On some mornings, Concepcion Arellano wakes up feeling unable to breathe. “My heart races and my body shakes,” the 86-year-old said. She calls the condition susto — “pure dread that is like you lost your soul.” When it happens, she doesn’t reach for a pill bottle, however. She calls her daughter to take her to the El Sol Botanica on Jacksboro Highway. And there, Rosa Vargas goes to work.

Vargas, a short, heavy woman with piercing eyes, is Arellano’s curandera — her healer. And Arellano places as much faith in Vargas’ work as any patient of mainstream medicine places in a degreed doctor.

Vargas, a short, heavy woman with piercing eyes, is Arellano’s curandera — her healer. And Arellano places as much faith in Vargas’ work as any patient of mainstream medicine places in a degreed doctor.

“She is a wonderful healer. I’ve seen her do so many things for people,” Arellano said. “And as soon as Rosa puts her hands on my arms, I begin to calm down. I begin to feel I can breathe again. If I didn’t have her, I am sure I would be dead by now.”

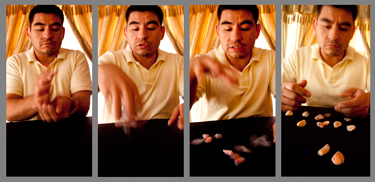

Vargas said that for susto — dread, or soul loss — she first gives her client a calming tea of yerbaniz, Mexican marigold mint similar to anis. After that she sweeps the person with piedra alumbre, alum rock, daily for three to nine days, depending on the severity of the fear. At the end of the treatment, the alum rock, which is thought to have absorbed the susto, is burned in hot coals, taking with it the fear or trauma that affected the patient.

You won’t find susto described in many medical textbooks (except, perhaps, for those dealing with psychology), but many Hispanic people consider it a genuine condition and see the relief brought to sufferers as genuine healing.

It’s just one part of the tradition of folk healing that is thriving in Hispanic communities from the southern United States down through Central and South America and the Caribbean — and in Fort Worth, via a half-dozen shops, most of them clustered around Azle Avenue on the North Side.

It’s just one part of the tradition of folk healing that is thriving in Hispanic communities from the southern United States down through Central and South America and the Caribbean — and in Fort Worth, via a half-dozen shops, most of them clustered around Azle Avenue on the North Side.

The candles and amulets, the beads and statues and packaged herbs that fill the little botanicas seem like so much snake oil to outsiders. But curanderismo has its backers in the scientific community.

“The curanderos and curanderas who work in Fort Worth are really a mental health behavioral support system that is essential to the Mexican-immigrant and Mexican-American community,” said Antonio Zavaleta, assistant provost and professor of anthropology at the University of Texas at Brownsville. “More than that, many are also serving the community as physical doctors,” he said. “There are some who are experts in medicinal plants; someone else might set bones; others deliver babies. It is a small group of specialists who have spent many years learning to do what they do.”

Even the local curanderas acknowledge, however, that there are charlatans among the healers — and perhaps a few who are worse than fakers.

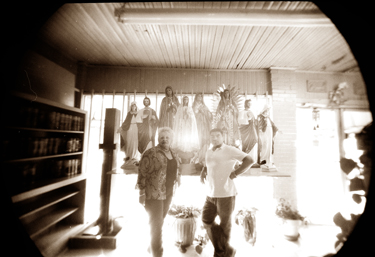

The sign in Spanish in the window at the botanica San Judas Tadeo promised spiritual cleansings, physical cures, love potions, card readings, protection from immigration authorities, and luck in all endeavors. Behind the glass, statues of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, saints and angels waited.

The sign in Spanish in the window at the botanica San Judas Tadeo promised spiritual cleansings, physical cures, love potions, card readings, protection from immigration authorities, and luck in all endeavors. Behind the glass, statues of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, saints and angels waited.

Inside, the bright colors of candles represented different types of luck: love, money, work, health, family. The statues stacked on shelves were mostly Catholic images, but others were more exotic: Jesus Malverde is the fabled Mexican Robin Hood who has become the patron saint of drug dealers. The robed skeleton carrying a scythe in one hand and either a globe or owl in the other is Santisima Muerte, Saint Death, a Mexican version of the Grim Reaper but also the patron saint of souls, said to be capable of performing enormous miracles or causing terrible sickness and death to one’s enemies. The store’s counter was covered in prayer cards, amulets, and packaged herbs. On the wall behind were dozens of strings of rosary beads. And as at other botanicas, a curandero’s services are available, with treatments provided in a private room behind the counter. Botanica operators estimated that another dozen or so curanderos in Fort Worth work independently from their homes.

Vargas says her clients come to El Sol for help with an array of physical and emotional problems but particularly to be spiritually cleansed of negative energy directed at them from someone else. “They’ve been affected by things like mal ojo, the evil eye, or envidia, jealousy,” she said. “Those things have real effects on people. They make them sick or cause them to lose their jobs.”

To eliminate the negative energy, Vargas “washes” the clients with a quartz stone, sweeping it around their bodies to attract the negativity. “I know that probably sounds crazy, because I am just a regular person in normal life,” Vargas said. “But when I begin to work on someone, I go into a trance and a sort of spirit enters me. I ask God to help me heal, and a power comes through me, and I am able to eliminate the negative energy.”

In another botanica a few blocks away, Milagro Montero, 61, runs a bright and airy shop with life-sized statues flanking the doorway: Jesus, Mary, Joseph, and angels. She’s hesitant to talk to an outsider, but finally, after several visits, she opens up.

In another botanica a few blocks away, Milagro Montero, 61, runs a bright and airy shop with life-sized statues flanking the doorway: Jesus, Mary, Joseph, and angels. She’s hesitant to talk to an outsider, but finally, after several visits, she opens up.

“I am just one of those people born with a gift,” she said, smiling. “I’ve always had a knack for healing, for cleansing negative energy, for divination.” Her work, she said, runs the gamut from consultations to healing physical ailments with herbs, spiritual cleansings, and card readings. She said clients come to her when medical doctors can’t find the cause of a problem, when patients can’t afford the medicines the doctor has prescribed, or when they need to talk about an emotional or spiritual problem that no one else seems willing to address.

She ran through the herbal remedies she learned as a young woman growing up in El Salvador. “For kidney problems, for instance, I would tell you to make a tea of palo azul and cola de caballo. For problems with your liver, I would recommend boldo. For bronchial problems, pulmonaria. I would also provide that for a woman who had difficulty carrying a fetus to term,” she said.

According to the literature, which includes Zavaleta’s respected book on the subject, Curandero Conversations, and dozens of herbal web sites, every herb she mentioned was appropriate. Palo azul — blue wood — is tree shavings used to treat kidney inflammations, and cola de caballo is field horsetail or shavegrass used by Western herbalists to eliminate kidney stones and treat infections of the urinary tract. Boldo is an herb used as far back as the Incas to treat the liver, bladder, and urinary tract infections. Pulmonaria, known in English as lungwort, is used to treat bronchial problems from hoarseness to bad coughs and also to strengthen the uterus during pregnancy.

Her favorite work, Montero said, is when a woman who cannot have children comes to her for help and subsequently gets pregnant. “I have a special tea that I make with herbs that helps solve that problem,” she said. The ingredients? She laughed — that one was secret.

Her favorite work, Montero said, is when a woman who cannot have children comes to her for help and subsequently gets pregnant. “I have a special tea that I make with herbs that helps solve that problem,” she said. The ingredients? She laughed — that one was secret.

“But I often also give the woman some herbs to give to her husband as well,” she added. “I tell them it’s to balance the energy of the tea. Really it is something for the husband because they are often the reason why their wives can’t get pregnant. Yohimba tea is wonderful for erectile dysfunction. It’s like liquid Viagra.”

Others come in to buy amulets and charms or to be taught which orations to say to ask for luck with money or love or to find work or avoid la migra — immigration agents. Those things aren’t just superstition, she insisted. “Hispanics have a very strong tradition of praying to saints, asking them to intercede with God on their behalf,” Montero said. “That is not something that goes away when they come to Fort Worth. If someone is putting energy out to get something like a job or to find love, that energy has a real force in this world. And asking someone else to pray on their behalf for the same thing, well, that doubles the force.”

Even in folk healing, new things arise. Bobby Sanchez, who works out of his home just north of Dallas, uses the traditional techniques he saw his curandera grandmother use: reading the Tarot, working with stones, cleansing negative energy. But he has also incorporated some techniques from Native American and South American healers.

“Some traditional curanderos might help you with luck to find a relationship,” he said. “I would rather remove the energy blocks that are preventing you from finding your own luck. And we all have blocks. Unless we eliminate them, it’s very difficult to change how we behave.”

Sanchez’ hybrid form of healing doesn’t surprise Zavaleta. “Curanderismo is a folk tradition, but as the world changes, [the tradition] changes as well,” he said. “It’s healthy that American and new age aspects would be included. If that’s what your clients relate to, that’s what’s important.”

There’s at least one medical doctor in town who supports the work of curanderas like Montero and Vargas. Dr. Carlos Reyes-Ortiz, an associate professor at the University of North Texas Health Science Center, said the Hispanic population here is underserved by traditional U.S. healthcare system. Curanderas, he said, are a legitimate alternative to Western medical care for several reasons.

There’s at least one medical doctor in town who supports the work of curanderas like Montero and Vargas. Dr. Carlos Reyes-Ortiz, an associate professor at the University of North Texas Health Science Center, said the Hispanic population here is underserved by traditional U.S. healthcare system. Curanderas, he said, are a legitimate alternative to Western medical care for several reasons.

“You need to remember that among rural Hispanics, there is a belief that physical illness is spiritual in origin,” he said. “Too, those populations are somewhat marginalized, and so have a need for a social safety net — which is something the curandero provides in the way of emotional and mental problems.

“Curanderos who know herbs, for instance, can heal as well as doctors with medicines,” he said. “And curanderos also generally share similar cultural values with their patients that medical doctors rarely do, so curanderos develop a more empathic relationship with their patients than we find in Western medicine.”

That closeness, he believes, breeds belief in the work the curandero is doing, whether the work is physical, emotional, or spiritual. And believing you can get well, he says, is part of the process of getting well.

That closeness, he believes, breeds belief in the work the curandero is doing, whether the work is physical, emotional, or spiritual. And believing you can get well, he says, is part of the process of getting well.

Unfortunately, most Western doctors dismiss folk-healing traditions, often to the detriment of their patients, Reyes-Ortiz said. “Our role should not be to go against that relationship people have with their curanderos — we should instead try to understand the importance of those healers to those patients.”

Zavaleta, the UT-Brownsville professor, didn’t grow up in a family that went to curanderos. “In fact, as a trained anthropologist and scientist, I’m a skeptic,” he said. “But as a young boy I spent a considerable amount of time on my grandparents’ ranch where seasonal workers came through to pick cotton. I would spend days at a time in their camps out in the fields, and that is where I heard the stories of curanderos and of El Niño Fidencio, a legendary and very real healer in Mexico.”

Since then, he said, “I’ve become a believer. Why? Because I’ve simply seen too many miraculous healings to deny them.”

Since then, he said, “I’ve become a believer. Why? Because I’ve simply seen too many miraculous healings to deny them.”

A curandera working with herbs is using the same raw materials as a physician who prescribes medicines, he said. “A family doctor knows probably 100 diseases and as many medicines. Someone who works with herbs can treat those same problems and conditions. It’s how they were all treated before medicines were isolated from those herbs.”

Texas, he said, is particularly fascinating because of the history of the Mexican population here, which Zavaleta describes as a transnational population that shifts back and forth between the U.S. and Mexico, carrying their traditions with them while on this side of the border and reinforcing them when they return to Mexico.

Vargas describes her work, in part, as therapy — hunting down the sources of negative energy that affect her clients. And that can include folks who believe they have been the victim of brujeria — witchcraft performed by a brujo or bruja, the names given to curanderos who have fallen off the path of healing and are willing to do evil for money.

“While brujeria exists in Fort Worth, very few people are affected by it,” she said. “But if they believe they are, then it will affect them. With those people I need to first get them to realize they are not victims, and then I’ve got to find out what is really causing their problems. Maybe they’re having family problems because they’re not communicating or job problems because they are letting family issues get in the way of their work.”

A bigger problem than brujeria are people who pretend to be curanderos to play on clients’ fears, she said. Vargas described one man who tells his clients that he can see bad things coming in their lives and that only he has the power to prevent those things from happening.

“He might tell someone he sees them with cancer in six months, but that he can prevent it for $3,500 or $6,000. And if the client says he doesn’t have that kind of money, he will say, ‘Then you will suffer from the cancer. I can’t help you if you won’t help yourself.’ And then he might tell them to sell their car or take a loan to raise the money, and when the client says he can’t, he’ll say, ‘Which is better, to have a car while you are dying of a horrible disease or to not have a car but to have your health and be able to work to get a new one?’

“He might tell someone he sees them with cancer in six months, but that he can prevent it for $3,500 or $6,000. And if the client says he doesn’t have that kind of money, he will say, ‘Then you will suffer from the cancer. I can’t help you if you won’t help yourself.’ And then he might tell them to sell their car or take a loan to raise the money, and when the client says he can’t, he’ll say, ‘Which is better, to have a car while you are dying of a horrible disease or to not have a car but to have your health and be able to work to get a new one?’

“A lot of people get bullied by their fear, and that bad curandero knows just how to terrify his clients,” she said. “He gives all of us doing the best we can a black mark in the community.”

Zavaleta concurred. “Not everyone who claims to be a curandero has any ability to heal people at all,” he said. “And even among those who have some ability, few have a real gift. Let’s face it: There are an awful lot of parlor tricksters out there.”

On the other side of the coin, non-Hispanics might look at the charms and candles, the beads and images for sale in a botanica and be scared away. “They might even think it evil or satanic,” he said, “because what we don’t know, we fear.”

On the other side of the coin, non-Hispanics might look at the charms and candles, the beads and images for sale in a botanica and be scared away. “They might even think it evil or satanic,” he said, “because what we don’t know, we fear.”

In Mexico or Central America, “vast numbers of people at least occasionally utilize the services of folk healing traditions, even in this day and age,” Zavaleta said. And in places like Fort Worth, “We are certainly talking about a subculture that is vital to that culture but essentially unknown to the culture at large.”