When Fort Worth voters passed a bond package in 2004, it included funds for a community recreation center in North Fort Worth. Lance Griggs, president of the Summerfields Neighborhood Association, thought that the community center — which was to offer a public pool — would be built at Summerbrook Park.

But the city changed course and instead used that bond money to pay half the $5 million cost of the new Northpark YMCA facility on North Beach Street. Griggs and other leaders from the Far North Side have now asked the Texas attorney general’s office to rule on whether that action violated state law.

But the city changed course and instead used that bond money to pay half the $5 million cost of the new Northpark YMCA facility on North Beach Street. Griggs and other leaders from the Far North Side have now asked the Texas attorney general’s office to rule on whether that action violated state law.

The city is allowed to do “partnerships” with government and private entities — that’s the official explanation for why it used public bond money to help build the YMCA facility, which for the most part can only be used by those who pay YMCA membership fees.

“This is obviously a misappropriation of funding, and we aren’t going to put up with it,” Griggs said. “We have a real need for community centers in this city, better parks, pools where kids can swim during the summer, and we get the city subsidizing what is basically a private athletic facility. We don’t think that is a proper use of our tax dollars.”

But the denial of the community center and funding of the YMCA facility isn’t the only thing that upsets Griggs and others. The city closed six of its seven pools this summer because of budget shortfalls and contracted with four YMCA locations to open their pools to Fort Worth residents for a decreased fee for a few hours each afternoon. But the new Northpark YMCA wasn’t part of that.

The city and the local YMCA reasoned that Northpark would be too crowded with dues-paying members to justify opening it to nonmembers — even though those nonmembers’ tax dollars helped pay for it.

“So we pay for this private facility, and we can’t even use it,” said Griggs, a retired Lockheed Martin program manager. “A lot of people think we’re all rich up here in North Fort Worth, and we all live in mansions with pools. But there are a lot of a older homes here, a diverse income base, and apartment complexes that don’t have pools.”

City spokesperson Veronica Villegas said the decision to partner with the YMCA was based on an assessment of needs for North Fort Worth residents. “What the residents told us was that they wanted a facility with aquatics and a fitness center, and a community center would not address the fitness aspect,” she said. “So the partnership allowed us to meet the needs and stay within budget.”

“The Y and the city both are nonprofits and provide services for the general public,” Villegas said. “We discovered that the monthly fees at the Y … were about the same as [what] people would pay [for] the same programs at a community center.”

“The Y and the city both are nonprofits and provide services for the general public,” Villegas said. “We discovered that the monthly fees at the Y … were about the same as [what] people would pay [for] the same programs at a community center.”

Griggs disagrees. “They are saying to families that they can swim in the summer if they pay about $700 a year to the YMCA,” he said. “But we all pay taxes, and the city seems to think basic city services like good parks and recreation centers and swimming pools aren’t really that important.”

That same sentiment seems to be echoing in many areas of Cowtown. The closing of the pools has exacerbated those feelings, but there are larger issues at play. The population of the city is growing fast, but some feel that the city is not doing much to keep up with the resulting need for more parks. And with the budget problems, maintenance of existing parks is also being squeezed.

Add to that the cuts in services at 22 community centers — such as after-school programs for kids, late-night programs that keep kids off the streets, and educational and health programs for seniors — and the situation gets even worse. Cuts made last year will undoubtedly go deeper this year, with an even larger deficit looming.

At issue is what city parks and recreation programs mean to the overall vitality of a large city like Fort Worth. A strong park system is a good indicator of quality of life, and employers and workers make decisions about where to set up businesses or take jobs based on attractive open spaces and recreational opportunities.

In a survey done by the city last year, a good park system was rated as the most important “community investment” among Fort Worth citizens, ranking even higher than better roads. Of those who responded, 77 percent were either “very supportive” or “somewhat supportive” of renovating and adding facilities to the park system. New indoor and outdoor aquatic facilities received support from 64 percent of respondents.

Study after study also indicates that property values — and thus property taxes — are much higher for homes and businesses within a mile of a park. The resulting tax dollars go into the city’s general fund, which can offset the cost of other services like police and fire protection.

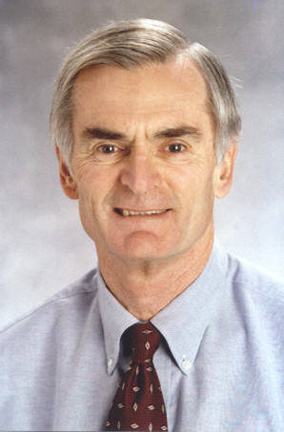

John L. Crompton, a professor of parks and tourism sciences at Texas A&M University, warns that local governments that focus budget cuts on park systems are making a major policy error. “If the parks system declines, the property values decline, and businesses might not want to locate there,” he said. “So what you think you are saving in present-day spending, you will be losing more in future revenue.”

Crompton lectures around the world, and he asks his audiences which city they’d most love to live in and why. “More than 80 percent cite good parks and recreation and environmental ambience,” he said. “So good parks are like a canary in a coal mine for cities. Most people think that a city that doesn’t do parks very well probably doesn’t do most other things well. The city is perceived as not functioning.”

Griggs agrees with that perception. “There are a lot of people who move up to this part of Fort Worth from other parts of the country, and most all of them have the same question: Why are there hardly any parks here, and why do most of them have little more than swing sets? I have a hard time answering that question.”

It is difficult to compare park systems among various cities. You can’t measure Central Park in New York City against the Trinity Trails system in Fort Worth or equate Presidio Park near the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco with the beaches along Lake Michigan in Chicago.

But the Trust for Public Land, a nonprofit based in San Francisco, makes an attempt. The trust works with local governments in acquiring park property and planning its use. The group also does annual surveys of 77 large cities, comparing the total amount of parkland, spending on the park system, and park payrolls.

But the Trust for Public Land, a nonprofit based in San Francisco, makes an attempt. The trust works with local governments in acquiring park property and planning its use. The group also does annual surveys of 77 large cities, comparing the total amount of parkland, spending on the park system, and park payrolls.

In the most recent data, from 2008, Fort Worth ranks quite low in all categories.

Fort Worth has about 11,000 acres of parkland, or about six percent of the total area. That may seem high, but compared to other large cities it’s not — the average is 10 percent. Per capita numbers are even worse. Fort Worth has 16 acres of park property per 1,000 residents; the national average is 40. For “low-density” cities like Fort Worth, the average is 102 acres.

Maybe we make exceptionally good use and take really good care of what we have? Nah. The national average for total park spending is $100 per resident per year, while Fort Worth shells out only $62. Fort Worth spends $47 on park maintenance each year per resident, while the average city spends $71. On capital expenditures — meaning acquiring new park property and installing new equipment — Fort Worth comes in at about half the national average, $15 per resident versus $28 annually.

And compared to other big cities in Texas, Fort Worth’s ranking slides further. Cowtown ranks near the bottom in all categories.

“Budget shortfalls are happening in just about every city, and some cities don’t see parks as an essential service like police and fire,” said Ben Welle, who oversees the survey for the Trust for Public Land. “But residents of those cities must make it clear to their politicians that parks and recreation programs are essential.

“When it comes to budget cuts, libraries and parks always seem to get the short end of the stick,” he said.

Cities that already lag on park funding are likely to fall much further behind when they start having to make budget cuts, he said.

“Cities like Minneapolis and Seattle will cut their parks budget, but there won’t be a big drop-off because they have spent a lot of money in the past,” he said. “But a city that doesn’t have adequate funding to begin with, and cuts its budget substantially, will be playing catch-up for a long time, and that will have a lasting impact on their neighborhoods.”

“Cities like Minneapolis and Seattle will cut their parks budget, but there won’t be a big drop-off because they have spent a lot of money in the past,” he said. “But a city that doesn’t have adequate funding to begin with, and cuts its budget substantially, will be playing catch-up for a long time, and that will have a lasting impact on their neighborhoods.”

Fort Worth increased its parks and recreation budget from $28 million in 2007 to $36 million in 2009. This year, the budget was cut to $33 million, and another $3 million is likely to be cut in September, when a new budget is due to be approved.

“All [city] departments have been directed to submit budget-reduction scenarios of 10 percent (public safety department five percent),” Fort Worth Parks and Community Services Director Richard Zavala wrote in an e-mail. “All programs and operations are given consideration.” He would not agree to a face-to-face interview with the Weekly.

“From a quality-of-life perspective, the reduction of park and recreation programs will negatively affect users,” Zavala continued. “However, in this very depressed economy, it is government’s responsibility to maintain core services, i.e. police, fire, garbage.”

In some areas, residents say the city’s neglect of parks has produced a self-fulfilling prophecy: Less maintenance and fewer improvements in parks mean there’s less for kids to do — and therefore less reason for families to come to the parks, which increases the likelihood of crime, which drives the families away even more.

Mary Blakemore, president of the New and Improved Hillside Neighborhood Association, on the city’s East Side along Rosedale Avenue, has been fighting with the city for years about getting park improvements in her area. The 24-acre Hillside Park has only some playground equipment and picnic tables to attract kids. There’s also a pool, but it’s closed.

“We used to have the pool, and they took that away,” Blakemore said. “We asked for a walking trail, and the city has ignored us. This could be a beautiful park, with places for kids to run and play, to swim during the hot summer, and all they give us is some picnic tables.

“Kids need an outlet, for their health and for safety reasons for the whole neighborhood,” she said. “As these parks are left to deteriorate, they become havens for gangs and crime activity. We have asked the city for better lighting at Hillside Park, and they don’t listen to us. So we have a park that people don’t use much, because basically all you can do is picnic. And that opens it up for serious safety issues for our neighborhood.”

One city park that has had serious crime issues is Cobb Park on the city’s East Side. At 152 acres, Cobb is one of the city’s largest, but in recent years there have been murders, corpses found, and two rapes. The city has a plan to invest $25 million in new trails, baseball fields, and basketball courts. Construction was to begin last year, but the project has been delayed by the budget problems.

“Cobb Park is close to our neighborhood, but no one wants to go there, given the safety issues,” Blakemore said. “Cobb is big and should be utilized more. But it is a perfect example of how a lack of park maintenance leads directly to crime and safety issues.”

Fort Worth Police Officer Chris Munday, the neighborhood patrol officer for the city’s central district, which includes Cobb, said crime at the big park has gone down in recent years because of increased patrols. “But I agree that maintenance like better lighting and better facilities increases park usage and will provide better safety for citizens using the parks,” he said.

Eastside activist Phyllis Allen puts the blame for pool closings, recreation center cutbacks, and park deterioration squarely at the feet of Mayor Mike Moncrief. “I have lived in the city my whole life, and I have never seen the city staff and council work so much in dark backroom deals that keep the public out of the discussion,” she said.

“I had worked with Moncrief when he was a state senator, and I was very impressed with his sympathy and compassion for the underprivileged,” Allen said. “I was so excited when he ran for mayor, but he has changed completely. He seems to be only taking care of the wealthy and attractive people.”

“I had worked with Moncrief when he was a state senator, and I was very impressed with his sympathy and compassion for the underprivileged,” Allen said. “I was so excited when he ran for mayor, but he has changed completely. He seems to be only taking care of the wealthy and attractive people.”

Allen has worked tirelessly against the city’s plan to make Riverside Park the flood pool for the Trinity River Vision project. The city’s plan would add acreage and equipment to Riverside Park, but about 30 acres would be dug out to a much lower level and would probably flood a few times a year. Some residents worry about the toxic environmental mess that could result.

“The folks on the West Side didn’t want the flood-control project near their country clubs, so the city moved it on us,” Allen said. “We have had public meeting after public meeting, and the residents have said repeatedly that we want Riverside Park improved, but not at the cost of us bearing the burden of flooding.

“The city staff doesn’t communicate with us, and they seem to have already made up their minds on what they plan to do,” she said. “Parks and pools and community centers are not a charity for the people. We pay our taxes like everyone else, but they are taking away things that improve our quality of life, one at a time. I don’t see that happening in other parts of town.”

Some might wonder why the city would close pools but keep its five golf courses open. The reason, according to city staffers, is that the golf courses are self-supporting: Greens fees, cart rentals, and food service pay for the staffing and maintenance. Pool usage fees, on the other hand, don’t cover pool maintenance and staffing costs.

In that case, some residents argued, why not increase pool fees to cover costs and allow them to remain open. According to a former parks board member, staffers made it clear that the city wants to get out of the pool business, and the higher-fee option wasn’t even considered.

If neighborhood leaders are hot over hidden agendas and lack of attention to public input, some Parks and Community Services board members, current and past, feel the same way — though certainly not all. Some board members say they frequently find out about agenda items only a few days before the meeting at which they are expected to vote on them, and they often do not have a clear understanding of what they are being asked to approve.

“It is no great secret that I had gotten mad at the city staff,” said board member James Nuttall, a land manager for a natural gas company. “We get items a few days before the meeting, and then the staff presents what they want to us to do and manage the outcome they want.”

Nuttall also said public hearings need to be held for bigger issues, like the closing of pools. “We need to get better input from citizens, but because they give us just a few days to review items before a vote, there is little time to get any input,” he said.

Board member Glen Estes disagreed. “Overall, [the timing of] when the advisory board gets the agenda or agenda items has not been a problem,” he said. “Most action items were presented in considerable detail as information items the month before.”

But former board member Debra Nyul said the board was ambushed in some ways over the closing of the city pools. For two years, the city staff presented plans to close the pools, and the board rejected them each time. Then last year, with the budget cuts, the board acquiesced to the recommendation to close the pools, saving the city about $450,000.

“When we were deciding on the budget cuts, we prioritized what was important for the city and some things that weren’t,” Nyul said. “Pool closings were at the bottom of our list [of programs to cut], but Mr. Zavala put the pool closings at number three. And the board decided to go along with city staff on that.”

Nyul said the board was under the impression that the six closed pools would reopen once the budget situation improved. But last September, the board was informed that the pools were slated for demolition.

“That was the first we heard about that, and we were told it was in the city’s master plan,” she said. “And we were told that only after one of the board members asked if they were being demolished.” Nyul said the pool demolition was inserted in the city’s master plan without the parks board approval.

The plan — at least the staff’s plan — now is to consider investing in cheaper “splash pads,” areas with spray stations. The spray parks are part of the city’s Aquatics Master Plan, but no timetable has been set on when they might be built.

“The idea of reopening the city swimming pools is a bit like doing a major overhaul on a 30-year-old Commodore 64 computer,” Estes said. “All the swimming pools are way beyond their expected lifetime usage and are incredibly expensive to operate. Based on the cost per person [of those] who use the pools, this is by far the most costly service the parks department provides. It is so costly that it takes money away from providing other much-needed services.”

But many wonder why the budget cuts are needed with all the Barnett Shale income from gas drilling under city-owned park property. The reasons are complicated, made more so by city spending policies.

As of March, the city had received about $30 million from drilling under park properties. Because the city receives some federal funding for its parks, federal rules require that some of the money be spent in those parks — but for capital improvements, not for maintenance. Fort Worth has also imposed its own limitations, requiring that half of that money be put in an endowment, where the capital cannot be touched.

Thus far the city has spent about $14 million of the $30 million, mostly on things like new playground equipment.

Nyul said the parks board has no real influence on the gas revenue spending policy but that it does approve where and when drilling occurs in and around park property. “It was frustrating, because we were always put in a rush to make decisions on gas wells and pipelines,” she said. “But we were not allowed to hear anything about high-impact wells and their impact on parks.”

She said some parks staffers have told her privately that they are frustrated at having to spend “too much of their time on gas-drilling issues, rather than on parks development and maintenance. I’m not sure that’s the best use of the staff.

She said some parks staffers have told her privately that they are frustrated at having to spend “too much of their time on gas-drilling issues, rather than on parks development and maintenance. I’m not sure that’s the best use of the staff.

“And making it more frustrating is the limits the city puts on how that money can be spent,” Nyul said. “If we have to put up with pipelines running through our parks, at least we ought to be able to use that money so that we don’t have to cut essential city services.”

One decision made by the city about gas wells could have an impact on acquiring more park property, but even that is up for debate. The city has decided to use the drilling revenue from around and under the city-owned Lake Worth reservoir to improve the lake and its surroundings. The initial plans call for dredging the lake and better connecting the 18 dedicated lakeside parks with one another and the Fort Worth Nature Center.

But the plan also called for selling about 70 percent of another 1,000 acres the city owns in the area that is vacant but not yet dedicated as parkland. The staff idea was to attract developers, who would create mixed-use developments to include housing, office, and retail spaces.

That didn’t fly with the locals, who want the city to combine the 1,000 acres with existing parkland to create a badly needed major regional park. So the city went back to the drawing board.

The most expensive part of developing new parks is the cost of acquiring the property. Joe Waller, president of the Lake Worth Alliance, said the city has “the opportunity to enhance an existing park system in an extraordinary and cost-efficient way that will be beneficial to all the citizens of Fort Worth.” Waller also pointed out that this could be done without using tax money, just gas-drilling funds from the lake property.

“When they presented that plan to sell the property for private development, they weren’t really listening to any of us out here,” said Waller. “But they heard the opposition and are back working on the plan. We’re still hopeful we can create a great park system around the lake, and I think they are listening to us better now.”

“When they presented that plan to sell the property for private development, they weren’t really listening to any of us out here,” said Waller. “But they heard the opposition and are back working on the plan. We’re still hopeful we can create a great park system around the lake, and I think they are listening to us better now.”

When I moved to Fort Worth two decades ago, I was surprised there were no public pools my daughter could use in the Near Westside neighborhood we lived in. In fact, there were no public pools on the West Side at all.

I asked my neighbor why that was. “Oh, we have pools over here,” he said, laughing. “Just join Rivercrest or Colonial Country Club, and your daughter will have a nice place to swim.”

But then he got to the heart of the matter. “We don’t want public pools over here, because they bring the wrong element,” he said. In other words pools are for the poor folks, and West Fort Worth didn’t need to serve that community.

Phyllis Allen believes that attitude is still around. “”Fort Worth has gotten so full of itself in recent years, becoming an enclave for wealthy and attractive people,” she said. “Drilling rigs are a priority more than anything else. But we can’t use that money to give kids a place to swim.”

“Who uses parks and community centers?” she said. “We all know the answer to that. Our community center is used every day by our seniors and kids, and these programs are so important. But we can see what is happening over on the East Side. We are not the city’s target demographic, and we are taking the brunt of the cuts.”

Surveys of Fort Worth residents show that parks are high on their list of priorities. But the city’s political and business leaders don’t seem to agree, at least not based on city spending.

“Fort Worth ranks fairly well among large Texas cities, but very poorly compared with similar-sized cities nationally,” Estes said. “I believe that in Texas culture, parks generally do not rank as high with most people as do roads, bridges, and other infrastructure projects. Once a pattern is established, it is very hard to change it. For Fort Worth, funding for parks is not nearly as high a priority as in Austin or Seattle.”

The bottom line is that Fort Worth appears to be at a crossroads in the care and development of its park system.

The Lake Worth plan could increase the city’s total park acreage by about 10 percent if it’s all left as open space

Another potential big win for the city park system is the 2,000 acres of tall-grass prairie near Benbrook Lake that the Great Plains Restoration Council, led by activist Jarid Manos, wants to preserve.

While the city initially was on board with that project, nothing has been done now in about five years. The 2,000 acres is owned by the state, which wants $21 million for the property. Additionally, the Southwest Parkway will run right through the middle, and some state and local officials think it’s a better idea to sell the prime property to private developers to bring in revenue to the state and city.

The Trinity River Vision project could open up major stretches of riverfront to recreational use by removing river levees in some places, but there’s a big question about how much of that access will remain public and how much will be turned into patios for expensive restaurants. The redoing of Gateway and Riverside parks for TRV floodwater storage could result in other major changes, potentially adding features, but at the cost of annual flooding and possible environmental problems.

The city also seems interested in doing more partnerships with private entities like the YMCA, but residents are balking at such plans. A recent proposal to privatize the Fort Worth Botanic Gardens — much as the city did with the Fort Worth Zoo many years ago — created so much opposition that the plan was scrapped.

Crompton, who serves as mayor pro tem for the city of College Station as well as teaching at A&M, said making the right decisions during tough economic times is critical.

“People are looking at quality-of-life issues right now as an important factor in where they want to live, and they will take a lesser salary to move to places they want to,” Crompton said. “Parks have a lot to do with that. If you cut back too much right now, you will probably never make it back to where you were before the cuts.

“Fort Worth doesn’t have mountain ranges or oceanfront land,” Crompton said. “So you have to work harder to match places like those. And that takes a commitment from the public and the local government to make a livable and sustainable community. Without a good parks system, that becomes very difficult to do.”