Every few months, Edgar Mouton, 76, gets jolted out of sleep in the middle of the night by a loud horn blast. The sound is a warning: One of 14 industrial facilities nearby has belched out too much pollution into the air.

“When it was worse, back in the ’50s and ’60s,” said Mouton, “we had to evacuate.” These days, he and his neighbors are told by safety officials to “shelter in place.” They must stay inside their homes, turn off the air conditioning, and close all the windows.

Mouton lives near the western shore of Lake Charles in southwestern Louisiana, where the landscape is dominated by an oil refinery, petrochemical plants, vinyl factories, and a cement plant. His home is in Mossville, a modest African-American community adjacent to the industrialized town of Westlake. Mossville is a close-knit and polite place, where residents often encounter distant relatives around the corner and families grow fruits and vegetables in their backyards. Mossville’s harvest, however, is tainted. Tests have shown that residents’ blood carries triple the average national load of dioxin, a toxic known to cause skin lesions, liver problems, and cancer.

Mouton lives near the western shore of Lake Charles in southwestern Louisiana, where the landscape is dominated by an oil refinery, petrochemical plants, vinyl factories, and a cement plant. His home is in Mossville, a modest African-American community adjacent to the industrialized town of Westlake. Mossville is a close-knit and polite place, where residents often encounter distant relatives around the corner and families grow fruits and vegetables in their backyards. Mossville’s harvest, however, is tainted. Tests have shown that residents’ blood carries triple the average national load of dioxin, a toxic known to cause skin lesions, liver problems, and cancer.

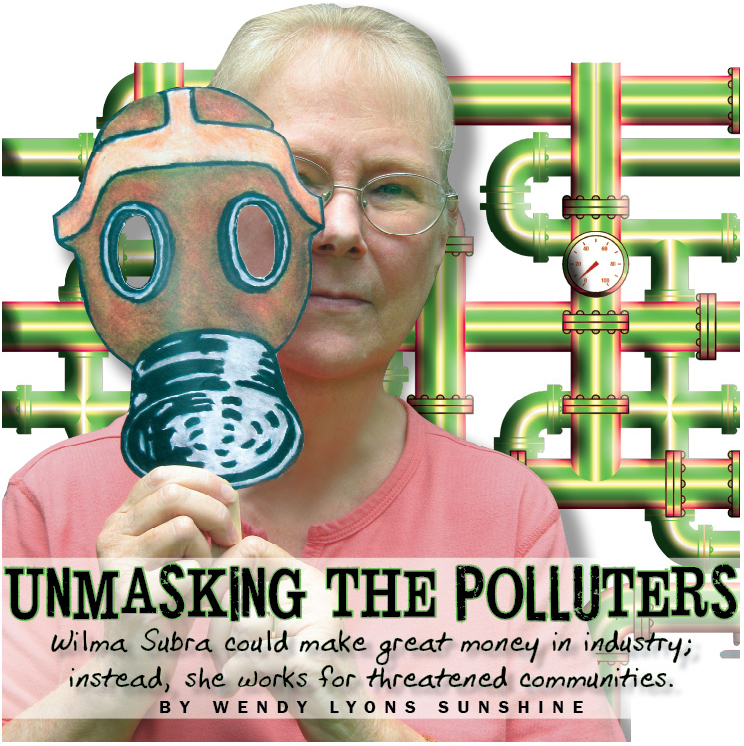

Most families nearest to Westlake’s industrial contamination were relocated in the 1990s. But remaining residents say they have spent decades battling noxious odors, health concerns, and indifferent government agencies. Now, with the help of a scientist named Wilma Subra — a MacArthur “genius” award winner who has assisted communities from North Texas to San Francisco to Pennsylvania — the people of Mossville are hoping to finally achieve environmental justice.

“Wilma Subra has helped us out tremendously,” said Mouton, who serves as president of Mossville Environmental Action Now. “She double-checks the numbers we get from the chemical people. If there have been some numbers that have been mistaken from industry, then Wilma straightens them out.”

“Wilma is a beautiful lady,” said Mossville resident Delma Bennett, 66. “I really think she’s God-sent.”

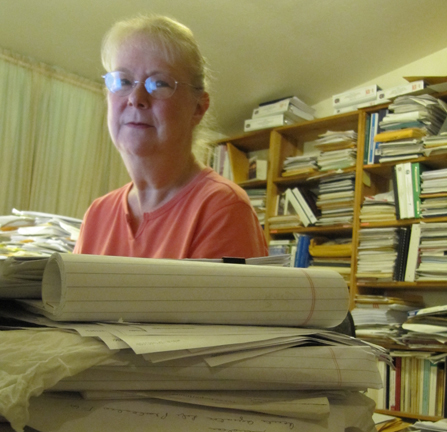

Step inside Subra’s office in New Iberia, 80 miles east of Mossville, and you could swear her greatest talent is burrowing. Every visible surface erupts with stacks of papers and folders. Mountains of files cover the desk and floor; finding a place to walk or sit is a challenge. The wall-to-wall bookcase is crammed full of reference texts.

Subra, 66, specializes in unearthing information about hazardous substances. She can dig into technical reports and piece together the facts that explain why a community is noticing a foul smell in the air, a bad taste in the water, or frequent illness among neighbors. Subra has the rare ability to link obscure scientific details with tangible public health threats and then to explain her findings in plain English. She is willing to pinpoint sources of contamination even when government regulatory agencies can’t — or won’t.

Subra, 66, specializes in unearthing information about hazardous substances. She can dig into technical reports and piece together the facts that explain why a community is noticing a foul smell in the air, a bad taste in the water, or frequent illness among neighbors. Subra has the rare ability to link obscure scientific details with tangible public health threats and then to explain her findings in plain English. She is willing to pinpoint sources of contamination even when government regulatory agencies can’t — or won’t.

Her face is framed by baby-blonde wisps of hair, and she speaks quietly. But don’t be misled. Beneath that mild-mannered demeanor is a laser-sharp mind. It’s 9 a.m. and Subra has already fielded urgent calls from the office of Nancy Pelosi, U.S. Speaker of the House, and others. Now she is explaining the details of an involved environmental case she completed years ago. She rattles off numbers and chemicals and industrial processes that would make most people’s heads spin. Subra’s fierce intelligence is coupled with steely persistence in the face of harassment or resistance.

Her technical skill and determination to assist communities and government agencies alike have taken Subra around the country. She has helped Mossville understand its dioxin risk and aided DISH, Texas, in asking the right questions about Barnett Shale pollution. She’s examined shipyard contamination in San Francisco and lead dust from Chicago smelters. She’s chaired advisory committees for state and federal environmental agencies and testified to Congress about the Deepwater Horizon oil rig disaster. Soon she’ll head to Pennsylvania to review the state’s practices for hydraulic fracturing.

Subra grew up in southern Louisiana, the eldest of six sisters. Her maternal grandfather was a French-speaking oysterman who married a Swiss immigrant. Subra’s father was an accomplished jack-of-all trades: inventor, shipbuilder, and equipment manufacturer. During the summers, Subra helped out in his chemistry lab.

She got her first taste of public service in the mid-1960s while studying microbiology and chemistry at what is now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Townspeople came knocking on the college science department’s doors, worried about the deterioration of the nearby Vermilion River. “Dead cows were floating downstream from rendering plants that discharged their wastes into the river,” said Subra. “Nights and weekends, I’d go out and help people understand what was going on in the river system.”

Subra soon married and moved south to New Iberia, where her husband worked as a medical technologist. After she completed dual masters’ degrees in chemistry and microbiology, Subra took a job at Gulf South Research Institute, where she assisted with studies for the National Cancer Institute and helped develop guidelines and equipment for purposes like wastewater monitoring and toxicology. She spent 14 years there as a chemist, microbiologist, and biostatistician, including a few years leading the analytical biochemistry department.

“The entire time I was there, people would come and ask for help,” said Subra. In her spare time, she visited those communities and helped residents understand the issues so they could make informed decisions about the next steps to protect their health and environment.

While at the institute, Subra often led “quick-response projects” for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. This involved bringing a mobile lab and team out to sample a community’s air and soil and collect residents’ blood and urine for analysis. But the process frustrated her.

“People were a code number. All they received back was a summary of the results,” she said. “You couldn’t go back and visit with them and look at their individual data. You couldn’t say, ‘You have an elevated level of this chemical; you may want to look at where that exposure is coming from.’ There wasn’t anybody working with the community to help them understand.”

In 1981, with three children at home, Subra left the institute and formed a company that provides technical assistance on environmental issues. Her firm occasionally gets assignments from small-business clients concerned about contamination in their products, such as a food manufacturer troubled by mold. But most of Subra’s energy goes toward helping communities and nonprofit organizations. At any given time, she’s got about 40 active projects. Subra turns no one away. “Sometimes they have to wait a day or two, but I’ve never had to tell anybody no,” she said, breaking into a smile.

Subra doesn’t sugarcoat the facts when she finds environmental contamination, and this bluntness sometimes makes people angry. For years she was harassed by regular break-ins at her office; intruders stole incidental items and cut wiring to the alarm. Then a few years ago, in the early evening while her husband happened to be tending flower beds behind the building, someone in a passing car put a bullet through the front window of her office.

It’s doubtful the drive-by was accidental; Subra works inside a former rent house opposite a sugarcane field on a rarely traveled road. The shooting may have been related to one of two contentious cases she was investigating at the time: a landfill in a Vietnamese community in New Orleans and natural gas storage in a salt dome in New Iberia.

After the shooting, Subra hired a security expert. At his suggestion, she moved her desk to the back of the building, shortened office hours, and installed bullet-proof glass on all the windows. Then she kept on working.

After the shooting, Subra hired a security expert. At his suggestion, she moved her desk to the back of the building, shortened office hours, and installed bullet-proof glass on all the windows. Then she kept on working.

But the truth is, she said, “You can’t do this work and not be visible.”

Subra’s commitment and expertise have earned her national recognition. In 1999, she received a prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Fellowship, reserved for exceptionally accomplished individuals. Subra was delighted, because the $370,000 grant subsidized five more years of community assistance.

“Someone with Wilma’s skills and resumé would make a lot of money in the private sector,” said Marylee Orr of the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN) and Mississippi River Keepers. She has worked closely with Subra for more than 15 years. “But Wilma is very giving, and this work isn’t about money for her. It’s about helping people.”

Since April, when the Deepwater Horizon rig sank in the Gulf of Mexico and triggered the largest oil spill in U.S. history, Orr and Subra have talked by phone every day, often many times a day, working to address the catastrophe’s environmental impacts. They’ve examined air quality, assessed worker health and safety, given interviews to the press, and shared concerns with regulatory agencies. Subra has assisted the EPA during a string of White House administrations; Dr. Al Armendariz, current EPA Region 6 administrator, confirmed that the agency has a “long successful history of working with Ms. Subra to address important environmental challenges.”

Over the past few months, as oil from the Deepwater catastrophe moved farther along the Louisiana coast, Subra has served as a point person for the EPA, letting the agency know where people in her area are being affected and suggesting places around Grand Isle to place monitoring stations. She sought help from OSHA for the fishermen-turned-cleanup-workers and has fielded all kinds of spill-related requests. Subra even guided Hollywood celebrities around Grand Isle when they came to film a documentary on the spill.

Over the past few months, as oil from the Deepwater catastrophe moved farther along the Louisiana coast, Subra has served as a point person for the EPA, letting the agency know where people in her area are being affected and suggesting places around Grand Isle to place monitoring stations. She sought help from OSHA for the fishermen-turned-cleanup-workers and has fielded all kinds of spill-related requests. Subra even guided Hollywood celebrities around Grand Isle when they came to film a documentary on the spill.

In June she testified before the U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee when members wanted to learn close-up about the impact of the Deepwater spill. They listened to Subra describe how people in New Orleans and along the coast were suffering headaches, nausea, asthma, and other ailments due to tiny particles of crude oil suspended in the air. She told lawmakers that “workers, including the fishermen, were reluctant to report their health symptoms for fear they would lose their jobs … [and] wives stopped speaking out for fear their husbands would lose their jobs.”

Subra recounted how British Petroleum failed to honor its agreement to properly train the crews working on clean-up boats. LEAN had provided many of the fishermen with protective gear, but Subra explained that “fishermen who attempted to wear respirators while working were threatened to be fired by BP.” On behalf of LEAN, she implored Congress to enforce existing laws and regulations to protect the coastal community.

“This is really very difficult work,” said Orr, about the challenges facing anyone who hopes to protect communities and the environment. “It’s physically draining, emotionally draining, and psychologically draining; it can take you away from your family. The financial resources are not the same as if you’re in the corporate world. Wilma has paid a certain price for trying to make change, but she is very good at empowering people.

“I can’t say enough good things about Wilma,” the LEAN leader said. “She’s an angel; she appears just when you need her.”

In 2008, gas drilling crews were disrupting neighborhoods and rural areas across North Texas. Sharon Wilson and other residents sought help from the national Oil and Gas Accountability Project. In October of that year, the group’s leadership visited Texas. They brought Subra along.

“Everyone was in complete awe of Wilma, her knowledge, and what she has done. You can ask her almost any question about the oil and gas industry, and she can answer it,” said Wilson, known for her “BlueDaze” blog.

In February of this year, OGAP launched a Texas branch. Wilson, who serves as its spokeswoman, credits Subra with deepening her knowledge about gas drilling.

Wilson, for example, learned that “produced water,” a byproduct of the drilling process, is not simply salt water. In addition to a lot of salt, it contains oil and grease, chemical additives, and naturally occurring radioactive material. It can contain radium 226 or 228, — radioactive substances with a half-life of 1,620 years. When produced water leaks, spills, or is dumped, it kills plants and trees and can contaminate the soil, groundwater, and surface water.

Texas OGAP released a short document, called Drill-Right Texas, which calls for “responsible energy development that protects private property owners, water, the environment, and public lands while enabling energy production.” The document outlines ideal industry practices, such as setting back wells at least 1,000 feet from residential areas and capturing hazardous vapors that escape from condensate tanks.

With Subra as a technical advisor, Wilson tracks Barnett Shale concerns, posts updates to her blog, attends city council meetings and agency hearings, and urges government agencies to do more to protect public health and safety. At the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality meeting about ozone pollution in June, she distributed cutout paper “gas masks,” which attendees could hold over their faces to show their skepticism about statements made by TCEQ representatives.

At an EPA public meeting in July, Wilson voiced concern about gas company claims that hydraulic fracturing of wells is a precise science, because internal industry documents suggest the opposite. As an example, she provided the EPA with a 2010 Canadian Oil and Gas Commission safety advisory that says it’s hard to anticipate exactly how far engineered cracks in a shale formation will spread underground.

“I rely on Wilma a great deal; I can call her up anytime,” said Wilson. “She has been a tremendous support. She is an amazing person. I have never seen anyone, young or old, with as much energy as she has. She just runs me into the ground. I am in awe of her.”

DISH sits squarely on the pulse of the Barnett Shale, North Texas’ vast natural gas “play.” A map at the DISH town hall shows a tangle of gas pipelines crisscrossing the 200-person community. Mayor Calvin Tillman said the map is already out of date; more pipelines and wells have been added since it was published. He points to places where various industry players set up shop just outside of town limits; he believes that was to avoid stricter ordinances.

DISH sits squarely on the pulse of the Barnett Shale, North Texas’ vast natural gas “play.” A map at the DISH town hall shows a tangle of gas pipelines crisscrossing the 200-person community. Mayor Calvin Tillman said the map is already out of date; more pipelines and wells have been added since it was published. He points to places where various industry players set up shop just outside of town limits; he believes that was to avoid stricter ordinances.

By the time Tillman became mayor in 2007, DISH residents had begun worrying about how their once-quiet town was being disrupted by the gas facilities. “Relief valves would go off in the middle of the night, and it was loud, like jet engine sounds,” said Tillman. “Odors would fill my house. My kids would wake up in the middle of the night with nosebleeds.” When state and federal agencies did not address the town’s concerns sufficiently, DISH took money from its budget and paid an independent firm to test the air.

“Wilma helped us identify what to test for,” said Tillman, who served on the Texas OGAP steering committee. She also designed a health questionnaire for the mayor to distribute to town residents, and after he collected their responses, Subra made sense of all the findings. She explained how the air-emission test results linked to residents’ health complaints. “It’s been good to have an unbiased opinion on the way things are here,” the mayor said.

In March, Subra invited a California company, Picarro, out to North Texas to test-drive its new state-of-the-art mobile pollution detection equipment. Called a “cavity ringdown spectrometer” — incorporating lasers, infrared light, and world-class mirrors — the instrument can detect methane and hydrogen sulfide in real time from a moving vehicle and map three-dimensional results using GPS.

Subra, Wilson, and others climbed into a van with Picarro scientist Chris Rella and went hunting for Barnett Shale methane spikes. Rella compares the outing to storm chasing, “only for gas plumes.”

The team drove past compressor stations and other industrial facilities in DISH and elsewhere; they detected the largest spikes in Flower Mound and Fort Worth. At the gas plumes, Subra stopped the van and stepped out to sample air with canisters for further lab analysis. If methane, the primary component of natural gas, is present in high levels, it means that volatile organic compounds are likely present too. These compounds, commonly called VOCs, include benzene, toluene, and other cancer-causing chemicals.

Tillman talks about relocating his family away from DISH and the Barnett Shale, but he hasn’t put his house up for sale yet and admits that lately he has seen definite improvement. He said industry operators have fixed leaky equipment in DISH and strategically moved relief valves away from residential areas.

In April TCEQ installed an automatic gas chromatograph (or “AutoGC”) air-monitoring station in town. It operates around the clock, testing for 46 chemicals at a cost to the state of $250,000 for the first year and $100,000 a year thereafter. Results are published on TCEQ’s compliance web site with a four-hour delay.

During my visit, the mayor drove us to see gas industry landmarks near the center of DISH. We swung by a completed pad site surrounded by masonry walls, a pond of clean water reserved for fraccing, compressors near a small airport, and a horse stable and residential development that sit next to gas facilities.

We looked at the TCEQ air monitor, which resembles a small trailer with a large antenna. “There’s a problem here, or they wouldn’t have spent a quarter-million dollars on this piece of equipment,” Tillman said, pointing to the monitor. “That thing is by far the best thing TCEQ has done for us.” He looked around, sniffed the air, and remarked on how much better the area smelled compared to a year earlier.

“I get more and more optimistic,” he said. “Things are getting so much better, but you have to stay on top of this.”

“So many agencies say, ‘It’s not an issue, it’s not a problem,’ ” said Subra. “So you have to keep making the point that it is an issue, it is a problem.” She’s talking about the cumulative effects of unrestrained industrial permitting, and she is worried.

In Texas, a policy called “Permit By Rule” (PBR) allows a company to fill out an application and relatively easily get clearance to operate a gas compressor that releases up to 250 tons per year of greenhouse gases or 25 tons per year of VOCs, particulate matter (such as soot, which is linked to respiratory problems and heart disease), sulfur dioxide, or other contaminants. Subra explained that as more and more equipment gets permitted, toxic emissions add up, and the overall health risk rises. TCEQ spokesman Terry Clawson said by e-mail that there is no limit on the total number of compressor permits allowed by the state, and his agency approves 95 percent of all applications.

TCEQ has made some strides. After prodding by the public, TCEQ has collected and posted details about equipment, such as compressor engines, used in the Barnett Shale. According to data for 2009, Tarrant and Johnson counties alone hosted more than 6,425 devices that are recognized as potential sources of hazardous air pollution. In addition, Johnson County had 3,855 storage tanks for the industrial waste known as produced water.

TCEQ plans to collect and post an inventory of air pollution coming from Barnett Shale equipment. Thus far the state has not required companies to employ “green” well-closure methods or install hazardous-vapor recovery devices. But TCEQ is paying closer attention. The agency has installed the DISH air monitor and one near Eagle Mountain Lake and plans three more for the Barnett Shale area “in the near future,” said Clawson. TCEQ has also assigned seven more environmental investigators to the DFW region.

Earlier this month, the Barnett Shale Energy Education Council released an industry-funded study examining air quality at two compressor stations and eight of the 2,398 active gas wells in Tarrant County. A Fort Worth Star-Telegram article quoted Arlington Mayor Dr. Robert Cluck as calling the results “really good news.” The Weekly asked Subra to review the study and give her opinion.

“I do not agree that the results are really good,” said Subra by e-mail. She found the study flawed because it ignored active drill sites, did not include methane volume or sulfur compounds, and overlooked cumulative effects. The study was too incomplete to be reassuring.

For example, the most polluted test site (the Encana Mercer Ranch wet gas well site) released 32 toxic chemicals during short-term and long-term testing. Although each of the toxic substances by itself was detected at below government health standard levels, their combined presence increases risk. The more toxic chemicals in one place, the more danger, said Subra. “If cumulative impacts are not considered, the potential for health impacts is missed.”

![Wilson: “I am in awe of her [Subra].” feat_5](https://www.fwweekly.com/wp-content/images/stories/images/7-28-2010/feat_5.jpg) Cumulative exposure can lead to asthma, allergic conditions, cancer, heart problems, and other illnesses. Industry promoters may defend the study as being patterned after the state’s own air monitoring, but Subra believes that TCEQ’s methods are inadequate too.

Cumulative exposure can lead to asthma, allergic conditions, cancer, heart problems, and other illnesses. Industry promoters may defend the study as being patterned after the state’s own air monitoring, but Subra believes that TCEQ’s methods are inadequate too.

“I am not a proponent of experimental science, but I would be delighted if Wilma Subra could be cloned,” said attorney Monique Harden, co-director of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights, based in New Orleans. “She is an incredible person. Wilma brings a very valuable asset to this dynamic.”

Harden believes that dangers from common industrial operations, such as offshore oil drilling and refineries, are routinely ignored. AEHR represents groups, such as Mossville residents, who are suffering due to flawed regulatory practices and injustices.

AEHR has been working with Mossville to pursue legal remedies for the dioxin contamination. The group has even raised Mossville’s concerns with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an organization dedicated to protecting human rights throughout 35 member countries. AEHR hopes the commission will recommend the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in San José, Costa Rica, for resolution. The materials AEHR submitted for the case are heavily footnoted with references to Wilma Subra.

“You can’t enjoy your human rights if you’re living in a severely damaged environment,” said Harden. “We’re talking [about pollution] so severe that it warrants displacement and relocation of people, folks living in kill zones of toxic industrial facilities. They need someone on their side, making the scientific case that it is dangerous and warrants change.”

Harden said she has never encountered a contaminated community where Subra was not able to make a pivotal contribution. What’s so exceptional, she believes, is that Subra uses companies’ own data to make the case against them.

“You go into these meetings with corporate polluters — where they’re really there to say ‘It’s not a problem’ — and Wilma is able to say, ‘Using your information, information you’ve generated, yes, this is a problem.’ They’re left like deer stuck in the headlights,” said Harden. “They don’t have an answer for that. It’s priceless what Wilma’s able to do. She’s making the case for change.”

It has begun to drizzle in Mossville, so Edgar Mouton and I step out of the Louisiana heat and into my rental car to talk. He describes the 28 years he spent working at one of the nearby chemical complexes, operating and loading trucks at lime, acid, and ammonia plants. For someone with a ninth-grade education who was raising a family, it was a great opportunity. Jobs outside the plants paid half as much. For years, Mouton accepted strong odors as a part of the work; he was rarely advised to wear protective gear.

“When I was working in the plant, I didn’t know how detrimental these plants were,” he says. Then he became a volunteer fireman and was required to take safety classes about chemical fires and burns. Learning about protective gear gave him insight into the dangers. Plus he was showing worrisome symptoms. He had developed asthma and became increasingly sensitive to the chemicals he handled daily. Mouton says his health has improved since he retired, although I notice he coughs periodically.

Delma Bennett, 66, arrives and joins us in the car. After graduating from high school and spending time in the military, he worked for 10 years in one of the local synthetic rubber and latex plants. Like other members of the local environmental group, he believes that Mossville was treated shabbily because of racial discrimination.

A report prepared by Subra and AEHR about dioxin poisoning in Mossville — based on the government’s own data — helps explain the community’s frustration. In 1998 the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry collected blood from 28 volunteers in Mossville and tested it for dioxin. Results showed levels triple the average U.S. rate — higher, in fact, than 95 percent of the population. Yet mysteriously, ATSDR’s sole response was to take a follow-up blood test of 22 residents in 2001.

Another five years passed before ATSDR announced results of its follow-up tests, which revealed dioxin levels barely lower than the first reading. The report described contamination in fish from local waters, in soil from residents’ yards and dust from inside their homes, and in the vegetables and fruit they’d grown. Despite that, ATSDR concluded that “the health significance of the blood dioxin concentrations measured in this investigation is unclear.”

Mossville residents and Subra can’t understand ATSD’s inaction, particularly since the agency’s published mission is “to assess the presence and nature of health hazards” and “to help reduce further exposures.”

Dr. Sanjay Gupta of CNN explored the connection between contamination and illness on his CNN “Toxic Town” television special earlier this year. He spoke on camera with a roomful of Mossville residents who recounted how high levels of cancer and other illnesses plague their families. Gupta also gave substantial air time to Subra and Dorothy Felix, vice president of MEAN.

Now the community is waiting to learn whether EPA will designate Mossville as a Superfund site. In the summer of 2009, the EPA visited and took samples of tap water. In spring 2010, they collected soil and other evidence for tests. The agency promised results this month, but there’s been a glitch.

EPA spokesman Dave Bary explained to the Weekly by e-mail that documentation for the spring soil and water samples was “suspect,” so the agency will redo the tests in mid-August. He expects the analysis to be completed around October. After the agency gives results to individuals in Mossville, he said, “perhaps we will be able to discuss the results in general terms.”

Two young women who are members of the local environmental group pull up in a car next to us. The rain has eased, so I suggest we go get a photo of them by one of the industrial plants. Bennett says it won’t be easy. Ever since the CNN story, local security and public safety officials have become extra vigilant.

A few weeks earlier, while showing reporters around outside the ConocoPhillips refinery, he was detained for three hours, Bennett said. Plant security, the sheriff, the police, Homeland Security, and the FBI all questioned him separately. Eventually they let him go.

“They are very serious about news reporters or anybody driving up in front of their place taking pictures,” says Mouton.

The men decide our best chance is on the road by the Georgia Gulf plant, opposite an overgrown area where the relocated families used to live. We manage to shoot a few pictures there and climb back into my car. A moment later, a car appears at the plant entry.

I’m nervous as the car heads toward us and mash my foot down on the gas pedal. “Don’t run,” Bennett advises. “If you run, they’ll think you’re doing something wrong.”

We chat briefly with the security guard, and he drives away. Then the MEAN members and I seek refuge in a local church to talk further.

After just two hours in Mossville, I’m wheezing from the acrid air. I can’t wait to get on the road.

The next day, I ask Subra about her own health. “I’m very careful and don’t stay in these areas very long,” she said. “I always get a sore throat and headache if I go where there is sulfur crude or sour crude.” As a precaution, Subra keeps strong filters on the ventilation systems at her office and home and eats organic food when it’s available.

Amid the piles of reports and papers cramming her office, Subra keeps one alcove tidy. It’s equipped with a couch, TV, dollhouse, and stuffed animals for grandchildren who sometimes stay during the day. Photos line a nearby desk. “Family is very important,” says Subra. “I try to have as much time available as I can for my children and grandchildren.”

We step into the rear yard, and Subra points out the tall bamboo plants that help shelter local homes from storms. Her youngest grandson was born during Hurricane Ike. “We were on the edge of impact from Katrina,” she says, “but had the full force of Rita.”

Why would Subra continue to live in a tropical storm zone? “This is a great place,” she says. “There’s always going to be something — tornadoes in other areas or ice storms. If you prepare for the hurricanes, you’ll be OK.” She and her husband built their home to last, with its roof anchored to the sidewalls. They keep a power generator on hand and don’t evacuate.

Subra doesn’t mind battling fierce winds; she simply prepares.

Wendy Lyons Sunshine is a freelance writer who has written for ScientificAmerican.com.