What a difference a decade makes. It was about that long ago that that the Tarrant Regional Water District and City of Fort Worth gave the go-ahead to what would become the Trinity River Vision, an ambitious project intended not only to improve flood control but literally and figuratively to reshape the land north of downtown, creating a lake and canals and turning an old industrial area into a sparkling extension of the center city, with high-rise buildings overlooking a riverwalk and waterside amenities.

The project drew little opposition at first — until landowners realized that the government could take their properties by eminent domain or its threat and eventually sell them to some other private developer, in the name of economic development.

A flood-control-only project could have been done for as little as $10 million, according to federal estimates, but it looked like there would be plenty of backing from Congress and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, as well as the city and water district, for the $225 million or so it would take to re-engineer the river, including better levees, a 1.5-mile bypass channel, and fancy bridges.

A flood-control-only project could have been done for as little as $10 million, according to federal estimates, but it looked like there would be plenty of backing from Congress and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, as well as the city and water district, for the $225 million or so it would take to re-engineer the river, including better levees, a 1.5-mile bypass channel, and fancy bridges.

The economy was robust, the Corps was handing out lots of money to governments for pork projects around the country, and most locals were OK with Fort Worth getting in line in Washington with its hand out.

Things look a lot different these days. Projected costs for the project have ballooned to about $909 million. The economy is still in the Great Recession, and federal, state, and local governments are all facing severe budget shortfalls that will leave their mark for years to come. Congress has put a temporary ban on earmark bills, the strategy by which local project funding was routinely added to unrelated bills and that U.S. Rep. Kay Granger of Fort Worth used to get about $60 million for the TRV in the past. And the Corps, faced with continuing fallout from the Hurricane Katrina debacles in Louisiana and this year’s massive flooding along the Mississippi, is dealing with many projects much more critical than improvements in Fort Worth to a river section that hasn’t seen significant flooding in half a century.

As funding has retreated, the tide of local resistance to the project has strengthened. Some are questioning now whether the TRV project will improve flood controls at all — and suggesting that it might even weaken them. Private property owners are facing years of uncertainty over if and when their land will be taken.

But no one has shut the bulldozers off. Property is being bought, buildings are being torn down, and dirt is being hauled away — even while serious questions are being raised about where the money will come from to complete what has been started.

“Times have changed dramatically since this project was first proposed,” said local attorney Bob Gieb, who lives in the Oakhurst neighborhood just northeast of downtown. “We have overspent ourselves into serious problems, both on the national and local levels. We are at a point where we have to reassess priorities.

“In this climate, the taxpayers should not be paying their hard-earned money so that private businesses can make more money,” Gieb said. “We have to have some governmental control over projects like this. And the way the Trinity River project is structured, I see no governmental control. When the citizens ask questions, we get no answers. No wonder the costs have risen so much.”

“In this climate, the taxpayers should not be paying their hard-earned money so that private businesses can make more money,” Gieb said. “We have to have some governmental control over projects like this. And the way the Trinity River project is structured, I see no governmental control. When the citizens ask questions, we get no answers. No wonder the costs have risen so much.”

The Trinity River Vision Authority is the governmental agency created specifically to oversee this massive project, but the officials on its governing board are appointed, not elected by the public. Board members represent county government, the water district, and Fort Worth, among other entities. The regional water district, whose board is elected, is responsible for assembling land for the project. The state is supposed to kick in transportation-related funding, and the Corps is playing a key role, only one of many federal agencies involved.

This has created a hodge-podge of responsibilities. Repeatedly, during research for this story, Fort Worth Weekly’s questions were referred from one agency to another. Then another. And another. Private citizens are finding the same experience.

“We show up at meeting and ask questions and rarely get any real answers,” said one neighborhood leader who didn’t want her name used. “And what really gets people mad is that the outcome … seems to be predetermined.”

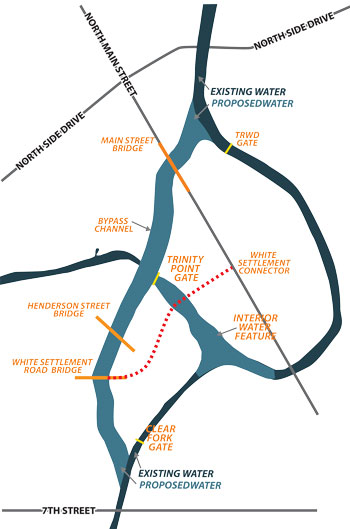

One example is the planned use of Riverside and Gateway parks for flood retention downstream from the bypass channel. The channel is a key — and quite controversial — part of the plan. The 300-foot-wide channel will run a mile and half, beginning where the West and Clear forks of the Trinity merge just west of downtown. While the river course bends south to run under the bluffs by the Tarrant County Courthouse and curves north again below Samuels Avenue, the bypass channel will arc north and east, rejoining the river just north of LaGrave Field.

The Corps has said that the bypass is needed for flood control and that it will move floodwaters more efficiently. However, its main purpose is to allow that U-shaped section of the Trinity to be kept at a constant level, creating a town lake where levees can be removed and development can come down close to the water level. Floodgates would control water flow to that portion of the river. The bypass would create two large islands that would be crisscrossed with canals.

But the channel also means that floodwaters will be diverted into a shorter waterway. To replace lost flood capacity along the U-shaped stretch and to add more, the city has had to designate flood retention areas. The TRVA’s original plan was to reconfigure the Trinity River upstream on the west side for flood storage, using a part of the river near the Rivercrest Country Club. But wealthy private property owners threatened to fight the plan in court. The Corps then decided that Riverside Park and the 500-acre Gateway Park farther downstream to the east — and next to more modest and less powerful neighborhoods — could be used instead.

“With the Corps’ plan to redirect the river through the parks, and with the creation of flood retention lake and ponds within the parks, the hydraulic engineers think there will be less flooding after the bypass channel is built,” said J.D. Granger, executive director of the TRVA and son of Kay Granger, who has led the drive for TRV for more than a decade.

But those opposed to the project disagree vehemently. “We don’t have a flooding problem in the areas just north of downtown now,” said former Fort Worth city council member (and unsuccessful water district board candidate) Clyde Picht. “These parks get a little flooding every now and then, but nothing like you will see if the bypass channel is built. It is just basic engineering. Move water into a more compact and shorter waterway, and those downstream will get more water coming their way.

“What is driving this is the business and real estate interests who want economic development funded by the taxpayers,” Picht said. “But what makes a lot of people angry is that they are pushing flooding downstream to the east, to neighborhoods that don’t have the same political clout as the downtown business interests.

“What is driving this is the business and real estate interests who want economic development funded by the taxpayers,” Picht said. “But what makes a lot of people angry is that they are pushing flooding downstream to the east, to neighborhoods that don’t have the same political clout as the downtown business interests.

“The fact that they have to make two public parks [into] a place where they send their excess water is disturbing,” Picht said. “And the fact that they need to dig a big hole at Riverside Park indicates they know this is true.”

That means destroying a portion of Riverside Park and recreating it as a much lower terrace that would be covered with floodwater from time to time and creating flood retention basins in Gateway. As part of the deal to win the support of surrounding neighborhoods, the city says it plans to build more baseball and soccer fields, expand the trails, and maybe even add a 6,000-seat amphitheater and equestrian center in Gateway. City staffers have said in neighborhood meetings that they expect the federal government to pick up half the expense –— but there isn’t even a formal estimate of how much that work would cost, much less a commitment from the federal government to pay for it.

J.D. Granger said that moving the flood retention area from the West Side to the East Side was a factor in increasing the project cost.

“We needed the flood storage capability, and the Corps suggested we could use this park property and then, as part of the plan, make it a real destination park, something Fort Worth desperately needs,” he said.

TRV officials are vague about how the parks redo would be paid for. The city’s portion could come from the gas leasing revenues on city parkland. Due to environmental problems (both parks are former industrial areas), some funding might come from the EPA.

The issue of these two parks has divided Eastside residents. Janice Michel, a longtime resident of the Oakhurst neighborhood, said she likes the park improvements that would happen as part of the TRV.

“This is not just going to be a hole in the ground,” Michel said. “We’ll have better trails and lighting and more soccer fields, and the park will be used more. We were able to get 800 signatures on a petition supporting changes at Riverside. I feel the community really backs this plan.”

“This is not just going to be a hole in the ground,” Michel said. “We’ll have better trails and lighting and more soccer fields, and the park will be used more. We were able to get 800 signatures on a petition supporting changes at Riverside. I feel the community really backs this plan.”

Gieb disagreed. “They came to our neighborhood three or four times and asked us to decide if we wanted to do this,” he said, and each time the neighborhood turned down the idea. “Then they would change the rules and not listen to us.

“They did this in Riverside Park because they didn’t want to fight the rich folks on the West Side,” Gieb said. “They didn’t want it challenged in the courthouse because more information would be made public through the lawsuits. And the one thing I’ve found out about dealing with this project is that real, hard facts are hard to come by.”

The federal funding component of the TRV is now $487 million of the $909 million. That includes the Corps’ flood control work, along with contributions from federal transportation, economic development, housing, and environmental protection agencies.

In the convoluted world of Washington, as in Fort Worth, it is hard to get clear answers on where the Trinity River Vision stands. The Corps has ruled that the project is “technically sound and environmentally acceptable,” but the funding must be approved on a year-by-year basis. In the past five years, about $29 million has been appropriated for it. But that is nowhere near the Corps’ $466 million price tag to finish it.

Still, the TRV is busy buying property (using the Tarrant Regional Water District as its agent) and moving dirt.

Economic conservatives are questioning whether the TRV will ever provide the economic boom that is being touted and whether the city can afford such an ambitious project.

“I think this is becoming a bait-and-switch plan, something private businesses would be prosecuted for if they did it,” said Steve Hollern, a local accountant and former chair of the Tarrant County Republican Party. “What the TRV is doing is buying property, tearing down buildings, using eminent domain, and having very little chance of getting the federal funds they need to complete it.

“[The TRV’s] plan in my opinion is to start work on the new bridges and the bypass channel, and if the federal money doesn’t come along, just tell the citizens of Fort Worth we are too far along to stop,” Hollern said. “Then the local taxpayers will have to pick up the cost, and they can do that through increases in water fees or putting the city in debt with bonds.

“The best thing we can do now is put the project on hold for a few years while the federal government sorts out its funding issues,” he said. “Because as it stands now, [the TRV] looks to be a failed project of massive proportions.”

Granger wholeheartedly disagreed. “I am not concerned about the federal funds drying up, because this is primarily a flood control water project, and those have been a top priority in Washington,” he said. “This is not a short-term solution to flooding issues on the Trinity River, but a long-term plan that solves a very real problem.”

Continuous urban development north and west of Fort Worth, with more and more land being covered by concrete and other impervious surfaces, results in more upstream water rushing into the river channel and less being absorbed along the way. “We have to find a way to push higher volumes of water through the river systems in a more efficient way,” he said.

Granger said economic development is the key to local funding. “Private developers are not going to invest in this part of Fort Worth, because the properties are in a flood plain, and these developers are not going to take that kind of risk,” Granger said. “But once we solve the flooding issues, we will see long-term economic growth, and that growth will help fund a needed flood control project, give citizens access to a river they never had, and even make money for the local governments.”

Granger said economic development is the key to local funding. “Private developers are not going to invest in this part of Fort Worth, because the properties are in a flood plain, and these developers are not going to take that kind of risk,” Granger said. “But once we solve the flooding issues, we will see long-term economic growth, and that growth will help fund a needed flood control project, give citizens access to a river they never had, and even make money for the local governments.”

Opponents have gotten more traction in recent years, mainly due to the economy. A group called the Trinity River Improvements Partnership (TRIP) has been holding meetings, usually with a few hundred people in attendance (a big crowd for Fort Worth local issues), advocating an alternative plan that would include many of the TRV levee improvements and creation of a town lake, for about $60 million.

But opposition has not translated to change at the ballot box. When Jim Lane and Marty Leonard ran for re-election to the Tarrant Regional Water Board last year, they easily beat two candidates who based their campaigns on ending the project. Fort Worth mayoral candidate Cathy Hirt publicly called for stopping the TRV, but she did not make the runoff in the race last month.

Lane and Betsy Price, who will meet in the runoff election this week, have both been adamant supporters of the TRV.

“There are a number of opponents to this project, but they are very much in the minority,” Granger said. “Most citizens of Fort Worth I talk to see value in this project. It will change this city in so many ways, all of them for the better.”

The schedule for the Trinity project is already slipping. When planners decided the bypass channel needed to be wider than originally drawn, that forced a redesign of three bridges over it, all of which require local, state, and federal funding. Work is scheduled to begin on the Henderson Street bridge next year, followed by White Settlement Road two years after that. The Main Street bridge will not be completed until about 2017.

About 95 private properties have to be acquired, which is being handled by the Tarrant Regional Water District. The water district estimates that land acquisition, demolition, and relocation of property owners will cost $226 million.

That figure is somewhat deceiving. The money will actually be a loan to the TRV based on future city property tax revenue. That revenue would come from a tax increment financing district (TIF), created for the 800 or so acres covered by the TRV. Such taxing districts freeze property tax revenues at the level current when the TIF is created; as property values within the district rise, the additional tax dollars stay within the TIF to be used for infrastructure projects.

Those infrastructure projects could include roads, sewer lines, stormwater system improvements, streetscapes, and other accoutrements. The TRV wanted to use about $40 million in TIF funding to pay for a modern streetcar line to the project, but that was quashed by city council earlier this year.

With the TIF operating, why does the water district need to lend the river project authority $226 million? Because the TIF will not realize the revenues from property tax growth for many years. (TIFs previously were authorized for 25 years, but a change in state law two years ago extended their existence to 40 years — on a vote of the TIF board itself.)

In all, $320 million has been budgeted from the TIF for the project. An economic study paid for by TRV Authority and the water district estimated the TIF will bring in $440 million over the 40-year time frame, more than enough to pay off the water district loan and the $100 or so million in infrastructure improvements needed.

“The local commitment is important, and that is part of the reason I am not worried about the federal funding,” Granger said. “Federal funding for projects like this are based on local economic commitments, and we have that. And our economic models, which are conservative estimates, [show] enough to pay our local share and still have enough left over to put in the city’s general fund.”

The economic study also indicated that 10,000 new housing units would be created and 16,000 new jobs (that would be 400 a year). The tax base is projected to increase by $1.3 billion over the 40-year life span of the TIF. “The Fort Worth Independent School District is not part of the TIF, so their increase in revenues will be huge,” Granger said.

But some question whether these figures have been inflated in order to keep the various government agencies and the local citizenry on board.

“I can’t see how they will be adding 400 jobs a year, even if the economy improves,” said Picht, who thinks the city should just halt the project altogether. “TIF funds are still public tax dollars, and they keep money out of the city budget that [could] pay for basic city services.

“We have road projects that cannot be funded, we have community centers closing, and we cannot keep our public pools open,” Picht said. “TIFs for the most part in this city have been a failed policy, just a way to transfer hard-earned taxpayer dollars to influential private businesses and developers. Based on what I have seen on [the TRV project], this one is no different. And I doubt they will get the funding they need for the basic infrastructure, even over 40 years.”

Owners whose property is clearly in the path of the project have been left in a peculiar situation: It makes no sense for them to develop their property for their own uses, and they wouldn’t be able to sell it to other buyers — but the government agencies might not buy them out for years.

Barry Rubin’s family has run American Auto Salvage on Henderson Street since 1935. The company buys wrecked vehicles, takes out the functional parts, and sells them to other companies.

Despite years of negotiations, the water district and Rubin couldn’t agree on a purchase price for his approximately seven acres. The water district then condemned the property and used eminent domain to acquire it for about $2.4 million. Rubin moved his company just north of the Stockyards — and sued the water district in federal court over the price he was paid for the Henderson Street property.

Despite years of negotiations, the water district and Rubin couldn’t agree on a purchase price for his approximately seven acres. The water district then condemned the property and used eminent domain to acquire it for about $2.4 million. Rubin moved his company just north of the Stockyards — and sued the water district in federal court over the price he was paid for the Henderson Street property.

“When I look at what other property owners got in this area, I just don’t think we were treated fairly,” he said. “We didn’t want to move in the first place, and we often wondered why we had to do it at this time when the bypass channel probably won’t be built for a decade, if at all. But we never could get an answer to that.”

Purchase prices for TRV land are all over the map. Rubin received about $7 a square foot, while the water district paid other landowners up to $30 a square foot. Some prices were well above the value set by the Tarrant Appraisal District.

Case in point: the shuttered Pit barbecue restaurant at Henderson Street and White Settlement Road. The district bought the one-third-acre property last year for $286,000, or about $17 a square foot. TAD had it valued at about $130,000.

Water district spokesman Chad Lorance said no district official would comment about land purchase policies. The district did provide a list of 24 transactions that have been completed during the past few years, totaling about $35 million. The funds (part of the loan to the TRVA) have come from the water district’s oil and gas lease funds.

Of those 24 transactions, four used eminent domain, including the American Auto Salvage purchase, for a total of about $11 million. The water district identified five more properties last month that will be acquired through eminent domain.

Lorance did not include the 41 acres of land around LaGrave Field purchased from Fort Worth Cats owner Carl Bell last year for $17.5 million. “The properties surrounding LaGrave were purchased to address interior flood control, stormwater run-off, and associated environmental issues that TRWD will be addressing outside the federal project,” Lorance said. He would not elaborate.

Matt Miller, executive director of the Texas chapter of the Institute for Justice, said he expects to see plenty of misuse of eminent domain in the Trinity project. “There is no doubt in my mind there will be property taken for use in private development,” he said. “Tax dollars will be used so that condo developers can do their developments cheaper.”

One of the ways the water district will get around legal limitations on the use of eminent domain is through the design of the project. Eminent domain is supposed to be used only for public uses, and the bypass channel itself qualifies on that score. But the plan also includes canals, storm utility construction, and other utility relocation that crisscross the property — which means that virtually all the 95 or so parcels could, if needed, be acquired through eminent domain because of those public uses.

Jimmy Vreeland, president of Vreeland Construction, lost his property on West Vickery Boulevard to the city in 2006 through eminent domain condemnation for the Southwest Parkway. The process was supposed to take one year but instead took seven. He moved his business to the North Side, only to find himself in the path of the planned bypass channel.

Jimmy Vreeland, president of Vreeland Construction, lost his property on West Vickery Boulevard to the city in 2006 through eminent domain condemnation for the Southwest Parkway. The process was supposed to take one year but instead took seven. He moved his business to the North Side, only to find himself in the path of the planned bypass channel.

“The problem I have is being in limbo,” Vreeland said. “I can’t move to a new property, because no one will buy the old one. And I can’t afford two properties. So I don’t make repairs on my building and just wait. And given the uncertainty of funding problems for Trinity River Vision, I’ll probably be in limbo for a long time.”

Bob Lukemon owns a photography studio on White Settlement Road that also lies in the path of the bypass channel. He has not received an offer either. He likes his studio property and his location close to downtown. And he has problems with public money being used to buy out private businesses for the benefit of private developers.

“I have thought a lot about the use of eminent domain to accomplish this project,” Lukemon said. “The business and real estate community has such an overconfident image of the benefits of the project. … The ratcheting down of private property rights in this rush to promote the profit potential of this project is alarming to me and should be to every true conservative. When greed trumps our rights, and our politicians help ignite the greed fire with their promises to the business community, one has to wonder who they serve.”

Lukemon and others hired an engineer about five years ago to come up with an alternative plan for Trinity River flood control. Under this scenario, no bypass channel would be constructed. Instead, levees would be moved farther away from the river and raised, providing space along the river for trails and walkways while keeping basically the same plan in effect for flood control. That plan would also create a small town lake. Private development would be left to market forces. Total estimated cost is about $60 million.

Granger said he has looked at the alternative plan and that it is fraught with errors. Taller levees would require wider bases, he said, making it necessary to acquire private property. “There is also no way the Corps would approve this plan, because it does very little for flood control,” he said.

Lukemon wasn’t impressed. “J.D. really thinks the [alternative] plan takes private land? That is typical of the systematic misrepresentation of the plan as characterized by the project promoters. Mayor Moncrief referred to it as a scam. I guess if people don’t study the plan, they will just let these leaders make the judgments.”

If Lukemon and lots of others in Fort Worth have questions, local politicians don’t seem to. Asked whether the project should be put on hold until the federal funding is firmed up, they gave responses almost as vague as those from the government agencies.

“I’ve said all along we need to look at it a piece at a time,” said Price. “We need to meet with Kay Granger and the water district and see where it stands. We will have to take a hard look at it, but that’s what we should do with every government project.”

City council member Sal Espino, whose district includes the Trinity River Vision project, said he supports the project “in principle” but acknowledged that more and more people are getting worried about federal funding. “I share those concerns particularly in light of the political environment in Washington which aims to curtail spending,” he said.

U.S. Rep. Granger passed the buck. Her spokesman, Matt Leffingwell, said in an e-mail that the Weekly should direct its questions to the TRVA “since these are really questions about the management of the project. However, I can say this on the record: Congresswoman Granger will continue to work with federal, state, and local partners to secure funding for this important flood control project.”

Which brings the issue back to the private property owners who are at the center of the debate. Most of them seem a little more realistic.

“I am not adamantly opposed to this,” said Rubin, the salvage company owner. “It could be a nice addition to the city. But the reality of the situation is that we as a city and county cannot afford these types of projects right now. I don’t think it will ever happen.”