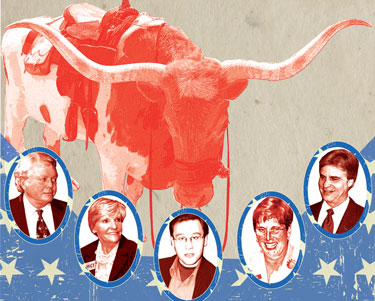

Aw, look at the five mayoral candidates. Aren’t they sweet? The play together so nicely! They vowed a clean, friendly race at their first forum in March, and so far they’ve stuck to the game plan. They even praise one another, saying any of them would make a great replacement for Mike Moncrief, whose decision not to run again has set up the most interesting mayor’s race here in many years.

That doesn’t mean the facade won’t crack eventually — especially since this is one of the most trying periods in Fort Worth’s recent history. Sometimes the poison starts flowing more freely nearer the election date, when candidates begin worrying about polls, and their handlers can’t resist the urge to go for the jugular via emails, ads, and fliers. Recently, Betsy Price questioned Jim Lane’s ability to be objective on police and fire issues after he reported receiving more than $150,000 in campaign contributions from police and fire groups, but that was a polite jab rather than a sucker punch.

A friendly race, perhaps, but not without its dramas. Take Lane’s strong support from the police and firefighter groups — usually a very good thing for a Fort Worth candidate. However, in a year when police and fire retirement benefits have become a key issue in the struggle to fix major problems with the city retirement system, that support might come back to bite him.

Then there’s Price, who has done a solid job as Tarrant County tax assessor and collector for 10 years. A Republican, Price was recruited for the mayor’s race by U.S. Rep. Kay Granger, cheerleader in chief for the controversial Trinity River Vision project. To some, Price is just Mayor Mike Moncrief in a (tasteful) dress. And with the price tag for the TRV continuing to balloon while funding for the huge project becomes more uncertain and local opposition to it more organized, Price’s close ties to Granger could turn out to be a two-edged sword.

Another factor this time around could be the influence of neighborhood groups. Those organizations in the past tended to stay focused on their own hyperlocal concerns, but in recent years they’ve tapped into the internet, embraced social networking, organized, collaborated, and grown more political than ever. The primary catalyst: concerns about urban drilling. And on that issue, critics have noted that Lane’s campaign treasurer is former mayor Ken Barr, who works as a consultant with Chesapeake Energy. Barr laid the groundwork for drilling during his last term as mayor before Moncrief took over in 2003.

At recent neighborhood forums, the crowds seemed to respond most strongly to political independent Cathy Hirt, a former city council member and former president of the Fort Worth League of Neighborhoods, and Dan Barrett, a Democrat who served as a state representative for one term, from 2007 to 2009.

That could mean Hirt, who seems most likely to challenge the status quo at city hall, will split her supporters with Barrett, a longtime Fort Worth resident who’s new to city politics. He proved himself an effective campaigner by getting himself elected to the Texas Legislature as a Democrat in a Republican-heavy district. But in the mayor’s race, some see him only as a spoiler.

Local filmmaker Nicholas Zebrun is by far the youngest candidate at 27, and he’s bright and engaging. But in his first venture into politics, he’s made sporadic public appearances, has reported spending all of $6 on his campaign so far, and is — surprise — considered a very long shot.

Fort Worth voters are nonchalant about local elections, and this one likely won’t be much different, particularly given the happy-happy joy-joy being tossed around during mayor forums.

Cordial politicking tends to lower the turnout, said Allan Saxe, associate professor of political science at University of Texas at Arlington. “It’s a strange irony that we want people to turn out and vote, but we also don’t want mean elections, and that’s what generally turns people out to vote on a race.”

Low turnout also tends to heavily favor incumbents, the status quo, and those with easy name recognition: Even with city hall mired in financial problems, ethical quandaries, and a lack of transparency, Moncrief waltzed to an easy re-election in May 2009, when only about 6 percent of registered voters bothered to cast a ballot. In a city of more than 700,000 residents, only 14,000 voted for Moncrief — and yet he drew 70 percent of the votes cast. His opponents — former city councilman Clyde Picht and East Side activist Louis McBee — drew fewer than 6,000 votes combined.

Collectively the five candidates are expected to spend more than $1 million before it’s all over, making it the most expensive campaign in city history — especially if, as expected, it goes into a runoff. But whoever wins will have little time to celebrate.

“Anybody who goes in there today is going to have a hard row to hoe,” said Bob Bolen, mayor from 1982 to 1991.

After his first election in 2003, Moncrief skipped most debates and forums and sailed through three re-elections without saying much. This season’s mayoral campaign, by comparison, is playing out publicly. Candidates showed their colors early on during the first open forum last month at the Crestwood Neighborhood Association meeting.

About 50 people, most of them from the little neighborhood behind Montgomery Plaza in the West Seventh Street corridor, gathered at a small church to nosh on pizza and soda pop while they listened to the candidates. Before the forum began, several residents mentioned gas drilling as their main concern and said they were leaning in Hirt’s direction but were reserving judgment until after they’d heard everybody’s pitch.

Hirt stands out from all the other candidates in at least one way. She’s the only one who filed for the position before Moncrief announced his decision to vacate office. The other candidates waited, and some, such as Price and Lane, said they wouldn’t have run had Moncrief decided to stay.

“I’m the only one who put myself out there,” Hirt said. “It didn’t make any difference to me. I felt there was a need for better leadership.”

During her years on the city council from 1996 to 1999, Hirt established a reputation as an independent thinker who was willing to move away from the majority. She wasn’t a flamethrower like former council member Chuck Silcox, but she made her opinions known and voted accordingly. She’s tall and direct. Throw in a willingness to buck the status quo, and Hirt wasn’t always popular among the male-dominated bureaucracy and business circles. Even today, she’s still characterized by critics as “another Laura Miller,” a reference to the former Dallas mayor who was considered smart and passionate but difficult to work with. (This may be the first time in Fort Worth history that two women have run simultaneously for the mayor’s job.)

At recent forums, Hirt seemed more reserved than in the past. She said it’s not a conscious image makeover, although she agreed she is deliberate these days. “I’m passionate about running for mayor, just as passionate as anything else I’ve dedicated my life to, but I’m also aware of the fact that a mayor is the political leader of a community,” she said. “You want somebody you can trust, someone who listens, somebody who doesn’t jump to conclusions and is open to all sides. … So I’m in a listening mode more than a talking mode.”

As for the criticism that she can be polarizing, Hirt pointed out that she’s served with dozens of groups and committees over the years and has been nominated to lead many of those organizations. That doesn’t mean she’s biting her tongue. During the Crestwood forum and in subsequent engagements, Hirt made it clear why she’s not the favorite of the downtown business elite or the police and fire associations. Her primary concern is the city’s stressed pension system — a red flag for police and fire groups. And her thoughts on the Trinity River Vision make some people shudder. The TRV is a billion-dollar development expected to create a downtown lake and attract major commercial development while also reducing the potential for flooding. Hirt says the river could be cleaned and made pretty and less flood-prone at a fraction of the proposed cost, and she would prefer more emphasis on parkland.

She isn’t Granger’s favorite to promote the river, she isn’t the choice of police and fire groups to protect their pensions, and she isn’t viewed as all that friendly to the gas industry. That’s the way she likes it. “We have to elect candidates who are free from undue influence,” she said. “I bring that to the table.”

At that initial forum, Hirt set the tone by saying she expected a clean and civil campaign. The other candidates agreed, and so far there’s been little bickering or backstabbing, even when they’ve spoken to Fort Worth Weekly off the record. The candidates say they like and respect one another even if they disagree on how to handle city affairs.

At that initial forum, Hirt set the tone by saying she expected a clean and civil campaign. The other candidates agreed, and so far there’s been little bickering or backstabbing, even when they’ve spoken to Fort Worth Weekly off the record. The candidates say they like and respect one another even if they disagree on how to handle city affairs.

The police and fire associations that back Lane, like the downtown crowd supporting Price, haven’t always played so nice. The Fort Worth Police Officers Association in particular has played hardball while trying to get their favorite candidates elected, and they’ve been successful. All but one of the current council members sailed into office with help from police. The association boasts 1,200 members, donates plenty of money, hires savvy political consultants, sends out fliers, makes phone calls, and turns out voters. It’s a major reason that police and fire enjoy better benefits than general employees.

Three years ago, Lockheed Martin lobbyist Eric Fox was running for city council. He’d nabbed endorsements from Moncrief, Granger, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and other influential backers who thought his Washington connections might benefit the city. But Fox made a mistake. He didn’t court the police. He missed a public safety forum, choosing to attend a fundraiser instead. The police officers’ political action committee distributed a glossy flier shortly before the election, comparing Fox to Washington lobbyist and convicted felon Jack Abramoff. The police association’s pick, W.B. “Zim” Zimmerman, soon found himself sitting on the city council dais, being humbly welcomed by the powerful mayor who had endorsed his opponent.

Another hot topic for Hirt is air-quality issues related to gas drilling. The city’s basic rule so far has been “drill, baby, drill” — and pass regulations later if it turns out that emissions make people sick. Hirt prefers a more cautious approach, which worries drilling advocates.

Considering all the money it has to throw around, the drilling industry is a huge player in all kinds of politics these days. Besides the income it represents to governments, residents, and local charities, the industry is also one of the biggest downtown tenants. Chesapeake Energy bought the Pier 1 corporate headquarters in 2008 for more than $100 million, and other natural gas companies have followed.

With Moncrief and his council majority as their protectors, drillers have enjoyed generous policies and soft ordinances for 10 years. City officials have mostly looked the other way as a growing number of people called for tougher laws and more enforcement on air, ground, and water pollution. Hirt and Barrett have been the most willing to take a stand on that issue.

Most downtown movers and shakers, along with a large number of influential Tarrant County figures such as County Judge Glen Whitley and Sheriff Dee Anderson, are backing Price. But Hirt has gained the support of many small business owners and professionals, including some who work downtown. Add that to the neighborhood support and Hirt believes she has a solid chance to win the election.

She figures on getting the votes of many of the 6,000 residents who cast their ballots last time for Picht or McBee and predicts that some of those who voted for Moncrief then will be unwilling to vote for a conservative Republican such as Price. Voters who didn’t go to the polls last time might show up on May 14 because of the issues and the lack of an incumbent, she said.

Hirt is so convinced that people are ready for change that she predicted Moncrief would have lost if he had run for re-election. “People are hungry for something different,” she said. “The big thing I get from people is, ‘Promise us you’ll listen to us.’ It breaks your heart.”

Lane’s public image during this campaign is consistent with how he’s handled himself for 20 years in public office — he’s well-spoken, funny, and restrained, his Texas charm accented by Resistol hats and cowboy boots worn with business suits. A laid-back persona doesn’t mean he’s not passionate. Get him riled about something close to his heart, and he’ll get fiery and red-faced in a hurry.

None of the candidates can match Lane’s level of municipal experience, and, not surprisingly, he’s touting that experience as crucial to leading a city of almost 1 million residents through difficult times. Lane can count 12 years as a council member and five years on the Tarrant Regional Water District board along with numerous appointments to various committees and other boards. He knows how to campaign and win elections and how to navigate political waters.

“I’ve got a lot of experience that’s pretty valuable,” he said. “Taking on something like the mayor’s job, you really need to know what you’re getting yourself into. You’ve got eight people who are all elected from their districts, all with their own thoughts and ideas and promises, all strong personalities. The mayor has to be somebody who can build a coalition, because without that coalition of five, you can’t set any policy and you can’t move forward.”

Critics say the mayor’s position is a full-time job these days and predict Lane will be distracted by the law practice that supports his family, including a 4-year-old son. Lane says it’s a non-issue, especially since the council is charged only with setting policies, while the city manager carries out policies and oversees staff. “I’ll devote all the time that’s necessary, but I don’t need to be down there looking over everybody’s shoulder,” he said.

More common, however, are concerns about whether Lane will be distracted by that $150,000 that police and fire groups have poured into his campaign. Both groups are preparing for contract renegotiations — the firefighters’ contract with the city is up in 2013, and the police contract ends in 2012.

More common, however, are concerns about whether Lane will be distracted by that $150,000 that police and fire groups have poured into his campaign. Both groups are preparing for contract renegotiations — the firefighters’ contract with the city is up in 2013, and the police contract ends in 2012.

Price thinks those donations would color Lane’s decisions during contract negotiations.

“It’s significant when about 66 percent of any one candidate’s donations comes from two organizations,” she said. “I don’t see how you can take those types of dollars and separate yourself from them. They’re also working for him, putting up his signs. He has close ties to them.”

At a recent forum, Lane said he’s told his public-safety supporters that, at the bargaining table, if they want to keep their current level of benefits, “they’ll have to pay for them.” He said both groups have told him they’re willing to contribute more from their paychecks for that purpose.

“Everything is negotiable,” he said.

Bolen considers the stressed pension system as the city’s biggest threat and the major campaign issue. He’s not slinging arrows at police and fire groups. He has children serving on the police force and realizes the importance of public safety in a big city. But it’s time to come up with new solutions, he said. Standing up to those powerful groups can be tough politically, more so if a candidate is “embedded” with them, he said.

“They can’t keep getting what they’re getting today, because there is no money,” he said. “You can’t pay in for 25 years and then retire for 35 years at almost full pay. That problem has got to be solved, and whoever convinces me they can do it, that’s the way I’m going to go.”

Lane believes the fund is more stable than people realize and can be strengthened by measures such as controlling overtime, a major contributor to pension payments and the system’s problems.

“I’m not for sure anybody knows exactly what they’re talking about on this,” he said. “This thing has gotten way out of proportion, and I don’t think people really understand it all.”

Lane called the Weekly after announcing his candidacy and vowed to return reporters’ phone calls, respond to questions, and insist on transparency at city hall. He didn’t need to call. He’s always been open and available to reporters. But he realized that transparency was a problem under Moncrief, whose reticence in speaking with the news media — he blackballed the Weekly for eight years — set a tone at city hall that has filtered down to all levels. Getting basic information, even after submitting official records requests, has been difficult in recent years. All of the current candidates vow to change that.

As a council member, Lane enjoyed plenty of neighborhood support, particularly in heavily Hispanic and African-American areas. That hasn’t changed. And he is drawing support from local business leaders. But his decision to appoint Barr as his campaign treasurer worries some. Lane points out that he’s received no financial support from Chesapeake Energy, Barr’s employer, and that, as his longtime friend and fraternity brother, Barr was a natural choice.

To prove his independence from the gas industry, Lane mentioned being sued by a gas company after he resisted having a pipeline laid across his ranch property in Parker County not long ago. The suit was later dropped. During forums he’s talked about holding the industry accountable if air studies that are currently being evaluated reveal significant amounts of pollution.

“He recognizes the economic benefits that the Barnett Shale has brought to Fort Worth, but he is committed to seeing that we have rules and regulations in place that protect our neighborhoods,” Barr said. “We have to protect neighborhoods, but part of protecting our community is having jobs and a strong economy.”

The next city council may have to deal with expanding the council from eight to 10 single-member districts (plus the mayor) — a highly contentious process. Lane was on the city council during the last redistricting, after the 2000 census. That experience is priceless for leading a council through the next round.

County politics are notoriously rough and tumble, and few elected officials enjoy widespread popularity. Most are loved and hated equally. Price, though, has won a lot of support among county employees without developing an equal number of critics. Not bad for someone who took over a troubled and anachronistic tax collection office and brought it into the 21st century by vastly improving efficiency without adding overhead.

“We have had a 50 percent increase in our workload — you know how much Tarrant County has grown — and less than a 5 percent increase in the budget in 10 years,” she said.

On her first day at the county tax office in 2001, she looked in a vault and saw stacks of checks — about $300 million worth — from floor to ceiling. They’d been sitting unprocessed for weeks. She took over a staff with low morale, revved them up, processed the checks, embraced technology, and streamlined the system of collecting and processing county taxes. The office went on to win several national awards for efficiency.

“Nowadays, you send me a check, you don’t get any float — it goes in the bank the same day or at the very least the next morning,” she said.

The move from county tax collector to mayor is a rare one. Politically ambitious tax collectors are more likely to become county commissioners, judges, or state legislators. “Moving from full-time county to a full-time job at the city is a change of pay, certainly,” she said, laughing. (The county tax assessor’s job pays about $130,000 plus a car. The mayor’s job pays $29,000.)

However, Price and her husband have done well financially over the years. These days her motivation is public service, she said. Besides Granger, state representatives Charlie Geren and Barbara Nash and former Texas Speaker of the House Gib Lewis have endorsed her.

However, Price and her husband have done well financially over the years. These days her motivation is public service, she said. Besides Granger, state representatives Charlie Geren and Barbara Nash and former Texas Speaker of the House Gib Lewis have endorsed her.

She was content with her county job — and why not? Still, she couldn’t refuse Granger, the congresswoman who has been touting the TRV for years and securing federal earmarks for it in Washington.

“I’ve never been looking to run for mayor,” Price said. “I’m not in this for the politics. It’s about service for the citizens. Kay Granger came to me in early November, and several other businessmen and some of our friends followed, and they said, ‘You need to run for mayor.’ ”

It didn’t hurt that Price is a former chairwoman of Streams & Valleys Inc., a nonprofit that helped get the ball rolling on the TRV and is committed to “saving, sharing, and celebrating the Trinity River in Fort Worth,” according to its web site.

Price’s inexperience in city affairs is revealed sometimes during forums with articulate and veteran city players Lane and Hirt. Price’s frequent references to her county work to illustrate how she’d do things at city hall is a turnoff to some voters. On the other hand, not having served in city politics means she doesn’t have past votes on city issues coming back to haunt her.

“Jim Lane and Cathy Hirt both served on the council at the time when the budget issues … and the pension issues were forefront, and they weren’t addressed,” she said. “Even if the national recession hadn’t occurred, we were still going to have budget shortfalls because the city’s been spending more than they were taking in.”

Price insists she’ll approach Trinity River development with the same bottom-line efficiency she used in the tax office. When times are flush, risky investments are more acceptable, she said, but when the economy falters, projects have to be done in smaller increments. Still, she makes no bones about supporting the project that she expects to grow the city’s tax base for decades to come.

Her fiscal conservatism rears its head even higher when discussing the pension fund. “This is about protecting the taxpayers,” she said. “We have to get the city’s budget in shape.”

The police and fire groups haven’t donated to her campaign, based on recently filed campaign contribution reports.

She also talks tough on gas drilling. No one’s more aware than she is of the boom’s economic benefits. When she became tax collector 10 years ago, her office billed and collected 500,000 property tax accounts, including 8,000 mineral accounts. That amount has grown to nearly 900,000 property tax accounts, including about 200,000 mineral accounts. But public safety comes first, she said.

“I’m not in this unfettered ‘drill baby, drill’ camp,” she said. “First and foremost it’s got to be safe. We have to have safe neighborhoods, safe schools, clean air, clean water. We’ve kind of had a hodgepodge of rules. It’s time to go back and look at the rules.”

The Fort Worth League of Neighborhoods packed a large room at the Botanic Gardens last week with all five mayoral candidates and a couple of hundred people who came to question and listen. Emcee Libby Willis encouraged the crowd to hold the applause until the end of the forum. But twice the crowd erupted in spontaneous applause — once for Hirt and once for Barrett, the two candidates who appear most likely to challenge business-as-usual at city hall.

Barrett’s 30-days-out campaign finance reports shows only $20,000 in contributions, far less than Hirt’s $140,000, Price’s $183,000, or Lane’s $227,000. Barrett isn’t fazed. He’s certain he’ll win enough votes to make it to a runoff.

“Once I get in that runoff I can win,” he said. “If I didn’t believe that, I wouldn’t be running.”

His theory: He pulled off an unexpected win to get to the legislature and figures he can work the same magic in his hometown. After State Rep. Anna Mowery resigned in 2007, a special election was held to fill her District 97 seat. The district was solidly Republican, but Barrett campaigned tirelessly and pulled off a surprise victory. His term was short-lived: He ran for re-election the next year and was beaten. But he got 24,000 votes, and that gives him hope.

“If I can turn out just the people who voted for me in the city of Fort Worth in my loss in 2008, I could win without a runoff,” he said.

He mentions his legislative experience frequently in the forums, but his critics snicker. Because Barrett won a special election after the 2007 session and was voted out before the 2009 session, he never actually authored or sponsored a legislative bill or even voted on one. Barrett says the criticism is unfounded because he did plenty of work during that interim, serving on committees, attending hearings, and “form[ing] a lot of relationships and contacts” that will help him be an effective ambassador for Fort Worth in the legislative process.

Barrett’s campaign manager, Travis Parmer, also expressed confidence in victory, although he didn’t mention anything about drawing enough votes to win the election outright on May 14.

“This race is about getting to the runoff,” he said. “The key is to be one of the top two vote-getters. You win in June by getting to the runoff in May.”

Much of the support is expected to come from neighborhoods.

“We’re counting on regular folks,” Parmer said. “City hall has lost touch with average folks.”

After the Botanic Gardens forum, I asked Willis which candidate seemed to be drawing the most support from neighborhoods. She wouldn’t be pinned down. Neighborhoods are diverse, and all of the candidates are feeling the love, she said. So I asked her what traits the neighborhood groups are most looking for in the next mayor.

Her response revealed the shortcomings of the current mayor’s tight-lipped administration and the hopes that residents are holding out for his replacement.

“We have an opportunity for new leadership, and it’s time for the city to be listening to neighborhoods more than it has been in the last eight to 10 years,” she said.

All the candidates impress Bolen. He said he doesn’t recall an election when so many excellent candidates were vying for the mayor’s job. He’s watching and listening and said he’ll vote for the person who offers the best solutions, not the best sound bites. So far, he’s leaning toward Price based on her record of fiscal efficiency at the tax office, but he lauded Lane’s experience and background and acknowledged Hirt’s popularity in the neighborhoods.

Most of all, he said, whoever wins must do what’s right and “quit worrying about getting re-elected — and that’s difficult to do.”