One of the coolest moments last Saturday at the world premiere of Fort Worth Opera’s Before Night Falls happened before the first note was even struck or sung. In a “zine” handed out by the ushers along with the playbills was an announcement of next year’s festival. Along with Il Trovatore, Julius Caesar, and Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado, the company will tackle an ambitious chamber piece.

Uniting the surrealistic poetry of Allen Ginsberg with the distinctly post-classical music of Philip Glass, Hydrogen Jukebox has a lot in common with Tony Kushner and Péter Eötvös’ Angels in America, another purely contemporary piece and one staged, in 2008, by Fort Worth Opera. Clearly, the opera company –– along with Fort Worth’s three world-class museums –– is doing its part to drag “Cowtown” kicking and screaming into if not the early 21st century then at least, say, 1990.

Before Night Falls, based on gay Cuban poet Reinaldo Arenas’ 1993 memoir of the same name, was further proof that company director Darren Woods and his troops are at the vanguard of the artform. And judging by the packed house and rapturous post-curtain applause that greeted the production, we’re right there with them.

Before Night Falls, based on gay Cuban poet Reinaldo Arenas’ 1993 memoir of the same name, was further proof that company director Darren Woods and his troops are at the vanguard of the artform. And judging by the packed house and rapturous post-curtain applause that greeted the production, we’re right there with them.

Well, most of us. Last week, the Star-Telegram published a letter by Barbara E. Bettis, who complained that Fort Worth Opera, basically, didn’t publicize the fact that Before Night Falls includes a scene of men dancing suggestively with one another. Never mind the implied violence of the kind endemic to artful drama dating back to Aeschylus. Evidently, violence is A-OK! But romantic congress among same-sex couples? Uh-uh.

Fort Worth Opera marketing director Diane Rhodes Bergman responded in print a couple of days later, saying that, as with Dead Man Walking (2009) and several other Fort Worth Opera productions, the label “parental discretion advised” was attached to every piece of promotional material for Before Night Falls. “The statement ‘parental discretion advised’ is generic,” she said. “That is intentional. Parents have many different ideas about what is suitable for their children. We cannot tell parents what is suitable for their children; we can provide [parents] with the tools to decide,” meaning that parents are always welcome to read librettos beforehand.

On www.fwopera.org, Bergman also issued a disclaimer. “In an overabundance of caution, we want to be sure that you understand that this opera contains scenes of an adult nature. While there is no nudity, the real-life character the opera is based on was a homosexual, and there are brief scenes of intimate dancing between men. There are also scenes of violence, death, and strong language.” And smoking cigarettes.

Poor Barbara missed a helluva show.

The memoir was brought to life in all of its often cruel, often uplifting, always sumptuous and lyrical glory. Arenas was raised dirt-poor in Cuba in the 1940s in a “house full of angry women” and was afflicted at a young age by a yearning to transcend his humble surroundings. Arenas eventually found freedom in the form of Fidel Castro’s revolution, discovered his sexuality and artistic talent, found oppression in the form of Fidel Castro’s revolution, escaped Cuba, and discovered New York City circa the early 1980s. He committed suicide there in 1990 after a protracted battle with AIDS.

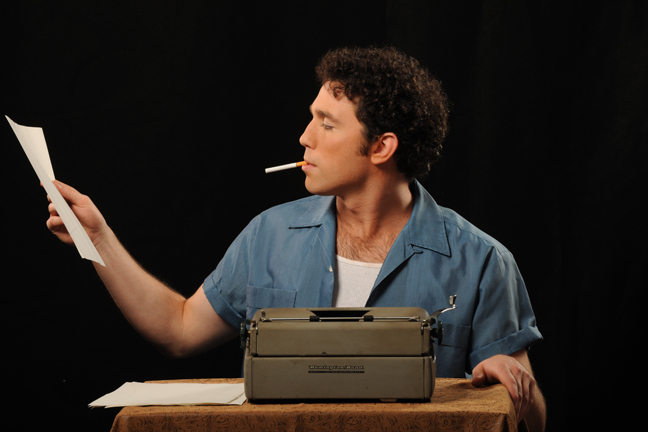

We first encounter Arenas (Wes Mason) toward the end of his life. He is being ushered to bed by Lázaro (Jonathan Blalock), an old non-romantic friend from the homeland. Arenas is a celebrated author and survivor of Castro’s Cuba but one who has found himself imprisoned by another despot: his love life. The harrowing sterility of the setting –– nothing but a single bed backdropped by projected imagery of monolithic, stoic, uncaring New York City buildings at night –– pointed up the oppressive banality of death. The resulting transition from deathbed to the sandy, tropical, palm-tree-strewn shores of Cuba was startling but also more than a little melancholy –– is there anything more pathetic than the sun-dappled dreams of a dying old man?

Were composer Jorge Martín and co-librettist (and Arenas translator) Dolores M. Koch trying to tug on our heartstrings? Perhaps, but the lyrical music and impassioned singing from the opening scenes rejected cliché. They also rejected notions of victim art. We merely were presented with a rounded-out character, one to whom Art-with-a-capital-A was paramount. For Arenas, art also represented a gracious form of immortality. As driven home by the production, Arenas never felt more alive, more “real,” than when he was creating.

Arenas and best childhood friend Pepe (Javier Abreu) join the revolution, spearheaded by Victor (Seth Mease Carico), a wannabe Fidel, cigar-filled beard and all. The promise of freedom of both the artistic and sexual varieties is soon squashed under Castro’s heel, forcing secret meetings among Arenas, Pepe, Arenas’ literary champion and contemporary Ovidio (the booming Jesus Garcia), and Arenas’ muses: The Sea (mezzo Janice Hall) and The Moon (soprano Courtney Ross). Arenas secretly submits his work to a French publishing house and is soon discovered by Victor, who tosses the burgeoning poet in jail and shows him a video of Ovidio confessing his counter-revolutionary transgressions and pledging allegiance to “the revolution.” Disheartened and dispirited, Arenas follows Ovidio’s lead and retreats into the anti-life of the oppressed. One last secret visit from Ovidio, who never stopped secretly championing Arenas, inspires the younger poet to forge his papers and catch the first ship to New York, where he is reunited with his old friend Lázaro –– but only for a short while.

Mason, a veteran of the esteemed Seagle Music Colony, is a shaggy haired, bronze-skinned, in-shape young man seemingly born to play Arenas. From the opening scene until curtain, Mason was never anything less than utterly believable, and he was in every scene, delivering the reams of lyrics laid on him naturally and without any hesitation –– and sometimes from flat on his back.

Mason also portrayed Arenas as a pathological seeker. Whether happily marooned on the beach with a dozen cavorting boys or cringing in pain upon the blank floor of his New York City apartment, Mason cut a probing figure, often peering into the distance (the audience?) with a seemingly visionary confidence.

Martín, who took several years to complete the adaptation, is obviously as interested in the highs and lows of Arenas’ life as he is in the rhythms of life. We’re far from Tchaikovsky, an obvious influence, but not really in terms of sheer post-romantic musicality. The vocal duets and trios were sunset lush, and the instrumental lines were joyously unpredictable (and only occasionally calculated), which is the sure sign of an artist with a vision. The music produced by the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra (under the direction of Joe Illick) could have been the score of Reinaldo Arenas’ colorful, contemplative, never-dull, Latin-flavored life. The folksy bossa nova-inflected flourishes and the brass section’s Modernist, almost film-noir honkings complemented each other in the spirit of Copland and Bernstein.

Before Night Falls is not necessarily an uplifting work and doesn’t really end. It just wafts away. Kind of like a last breath. Definitely not hot air.

Before Night Falls

2pm Sun, June 6, at Bass Performance Hall,

$17-134. 817-731-0833.