Two years before Billy Bob’s Texas became reality, its namesake, Billy Bob Barnett, invited Stockyards fixture Steve Murrin on a tour of the old building he planned to transform into a massive honkytonk. Murrin’s 9-year-old son Philip tagged along, riding his bicycle around on the concrete floor while Barnett explained his vision.

Barnett pointed to an area where he planned to build an indoor rodeo arena. Philip rode over to that spot, imagining bulls bucking there one day.

After the club opened, Philip went with his dad to see Willie Nelson perform that first week. Barnett took Philip out to Nelson’s bus to meet the singer just before showtime.

After the club opened, Philip went with his dad to see Willie Nelson perform that first week. Barnett took Philip out to Nelson’s bus to meet the singer just before showtime.

“It’s time to go play,” Nelson announced and grabbed the kid by the hand.

“Willie took me onstage and put me underneath [sister Bobbie Nelson’s] piano and said, ‘Sit under there,’ and I sat there for the whole show,” Philip said. “It was a complete sea of people and an incredible amount of energy emitting from the stage and the crowd. It was really cool.”

The thousands of people who attended the grand opening were no less wide-eyed. Billy Bob’s Texas burst through the gate on April 1, 1981, like a rank bull, slobbering, snorting, and kicking up dust as the world’s largest honkytonk. The concept was as brash as its owners and operators. Barnett, Spencer Taylor, Hub Baker, and assorted good ol’ boys with penchants for hard living and big dreams introduced the club to an audience infatuated by Outlaw music and Urban Cowboy.

“It was pure chaos,” said sports radio personality Greg “Greggo” Williams, a young bartender back then. “When I write my book one of these days, that’s going to be a chapter. It was a wild time during some wild times.”

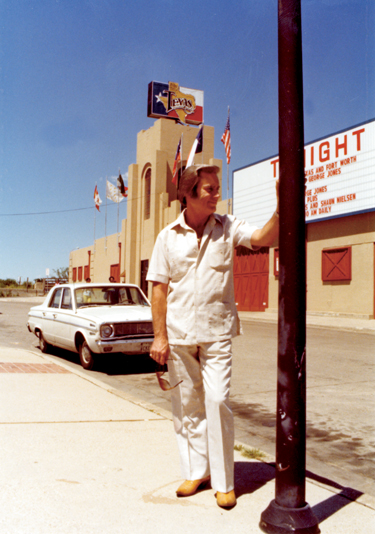

Barnett grew up on a ranch, played in the National Football League, built bars and restaurants, and became Fort Worth’s distributor for Miller Beer in the 1970s. He sold that lucrative distributorship to finance Billy Bob’s, a club inspired in part by the release of Urban Cowboy, with its action centering on Gilley’s Club near Houston. Barnett loved Western culture, appreciated the historical context of the Stockyards, and envisioned a bigger, better version of Gilley’s plopped smack-dab in cowboy central.

In the decades since then, country music’s biggest stars have performed there. Movie and TV directors filmed scenes there. Tourists became infatuated. But after a few years the urban cowboy trend fizzled out like a spent rodeo bull, broken and tamed. Billy Bob’s went through a bankruptcy and reorganization but evolved into an efficient, family-friendly honkytonk that’s part museum, part amusement park, and part mall, all centered on Western-themed entertainment. That concept has carried it through shifting trends and economic ups and downs, and it remains the most visible attraction in a Stockyards district that ranks among the top tourist spots in the state each year.

In the decades since then, country music’s biggest stars have performed there. Movie and TV directors filmed scenes there. Tourists became infatuated. But after a few years the urban cowboy trend fizzled out like a spent rodeo bull, broken and tamed. Billy Bob’s went through a bankruptcy and reorganization but evolved into an efficient, family-friendly honkytonk that’s part museum, part amusement park, and part mall, all centered on Western-themed entertainment. That concept has carried it through shifting trends and economic ups and downs, and it remains the most visible attraction in a Stockyards district that ranks among the top tourist spots in the state each year.

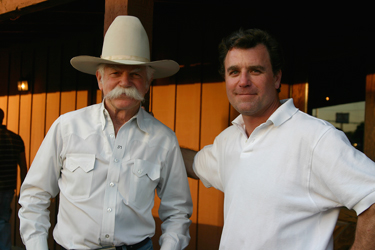

Original characters such as Barnett and Taylor moved on. New blood arrived, led by Stockyards investors Holt Hickman, Don Jury, and Steve Murrin, although the most crucial player turned out to be a former rodeo cowboy turned club manager, Billy Minick. He improved the club’s Western flavor and groomed the brand even as he reined in the rowdiness. A solid number of local regulars keep the cash registers ringing during the week.

Barnett, still an active commercial developer, looks back on his namesake honkytonk like a doting father as it prepares to celebrate its 30th anniversary on Friday. “I’m very proud of what we did when we started it, and what the management has done since then,” he said.

The owners are grayer — they all top 70 years — but a new generation is stepping forward. Minick is handing over the president’s job to his 40-year-old son Concho and moving on to other Stockyards projects. Hickman, Jury, and Murrin all have children who are learning the ropes. They’ll be counted on in the future to help Concho Minick herd the dream farther down the trail.

The owners are grayer — they all top 70 years — but a new generation is stepping forward. Minick is handing over the president’s job to his 40-year-old son Concho and moving on to other Stockyards projects. Hickman, Jury, and Murrin all have children who are learning the ropes. They’ll be counted on in the future to help Concho Minick herd the dream farther down the trail.

“You talk about the last 30 years, we need to talk about the next 30 years,” Murrin said. “We’ve got some fresh runners. It’s going to be a smooth transition.”

It’ll surely be smoother than the grand opening.

That first night was a honkytonk yin and yang — happy people, pissed-off people, good music, a booing crowd, huge profits, lost opportunities.

Stockyards developer and raconteur Murrin sold a river of beer to Billy Bob’s Texas customers during the weeklong grand opening — and he didn’t even work there. He ran the Cowtown Coliseum next door and set up a concession stand to sell suds to the hundreds of people standing in line to get into the huge club. Lines snaked from Billy Bob’s front door, up what is now Rodeo Plaza, past the coliseum, and along East Exchange Avenue.

“We had some of our best nights selling beer to the people standing in line to get into Billy Bob’s,” Murrin said.

The people in line were thirsty. And angry. For weeks prior to the club’s opening, Barnett had been peddling VIP passes by the bushel for $300 each, guaranteeing a private entrance, no lines to wait in, exclusive lounge access, and other perks. The money-raising scheme created a problem that first week.

“You had more people holding VIP memberships than regular patrons, and they’d been promised all these privileges, and they were all pissed off about it,” Williams said. “And you had the fire marshal there who did a headcount and said, OK, nobody else gets in — and you still had a thousand people out there in line holding VIP memberships.”

Williams had helped prepare Billy Bob’s for the grand opening, but work was still being done on the last day. Crews were frantically laying carpet inside even as patrons lined up outside.

“Opening night was the most chaos I’d ever seen in a nightclub,” he said. “There were 50 different bars and 50 different bartenders and 100 waitresses who had never worked together.”

The demand to get inside and be a part of the scene was palpable. Nelson, Waylon Jennings, David Allan Coe, and their brand of Outlaw music were peaking in popularity in 1981. Urban Cowboy was a major hit for John Travolta, cementing country music in the national consciousness much as Saturday Night Fever did for disco in 1977. The club theoretically held 6,000 people, but the first artist to perform recalls looking out at double that number.

“They were stacked in there like cordwood — we estimated 12,000,” said Larry Gatlin of the Gatlin Brothers.

“They were stacked in there like cordwood — we estimated 12,000,” said Larry Gatlin of the Gatlin Brothers.

Nelson was Outlaw No. 1 and the logical first headliner, but he wasn’t available until later in the week. The Gatlin Brothers were riding their hit song “All the Gold in California,” but their show was designed more for listening than dancing. So Gatlin appreciated the club’s design: long tables in front of the stage, with the dance floor behind them — ass-backwards compared to most dancehalls.

But the crowd was there to party.

“You got this big giant dance floor, and it’s at the height of Urban Cowboy and the country-and-western nightclub scene, and Larry Gatlin didn’t want anybody to dance,” Williams said. “He stopped in the middle of a song and said ‘Don’t let my singing interrupt your dancing.’ Everybody booed him. Billy Bob had had a few Jack Daniels by then, and he was going to go do something to Larry Gatlin, but he never did. It was a funny scene and just added to the chaos.”

Gatlin’s memory isn’t much different. He recalled chastising a guy who whistled out during “The Heart,” one of his most earnest songs. “We liked people to be quiet when we sang,” he said.

After the show, Gatlin got a backstage pep talk from former University of Texas football coach Darrell Royal. “He said, ‘Larry Wayne, that ol’ boy was just letting you know he liked you,’ ” Gatlin recalled. “I learned from that. We were singing at the world’s largest beer joint, and they were just being happy and festive. The next time I did it, we tailored the show more toward that. We loved the joint, and we realized we couldn’t do it exactly our way.”

Gatlin was also enamored of Barnett. The burly Aggie stood about 6-foot-5, wore cowboy boots and hats, dreamed big, talked big, lived big, and had deep pockets. That personality marked every inch of his honkytonk.

Gatlin was also enamored of Barnett. The burly Aggie stood about 6-foot-5, wore cowboy boots and hats, dreamed big, talked big, lived big, and had deep pockets. That personality marked every inch of his honkytonk.

“Billy Bob is a great guy, very colorful,” Gatlin said.

The club owner liked to drink. Gatlin joined in the revelry on opening night and eventually found himself straddling a four-legged beast. Mechanical bulls at nightclubs were all the rage in 1981. But at Billy Bob’s, the motto was “real balls, not steel balls.” Barnett insisted on live bulls.

“I was on the bull for about two seconds, and I pushed myself off the backside of it,” Gatlin said. “We’d had so many red beers I don’t think we knew what we were doing.”

The famous mechanical bull ridden so seductively by Debra Winger in Urban Cowboy was at Gilley’s Club, a big metal building in Pasadena that featured live country music, booze, brawling, dancing, and loving. Barnett pumped that prototype full of steroids — his 127,000 square feet of space dwarfed Gilley’s.

“I thought the biggest one-upmanship was that they had real bulls,” said music writer, radio personality, and Fort Worth native Joe Nick Patoski, who covered the Outlaw movement in the 1970s and went on to write books about musicians Willie Nelson, Selena, and Stevie Ray Vaughan.

“When Urban Cowboy came out, every place from here to Maine had mechanical bulls, and everybody had a Charlie Daniels hat, and country music went to shit,” Patoski said. “One of the few good things to occur from that is Billy Bob’s — and it’s still going.”

Opening night with the Gatlin Brothers fell on a Wednesday, and equally huge crowds turned out on Thursday and Friday for shows by Waylon Jennings and on Saturday for a package show featuring John Conlee and Janie Fricke. But the coup de grace was shows by Nelson on Sunday and Monday — not your usual heavy-hitter nights in the honkytonk bidness.

Opening night with the Gatlin Brothers fell on a Wednesday, and equally huge crowds turned out on Thursday and Friday for shows by Waylon Jennings and on Saturday for a package show featuring John Conlee and Janie Fricke. But the coup de grace was shows by Nelson on Sunday and Monday — not your usual heavy-hitter nights in the honkytonk bidness.

Barnett wanted Nelson’s name on the marquee during the grand opening. He and friends had flown to Las Vegas four months earlier to meet with Nelson and personally invite him to perform. No problem, Nelson said.

“We got all excited because Willie said he’d play the opener,” Barnett recalled. Indeed, he was so excited that he forgot to ask how much it was going to cost.

When did he realize his error? “When the contract showed up,” Barnett said.

The price tag staggered him. After negotiating, a deal was settled at $35,000.

“Willie is a great guy, and he was fair,” Barnett said.

One of the fans waiting in line to see Nelson perform was a young Tommy Alverson. In time he would become a regional Texas Music staple and perform on the same stage as Nelson. But in 1981 he was attending the show with a date and two other couples. “We got inside and got our seats, and I went and bought a six pack of beer and brought it back to the table. It was $9, and I thought that was the most ridiculous price for six beers I’d ever heard in my life.”

Several years later, Patoski made his first visit to the honkytonk, for a Delbert McClinton concert. The club’s quality impressed him. “Billy Bob’s is a pleasant place and not a shithole like Gilley’s was,” he said.

But he was underwhelmed by the mall-like ambiance. “There is not exactly soul in the ceiling,” he said.

Sound quality can also be a problem. Making live music sound crisp and clear in what amounts to an airplane hangar isn’t easy. Reserved seats are cheaper than at most concert venues such as Bass Hall or Verizon Theater, and the sound is fine at the front tables. But in general admission areas, it’s hit or miss. I went to see Robert Earl Keen during his heyday 10 years ago, paid general admission, and found myself amid huge crowds packed on either side of the stage. Feeling claustrophobic, I moved farther back. The sound was mushy with echoes. I ended up sitting on a stool at an auxiliary bar, watching the concert on a small TV with tinny speakers and vowing I’d never come to another concert there without reserved seats.

Sound quality can also be a problem. Making live music sound crisp and clear in what amounts to an airplane hangar isn’t easy. Reserved seats are cheaper than at most concert venues such as Bass Hall or Verizon Theater, and the sound is fine at the front tables. But in general admission areas, it’s hit or miss. I went to see Robert Earl Keen during his heyday 10 years ago, paid general admission, and found myself amid huge crowds packed on either side of the stage. Feeling claustrophobic, I moved farther back. The sound was mushy with echoes. I ended up sitting on a stool at an auxiliary bar, watching the concert on a small TV with tinny speakers and vowing I’d never come to another concert there without reserved seats.

On stage, however, the sound is stellar. Billy Bob’s has always embraced rock bands as well as country acts. ZZ Top, Rare Earth, and other rockers were hired that first year. Musicians must hear themselves to play well, and they rely on the club’s crew. “They have the best sound people in the world,” said drummer “Rocking” Ron Thompson, who has played Billy Bob’s countless times since 1981, including for a live album by Doug Stone in 2008.

Some visitors couldn’t care less about the sound. They prefer cheap general admission prices because they’re interested in the bulls, bars, food, shops, pool tables, dance floor, and music memorabilia rather than sitting and watching a concert.

“The key to this place has always been the ticket prices,” entertainment director Robert Gallagher said. “It’s a cheap ticket for reserve and even cheaper for general admission where they can lean on the rail and get a good view for a third of the price.”

Bands keep returning because Gallagher, who’s been there more than 20 years, and his staffers go out of their way to make them feel special. Fort Worth-based Josh Weathers & the True+Endeavors performed there March 18. They’re low on the food chain compared to artists like Nelson, but Billy Bob’s doesn’t discriminate.

Bands keep returning because Gallagher, who’s been there more than 20 years, and his staffers go out of their way to make them feel special. Fort Worth-based Josh Weathers & the True+Endeavors performed there March 18. They’re low on the food chain compared to artists like Nelson, but Billy Bob’s doesn’t discriminate.

“You ask for two bottles of water, you get three. The staff is right there for you,” True+Endeavors saxophonist Bryan Batson said.

That includes a proactive and trained security staff, something not always in place in the early days. “A bar fight broke out between two brothers, and the staff had them in chokeholds in no time and zip-tied them on the floor,” Batson said. “You feel safe knowing they’re there on top of things.”

Even during its wilder early days, Billy Bob’s felt safe compared to honkytonks such as Gilley’s. Asleep at the Wheel frontman Ray Benson saw someone slice a man’s face with a straight razor at Gilley’s in 1980. And he said musicians had difficulty getting paid there.

“That’s another good thing about Billy Bob’s — they don’t screw you over,” he said. “Billy Bob’s is not a rough place by any means.”

Savvy marketing meant that Fort Worth visitors, no matter how important they were, felt they just had to visit the club, former WBAP disc jockey and current SiriusXM Radio host Bill Mack said.

“There was something about the atmosphere,” he said. “It was looked upon as a beer joint, but really and truly it was a cross between a honkytonk and Carnegie Hall.”

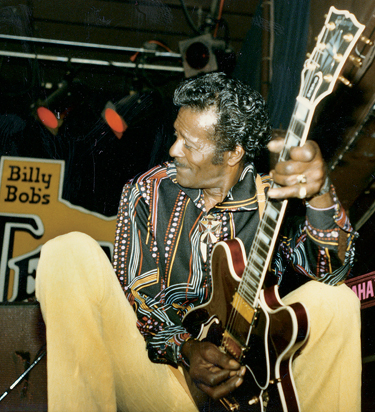

Rock legend Chuck Berry, featured on this week’s cover, played in 1981 to a packed house, and afterward he milled among the late-night (that is, intoxicated) crowd. Club managers scurried to get a protector for the notoriously confrontational musician. “He just shooed away any kind of help or security or bodyguards,” Williams said. “You could tell he cut his teeth in tough places. That wasn’t a tough room to him at all.”

Artists who have played there include some of the best in the rock and country fields, so fledgling artists dream of getting up on that stage. “It’s a quality filter — when people find out you’re playing at Billy Bob’s, they know you don’t suck,” Batson said

Billy Minick hired unknowns and little-knowns along with top acts, and when those unknowns became famous, they remembered the favor. Miranda Lambert recently returned to perform at Billy Bob’s. She could have booked a more lucrative local concert venue after her big score at the 2010 Grammy awards. Instead she sold out back-to-back shows at the honkytonk. “I saw all my heroes play there, and so to return and get to play at Billy Bob’s is such a great feeling every time,” she said.

Gallagher keeps the artists happy, whether that means getting their dirty clothes washed, going shopping, accompanying golf enthusiasts such as Randy Rogers and Wade Bowen to local links, or carousing with thirsty artists after a show. When Lambert’s road crew arrived on a recent Thursday to prepare for her weekend gig, he escorted them to various Stockyards bars, as well as Lola’s Sixth and Spencer’s Corner.

“That’s not work, it’s just starting a three-day weekend together,” he said.

Live bulls were marketing genius, but they almost led to disaster. After building the indoor rodeo arena, Barnett wondered if the pens were tall enough. They were built to standard measurement, but at the last minute Barnett extended the fence another two feet in height to be extra safe. Sure enough, during that first week, “a bull tried to jump the fence and landed right on his middle, leaned one way, and then fell back into the arena, thank God,” he said. “If we hadn’t added the two feet, he would have cleared it like a high-jumper.”

News media camped out the entire week to capture the madness. That kind of attention was something the Stockyards hadn’t seen in a while. Billy Bob’s wasn’t exactly nestled amid niceness. The Stockyards was a stinking collection of barns, cattle pens, cutthroat beer joints, prostitutes, decaying buildings, and crime. Barnett’s plan was to make people overlook it all.

News media camped out the entire week to capture the madness. That kind of attention was something the Stockyards hadn’t seen in a while. Billy Bob’s wasn’t exactly nestled amid niceness. The Stockyards was a stinking collection of barns, cattle pens, cutthroat beer joints, prostitutes, decaying buildings, and crime. Barnett’s plan was to make people overlook it all.

It worked.

“That was the problem with the Stockyards: Nobody believed we could get people to come out to the area because it was blighted, and the reputation was of it being rundown,” Barnett said.

Barnett’s boyhood friend Hub Baker had put up $20,000 to become a partner on the retail sales inside the club, hawking t-shirts and caps. Barnett’s daddy had worked as ranch foreman for Baker’s daddy years earlier, and the boys had grown up together and become friends. “We grossed enough money the first night that I got all my money back,” Baker said. “It was a hell of a deal. The net monthly income was tremendous.”

Heavy rains on Night Two flooded the building and knocked out the power for about 10 minutes with thousands of customers inside. “I thought we were running the Titanic,” Barnett said. “We had to re-break the breakers while standing in water. It got a little dangerous.”

Barnett booked a Who’s Who of performers during the first 90 days to make sure customers kept coming. The owner’s outsized personality could be tough to handle, but few questioned his ability to make things happen. “He was a brilliant businessman — not very popular with vendors or employees or partners or anybody else, but to have that wacky idea at that time and at that location, he was a visionary,” Williams said.

The visions got bigger. Barnett decided to snatch up more Stockyards properties and turn the entire area into a collaborative of nightclubs, shops, and restaurants with a Western theme.

The visions got bigger. Barnett decided to snatch up more Stockyards properties and turn the entire area into a collaborative of nightclubs, shops, and restaurants with a Western theme.

The move would eventually be his undoing. Murrin, who had owned property in the Stockyards for 10 years, had similar visions. He was even more gung ho about keeping everything cowboy.

Philip Murrin, now 41, recalls his dad’s arrival once to pick him up from summer camp. Steve Murrin was sporting a pair of mirrored sunglasses to hide a huge shiner. The night before, the elder Murrin had objected to Barnett’s idea of tearing down some cattle pens to build a horse track.

“I hit him with a chair, and he backhanded me across the VIP room,” Murrin said. “Those early years we had some philosophical differences. We were pals, but that was just one of those 4 a.m. discussions.”

Barnett bought so much surrounding property that the mid-1980s real estate bust hit him hard. He filed for bankruptcy, allowing Murrin to line up new investors and take over the club.

Murrin, glib as ever during the grand reopening in 1989, didn’t hesitate when a Reuters reporter asked him to define a honkytonk. “It’s a place where you expect a little beer, a little music, and maybe a stabbing or shooting once in a while,” he said.

But Billy Bob’s was changing. “Billy Minick really put the right spin on it,” said Asleep at the Wheel’s Benson. “Not that the old one wasn’t good, but they had to change with the times.”

Barnett credits Minick with stabilizing the club’s future. “Billy Minick watched the costs, and he kept the authenticity,” he said. “If anything, Billy Bob’s has become more authentic over the years.”

And family-friendly. The new owners downplayed the carousing. Security inside the club and in the vast parking areas was boosted. Fights weren’t tolerated. Even the rambunctious Murrin settled down and saw the benefit in making the club — and the Stockyards as a whole — more safe and friendly with a Texas charm.

The children of the owners support that philosophy. “It’s very important for us to keep Billy Bob’s true to itself, but we also want to improve on it and to expand,” Philip Murrin said last week.

Concho Minick is the trail boss now, and he and Philip are longtime friends and neighbors. They’ve discussed improving the concert layout and opening other Billy Bob’s Texas clubs in other cities and even overseas. It’s the standard entrepreneurial mantra: If something isn’t growing, it’s dying.

Billy Bob’s isn’t dying. It’s not even sick. Even when Barnett was going bust, his club was surviving financially, he said. Things have continuously improved, and, from where Barnett sits, it looks like it’s on its way to another 30 years.

“Fort Worth is very lucky to have that group of people that care that much about the Stockyards,” he said.