healthier era. The 37-year veteran of the district was appointed in June to temporarily replace Johnson while the board conducts a national search for a new superintendent.

There are some, however, who say that such a culture of bullying could not have gone on so long without his knowledge.

Dansby was on vacation this week and could not be reached for comment. But in an interview just a few days after his appointment, he told the Weekly that he was aware of and deeply concerned about the bullying allegations and intends to look into each one. He said as far as intimidation and retaliation are concerned, he intends to “change the culture,” emphasizing that his door would always be open to employees.

Mathis, the UEA representative, has worked with Dansby for many years. He said that when Dansby was made aware of problems within one of his departments, he took care of them. “Walter is not going to support wrongdoing, anywhere,” he said. “If he knew something was wrong and he was in a position to do something about it, he did.” Many of the complaints under Dansby’s supervision were settled at the lower level, he said.

“The change in the leadership of this district is going to make a difference,” Mathis said.

One employee who spoke to the Weekly for this story has already met with Dansby to tell him her complaints. Afterward, she was encouraged that he listened and promised to look into her problems.

Nonetheless, she is fearful that the abusive culture has become so institutionalized that it may take more years than Dansby has to undo the damage and build trust among the employees again. “I know as each day draws nearer to opening day, all of us are feeling the anxiety of returning to a place of tension and hostility,” she said. “If nothing can be done, then all I want is a straight up answer — why?”