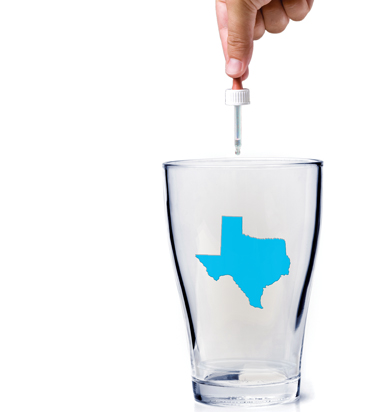

“Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting over.” — attributed to Mark Twain

“People are drawing a line in the sand,” Marie Day said.

What the South Texas activist really means is, they’re trying to draw a line in the water.

If that sounds difficult, think of it as a metaphor for post-millennial water politics in Texas, where populations are growing, aquifers are receding, laws are murky, and the urban-rural divide is reopening along old fault lines. Across the state, cities need more water, and almost the only place to get it is the country — or perhaps the countryside one state over. And who can blame neighbors for looking at one another warily, when the general rule is that he who drills first and biggest can legally suck out the water not only from under his land but yours as well?

One result of all that is a series of major water pipeline projects that are being proposed, built, and fought over in many parts of the state, as cities — and commercial marketers — reach out to obtain the rights to water underneath Texas farms, ranches, forests, and small towns. To some grassroots leaders, it looks like just another version of the Trans-Texas Corridor, the Rick Perry-supported (and now mostly abandoned) toll roads megaproject that would have cut a huge swath through the state and required the taking of millions of prime acres by eminent domain. That time, environmentalists, small town officials, and farmers and ranchers teamed up to oppose it. This time, the battle lines are different and a lot more complicated.

One result of all that is a series of major water pipeline projects that are being proposed, built, and fought over in many parts of the state, as cities — and commercial marketers — reach out to obtain the rights to water underneath Texas farms, ranches, forests, and small towns. To some grassroots leaders, it looks like just another version of the Trans-Texas Corridor, the Rick Perry-supported (and now mostly abandoned) toll roads megaproject that would have cut a huge swath through the state and required the taking of millions of prime acres by eminent domain. That time, environmentalists, small town officials, and farmers and ranchers teamed up to oppose it. This time, the battle lines are different and a lot more complicated.

“It doesn’t matter whether it’s surface or groundwater, the conflicts are the same,” said Ronald Kaiser, Texas A&M University professor and chair of the university’s water program. He is acknowledged as an expert in Texas’ maze of water laws and regulations. “What’s driving this is population growth and the need for urban areas to firm up their water supplies.”

Water fights have been going on in Texas longer than it’s been a state, but in recent years the battle has gotten more confusing, and the stakes are getting higher. With little surface water left unspoken for in the drier parts of the state, groundwater is coming to look more and more like liquid gold, and the more valuable it gets, the more intense the battle. Water rights that had once been taken for granted are now being fought over in appellate courts, with water marketers, farmers and ranchers, and city dwellers all watching intently for the outcome.

“The Texas water code is broken,” said Day, a landowner, chairwoman of the nonprofit Lavaca County Taxpayers Inc., and a leader of the Independent Texans group. “It has pitted rural values against urban values.”

Kathy Chruscielski comes down on the opposite side from Day on some water issues, but not because she’s a lawn-watering urbanite. She has four acres in eastern Parker County, just outside Fort Worth. A few years ago, with wells all over the county starting to dry up, she and others educated themselves on the problem and on the amount of groundwater available in their portion of the Upper Trinity aquifer.

If groundwater resources were allotted proportionately to surface acreage, she said, the aquifer could sustain the water needs of about one house to every two acres, about the size of the properties in her own neighborhood. “But in the neighborhood next to us, they have roughly three-quarter-acre lots,” she said. “Do the math. They’re taking my water. They’re

using water from under my subdivision. It’s not a sustainable situation.”

A few weeks ago, two reports by major national environmental research organizations suggested that a number of major American cities could be facing serious water shortages within the next few years. One of the cities near the top of the list in the ratings for water-shortage risk was Fort Worth, based in part on the heavy reliance by the Tarrant Regional Water District on water from reservoirs, which are much more susceptible to drought than aquifers. Another problem: Fort Worth and Dallas both are betting on a plan to draw major quantities of groundwater in the future from Oklahoma, a proposal that is being fought in court and by Oklahoma legislators. Tarrant district officials dispute the conclusions and some of the facts in the report, but it has raised some eyebrows around town.

One way or another, change is coming. Most observers figure the Texas Legislature, beset with a budget crisis and a redistricting fight, won’t even dip their toes in water issues when the session opens in January. But the two state agencies that have the most to do with refereeing the water fights come up for sunset review this year, and changes are being suggested in the way they do business. And on at least one side of the issue, landowners (and marketers), worried about what they see as attempts by conservation agencies to limit their right to use groundwater, are organizing and raising money to put their views across.

For farmers and city leaders alike, water is the ultimate factor limiting human existence, economic activity, and societal growth. “People need water — it is a fundamental truth,” said Fort Worth consulting hydrologist Ranjan Muttiah. “It’s not like if you run out of Coke you can switch to Pepsi. It is an

irreplaceable resource.”

Many parts of the country, especially in the drier Southwest, are facing water- supply shortages, and much bigger problems may be around the corner, as global warming leads to more violent weather swings, including deeper droughts. But few states are stepping into that future with Texas’ combination of water needs, population growth, and a byzantine system of water regulation.

“People will point to Texas and say, ‘We’re so glad we have our own system in place,’ ” Kaiser said.

Years ago, Kaiser once made a presentation to the Texas Senate’s Natural Resources Committee suggesting that one partial answer to Texas’ burgeoning water-supply problems would be to slow down or not encourage growth in the drier parts of the state, where population pressures were threatening to outstrip local renewable supplies.

“I was lucky to make it out of the room alive,” he said.

So much for the simplest — and most politically poisonous — solution to the state’s water-supply problems.

“The dilemma is that cities are not going to stop growing in this state, and it takes a long time to develop water resources,” Kaiser said. “The legislature cannot afford to let cities go dry.” There’s a series of factors and strategies to consider after that realization and a long list of pissed-off people to deal with. “But ultimately the legislature has to face reality,” he said. “They are going to have to move water from areas with excess to areas of need.”

Pumping rural groundwater to cities via pipelines clearly isn’t the only strategy for building municipal water supplies. The state water board, major water districts, and cities have been working for many years on conservation strategies, water reuse options, and desalinization plants. But another traditional major option, of building new reservoirs, isn’t as much of an answer as it used to be.

Robert Mace is the state water board’s deputy executive administrator for water science and conservation. In the western parts of the state, he said, it’s true that most of the available surface water is spoken for, so that new reservoirs aren’t an answer there. “In the eastern part, there is still water,” he said, but each new reservoir project “is a tougher fight.” (A South Texas group is currently fighting plans to build a dam and reservoir on the Lavaca River, for instance.) Every reservoir floods land that is important to someone, and they’re not making any new farmland in Texas these days.

Moving water around the state in pipelines is nothing new — the Tarrant district brings water up from its Richland Chambers Reservoir about 90 miles southeast of Fort Worth, and Panhandle cities get major amounts of water via a 300-plus-mile pipeline from Lake Meredith.

Moving water around the state in pipelines is nothing new — the Tarrant district brings water up from its Richland Chambers Reservoir about 90 miles southeast of Fort Worth, and Panhandle cities get major amounts of water via a 300-plus-mile pipeline from Lake Meredith.

But groundwater pipelines are a somewhat different animal. Reservoirs are major and sometimes controversial projects, but at least the parameters of what’s being taken are clear. Thanks to Texas’ century-old “rule of capture,” however, those who buy rights to groundwater don’t necessarily have to stop at the surface fenceline — at least until the last few years, the law was that surface owners could claim as much water as they could capture from underground sources, regardless of how far beyond their own property lines that underground pool extended. Oilman T. Boone Pickens kickstarted the trend years ago with his grand plans to send billions of gallons of water from the West Texas portion of the Ogallala aquifer to major Texas cities (although he’s found no takers yet).

Now oilman and former gubernatorial candidate Clayton Williams wants to pipe groundwater from Fort Stockton to Midland and Odessa. And residents of the Bastrop area are fighting plans for a $400 million pipeline that would send a lot of their groundwater to the San Marcos-San Antonio area, in what the Austin American Statesman described as a massive deal. San Antonio, in particular, needs another reliable water source besides the overextended Edwards Aquifer and is also working on a deal to buy and pipe in groundwater supplies from Gonzales County. In southwest Texas, around Brackettville, the fight over who would get permits to sell water to the cities or to irrigate their crops got so contentious a few years ago, one newspaper reported that “neighbors no longer speak to each other.”

Around Bastrop, “Those who live in the Lost Pines area are very deeply concerned” about the sale of their groundwater to cities along the I-35 corridor, said Linda Curtis of Independent Texans. “The farmers and ranchers here are already under siege from urban sprawl.” The scenic area of hills and rich farmland has just come through a major drought, she said, “and it looks like we are headed toward more.”

Kaiser said he jokingly refers to there being three kinds of people: “People who have leased or sold their water rights and are happy to get the money, people who would like to do it, and a third group that thinks the others are absolute pariahs.”

Luke Metzger, the director of Environment Texas, said he’s convinced such skirmishes will only increase. “Despite the influence of people like Pickens, water is a very local issue,” he said.

Metzger also noted that the increasing demands on Texas rivers and aquifers are endangering the animals and habitats of Texas estuaries. “Even before the new demands, there was already far too little water flowing in our rivers down to the coast, feeding our estuaries. That has contributed to the deaths of endangered whooping cranes, because there’s not enough water [to sustain] their food supply,” he said. Lawsuits have already been filed against the state for failing to protect those water flows, he said. “There’s a process in place” that’s supposed to protect the endangered species and areas, he said, “but it’s inadequate.”

It’s the same word a lot of people are using to describe Texas’ water conservation and regulation process.

Water in nature moves — creeks flow into rivers, runoff seeps down into aquifers, and even the water in aquifers is not static. But, at least as it involves water, Kaiser said, the Texas legal system “doesn’t recognize science.” Instead of treating all water as part of the same system, Texas law “pigeonholes it into surface and groundwater, with two totally different systems of management.” The result, in many cases, he said, has been “internecine warfare” among state and local water-related agencies.

Texas’ rule of capture dates back to 1904. Only in the last few years has the legislature, recognizing the Wild West nature of what was happening to the state’s finite groundwater supplies, authorized the creation of groundwater conservation districts. Like so many other small, single-function government bodies in Texas, the districts — there are about 90 of them now — tend to get overlooked and yawned at, until they land in the middle of controversy. Which is exactly where the groundwater districts are now, hip deep, for one key reason: They have the power to issue or deny permits for water drilling.

After legislators realized the groundwater districts were too small to provide true regional planning for water needs, they added another layer — something called groundwater management areas, essentially groups of groundwater districts. And through the GMAs, groundwater district officials were required to plan for the future — to plan for how much water they want left in their aquifer in 20 years or 50 years down the road and how to make that happen.

That means you have agencies that not only can deny permits, but are supposed to implement plans that, indeed, might require them to disapprove of wells and projects that could drain their part of an aquifer too fast.

That means you have agencies that not only can deny permits, but are supposed to implement plans that, indeed, might require them to disapprove of wells and projects that could drain their part of an aquifer too fast.

And now the landowners, aquifer management groups, and water marketers are getting worried. In Texas, as soon as you start doing something that can be interpreted as messing with property rights, the hackles go up. And water, once captured, is increasingly valuable property.

Chruscielski, the Parker County activist, for several years operated an online newsletter called PARCHED, about local wells and groundwater problems. When Parker and several surrounding counties created their own Upper Trinity groundwater district, she said, “I was hoping my work was done.”

But now, she said, landowner and water rights owner groups are “trying to roll back” the law that gives groundwater districts a say in controlling permits, by challenging those actions as being a taking of valuable private property — that is, water.

“Any time you say ‘property rights,’ you get a lot of Tea Partiers very excited,” she said. “The property rights coalitions are very well funded. … They’re tapping into the whole anti-government sentiment.” Water rights became an issue in the county judge’s recent re-election campaign, she said. And she’s thinking she may need to reactivate her newsletter.

If groundwater districts can’t regulate the pumping out of aquifers, she said, opponents of the conservation districts “may find they have shot themselves in the foot.” In Parker County, where many wells have run dry, she said, “we can’t go any deeper. We are at the bottom of the drinkable water [stratum].”

Jason Skaggs is executive director for government and public affairs for the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association, one of the key members of the groundwater rights group. He said his association and several others became concerned about a year ago when some groundwater district officials “began to question whether landowners had vested interest in the groundwater beneath

their property.”

Their coalition, he said, believes the statute needs to be clarified. “We feel like it’s a disincentive, if we don’t clarify the ownership issues — that people will be out here scrambling to get their wells drilled out of concern that they have to beat the next guy.” They don’t want to change the rule of capture, they want to shore it up.

The water-as-property issue may be settled soon by the Texas Supreme Court. A suit filed by two farmers in the Edwards Aquifer region near San Antonio challenges the aquifer authority’s right to deny the farmers the full amount of water they wanted to drill for. The suit, which alleges that such a denial amounts to the taking of private property, was argued before the state’s top civil appellate court in February, but there’s been no ruling yet.

“We don’t want to wake up 10 or 15 years from now and look back and say, ‘We quietly let our rights get taken away from us,’ ” Skaggs said, “and some water marketer or city has taken our

rights, taken our water because we didn’t claim ownership.”

Statewide, the groundwater control debate has become so contentious — and the structure for dealing with it so inadequate and patched-together — that staffers of the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission have advised the legislature that it “threatens the [Texas Water Development] Board’s fundamental ability to support the development of the state’s water resources.”

The sunset staff report uses phrases like “fundamentally flawed” to describe the appeals process facing those who disagree with groundwater officials’ pronouncements on aquifers. The separate systems for dealing with surface and groundwater conditions “impedes the board’s ability” to do statewide water planning. And perhaps most telling of all, the sunset staff found, the water development board doesn’t have the information it needs to figure out if, indeed, Texans are doing enough conservation and water management to actually enable the state to meet its water needs in the future. Nor does the board have the tools to tell who is really using the most water in certain areas and doesn’t have the power to take action on its own to protect or develop the state’s water supplies, the report said.

![Muttiah: “It’s not like if you run out of Coke you can switch to Pepsi. [Water] is an irreplaceable resource.” Naomi Vaughan feat_3](https://www.fwweekly.com/wp-content/images/stories/images/11-10-2010/feat_3.jpg) Kaiser, the A&M water expert, said many other Western states with water-supply problems as serious as those of Texas already have more simplified water-management agencies — one water czar, in effect, to keep track of and regulate both surface and groundwater supplies. In Colorado, for instance, if a person’s or business’ activities “will impact river flow by one half of a percent in 100 years,” state regulation kicks in.

Kaiser, the A&M water expert, said many other Western states with water-supply problems as serious as those of Texas already have more simplified water-management agencies — one water czar, in effect, to keep track of and regulate both surface and groundwater supplies. In Colorado, for instance, if a person’s or business’ activities “will impact river flow by one half of a percent in 100 years,” state regulation kicks in.

There are other states with fragmented systems like Texas’, he said, but they are all in more water-rich areas of the country.

Kaiser believes that water will always be considered private property in Texas. “This notion of private ownership of water is so entrenched, “ he said, “it would take a monumental shift in political ideology to change it.”

But that doesn’t mean the old political alliances will necessarily apply. “I think we’ll start to see even very conservative Republicans step up to protect water rights in their areas,” Metzger, of Environment Texas, said. “We may start to see some interesting alliances here.”

It’s by no means a new alliance, but the groundwater ownership fights do change the nature of some old enmities. The rural versus urban thing, for instance — farmers point out that city folks are huge wasters of water, with all their sprinkler systems and car washes and ornamental ponds and fountains. Agriculture, on the other hand, is the biggest user of water, and more efficient ways to irrigate and the growing of less water-intensive crops are part of the equation.

As Kaiser predicted, the cities are likely to win water rights ultimately. But if so, in many cases it will be the farmers and ranchers — the traditional landowners — selling that water to the cities or the water marketers. And all the water planning and water trading in the world may not help save some cities, if resources like the Ogallala are indeed allowed to run dry, which could happen, under some scenarios, in the next 50 years.

Muttiah, the Fort Worth hydrologist, said all the climate models show that global warming is speeding up, which for Texas, among other impacts, will cause the intensification of weather cycles — more intense storm patterns, but also more drought. Which means that water planners probably ought to be taking much grimmer predictions into account when deciding what the worst drought is that they should be prepared for.

Mace, the water board executive, said the state’s water-planning process does take the possibililty of severe drought into consideration. Implementation is the tough part, he said. “If Texas was hit with a ‘drought of record’ like we saw in the ’50s, we wouldn’t be ready for it,” he said. “And a big part of the problem is money.” Indeed, the sunset staff report pointed out that the state water board is fast running out of bond money.

Climate change, Muttiah said, could help tip the region into what he called a “megadrought” that could last for decades. Such droughts have happened here before, he said, perhaps 900 or 1,000 years ago. Those kinds of droughts are believed to have killed off civilizations in some parts of the world in the past, he said.

If Texas’ water resources are

accepted as finite, there are many measures that governments and industries can take to adjust — more conservation of water, clearly, but also more reuse of water and more adaptation. Just as the trend now is to build structures that are more energy-efficient, Muttiah said, buildings could also be constructed to be more water-efficient — harvesting rainwater off roofs and even installing water-treatment systems, to reuse water. Some of those things, he said, “are already in the works.”