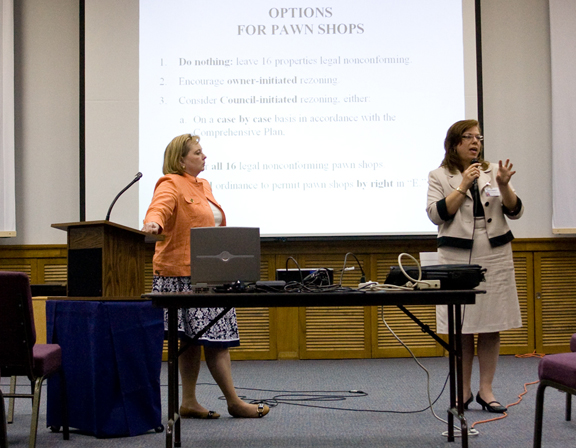

The Fort Worth City Council meeting on May 4 was an evening session, and council chambers were packed, mostly with residents who had come to oppose a change in the city’s zoning ordinance that would loosen the restrictions on pawnshop operators, many of which have payday loan operations in their stores.

Mayor Mike Moncrief opened the zoning hearing with a call for civility. He cautioned the crowd to be respectful of others’ views and vowed that no one on the council would be allowed to attack anyone who came before it, because, he said, that’s “the Fort Worth Way.”

That “be nice” admonition lasted about 10 minutes — until Libby Willis came to the podium.

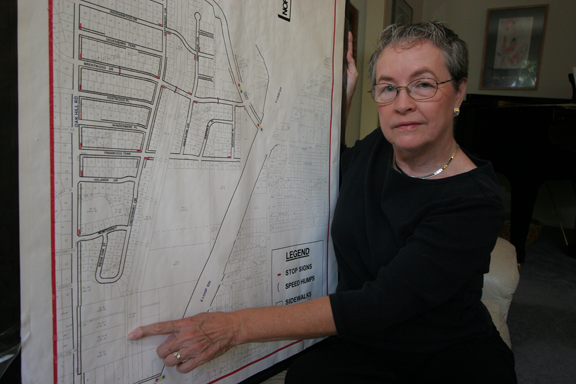

Willis, president of Fort Worth’s League of Neighborhood Associations, said she spoke on behalf of almost 100 of the city’s approximately 300 neighborhood groups that opposed the proposal: a change being pushed by the city council majority despite opposition from the city staff, the zoning commission, and the two council members whose districts were most affected. Willis got a rousing ovation from the crowd when she finished her presentation with a plea for the council to heed the voice of its citizens.

Willis, president of Fort Worth’s League of Neighborhood Associations, said she spoke on behalf of almost 100 of the city’s approximately 300 neighborhood groups that opposed the proposal: a change being pushed by the city council majority despite opposition from the city staff, the zoning commission, and the two council members whose districts were most affected. Willis got a rousing ovation from the crowd when she finished her presentation with a plea for the council to heed the voice of its citizens.

But before Willis could sit down, Moncrief called her back. Council member “Zim” Zimmerman was waving his cell phone and telling her that he’d just called representatives of two neighborhood groups, who said that they had not spoken to Willis.

She tried to explain that others had made some calls for her and had told her that the two groups in question indeed opposed the change. Zimmerman began demanding that she provide documentation for every neighborhood group she claimed to be speaking for. Then the mayor chimed in to ask if all those groups were part of the league. Willis said that she’d called neighborhoods in the league and others that weren’t (but were affected by the proposal), but again she was interrupted –– rudely, her angry supporters say –– by Moncrief. “Just answer my question,” he snapped.

Fort Worth has more neighborhood associations than most cities of its size, and in past years, neighborhood leaders say, they’ve worked closely with city hall on all kinds of issues. But in recent years, that relationship has begun to change –– for the worse.

Many neighborhood representatives now say they believe they and their views are less welcome at city hall, that important decisions affecting their areas are being made without consulting or in some cases even informing them, unless it’s almost too late for them to organize effectively. And when the neighborhood folks show up at city hall anyway, no one is listening.

Some see an organizing principle at work here. From gas drilling regulation to pawnshops to park protection, these leaders say they see city hall as protecting the interests of money –– drillers versus the people who live near wells, the rich part of town versus the not-so-rich, pawnshop corporations versus the people who end up paying enormous interest rates for payday loans –– rather than the interests of citizens.

“We worked hard to bring down the wall between the city [hall] and neighborhoods, but [some] city council and staff seem to be rebuilding it,” said Tolli Thomas, treasurer of a neighborhood group on the southwest side of town.

Thomas and many neighborhood organizers think they see a possible solution: They are calling for changes in the city’s charter, to increase the number of people on the council. “Centralized power in this town has failed in every respect,” Thomas said.

In the Riverside area, the Oakhurst Neighborhood Association has been fighting the city on a variety of issues, the foremost of which is their effort to save Riverside Park, which the city has proposed to use as floodwater storage as part of the Trinity River Vision project. Oakhurst leaders believe the proposal –– which basically involves cutting away a large section of the park and then declaring the bottom of the resulting hole to be the new park surface –– would create an environmental hazard and a traffic logjam and would render the park unusable.

“Riverside is being carpet-bombed by the programs that the city has decided to push,” said attorney and neighborhood resident Robert Gieb.

The group has had numerous meetings with city officials, including their own council representative, Sal Espino, only to be told they don’t really represent the area.

The neighborhood association has been around for decades, but when push came to shove over the park dredging proposal, the city recognized a small, newly formed minority group instead of Oakhurst –– and the Oakhurst leaders say they believe it was done because the other group would go along with whatever the city proposed.

Gieb believes city officials have targeted his neighborhood because they are too scared to take on the wealthier West Side, where the new flood storage area originally was supposed to go. However, when that portion of the plan was revealed, the very rich landowners who were targeted to lose their properties raised such hell, threatening lawsuits, that the floodwater storage area was suddenly diverted to the East Side.

“They’re afraid to take on Rivercrest, and they think that we’re stupid,” Gieb said. He figures city hall thinks the neighborhoods are too weak to oppose their power grab. “They undermine the old neighborhood organizations that really represent the people and have elections,” he said.

When the excavation of their park was proposed, Espino at first vowed that the project would not proceed without the approval of the Riverside neighborhood associations. In three of the four open meetings, the Riverside Park project was voted on, and the majority of those voting opposed it, according to the League of Neighborhood’s president Willis.

At one of the meetings in March, she said, Espino told the group that they did not represent the majority opinion in the neighborhood and that he would not allow a vote on the matter.

“He said that the group was not representative of Riverside,” she said. “We had four of those meetings, and there were big turnouts for all of them. At all of those meetings, the majority of the people present, who represented at least four Riverside neighborhoods, were against the plan for flood storage in the park.”

A splinter neighborhood group, comprising a small group of dissident Oakhurst residents, formed their own group, the Oakhurst Neighborhood Redevelopment Organization. The group showed up at council meetings, claiming to represent the neighborhood. They supported the Riverside Park project.

Janice Michel, one of the founders of the new group, who also served as a zoning commissioner for six years, said that she and a few other women started the group because they felt that the Oakhurst Neighborhood Association was being taken over by Willis and a few others and no longer represented the neighborhood.

Janice Michel, one of the founders of the new group, who also served as a zoning commissioner for six years, said that she and a few other women started the group because they felt that the Oakhurst Neighborhood Association was being taken over by Willis and a few others and no longer represented the neighborhood.

On important issues, she said, “The executive board would just decide how the neighborhood felt about it and go down to the council and state [their views]. The people in our neighborhood wouldn’t know anything about it.”

According to Michel, who also was one of the founders of the Oakhurst Neighborhood Association, the need for a new group arose when Willis became the group’s vice president. Until then, she said, every member could vote on issues. But because of a section of the organization’s bylaws that Michel had previously overlooked, that practice changed.

“[Willis] realized that in our bylaws that only the street reps voted,” she said. “We had never done that. If you owned a home in Oakhurst and came to the meetings, you could vote on anything. All of a sudden, we were told we couldn’t vote.”

Leslie James, a resident of Oakhurst for 25 years, believes that the new organization is a puppet group, with the city pulling the strings. “They’re not listening to us,” she said. “They apparently decided that this new splinter group is who to listen to. [The new group] believes that this flood storage is a good thing. There are 700 homes in Oakhurst, and 12 people go to their meetings.”

The city recognized the group as legitimate, despite the protests of Gieb, Willis, and others. The city said other Oakhurst residents would just have to “deal with it,” Gieb said.

According to the Oakhurst Neighborhood Redevelopment Organization’s bylaws, any resident of the neighborhood can be a voting member. So when the new group posted notices of a meeting, 28 members of the Oakhurst Neighborhood Association showed up.

According to Gieb, there were only about a dozen people there, one of whom was Espino’s assistant. Gieb inquired about the group’s parliamentary procedures and discovered that the group had not elected officers, nor did they vote on their positions. The group’s leader, Nancy Smotherman, said that they “discussed” the matters and “decided.”

According to Gieb, there were only about a dozen people there, one of whom was Espino’s assistant. Gieb inquired about the group’s parliamentary procedures and discovered that the group had not elected officers, nor did they vote on their positions. The group’s leader, Nancy Smotherman, said that they “discussed” the matters and “decided.”

Gieb called for an election on the spot and was voted the president of the organization. After being thrown out of Smotherman’s house, the group continued the elections on the street and voted to reverse the splinter group’s support of the Riverside Park project.

However, Espino’s assistant reported to the city that the meeting had been adjourned before the elections ever took place.

“We had a bona fide election on their terms, and they lost,” Gieb said.

Michel said that the city corresponds with her group because it’s legitimate. “We did everything we’re supposed to,” she said. “We’re not like a neighborhood association. We didn’t have to be voted in. We’re the founders of a neighborhood redevelopment organization.”

The city still recognizes the redevelopment organization and communicates with them regularly, which is more than the long-standing Oakhurst Neighborhood Association can say.

“We didn’t toe the line with the city, so the city realized that [the splinter group] would do anything that [city officials] want them to do,” said Gieb. “They hooked onto them and declared that they are a real organization.”

Sal Espino would not speak to Fort Worth Weekly but did issue a statement regarding the contoversy over Riverside Park:

“Riverside Park is a community park which serves a diverse community of 21,000 residents … . Because of this rich diversity, there are different opinions on the Riverside Park Master Plan. There are folks who want improvements to the park and others who do not. … That is why we have a public process so citizens and residents can express their opinions.”

Many neighborhood leaders also complain that the city doesn’t give them enough notice when changes are being proposed that affect them –– perhaps only a week before the impending changes are to be voted on by a council or a commission.

Joe Waller, president of the Lake Worth Alliance, said changes in zoning and development standards make it difficult for ordinary folks to weigh in. “We’ve had developers wanting to come in and change zoning rules, and we get notice that it will be on the zoning commission agenda just a week ahead of time,” Waller said. “The developer has already met with the city planning staff, they have their attorneys that have a marketing plan, and we have very little time to get organized.”

Plus, “these commissions and city council meetings often take place in the daytime,” he said. “We all have jobs we have to go to during the day. So if we could have these meetings at night and get more lead time on policy changes and zoning issues, it would work better for us. But how it works now, it is very difficult to get a fair shake.”

Thomas, treasurer of the Wedgwood Square Neighborhood Association, said her neighborhood in southwest Fort Worth had similar problems earlier this year. The city wanted to use U.S. Housing and Urban Development funds to tear down a foreclosed apartment complex and then build new apartment units targeted for the homeless.

But the city staff told the association that the apartments were not specifically for the homeless but would be “affordable” housing for those employed. It was only through questioning at a public hearing that Councilman Jungus Jordan and city staff acknowledged that the housing project was going to be used for the chronically homeless.

“It wasn’t that our neighborhood groups in that part of town were against the homeless, but we felt they just dropped this on us at the last minute,” Thomas said. “[Fort Worth] wanted to railroad through a public hearing just a few weeks before council was going to vote on it. At no time in the planning process did they consult with us to see how we felt about this issue and maybe get our opinions on what might work or not.”

City council eventually rejected the plan.

Thomas began volunteering in her neighborhood organization in 2002 and said things were very different back then. “There was always a lot of discussion with us,” she said. “We were consulted regularly. The city came to us and asked for our opinion.”

Thomas said Wedgwood is concerned about Chesapeake Energy buying lots of property in the area –– mostly commercial –– and has asked the city what developments the gas drillers might have in mind. No answers on that question. They have presented traffic planning suggestions to city staff, and no response on that one either.

Maybe it was the gas drilling, she said, an issue that put the city council at odds with thousands of its citizens who felt –– and still feel –– that the city has failed to protect their safety and health from the environmental dangers of drilling, compressor stations, and pipelines.

Maybe it was the gas drilling, she said, an issue that put the city council at odds with thousands of its citizens who felt –– and still feel –– that the city has failed to protect their safety and health from the environmental dangers of drilling, compressor stations, and pipelines.

“Perhaps they used that as an excuse to seek less input from us,” Thomas said.

Last month, the Eastern Hills Homeowners Association brought home third place in Neighborhoods USA’s 2010 “Neighborhood of the Year” competition. The neighborhood just east of downtown has 525 homes.

Richard Green, president of Eastern Hills, said that working with the city on issues “is about 50-50, meaning there are some things that work and some that don’t.”

For example, in recent years the neighborhood group worked with the city and councilman Danny Scarth to revitalize the three-acre Eastern Hills Park. “We were happy with how the park turned out, and it is an asset to the neighborhood,” Green said.

But the neighborhood group president also said the city often fails to communicate with neighborhood groups directly affected by changes. He said the handling of the special events ordinance recently developed by city staffers is a perfect example.

The proposed ordinance, which is being reviewed by a council-appointed committee and will likely go before city council in July, would rewrite the rules on how public events, including neighborhood-level celebrations from block parties to Fourth of July parades, are planned and regulated. Permit fees would go up, security deposits would be imposed in many cases, approval of street closures would be more difficult to get, and groups would have to apply 120 days ahead of time in most cases. And yet, on the other end, the most massive events in the city would be exempt from most provisions.

When the city council appointed a panel to study the situation, only one of 10 members was from a neighborhood association. The rest represented downtown business interests, chambers of commerce, and the convention and visitors bureau.

The city staff failed to approach community event organizers “to get our views on how these changes might be implemented,” Green said. “These associations would be affected more than anyone else in the city. Only after they drew up the draft ordinance did they ask us for input. They should have done that [first]. They had it backward.”

In 2002, Fort Worth had about 150 neighborhood and homeowner associations. Now, eight years later, the number has nearly doubled to 292. Some believe that fast proliferation is one of the factors in neighborhoods’ frustrations with the city.

The city runs a Neighborhood Office within the Community Relations Department. Christi Lemon, the neighborhood education manager, said the office provides information on city services, including the recycling program.

What the office doesn’t do is keep neighborhood groups informed of upcoming policy and ordinance changes that could affect neighborhoods. Lemon said it’s up to the specific city department involved in the change to do that.

Michel said that there are too many neighborhood associations that are controlled by just one person or a few people. That is the case in the Riverside Alliance, composed of the leaders of every neighborhood association in the Riverside area.

“Basically now you’ve got one or two people going to the Riverside Alliance speaking on behalf of their neighbors, and the people aren’t even a part of their organization.”

Willis said neighborhood associations are still an effective way for citizens to communicate with government. But she acknowledged that city hall has made that communication more difficult in recent years.

“I was at a zoning commission meeting last week, and there were 20 cases, and at almost every one there was some representative of a neighborhood association,” she said. “I think that demonstrates the importance of them. The zoning commission wants to know what the neighborhoods think.”

She said she doesn’t know why city hall is making it more difficult for citizens to find out what is going on. “If a neighborhood association submits a letter and takes a position on something, that should be enough,” she said. But “it seems like we’re having to make the point earlier and more often and en masse. It’s almost like they want us to turn out 300 people” for neighborhoods to prevail on an issue.

That May city council meeting ended with the council voting 7-2 to approve the loosening of restrictions on pawnshops, many with payday lenders in their stores. Council members Kathleen Hicks, who led the fight to oppose the change, and Joel Burns voted no.

Hicks’ opposition stems from the fact that her low- to moderate-income working-class district includes seven of the 13 pawnshops affected by the ordinance. “These are the very people that these predatory pawnshop/payday lenders prey on, the working poor,” she said. Burns’ district has three. His opposition came from the fact that, when he visited the three sites prior to the council meeting, all were out of compliance with city codes. (Three other districts have one affected pawnshop each; three districts have none.)

Hicks was stunned by the decision. Not only did the council ignore the recommendations of citizens, the zoning commission, the city staff, and Burns’ on-site inspections, but her colleagues also ignored her wishes.

When the issue first arose, council member Frank Moss said he made the proposal at the behest of Cash America, the nation’s largest pawnshop/payday lending corporation, with headquarters in Fort Worth. Hicks asked her colleagues to kill the proposal as a courtesy to her since her mostly minority district would be impacted disproportionately. At that point, council protocol and precedent should have stopped the proposal before it ever got to a vote, she said.

When the issue first arose, council member Frank Moss said he made the proposal at the behest of Cash America, the nation’s largest pawnshop/payday lending corporation, with headquarters in Fort Worth. Hicks asked her colleagues to kill the proposal as a courtesy to her since her mostly minority district would be impacted disproportionately. At that point, council protocol and precedent should have stopped the proposal before it ever got to a vote, she said.

“It is unheard of for the council to ignore one of its members on a council-initiated zoning change, when that change would have such a negative impact on the member’s district,” Hicks said. Still, she wrote in an e-mail, “I was very moved by the diversity of the residents who addressed the council [that night] … from all walks of life, from neighborhoods throughout [the city]. Big business might have prevailed, [but these] residents spoke with a united voice.”

Eastside activist and former president of the Brentwood-Oak Hills Neighborhood Association, Rita Vinson pointed out that night that just before the issue came to a vote, Cash America donated a strip of land near its headquarters on West 7th Street to the city for expansion of a Trinity River bridge. It may have been Cash America just doing business “the Fort Worth Way” as Moncrief said that night, referring to the pawnshop giant’s just being a “good neighbor,” but, Vinson said, “For those representing the interests of the public, the perception of a conflict of interest is as damaging as a real conflict.”

The mayor and several council members took umbrage with Vinson’s characterization of a possible quid pro quo on the land donation. Burns said that he was in the room when the offer from Cash America was made and that the pawnshop ordinance was never mentioned.

For Hicks and other longtime observers of city hall, the pawnshop issue is simply part of a troubling pattern that is only getting worse. “This whole thing was negotiated in back-door maneuverings, which is the norm for this mayor and council,” Hicks said in an earlier interview. “There is not a lot of public discussion anymore, on this or any other issue critical to the public. … Where is the public process? People need to be involved in these issues that affect their lives, but when things are being decided in the back rooms, the public loses. … We have to make sure everything is occurring in the public eye.”

Vinson is equally disgusted. “I’m ready to work on the next city council election,” she said.

Some observers see what is happening with neighborhood groups as part of a wider power grab by the mayor and council. In February, the council angered a wide cross-section of the community when council dissolved the citizen-appointed board of the city’s Crime Control and Prevention District and named itself as the new board.

That move was opposed by the Fort Worth Police Officers Association as well as members of the volunteer Citizens on Patrol, one of whom, Camille Drinan, said that she felt “betrayed” by the council decision — especially since the taxpayers had just been asked last November to reauthorize the district and its dedicated tax income for five more years. Opposition to the change was heated, with accusations flying that the city, facing a multimillion-dollar budget shortfall, just wanted to get its hands on the lucrative income from the crime-control tax district, an accusation that council members just as heatedly denied.

The council’s reasoning, according to Hicks, was because the legislature last session made it legal for boards of crime control districts to impose taxes on utilities within their districts. She said that the council did not believe taxing authority should lie in the hands of anyone but elected officials. Former members of the board argued that they had passed a resolution to the effect that the board would never use its authority to impose such a tax.

“I still believe that the real purpose is to have access to the funds in the CCPD coffers,” said one former board member who asked for anonymity.

There is no denying that the city is facing an unprecedented financial crisis, leading to budget cuts that Hicks said will hurt her moderate, low-income, and poor residents the hardest, especially the closing of all the city pools but Forest Park for the summer and the reduction of library hours. Forest Park, just south of the Cultural District, is hardly convenient for kids who live in the far south and southeast neighborhoods of Polytechnic, Stop Six, and Highland Hills.

“Folks are very upset about the pools,” Hicks wrote in an e-mail. “The city did get an agreement with the [YMCA] to open pools at a reduced cost, but it is still very bad for [the families in my district]. … Also, there is great concern that community centers might be closed and libraries in [the public housing compounds of] Butler Housing and Caville Place as a result of budget woes.” Because her constituents and other low-income citizens are unfairly bearing the brunt of the city’s financial crisis, Hicks said, she has voted against the budget for the last two years.

Thomas thinks the changes in the neighborhood-city hall relationship began around 2005, two years after Moncrief became mayor, though she can’t put her finger on a reason. Compared to five years ago, she said, there is now much less consulting and opinion-seeking with neighborhood groups. That’s roughly the same time that the city began fighting with increasing numbers of its citizens over its lack of regulation of the gas drilling industry.

It’s not that the neighborhoods see city hall as a consistent enemy. Vinson, who formerly worked for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, gives kudos to the planning division run by Deputy Director Dana Berghdoff and overseen by Assistant City Manager Fernando Costa, its former director. “There is a lot of knowledge, experience, and integrity there,” she said, “even as their recommendations get overturned by the council. … The pawnshop rezoning was just one dramatic example of this.”

Thomas and many other neighborhood organizers talk about reorganizing the council and creating additional districts. Currently, the average population per district is about 90,000. That is about twice the average for large cities in this country.

“We have grown so big now that we need better representation,” Thomas said. “Council members are so spread out, which makes it very difficult to respond to the needs of many neighborhoods. It would also decentralize the power a bit.”

At that contentious meeting on the pawnshop issue, Willis, a longtime neighborhood advocate and member of a prominent Fort Worth political family — she is the wife of Doyle Willis Jr., whose father was one of the longest-serving state representatives in Texas history — kept her cool. She told Zimmerman and Moncrief that she would provide the documentation they were asking for. At one point, she waved toward the audience, noting that many of the neighborhood reps who had given her permission to speak on their behalf were there. Could she have them stand up so that the mayor could do a head count?

“No,” Moncrief replied curtly. “That’s not the question.”

So much for the “Fort Worth Way,” Vinson said. “I would be happy never to hear the term again,” she said. “[It] began as a genteel expression to characterize the way we Fort Worth folks want to conduct business — polite and respectful –– but it has become degraded to the point of seeming smarmy or even worse: a tool for controlling and silencing opposition.”