Awell-worn footpath leading through a patch of weeds into a large stand of trees is the only sign that you’re approaching a homeless camp on Fort Worth’s East Side. Low-hanging branches and bushes have been left untouched to help conceal the spot from outsiders.

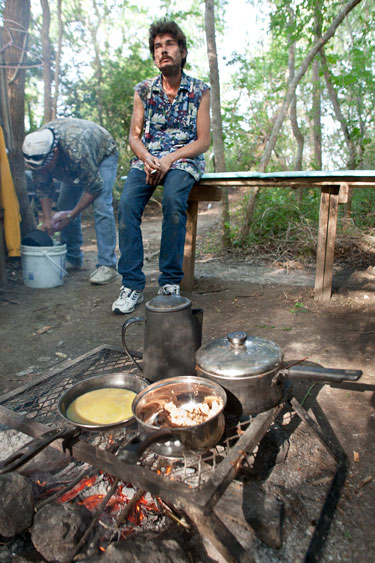

About 100 feet in, the trail ends at a tiny warren of seven or eight tents around an open area defined by two long benches flanking a small fire pit with a grill. A kitchen counter rigged between two trees is covered in bottles and jars of condiments and instant coffee; shelves underneath hold pots, pans, and soap. The bathroom is a squat hole dug into the ground 20 feet away. A piece of paper taped to a tree nearby reads: “Paper in the basket please. Thank you.” Shower and laundry facilities consist of the nearby Trinity River. The camp is in a beautiful spot, surrounded by trees and bluffs, and residents keep it neat and garbage-free. If you were just camping for a couple of weeks, it would be a prime site.

About 100 feet in, the trail ends at a tiny warren of seven or eight tents around an open area defined by two long benches flanking a small fire pit with a grill. A kitchen counter rigged between two trees is covered in bottles and jars of condiments and instant coffee; shelves underneath hold pots, pans, and soap. The bathroom is a squat hole dug into the ground 20 feet away. A piece of paper taped to a tree nearby reads: “Paper in the basket please. Thank you.” Shower and laundry facilities consist of the nearby Trinity River. The camp is in a beautiful spot, surrounded by trees and bluffs, and residents keep it neat and garbage-free. If you were just camping for a couple of weeks, it would be a prime site.

The man who put the camp together is called Little Wolf, a 22-year-old who says he never knew his mother, has a dad in prison, and was raised by his older brother. He’s slight and shy, a bit wary. But he lights up when asked about the camp.

“Me and my boy built this,” he says proudly, referring to a close friend. “We was living in Tent City over on Lancaster and Riverside” — a former camp that held as many as 80 tents before the police forced everyone out in late January — “and then we came here and found this place a few months ago.”

In wooded areas throughout Fort Worth, but primarily in the vicinity of East Lancaster Avenue, there are dozens of well-hidden camps that hundreds of people call home. At the best of them, small groups of residents who’ve become friends keep their campsites clean, share chores and expenses, and in at least some cases work on getting back into jobs and houses and mainstream life. At the worst of them, drug and alcohol use is rampant, and violence is all too common. And in many of the encampments, residents have no serious intent of changing their status: They like it there.

If you’re used to the freedom of camp life — doing what you want, when you want — the shelters aren’t appealing. If you’re an active alcoholic or drug addict, the shelters are simply an impossible alternative.

The camp residents say they’re hurting no one and wish the authorities and others would leave them alone. But those who live or run businesses nearby say the camp denizens create serious problems. In the East Lancaster area, the camps add another level of worry to a neighborhood already carrying the weight of most of the city’s homeless people and the agencies that serve them.

When the homeless who stay in organized shelters go into those facilities for the evening, said Suzette Watkins, owner of Riverside Kennel, it’s the campers who “are involved in the alcohol use and drug selling along East Lancaster at night.” She sees them each morning, coming out of the camps and heading into the neighborhood.

When the homeless who stay in organized shelters go into those facilities for the evening, said Suzette Watkins, owner of Riverside Kennel, it’s the campers who “are involved in the alcohol use and drug selling along East Lancaster at night.” She sees them each morning, coming out of the camps and heading into the neighborhood.

“Just having them around makes people not want to come to my kennel,” she said.

Either helping or hurting the situation, depending on your point of view, are the individuals, churches, and a few other groups that enable the camps to survive by providing food, supplies, tents, and various kinds of support to those who don’t want to go to the shelter agencies.

The Abbey Church in Azle started a homeless outreach program last year called Heaven’s Resources. Its managing director, James Buckley, and his wife Jennifer provide food and other supplies to camps regardless of their conditions.

“A lot of people don’t want to serve people who are buying drugs, buying alcohol, but we disagree,” said Jennifer. “You love on people. We don’t put conditions on the camps or people. They are our friends.”

In recent years, the city has changed its method of dealing with the homeless problem: The emphasis now is on the kinds of help needed to get people back into jobs and homes and self-sufficiency, rather than simply providing ever more sandwiches and shelter cots.

“The churches’ motivation [for helping the campers] is beautiful,” said Otis Thornton, Fort Worth’s homelessness program director. “But at what point does meeting those fundamental needs perpetuate homelessness? You don’t want to foster their life outdoors by making it really easy. But then their lives are already really hard … Where’s the line?”

Sustaining the camps and the people who live in them is a hard, expensive, and time-intensive job. James Buckley estimated that there are more than 70 of the camps hidden throughout the city. His group works with five of them, where a total of about 40 homeless men and women congregate.

Buckley’s outreach program receives almost all its funding from his church’s generous congregation — about $1,200 a month is needed to support the mission. But that mission is always growing, he said. Currently, Heaven’s Resources provides the campers with about 2,000 pounds of food monthly, along with tents, sleeping bags, tarps, clothing, transportation, bus passes, counseling, and ministry.

“We are the safety net,” he said. “We catch what falls between the cracks.”

Catholic Charities of Fort Worth also works with the unsheltered homeless, through its Street Outreach Service or S.O.S. The program aids people living on the street, in campsites, or anywhere “not meant for human habitation.”

Rick Paredes believes in what those groups are trying to do but feels their resources would be better spent focusing on a few homeless who really want to change. “Take a handful of people who want that hand up,” he said. “That’s how you’re going to see progress.”

Paredes has been feeding the homeless in several camps in this area since 2006. A good-looking, deeply religious man, he started visiting the camps because of dreams he had beginning in March 2006.

The first time he had the dream, he said, “It was so vivid — the Lord was telling me I needed to go to the streets and feed the homeless. I ignored it.”

But Paredes, a former Marine who was in Vietnam during the final evacuation of the U.S. armed forces, said the dream visited him again three months later. “I sat up in bed and told my wife, ‘We have to start feeding the homeless,’ ” he said.

But Paredes, a former Marine who was in Vietnam during the final evacuation of the U.S. armed forces, said the dream visited him again three months later. “I sat up in bed and told my wife, ‘We have to start feeding the homeless,’ ” he said.

And so they did. Paredes took on the chore part time at first and then as an almost full-time job after he retired from the U.S. Postal Service in 2009. Early on he met Pastor Maurice Gilmore of Spoken Word Ministries, who has been working with the homeless in Fort Worth on and off for 25 years. The two have been working together for the past several years. Paredes used to supply the needs of several camps, but now he’s down to just two, plus one house where four former homeless campers now live.

During the week, Paredes buys bulk foods and breaks them down into lots that he takes to the camps on Saturdays. At his home in north Fort Worth he proudly shows off his pantry: Racks of shelves in his garage hold five-pound sacks of rice and beans, plus coffee, juice, bottled water, boxes of chips, and condiments. A freezer holds breads and ice; two large fridges are filled with yogurt, cheese, milk, and bags of tortillas.

Those who stay in the organized shelters get three meals a day, “and a lot of churches put on a good spread for the homeless on the weekends,” he said. But it’s not always easy for those who live in the camps to get enough food every day, he said, even though many of the campers make regular trips to the shelters for meals.

Paredes is not part of a church or other charity group. He’s just someone who decided that this was what he was supposed to do. He usually spends $800 to $1,400 a month on the food — and sometimes tents — out of his own pocket.

“My kids are grown, I have my pensions from both the Marines and the post office, so I can afford it,” he said. “Not easily, but it’s worth it to me.”

Initially, coming up with the food was difficult. In his second month he ran short with dozens of people still in line. The third month, he had just enough to get through. Since then, he said, “We’ve never run out. Food comes from a neighbor, a friend, a church.”

Paredes has worked with a lot of churches since he started. But few of them, he said, share his commitment. “I’ve watched 40 churches come and go. They help, and then they quit. It’s just one thing or another,” he said.

The folks who live in the camps do so in part because there are fewer rules there than in the shelters, but Paredes has his own rules and chooses who and how he helps. He wants to help those who are interested in getting out of the camps, finding jobs and housing, and getting back into productive lives.

The folks who live in the camps do so in part because there are fewer rules there than in the shelters, but Paredes has his own rules and chooses who and how he helps. He wants to help those who are interested in getting out of the camps, finding jobs and housing, and getting back into productive lives.

Like Gilmore, he said figuring out who will benefit from that kind of help is difficult.

“Some of these guys love the camps or love the shelter. Why not? You get three squares, there’s plenty of drugs available, a lot of them have government checks coming in every month, and a lot of them get $200 a month in food stamps [from several different states] that they sell for 50 cents on the dollar. Why give that up and go to work?”

When he gets ready to give someone a tent, he tells them he doesn’t want “to see that tent growing roots. This is a temporary shelter until we can get you into a real home.”

He also no longer provides food to any camp that permits drugs or alcohol. “There’s a big percentage of people you can’t help because they don’t want to help themselves,” he said. “And doing drugs is no way to help yourself to get out of this situation.”

Little Wolf’s camp is free of alcohol and drugs, but that doesn’t mean that some of the eight to 10 regular residents don’t utilize them elsewhere. Another of its denizens is Stevie-O, an electrician who admits he can’t keep a job because as soon as he has money in his pocket he wants to drink.

“That’s just who I am,” Stevie-O said. He’s a young man of 30, with tousled hair and a ready smile. He’s been homeless for about 10 years. He’s done jail time for vagrancy and petty theft. At the shelters, he said, “your stuff gets stolen.

“This is the best camp I was ever in,” he beamed. “Everybody is a family. Everybody puts in. That’s only fair.”

To hold up his end Stevie-O panhandles and also collects and sells aluminum cans. But nobody at the camp brings in enough that they don’t need the weekly visits from Paredes and Gilmore. And when Saturday morning arrives, out come the two old grocery store baskets — key components for street living, particularly if you’re collecting cans — to get filled up a couple of times each. It’s the one time of the week that the camp is vulnerable to being spotted.

The de facto leader of the encampment is a blond, fit, well- groomed, articulate man in his mid-40s called Cowboy. He looks like he might have been a surfer in a previous life.

“You know, I could walk out of here and get a job. But this is a life choice, and it’s been my choice of living for about 18 years. Everything we do is a choice,” he said, and laughed. “Unfortunately, I made a few bad ones over the years and wound up doing some federal time and some state time. But now this is home.” He wouldn’t give details of his criminal record.

Why doesn’t he stay in a shelter, where there’s running water and other amenities?

“Oh, man, you’ve got to be kidding,” he said. “My gal Colleen and I have a car and this camp. Why would you want to live in a shelter when you can live out here in the woods with friends?”

Colleen agreed. “Have you ever stayed at the shelters?” she asked. She ended up homeless about a year ago when her job as an ice cream truck driver was axed. “The men are separated from the women, you can’t show affection — I can’t even hold Cowboy’s hand or give him a kiss goodnight. And you have to be in by a certain time, and you can’t leave — and don’t even get me started on the bedbugs and the fleas!”

Colleen agreed. “Have you ever stayed at the shelters?” she asked. She ended up homeless about a year ago when her job as an ice cream truck driver was axed. “The men are separated from the women, you can’t show affection — I can’t even hold Cowboy’s hand or give him a kiss goodnight. And you have to be in by a certain time, and you can’t leave — and don’t even get me started on the bedbugs and the fleas!”

Little Wolf and his pal worked for weeks — “with our hands and feet and a broken shovel” — creating this particular camp, choosing an area unlikely to be seen or stumbled upon by accident.

“If the city knew this camp existed, they’d shut us down or arrest us,” said Brandy, a well-spoken young woman living at the campsite.

Thornton said police and code inspectors enforce relevant ordinances when they find homeless camps, but that there is no specific policy regarding them.

Little Wolf said he’s been on his own since he was 16. “I just chose to do it on my own, without family,” he said. “Because whenever I do stay with my family, I feel like a burden.” He’s working hard on getting a job. It’s taken him eight months, but he finally located his birth certificate and obtained a Social Security card and a state-issued identity card.

“When I get a job, I’ll be good, you know?” he said.

But then he admitted that it’s not all about getting a job — a sentiment that just about everyone at the camp agreed with.

“I’m not ready to get my head out of my butt yet,” Little Wolf said. And like Cowboy, he loves his freedom. “My tent, my rules,” he said.

“I’m not ready to get my head out of my butt yet,” Little Wolf said. And like Cowboy, he loves his freedom. “My tent, my rules,” he said.

Richard, 50, said he stays at the camp because, “It’s crowded in the shelters, they search you going in, you have to be in by 5 p.m., you have to check your beer at the door.”

One of his campmates, Robert, said the camp is peaceful. “There’s just too much drama over there at the shelters,” he said.

But in some camps, there’s plenty of drama — the kind that can get you killed.

At a camp along the river that has since been closed, Paredes said, a man was beaten so badly — by three men wielding baseball bats — that he had to be taken to the hospital. At the former Tent City near Riverside and East Lancaster, Paredes said, two men were stabbed shortly before the camp was shut down.

“But those are the exceptions,” he said. “Most camps are self-policing and function as a family. They protect their camp as a family.”

Even the camps that don’t function so safely, Paredes said, are a better alternative than simply going it alone on the street. For those fending for themselves, outside of the protection of either a shelter or a camp, “There is a lot more violence,” he said, including muggings and rape.

Cowboy and Colleen say they’re committed to their camp family, even though they expect to get back on their feet and out of the camp soon.

“Don’t worry, they’re family,” Colleen said of Little Wolf and Stevie-O. “We’ll take them with us.”

City and charity officials defend the conditions at places like Presbyterian Night Shelter, Salvation Army’s Mabee Center, and the Union Gospel Mission — especially considering that, on most nights, as many as 1,000 of the city’s 2,000 or so homeless people eat and sleep there.

“Our shelters do a great job, given the resources they have, of providing a dignified, safe, and sanitary environment,” said Thornton. “Is there room for improvement? Sure.”

But people like Paredes and other charity workers say the camp dwellers have a point about the shelters.

“I wouldn’t send my worst enemy to the Presbyterian Night Shelter,” said Buckley, of Heaven’s Resources, who stayed at the shelter in January to find out what the conditions were actually like.

Even if the campers don’t want to stay there, the shelters provide them with things they can’t get elsewhere, like hot showers. The only price of admission for those is a scan that shows you’ve taken and passed a tuberculosis test. Nearly all of the shelters require them to prevent outbreaks of the disease.

The city’s strategy for dealing with homelessness is multifaceted and well funded, with $2.8 million allocated to the Directions Home program this year. The program’s goal is to make homelessness “a rare, short-term, and non-recurring experience” by 2018, according to the program’s web site.

“We’re making good progress,” said Thornton. He pointed to a report issued in April showing the city’s program is working well with a number of local agencies toward that goal. To date, more than 1,000 people have enrolled in case management programs, and nearly 500 have obtained housing.

“That’s pretty darn exciting,” he said.

“That’s pretty darn exciting,” he said.

To address the needs of those who won’t stay in the shelters, the city employs an outreach team of professionals who go to different encampments and encourage people to make healthy choices. To Thornton, that means moving people from camps and into shelters so they can get the assistance of caseworkers.

Cindy Crain, executive director of the Tarrant County Homeless Coalition, said the most effective cure for homelessness is to keep people from losing their homes in the first place. In 2009 and 2010, the county used about $7.2 million in federal stimulus funds to prevent 2,931 evictions and find new housing for nearly 500 people who’d recently lost their homes.

Last month the county received another federal injection of almost $1 million through a program called Continuum of Care. A good chunk of that money will go to Catholic Charities to start a new housing program for chronically unsheltered homeless. The charity’s plan is to lease 12 apartments and sublet them to people in its housing program. The rest of the money will go to a Salvation Army veterans program and a homeless information management system.

Crain is convinced that homeless people “will be better in an emergency shelter” than in camps. “They need to get off the street,” she said.

Mike Phipps, a leader of the West Meadowbrook Neighborhood Association, said that getting the homeless off the street and out of the informal camps would help the neighborhoods as well. He’s not so much worried about those who are doing their best to get back to self-sufficiency, he said, as he is about the “professional vagrants” who choose, long-term, to live in camps or squat in vacant buildings. And he’s not seeing as much progress as he’d like in that area.

“They have the right to choose to live nowhere, but [not] if it interferes with my rights or the rights of my neighbors,” he said.

What it comes down to in the end, Buckley said, is that there is no one solution that fits everyone.

There are success stories out of the camps. Robin, for instance, with the help of Paredes and others, has moved with another couple into a house not far from the shelters. She and her husband Lonnie had been homeless and living in camps for four years.

The house is far from perfect — in fact, it doesn’t even have running water or electricity yet, though the owner expects to get those utilities hooked up within a couple of weeks. The house had been boarded up because thieves had stolen copper wiring and plumbing pipe. The owner, a businessman, is allowing the two couples to live there rent-free while they work on cleaning it up. Then he will charge them $400 a month.

In two months, Robin and Lonnie and the other couple, Andrea and Ray, have cleaned the house and painted most of it and were given a load of good quality furniture by Catholic Charities.

In two months, Robin and Lonnie and the other couple, Andrea and Ray, have cleaned the house and painted most of it and were given a load of good quality furniture by Catholic Charities.

Robin’s face glows with excitement at being able to live there, away from the camps and off the streets. “There for a while, we had everything,” Robin said. “But then we lost our jobs and we lost our home … but finally we got out of it.”

And she’s planning to stay out of it. In the fall she will begin a nursing program at Tarrant County College. She proudly shows off her paperwork — her ticket to an education and a new life.

“People tell me, ‘You’re a survivor,’ but anyone who gets out of the homeless situation is a survivor to me,” she said.

To help make ends meet, Ray, tall and lanky, does yard work at more than a dozen neighborhood homes these days, though he’s a chef by trade. “I had physical problems” — he’s a diabetic — “and couldn’t chef anymore. But I love mowing lawns. I really do,” he said.

He’s scheduled soon for a gall bladder operation that he hopes will allow him to go back to work in restaurants without being in constant pain.

Andrea also has big plans — she wants to go to culinary school.

“I want to go into baking, and I want to come up with desserts that a diabetic can eat that really taste great,” she said.

“Peach cobbler,” said Ray. “I’d give anything to have a peach cobbler for my birthday.”

My husband walked out on a job paying him $1000 a week, 5 kids and 18 years of marriage for the freedom of homelessness here in tent city. Where charities will take care of the necessities and he can shoot up as much dope as he wants with no accountability. Personally I think the city and the state should be much harder on these people who choose to abandon all responsibility and leave their lives to be a burden on society.

[…] A Camp Called Home – “We was living in Tent City over on Lancaster and … couple of weeks. The house had been boarded up because thieves had stolen copper wiring and plumbing pipe. The owner, a businessman, is allowing the two couples to live there rent-free while they … Categories general […]

How can I get ahold of Little Wolf? I would like to help him and his friends. I have a van and could possibly give them rides to go pick up the supplies they need to bring back to his camp. That is if his camp still exists… My name Priscilla/ 8179023559

I have to say I have serious respect for this Buckley guy a lot of charities donors or whatever they take the scheduled tour of overnight and day shelters and give the staff there time to paint a facade over it but Buckley actually saw first hand the REAL shelter conditions… I’ve been on the streets now since march of 2015 …in dallas fort worth and for half a year Denver…and I am 27 … I’ve had a lot of run ins with outreach trying to convince me to go to shelters…. no not happening… I prefer to stay by myself and try to do my own thing I dont drink or do drugs I try to keep my campsite hidden… but inevitably a city worker always stumbles onto my camp and makes me move… the last time i had a day to move 6 months of accumulated items food clothing tarps tents etc… and a brand new cot that almost got stolen by one of the city workers he put it in the back of his truck… point is the city for the most part isnt doing anything long term to help the homeless just shuffling them around from place to place and throwing their belongings away

Not all homeless ppl are drug addicts or degenerates yeah theres a few that choose to live this way because it is nice for awhile the freedom the outdoors and while it lasts the peace

I’ve had several jobs before but its difficult to hold a job when you’re constantly worried about your belongings or unable to take a shower or have access to clean clothes

These issues are especially true In these covid times

Just a few thoughts I felt compelled to share

I live in a RV on the streets. Been homeless with 3 dogs for 2.5 months now. I was a waitress. I am filing for disability cause I have carpal tunnel and arthritis in both hands. I also have sciatica. I’m not afraid to work. I’ve had 3 jobs at one time. And I do blame a lot on covid. I was working on my disability and getting my license back in order after a no insurance ticket that suspended my license and another that I could not pay which lead me into a snowball effect. Was getting all that straightened out when covid and it stopped or put a hault on everything. I am now in the process of getting back on track..yet again… but it is hard to do living on the streets in a RV with no electricity or water. My dogs are my babies. Like my children. If you got evicted, would you get rid of your child. My oldest is 14. He has been through a divorce and lots of moving with me. My youngest are 6.5 months old brothers. They have saved my life. And I do mean that. To them, this is an adventure. They don’t know this is not the normal. The animal shelters give me food for them. So they eat better than me most of the time. It is hard leaving them in my RV on the streets while I go try to work. I picked up a side job on the weekends, and want to get a job. But I don’t know where I may be parked next week. Everyday I leave my RV and come back, I have a sigh of relief that there is not a note on my door. Then I come home one day and have an orange sticker on my door that I have to move. So down the street and around the corner we go. How long can I stay at this spot.

I have not filed taxes in a long long time. After my divorce, I did not want to live, so why would I worry about taxes. The last few years, I’ve tried to see what to do. Called a # off the radio to help, but it would cost me $250. I would pay it if I could. But I’m having trouble paying rent and gas for truck so I can do what ever to survive. I barely have money for anything I may need or want. And therefore I never got my stimulus check. And when I try to go online while my hands hurt, I keep running into road blocks. Try to call. And run around with pressing # on phone to get another road block or them telling you to go on-line. I just wish I could get some help getting all this stuff lined back out and getting back on track.

Just typing this has my hand all numb. Sometimes I can’t feel if I’m actually holding something or not.

I just want a spot to put my RV and have electricity and water and live my life with my babies. And I have some work ideas. Just depends where I end up, but just hard to make things happen being in the situation I’m in. I ask… what did I do to deserve this? I don’t feel like I’m a bad person. But I don’t really have anybody. My best friend helps when and how she can. If not for her, I can say without a doubt…. I would not be here. She saved my life and she is all I feel I have. My son is grown and has his life and I have him and my grandmother.