The gently rolling ranchland around Stephenville provides a natural backdrop for Tarleton State University and its emphasis on agricultural studies. But it’s more than a cow college. Its graduates have found success in careers as varied as music (Ryan Bingham), acting (George Kennedy), and politics (Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief).

Another former Tarleton student, Marvin Zindler, made his place in the world as an investigative TV journalist. His reports in the 1970s helped close down the infamous Chicken Ranch, a La Grange brothel. The incident provided the basis for the Broadway play and Hollywood movie The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas.

Another former Tarleton student, Marvin Zindler, made his place in the world as an investigative TV journalist. His reports in the 1970s helped close down the infamous Chicken Ranch, a La Grange brothel. The incident provided the basis for the Broadway play and Hollywood movie The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas.

Current journalism students at Tarleton have similar aspirations of making a mark. They pay tuition, attend classes, and learn how to investigate and write stories that expose the human condition and perhaps lead to change. Tarleton promotes “real-world experiences applied to learning.” Posters with that slogan can be seen hanging in buildings all over campus. And it’s not false advertising — student journalists are currently getting a real-world experience in an up close and personal way.

Their requests for public information have rankled school officials even as some of their stories have shed light on problems such as unreported campus crimes. Now their instructors are at risk of losing their jobs, including Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Dan Malone, who was hired five years ago to beef up the journalism department.

“I believe we should have the right to have students file open records requests,” said Malone, a former Fort Worth Weekly staffer.

Tarleton is part of the Texas A&M University System. At the request of Tarleton president Dominic Dottavio, system attorney Andrew Strong interpreted a school policy to mean that instructors can’t direct students to submit open records requests. The requests are an integral part of a journalist’s job and are included in the school’s curriculum and textbooks. Since then, A&M officials have tried to downplay the ruling, saying students themselves aren’t prohibited from submitting the requests.

Still, a national furor among journalists and journalism educators developed quickly. University of Missouri School of Journalism associate professor Charles N. Davis described the policy as authoritarian. “I find that policy stunning — to threaten someone with discipline up to firing for exercising one’s legal right to access public information.”

The Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas, a nonprofit group that promotes public access to government records, wrote a letter to Strong on Dec. 2 asking him to “immediately suspend the applicability of this interpretation to professors who … instruct or assist students in the filing of public information requests.”

Newspaper editorialists got busy, including at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, where an editorial was topped by the headline, “How can you tell when an Aggie policy is absurd?”

Newspaper editorialists got busy, including at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, where an editorial was topped by the headline, “How can you tell when an Aggie policy is absurd?”

A&M hasn’t tried to enforce its new interpretation of policy but appears to be treading slowly and carefully now that so many eyes — and newspapers, TV programs, and web sites — are focused on what happens next.

Hanging in the balance, many believe, is the public’s right to know, a lesson not lost on Tarleton students.

“As a student of journalism, I don’t really like it when anyone tries to restrict the flow of information or hinder people’s right to know anything,” said communications senior Drew Eubank.

Hogtying an instructor cuts at the core of what academic freedom and education are all about, said Rachel Dudley, a communications senior whose news articles about the cancellation of Corpus Christi, a play involving a gay Jesus character, helped draw national attention to the university earlier this year.

“A professor shouldn’t be inhibited,” she said. “They teach by example. If you’re teaching journalism, and freedom of information requests are part of journalism, then a professor ought to be able to explain what an FOI [request] is and when it should be used and how to go about doing that.”

Malone and other Tarleton journalism instructors are worried. Nobody is embracing martyrdom or career suicide. They like teaching at Tarleton. They want to stay. But they also want to share with students the best methods of researching stories, and that includes instructing them on submitting public information requests. The Public Information Act gives the public the right to access certain government records, including those at public universities.

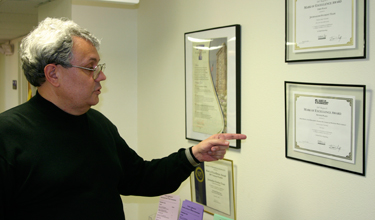

Malone was hired to help create a journalism program and instill real-world experience and journalistic passion among students interested in news media careers. There’s no denying Malone’s credentials. He’s won numerous awards in the past 30 years during stints with the Weekly, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and The Dallas Morning News, where in 1992 he won the most coveted award of all — the Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting. The Pulitzer was awarded for a series of stories on civil rights abuses by law enforcement agencies, for which he and a co-worker filed numerous open records requests.

“He is one of the most outstanding people we’ve ever had at [Tarleton] in terms of teaching university students about journalism,” said Charles Howard, head of the communication studies department.

Prior to 2006, the university offered a basic journalism class but little more in the way of advanced new writing. That changed with Malone’s hiring and the creation of an intensive journalism program.

“I said, ‘Your job is to make this the best journalism program of any school our size in the state of Texas,’ ” Howard recalled telling Malone five years ago.

Tarleton’s program doesn’t have the clout and financial backing of institutions such as the University of Texas at Austin, the University of North Texas’ Mayborn School of Journalism, or Texas Christian University’s Scheiffer School of Journalism. (A&M eliminated the journalism program at its main campus several years ago.) But Howard still wanted Tarleton’s program to compete with the best, and he knew landing a top-notch investigative reporter with hands-on experience could jumpstart the program.

Malone had already proven his teaching skills as an adjunct professor at the University of North Texas and as a visiting professional-in-residence at the University of Texas at Austin.

One of those projects at UNT was an investigation of campus crime around the state. Federal law, prompted by the rape and murder of Jeanne Clery in her Pennsylvania dorm room, requires colleges to disclose campus crime statistics to let students know of dangers. Some colleges, however, hide that information or claim ignorance about the requirement to track statistics. The project was done as part of the Light of Day program created by the Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas in 2004, with major input from Malone. Some of the resulting stories were published by the Weekly.

Light of Day projects connect journalism departments at various colleges, and students collectively research and obtain public records for real-world stories. Malone’s UNT students spotlighted failures by several colleges, including the University of Texas at Arlington, to comply with the Clery Act. Another statewide project involved investigating law enforcement agencies’ use and abuse of Tasers. Those results were also published by the Weekly. Both won regional and national awards.

Howard saw a jewel in Malone and wanted him to teach Tarleton students how to become journalists.

“What [Malone] has done with the journalism program is he’s made it take a quantum leap from nothing to something that everybody in this community should be proud of,” Howard said. “The students have learned an extraordinary amount — the evidence is clear because our students have won awards nationally from the Society of Professional Journalists.”

One of Malone’s students, Erin Cooper, filed public information requests at Tarleton about crime statistics, which began a long battle with the university over the records.

“It was a volunteer thing — in no way did Dan instruct me to [submit an open records request],” Cooper recalled recently. “No one had ever looked into this information at Tarleton before, and Dan asked if anybody would be interested in researching this, and I was the lucky one who raised my hand.”

“It was a volunteer thing — in no way did Dan instruct me to [submit an open records request],” Cooper recalled recently. “No one had ever looked into this information at Tarleton before, and Dan asked if anybody would be interested in researching this, and I was the lucky one who raised my hand.”

Eventually, Malone’s class received information that showed the university wasn’t accurately reporting sexual assaults, burglaries, or drug violations. That sparked a string of news articles by students, which led to regional and statewide journalism awards, including the Society of Professional Journalists’ Mark of Excellence Award.

Students were thrilled. The university, not so much — it was fined $137,500 by the U.S. Department of Education for not accurately reporting on-campus crime, the first time a Texas university was fined for violating the Clery Act. The university cited ignorance of the law and appealed the fine, which was later reduced to $27,500.

Cooper had been uncertain about her career choice until she enrolled in Malone’s class.

“Dan is all about educating his students and presenting them with the tools they need to get the job done in the real world,” she said. “Researching that story and doing other stories, I really fell in love with writing, and it influenced what I wanted to do with a career.” Now she’s a reporter at the Empire-Tribune in Stephenville. Several other reporters involved in the Tarleton investigation have gone on to news media jobs.

The recent policy interpretation seems odd to Cooper.

“Preventing students from making open records requests hinders their education,” she said. “Students need to have the ability to request information they need and to understand that they have a right to that information. When you get out into the real world as a young journalist, having that understanding really gives you leverage and shows you what a difference a journalist can make in a community.”

Less diplomatic is Lucy Dalglish, executive director of the Reporters Committee For Freedom of the Press, a nonprofit legal defense and advocacy organization based in Arlington, Va.

“It always astonishes me when educational institutions, which should be doing all they can to encourage the development of young journalists, do something so boneheaded,” she said. “If you don’t want to teach young reporters how to use basic public records laws, you have no business running a journalism program. It is a fundamental tool.”

After the on-campus crime stories, things quieted down — but not for long. Investigative journalists who bring their skills to universities often anger bosses when stories hit too close to home.

“It’s part of the job description,” said Craig Flournoy, Southern Methodist University journalism professor and another Pulitzer Prize winner.

Flournoy learned that firsthand while teaching journalism at Sam Houston State University in 1997 and 1998. There’s a reason he didn’t stay long. His students researched and wrote articles about un-prosecuted rapes on campus.

“Their reporting helped eventually send a guy to jail,” he said. “It thrust the issue of sexual assaults on campus to the forefront.”

That’s good — right? Well, no, not if your job is to boost enrollment and please donors.

“Bosses don’t really mean it when they tell you to do investigative journalism, because it generally pisses off the powers that be,” Flournoy said. “Dan Malone is an absolutely terrific reporter and teacher, and he’s teaching kids to do journalism the only way he can really teach them — by doing journalism.”

In March, Tarleton theater student John Jordan Otte (pronounced oi-tay) planned to direct a performance of the play Corpus Christi for a class project. The performance wasn’t intended to be open to the public, but when news of its depiction of a gay Jesus began to spread, Tarleton administrators found themselves once again embroiled in controversy. Stephenville’s conservative residents wrote angry letters, alumni registered complaints, and a local Christian radio station fielded calls of protest.

Publicly, Tarleton president Dottavio lamented the play’s content but said he would allow it to be performed in the class because the university was committed to protecting free speech. But he was standing in the eye of a storm.

Otte’s theater professor eventually canceled the play, citing concern for the safety of his students. However, Dudley, then one of Malone’s students, wrote an article for the Weekly, pointing out that Stephen Hotze, president of the Conservative Republicans of Texas, was publicly thanking Gov. Rick Perry and Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst for their involvement in killing the production. Dewhurst had been outspoken in his opposition to the play, which he considered blasphemous.

“Every citizen is entitled to the freedom of speech, but no one should have the right to use government funds or institutions to portray acts that are morally reprehensible to the vast majority of Americans,” Dewhurst said in a written statement.

Hotze wrote on a political blog site that “behind-the-scenes work” by Perry and Dewhurst helped kill the play. Tarleton theater professor Mark Holtorf disputed the claim, saying he alone had canceled the play for security reasons.

“Gov. Perry did not affect my decision, and Lt. Gov. Dewhurst did not weigh in on my decision to cancel the play,” Holtorf told Dudley.

Perry, too, denied any role in the cancellation. But suspicion was cast, and student reporter Dudley did what she’d been taught in class — she filed an open records request at Tarleton asking for phone records to see if calls had been placed between Dottavio and either Perry or Dewhurst prior to the play’s cancellation. Tarleton said it would cost $2,627.50 to provide the records.

Dudley refashioned her request, narrowing the search parameters, got the fee reduced, and eventually received the records. She had learned how to make open records request in her communications classes at Tarleton but wasn’t told to submit one for her story on the play’s cancellation, she said.

“I just submitted it,” she said. “The first one I didn’t even do right, and so I learned how to do it the hard way.”

She found no evidence of phone calls between Dottavio and Perry or Dewhurst. However, in a subsequent Weekly story in late April, Dudley reported that “in the hours leading up the cancellation decision, Dottavio received five calls on his cell phone from top officials in the Texas A&M University System.”

Meanwhile, university administrators were beginning to chafe at the number of public information requests coming from students and the amount of time it took to research them and respond — not to mention, perhaps, the embarrassment they were causing. Dottavio asked the A&M System whether faculty members could direct a student to submit a public information request to Tarleton under the Texas Public Information Act.

On Oct. 27, A&M attorney Strong responded: “The answer to the inquiry is ‘no.’ ”

A rule that’s been on the books for a dozen years prohibits university employees from making public information requests of the system while acting in their official capacity. Therefore a faculty member may not “direct” a student to submit a request, Strong said.

A rule that’s been on the books for a dozen years prohibits university employees from making public information requests of the system while acting in their official capacity. Therefore a faculty member may not “direct” a student to submit a request, Strong said.

A&M System spokesman Rod Davis downplayed the interpretation, saying it doesn’t stop students from submitting requests. But that did little to calm the concerns growing among journalism and open government groups that questioned the legality of preventing someone from seeking public information.

“What you have is a university, by rule, prohibiting their faculty from performing a legal act, an action specifically sanctioned by the Texas Public Information Act,” said Joe Larsen, a Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas board member and a Houston-based First Amendment attorney. “The only purpose for this could be to protect itself against embarrassing disclosures unearthed by their own journalism students, which flies in the face of journalism, teaching journalism, and the concept of limited government.”

University officials complained about the time and costs involved in gathering the requested information, a common excuse among governmental entities that resist the disclosure of information.

State records show that in 2008 and 2009, Texas governmental agencies fulfilled more than 4.3 million requests, collected more than $3 million in fees related to providing the information, and spent more than 14,000 hours of employee time fulfilling the requests. Sometimes agencies seek an attorney general’s opinion on whether the law requires them to release certain information. In those 3,500 cases, about 6,300 hours of employee time across all state government was spent redacting information.

When those numbers are broken down, Tarleton students don’t appear to be excessive in their use of public information requests. In fiscal 2010, Tarleton received 91 requests from all sources, compared to 863 at Texas A&M University in College Station, 101 at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi, 106 at Texas A&M-Kingsville, and 2,960 at the University of North Texas.

“That’s the price of living in a participatory democracy,” Larsen said. Still, he stopped short of saying the A&M System is breaking the law with its policy.

“That’s the price of living in a participatory democracy,” Larsen said. Still, he stopped short of saying the A&M System is breaking the law with its policy.

“The A&M system has the right to restrict the free speech of its employees in the employment setting,” he said. “But I would add that freedom of speech is also the freedom to receive information. And they are impinging on the free speech rights of their students. I also see that faculty is only prohibited from recommending requests directed to the system. Therefore this could violate the public information act that restricts inquiring into the purpose of public information act requests.”

Legal or not, A&M’s policy interpretation is “wrongheaded,” he said. “Texas A&M should be embarrassed.”

Both the Student Press Law Center and the Society of Professional Journalists are writing letters to the A&M system decrying the policy, which SPJ vice president Neil Ralston characterized as “absurd.”

“I’ve been on the board more than five years, and I’ve been with SPJ much longer than that, and this is the first time I’ve heard of a school trying to restrict an instructor in this way,” he said.

Journalism watchdog groups aren’t the only ones concerned.

Dudley, a Tarleton junior, admires Malone and called him a “wonderful asset.”

“He’s an excellent professor with a vast wealth of knowledge that students have the opportunity and privilege to tap into,” she said.

But she worries that the university’s heavy-handed dealing on the open records matter taints its credibility.

“It causes a lot of red flags to be raised for me as a journalism student about the university and about what’s going on behind the scenes,” she said.

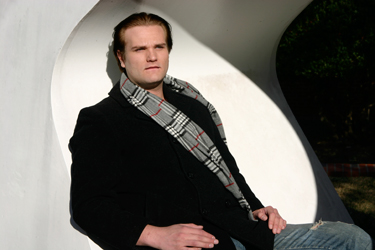

Another student concerned about the policy interpretation is Otte, who had planned the performance of Corpus Christi. The Tarleton junior didn’t speak to the press much in April after the play was cancelled. He said he was trying to protect his theater professor and the university in general. He received hate letters and threatening e-mails for a while, he said, but things settled down, and he has continued his theater education in relative obscurity.

“The town moved on to something new,” he said. “My group never got the opportunity to do the play. It’s disappointing, but what can I do?”

Hearing about the university’s attempt to quash open records requests brought back some of the anger he felt when he was prevented from directing the play of his choice for a class assignment. This time he’s more inclined to speak up.

“It affects the journalism department a lot, but eventually it will affect every aspect of our campus,” he said. “It’s just one step closer to them silencing our professors. They work on this campus in a fear-based administration where they fear being fired for opening their mouths. This is an official policy promoting that.”

Then again, the school promotes its real-world experiences, and Otte received plenty of that.

“I learned a lot,” he said. “I learned about lobbying, free speech, and what’s actually free and what’s not — something I never could have learned in a classroom.”

Malone, Howard, and Dean Minix, dean of the College of Liberal & Fine Arts, met with Tarleton provost Gary Peer last Friday to discuss the A&M System’s policy interpretation and its effect on classroom instruction. They’d asked for more details on the attorney’s interpretation, specifically as to what constitutes “directing” a student to file an open records request.

“We’re going to get clarification of a clarification,” Howard said.

However, they’d received no further guidance by press time.

“These gentlemen [Howard and Malone] are going to continue to do what they have done in the past until we get further clarification from system counsel,” Minix said. “I would think that the teaching and the instruction of filing a freedom of information [request] is part and parcel with a standard curriculum in these type of courses.”

“It’s absolutely standard,” Howard said. “It’s in the master syllabus that we have to file at the university on several of these courses.”

Malone said he isn’t convinced he’s ever directed a student to fill out a public information request, although he wants further clarification of what the A&M System means by “directing.”

“I have wracked my brain to remember over the five years I’ve been here if I’ve ever said, ‘You have to file this request,’ and tied it to a grade,” he said. “I don’t remember ever having done that. I’ve asked my students, and they say, ‘No, you always ask for a volunteer or say, ‘You might consider doing this.’ I don’t think I’ve ever actually done what [the A&M System is] saying we shouldn’t do.”

Several of Malone’s current and former students interviewed for this story said the same thing — he told them how to submit open records requests in general but didn’t tell anyone that they had to submit one as part of a class assignment.

Former student Eubank passed Malone’s classes without ever filing a request.

“I just never wrote a story where it was necessary,” he said. “I don’t remember him telling anyone specifically to file a specific records request, but we learned about the process.”

Davis, the Missouri journalism associate professor, worked as a Morning News intern years ago and recalled being in awe of Malone.

“Malone was on the famed investigative desk,” he said. “I know from experience what an unbelievable journalist the guy is. When you hire a really good journalist to teach kids to do really good journalism, guess what’s going to happen — really good journalism. It’s the height of naiveté to hire Dan Malone and be shocked when he produces hard-hitting stuff.”

Tarleton should be proud of Malone and the impact he’s having on students rather than trying to silence him with policy interpretations, Davis said.

“That just smacks of authoritarianism,” he said. “I can only presume the goal is to shut people up and get them to not ask for public information from the system.”

Editor’s note: Fort Worth Weekly editor Gayle Reaves, who has worked with Dan Malone off and on for more than 20 years, is currently working with various journalism organizations to raise objections to the A&M counsel’s ruling.