The photo pages are filled with shots of masked men holding large guns, some with the U.S. flag tied around their lower faces. There are tips on how to stockpile ammo and hip-hop videos promoting armed revolution. And the rhetoric is inflammatory. A Garland man who created a group to oppose the “insane tyrant Obama” wrote, “Maybe when they show up, the 21-gun salute [should] be made into a 21-gun firing squad.”

Another page, covered with images of masked men bearing arms, orders their underground chapters to “gain all useful knowledge and become proficient in the tactics of guerrilla warfare, sabotage, assassination, intelligence gathering, infiltration, clandestine communications, and psychological operations.”

Another page, covered with images of masked men bearing arms, orders their underground chapters to “gain all useful knowledge and become proficient in the tactics of guerrilla warfare, sabotage, assassination, intelligence gathering, infiltration, clandestine communications, and psychological operations.”

Those words and images aren’t contained in closely held documents read only by the membership of some small radical group. They, and other material like them, are posted on Facebook and other social media, accessible to millions of people and read, at the very least, by thousands more people than likely would ever pick up a ring-wing printed pamphlet.

You might think that Facebook, with its well-publicized lack of privacy, would be the last place that paranoid, insular groups would choose as a place for organizing. But the reality is that a wide range of far-right organizations are using social networking sites like Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, and YouTube to recruit members, spread their philosophy, and even, in some cases, to espouse violence and other illegal activities. For some groups, Facebook pages become a sort of central command — their meeting place, operating manual, source of information and inspiration, and outreach tool.

Not surprisingly, a lot of the activity is emanating from Texas, home to patriot and resistance groups ranging from the extreme to the more moderate. The Central Texas Militia, known as the most active of Texas’ various independent militias, conducts outreach, organizes training days, and networks with other organizations through Facebook and MySpace. The Texas Three Per Centers, a group centered around Second Amendment rights who “are willing to fight, die and, if forced by any would-be oppressor, to kill in the defense of ourselves and the Constitution” use their members-only group as a central hub for communication and organizing among their five regional groups in Texas. There are Texas chapters of “the Rogue Nation Eternal Militia,” which will use “Any Means Necessary” to protect liberty, including guerilla warfare and assassination. And individual Texans belong to groups like the Sons of Liberty, which quotes John Locke in its mission statement, about the duty of the people to overthrow an oppressive government: “In the future, if need be, the new ‘sons of liberty’ shall and will take back control of this nation.”

Much of the material on these groups’ pages, while disconcerting, clearly does fall under free-speech protections. Other more abusive material violates Facebook guidelines, resulting in some posts being taken down and posting privileges being rescinded or suspended. But other disturbing material has been allowed to stay up for weeks and months. Federal agencies have even arrested posters whom they deem to be threats, and posts have been used as evidence of premeditation in violent crimes.

Legally, terroristic and inflammatory statements are just as prosecutable if they’re posted on Facebook as if they were spoken at a rally or written in a book or newspaper.

Legally, terroristic and inflammatory statements are just as prosecutable if they’re posted on Facebook as if they were spoken at a rally or written in a book or newspaper.

In 2009 a California appellate judge ruled that MySpace posts are in the public domain, since it is “available to any person with a computer and thus open … to the public eye. Under these circumstances, no reasonable person would have had an expectation of privacy regarding the published material.”

However, the reality is that very few participants in violent, over-the-top communications ever get prosecuted. Law enforcement agencies do keep a watch on what goes up on many radical sites, but few posts legally cross the line into threats specific enough to warrant arrest. Moreover, there is still confusion about how much those agencies can use such sites during investigations if the posters have not yet committed any crimes.

Facebook has a policy against any post that is “hateful, threatening, or pornographic; incites violence; or contains nudity or graphic or gratuitous violence” that violates someone else’s rights or the law … or is used to “bully, intimidate, or harass any user.” If you violate those rules, your post can be deleted or you can get kicked off Facebook.

“The goal of these policies is to strike a very delicate balance between giving people the freedom to express themselves” and maintaining a safe and trusted environment, explained spokesman Andrew Noyes.

Facebook has disabled people’s sites and take down certain posts. Brian Anderson, the Garland man who created the “P.A.T.R.I.O.T … People Against This Ridiculously Insane Obama Tyrant” group (which has 215 members) was temporarily blocked from using certain features because of what he wrote about the 21-gun firing squad (on a page about the Westboro Baptist Church’s protest of military funerals).

Robert Kenehan, a member of the Central Texas Militia and a Three Per Center (who doesn’t want his exact location revealed for security reasons), was denied permission by Facebook to post certain links. He has also received numerous warnings about posts that, in his words, “don’t go along with the Corporation of America’s agenda.” He even had his account disabled a year ago. His new page is filled with information about the New World Order, the birther movement, links to various independent non-state militias, and images like the one of him holding a semiautomatic weapon in front of a “Don’t Tread on Me” banner and an American flag. Where do you draw the line?

To some, Facebook’s actions might seem like censorship. “You don’t want Facebook and Twitter to be the arbitrators of speech and ideas,” said Ryan Kalo of Stanford Law School’s Center for Internet and Society. “But you also don’t want them to be a place where certain people feel unsafe.”

The web sites’ decisions on who and what to censor can seem arbitrary and haphazard. But even if they take down posts that technically should be allowed, people have no legal recourse. Numerous Native Americans, for instance, have been deleted from Facebook because site officials assumed that their names were fake. For example. one Native American woman with the last name “Kills the Enemy” was banned from the site.

The First Amendment only protects people against actions by government, said Gene Policinski, executive director of the First Amendment Center. “Facebook isn’t the government.”

Thanks to the federal Communication Decency Act of 1996, web site operators can’t be held legally responsible for anything that users post — including hate speech or illegal threats — but they also have the right to take down any posts that they deem inappropriate or that violate their terms of service.

Noyes said Facebook “regularly” has to remove pro-terrorism posts and has set up a separate page for users to report that kind of thing.

But a simple search through various groups’ and individuals’ sites makes it clear that Facebook isn’t keeping up with the problem. For example, it was only after CNET alerted them that Facebook operators disabled a month-old open-to-the-public “Kill Obama” page with 122 members. One of its goals read: “We are going to kill Obama. Ten of us will surround the capital, armed with sniper rifles. Mr. Hope And Change just made his last speech.”

A look through the web pages of radical right-wing groups offers a glimpse of oft-hidden worlds. The pages are filled with photos of AR-15s, Sarah Palin signs, eagles, and hot chicks with guns. There are lots of flags — American, Confederate, and the coiled-snake emblem known as the Gadsden flag. Images of the Founding Fathers sit next to those of Obama depicted as a socialist in front of the Russian flag. There are videos of militia trainings and, particularly on the more extreme sites, directives for supporters to resist the “New World Order” — the so-called one-world totalitarian government conspiring to take control of the planet.

Members share information about boycotts and political candidates, conduct outreach, and invite one another to meetings and events, from monthly sessions at the local pizza shop to military training. The Texas Well Regulated Militia’s new Facebook page, for instance, features a post calling for members to “provide security” at a counter-protest in Austin regarding Arizona’s immigration law. The Central Texas Militia posts notices about upcoming meetings and trainings. The Rogue Nation put up a special video announcing that American society has reached the “point of no return” and that it’s time to “alert, mobilize,” and begin “precautionary and proactive operations.” Another post declares, “We need to train to raid and carry out strikes but don’t act until the war has publicly begun or you will condemn us all!!!!!!!!!!!”

While it seems odd for groups that believe the government is corrupt to put their anti-government plans out in plain sight, in another way it just marks the radical groups as having the same needs as any other political organization. Grassroots political movements from MoveOn to Obama’s election volunteers to the Tea Party groups have to work the social networking sites to succeed. Likewise, right-wing extremist groups realize that the reach and efficiency of these sites can’t be duplicated.

While it seems odd for groups that believe the government is corrupt to put their anti-government plans out in plain sight, in another way it just marks the radical groups as having the same needs as any other political organization. Grassroots political movements from MoveOn to Obama’s election volunteers to the Tea Party groups have to work the social networking sites to succeed. Likewise, right-wing extremist groups realize that the reach and efficiency of these sites can’t be duplicated.

It’s particularly essential for groups like the Rogue Nation that use the leaderless resistance model, in which organizations operate as a network of small, dispersed, yet interlinked groups and individuals, with no easily identifiable leader. It eliminates the weak link of central leaders who historically have been targeted by governments and proved vulnerable to internal disputes within movements. Popularized in 1962 by former Klansman turned Aryan Nationalist Louis Beam, it’s a structure that is used by groups from the left-wing anarchist Earth Liberation Front to al Qaeda.

The photocopy machine made pamphleting easier, and telephones aided outreach, but social networking has influenced the very essence of organizations. The Oath Keepers, for example, which has a strong presence in Texas, struggled with whether or not to have an official Facebook page, since founder Stewart Rhodes realized he couldn’t stop people from posting things like calls for armed resistance that contradicted his message and mission. Online, an informal version of the group took on a life of its own and became greater than the founder and the official organization itself.

Social media encourage cooperation among factions, allowing them to work together on issues they do agree on. “If you physically put these different factions in a room together, they would fight. Online they can sound off and vent instead of exchanging blows and agree to put aside their difference. At public rallies you will find the whole spectrum invited to join together and show a strong presence in the real world,” explained Brian Marcus from the Anti-Defamation League. There is crossover among various radical-right groups as well as links to Tea Party groups and more mainstream campaigns like that of U.S. Rep. Ron Paul of Texas.

When calls for violence and other inflammatory language are so prevalent, they begin to sound like the meaningless hyperbole that fills the hours on talk radio and late-night TV. In fact, some label the people who post such things “keyboard commandos,” implying that they are all bark and no bite.

Dave Moore, from “Deep in the heart of Texas,” posted on his MySpace page (where he goes by the user name of Tyranny Response Team), “I will stand and fight for ole glory until my last breath. And if I die doing this I will die with honor and dignity.”

Texan “Mike Price III,” a member and active online recruiter of the Oath Keepers, Minutemen, Three Per Centers, and the Texas Well Regulated Militia, said he doesn’t advocate violence. But he posts comments like “We will fight fire with fire. If tyranny ever fires the 1st shot. Our forefathers did. We fight with honor and dedication to God, country and family.” And “Texas is in the FIGHT. Go home Illegals and repeat criminals your days are numbered.”

Such statements are considered too vague to constitute real threats. To be prosecutable, threats have to be both imminent and likely — not advocating an illegal action at some indefinite time in the future.

Policinski, of the First Amendment Center, said most such posts are completely legal. “You don’t want to suppress ideas, because that becomes thought control,” he said.

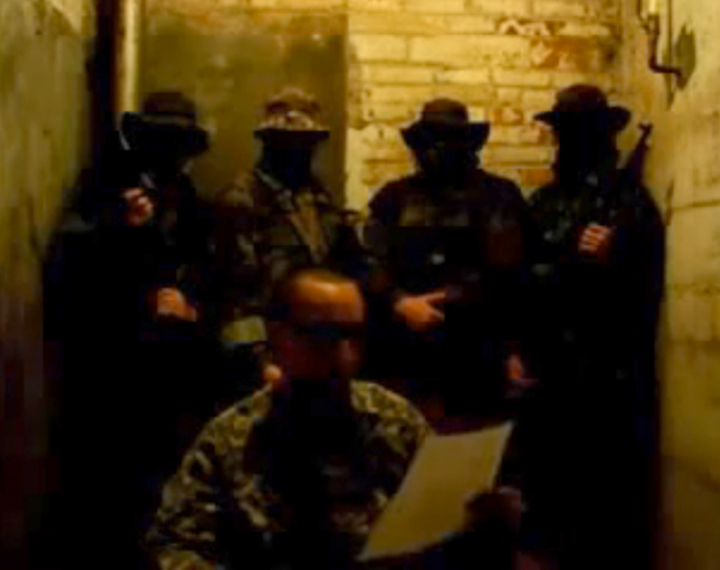

Other postings seem to be clear threats of murder and other violence. The “Warning to the New World Order” video posted on the MySpace page of a Texas chapter of the Rogue Nation Eternal Militia, features five men in a bunker wearing camouflage, some armed, all with their faces in shadows, reading a letter from the RNEM. “We may go ahead and strike first and remove you from the face of the earth,” it reads. “We will fight to the death and take you with us. You should never sleep easy because you never know when you will wake up in the middle of the night with a Columbian necktie and us standing over you laughing as you take your last breath.” The militia types are alerting the “New World Order” that they are keeping an eye on them. But that goes both ways.

Members of Texan chapters of the American Resistance Movement (who wish to remain anonymous) have told me that such videos, posts, and photos are meant solely as intimidation techniques and that there is no intention to carry through with the threats. But how are outsiders — and law enforcement agencies charged with protecting the public — supposed to know who is serious and who is not?

Specific threats, particularly those against the President, are taken more seriously. During the healthcare reform debates, numerous tweets called for Obama’s assassination. Solomon “Solly” Forell wrote, “We’ll surely get over a bullet 2 Barack Obama’s head!” Jay Martin, a.k.a. Thheee_Jay, posted a series of tweets including, “You should be assassinated @BarackObama” and “If I lived in DC I’d shoot him myself. Point Blank. Dead Fucking Serious.” The Secret Service investigated and interviewed Martin and Forell but determined they posed no serious threat.

Some of Daniel Knight Hayden’s tweeted threats to “start the killing now” at a Tax Day protest, are still up on Twitter. Under the name CitizenQuasar, he tweeted:

7:59 p.m. “The WAR wWIL start on the stepes of the Oklahoma State Capitol. I will cast the first stone. In the meantime, I await the police.”

8:01 p.m. “START THE KILLING NOW! I am wiling to be the FIRST DEATH! I Await the police. They will kill me in my home.”

8:06 p.m. “After I am killed on the Capitol Steps like REAL man, the rest of you will REMEMBER ME!!!”

8:17 p.m. “I really don’ give a shit anymore. Send the cops around. I will cut their heads off the heads and throw the on the State Capitol steps.”

When the FBI investigated Hayden, they found similar anti-government language on his MySpace profile, which was used against him. He was charged with sending threatening communications across state lines, found guilty, and sentenced to eight months in prison. Other threats made via social media, usually of personal rather than political violence, have also led to arrests or been used as evidence that criminal acts were premeditated.

When the FBI investigated Hayden, they found similar anti-government language on his MySpace profile, which was used against him. He was charged with sending threatening communications across state lines, found guilty, and sentenced to eight months in prison. Other threats made via social media, usually of personal rather than political violence, have also led to arrests or been used as evidence that criminal acts were premeditated.

Facebook is clearly a gold mine of information, one that private businesses, at least, are gladly taking full advantage of. But when it comes to the government using social media to track violence-promoting groups, the picture isn’t so clear.

Government agencies, just like any citizen, can monitor Facebook and other sites. But just as a cop working a beat can’t pull someone over because of the color of his skin, law enforcement agents aren’t allowed to hack through passwords to see private information just because someone posts inflammatory comments or quotes Thomas Jefferson. They must balance free-speech and privacy rights with their responsibility to stay informed on potentially dangerous groups.

“There are First Amendment issues that we are aware of and must respect,” said FBI spokesman Paul Bresson. “There has to be some type of criminal predicate” for agents to go beyond what is available to the general public, he said, and there are constitutional and other limits to what they can do.

But once law enforcement agencies believe they have good reason for thinking there is a threat of illegal activity, they usually can get permission to search any online content. “No matter how protected — you could be behind 30 passwords — it doesn’t stop the government,” explained Stanford Law School’s Kalo. “With enough due process, they can get anything.”

Beyond those general rules, federal agencies are still sorting out their guidelines for how and when they can use social networking sites as investigative tools. For instance, there is still debate about whether agents can create a fake profile in order to befriend someone on restricted pages.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) filed a Freedom of Information Act request in December 2009 for federal agency policies regarding the monitoring of online networks. The Internal Revenue Service, Department of Justice, Secret Service, and Central Intelligence Agency provided information. Other agencies, including the U.S. Marshals and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, said they had no such policies, which raises the question of whether they are making little use of the web sites or doing whatever they please, Wild West style. According to EFF, it is still reviewing a response provided by Homeland Security in May, and the FBI is expected to reply in July.

The Justice Department monitors questionable sites but hasn’t come up with an answer to whether its agents are allowed to go “undercover,” taking on fake personae and “friending” people. The IRS searches the sites for mentions of side businesses for which taxpayers may not be reporting income, but it has strict guidelines that allow agents to use only sites that don’t require logging on. Last year the IRS even created a PowerPoint presentation that it shares with other governmental groups explaining how to monitor these sites.

The networking sites also vary in how they respond to law enforcement requests for information. Most social media organizations allow government agencies access to participants’ information in emergencies, but they have differing views about voluntarily alerting law enforcement to folks who use their sites to make illegal threats and on opening their vast storehouses of information to broader inquiries.

MySpace, which stores current users’ information indefinitely, requires a search warrant for any private messages, bulletins, or friends lists that are less than 181 days old. It is unclear whether MySpace makes older information easily available to federal agencies. Twitter preserves very little data — for instance the organization keeps only the last login IP address a poster has used. If a federal agency wants any information — even for it to be saved to be accessed later — Twitter requires that the agency go through formal legal processes.

According to the Department of Justice, Facebook is “often cooperative with emergency requests.” Facebook’s Noyes declined to comment on whether his company volunteers information to the FBI or other agencies, including the kind of pro-terrorism posts it asks readers to report. The web site records and stores all sorts of user information, including what people have viewed and posted on the site, even if the items have been deleted. That database would seem to be an obvious source for law enforcement agencies, but it’s unclear whether they ask for — or get — access to such archived information.

It’s not that the extremist groups are so naive as to think they’re not being monitored. Far from it. The Rogue Nation encourages some chapters to be public and make full use of social networking sites for outreach but keeps other groups underground for more covert activities. In a threatening letter to the “New World Order,” Rogue Nation leaders pointed out that it goes both ways: Thanks to the internet, they are keeping tabs on their perceived enemies as well and know who they are and where they live.

Members of the American Resistance Movement, which trains for potential defensive action should the U.S. impose martial law, debate how much of a presence to have online. Their Facebook administrator posted that he “wants everyone to stay vigilant and careful about what you discuss to strangers, we are all living under the Patriot Act now and must act accordingly. remember it does the movement no good if you are sitting in a federal prison.”

On their group’s regular web site, the moderator warned members to delete all social networking profiles and links to YouTube videos. “This is for security reasons, we just would like to guard and keep our member safe from trolls, loyalist, reporters and everything else, remain anonymous and enjoy,” the moderator wrote.

But another member replied, “Does it really matter if they know who we are? I know I want them to know that we are out here and are not scared of them!!!! Transparence is something they know nothing about.” Part of the reason for posting calls for revolution on Facebook is that it is a public forum, and anyone — including the federal government — can see it.

“Facebook probably is monitored just as much as everything else — probably more so,” said ARM member and Three Per Center Bradley Clifford, who used to run the ARM online forum. “That, however, should not stop anyone from exercising their rights. If we just hide and not exercise those rights … we may wake up with none.”

Perhaps one of the most disturbing aspects of such rhetoric on social media is that in some cases it actually seems to be influencing the public debate in the direction of over-the-top, violent-sounding sentiments.

Bill Bychowski, who posts about everything from getting Tea Partiers into Congress to the evil that he sees behind healthcare reform to stockpiling weapons, points out that Facebook messages also reach those running for office.

“Mostly politicians are copying the [Facebookers’] phrases, using the terms ‘revolution,’ ‘don’t retreat, reload,’ ‘born again Americans,’ ‘Global WAR-ming,’ ” he said. “They are paying attention.”

Freelance journalist Justine Sharrock’s new book is When Good Soldiers Do Bad Things, about the homecoming of soldiers from Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. She writes for Mother Jones, the San Francisco Chronicle, and other publications.

A version of the story first appeared on AlterNet.