Steve and Marie Davis of Tyler decided to spend a romantic Valentine’s weekend in the Metroplex this year, a little spur-of-the-moment getaway. On Saturday night they hit Billy Bob’s for the Delbert McClinton show, not so much because they were big fans of the Fort Worth blues master as that they had never been to the famed honkytonk.

They had a few hours to kill before the show started, and Marie decided to try her hand at the bar’s slot machines. Yes, Billy Bob’s has slots – 15 of them near the men’s bathroom entrance. They’re legal because there is no cash reward when the three reels match up. Instead, the machines spit out tokens that can be redeemed at a counter for prizes like stuffed animals or key chains or t-shirts.

They had a few hours to kill before the show started, and Marie decided to try her hand at the bar’s slot machines. Yes, Billy Bob’s has slots – 15 of them near the men’s bathroom entrance. They’re legal because there is no cash reward when the three reels match up. Instead, the machines spit out tokens that can be redeemed at a counter for prizes like stuffed animals or key chains or t-shirts.

As Marie pulled the lever time after time, a reporter approached with a question: Would the couple favor an expansion of gaming options in Texas – resort-style casinos or maybe slots and video-game betting at horse tracks?

“We go to Las Vegas about twice a year, and we also go to Shreveport a few times a year,” Marie Davis said. “If they did nice casinos in Texas, with good hotels and restaurants and convention space, it would probably be a good thing for this state. I know we might come to Dallas-Fort Worth instead of Vegas if there was that option.”

Gambling proponents have been pushing just such an expansion for decades, but the votes have never been there in the Texas Legislature to put the issue before voters. There are some who think it could be different when the legislature meets again in 2011. Major budget shortfalls are looming, state services have already been cut to the bone, and casinos may be more palatable than tax increases for a lot of lawmakers. Billions of dollars in Texas money is wagered at casinos in Oklahoma and Louisiana every year. And according to polls done by gambling interests, nearly 70 percent of Texans want some form of legalized casino gambling here.

The forces on both sides of the issue are gathering in Austin. The gambling bill filed in 2009 never made it out of committee, but the legislature did authorize the convening of a rare House-Senate panel to study the subject during the interim. The committee will hold its first hearing in March.

“There will definitely be a better shot this time around,” said longtime Republican State Rep. Edmund Kuempel of Seguin, one of the authors of the 2009 bill. “We will have a large deficit, and we need to face that. But the great thing about this [a statewide ballot on gambling] is that we will let the people decide.”

Opponents think the arguments are strong on their side as well. Studies show that communities incur heavy costs for bringing in casinos and other gaming facilities: higher crime rates, bankruptcies, unemployment, lower rates of worker productivity.

Marie Davis knows a lot about that. She works as an addiction counselor in Tyler, dealing with drug and alcohol abuse and, yes, gambling addiction. So you might expect her to be wary of bringing big casinos to Texas, but that’s not the case.

“I have clients who are addicted to lottery scratch-off tickets, but the state still sells them to these people,” she said. “We allow topless bars, and some men get addicted to that as well. Alcohol is the worst, but we make that available to anyone who wants to drink.

“But those who get addicted to anything are a very low percentage of the total population,” she said. “Most people can handle gambling – it’s just another form of entertainment. If we have checks and balances here, with high-end casinos combined with good counseling programs, I don’t think it would be a problem. Plus we can keep money in the state to help fund things like education.”

She put in another quarter, pulled the lever, and a few more tokens plinked into the tray. Halfway to a stuffed monkey.

The Texas Legislature is gearing up for a tough session in 2011. The budget shortfall could be as high as $20 billion, partly because there won’t be another $12 billion in federal stimulus like Texas got in 2009 to help balance the budget..

The Texas Legislature is gearing up for a tough session in 2011. The budget shortfall could be as high as $20 billion, partly because there won’t be another $12 billion in federal stimulus like Texas got in 2009 to help balance the budget..

“We already cut down to the bone last time, and I just can’t see how we are going to do that again,” said State Rep. Jose Menendez (D-San Antonio), another author of the 2009 gambling bill. “No one wants to increase taxes. But if gaming is done right in Texas, we can increase tax revenues to the state by about $2 billion to $3 billion.”

The 2009 bill would have allowed “racinos” – slots and video game gambling – at the state’s five horse race tracks, plus up to 12 casinos in major metropolitan counties, on Galveston and South Padre islands, and on the lands of Texas’ three federally recognized Indian tribes. Tax revenue from the gaming establishments would have been set aside for college scholarships and transportation projects.

If, as expected, the bills filed for next year’s session are similar, one of the proposed casinos could wind up in the Stockyards. Though Fort Worth city leaders have taken no part in the debate in past years, many local business and political leaders think the Stockyards would be a natural, based on the heavy tourism component of that area (not to mention past associations with saloons and gambling). And Stockyards real estate powerhouse Holt Hickman has long pushed for a casino there.

Even if the sledding turns out to be easier this time around, getting a gambling proposal to voters is a long slog. And if it passes, it would still be at least a couple more years before the first casino could open – which means gambling money won’t be solving state budget problems anytime soon.

A gambling measure would involve a constitutional amendment, which requires approval by two-thirds votes of the Texas House and Senate. The governor gets no say on the proposed amendment – instead, it goes straight to the voters.

If voters statewide approve, a second vote would be required in each of the designated counties. If the local ballot also passes, license applications would be considered by a new state gaming commission. And only after that could construction begin.

The pro-gambling coalition is diverse – it includes Republicans and Democrats, conservatives and liberals. Some libertarian-leaning folks like the idea of paying for state services from voluntary spending rather than through tax increases. And the moral arguments against gaming have weakened somewhat in a state that now sells lottery tickets and allows pari-mutuel wagering at horse and dog tracks. Texas residents have access to offshore internet sports betting, and televised poker tournaments draw big audiences.

“I think any time there is a looming fiscal crisis, the chances [to broaden legalized gambling] improve,” said State Sen. John Carona of Dallas, another casino supporter. “It makes sense for the state to allow destination resort casinos but to limit the number and the locations.”

But gambling supporters aren’t in lockstep. Casino advocates want a broader range of games and lower taxes on their operations than at racetracks. Horsemen and track owners, however, want the same treatment as the “destination” casinos. And they do have the argument that their sport, more than 20 years into the current round of legal pari-mutuel betting in Texas, could use some financial help.

Texas has had a long history with gambling, both legal and illegal, and Tarrant County has been in the thick of it more often than not. Fort Worth’s Hell’s Half Acre offered plenty of brothels and gambling joints to trail-riding cowboys and other visitors in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The town’s movers and shakers played slots and poker in the Petroleum Club downtown in the first half of the 20th century.

In what is now Arlington, the Top O’Hill Terrace, which operated from the 1920s through the late 1940s, was once considered one of the most luxurious gaming establishments in the country. The first floor held a tea room and fine restaurant, but downstairs, bettors negotiated a maze of peepholes and doors to get to the action – and had a lot of exits to choose from in case of a raid. Next door, Arlington Downs horse track offered legal pari-mutuel betting from 1933 to 1937, (the legislature passed racetrack betting and then quickly rescinded it).

A gambling crackdown ended the Top O’Hill’s reign in the 1940s, but gambling continued in joints along Fort Worth’s Jacksboro Highway into the 1950s. The Four Deuces Club catered to the higher-end gamblers, and connections with paid-off law enforcement officials ensured that owners knew raids were coming in time to move slot machines and gaming tables out of sight.

By the early 1950s, local political leaders and law enforcement officials realized that the high-volume illegal gambling had a very dark side. Gangland-style murders were frequent, as mob bosses took out competitors or employees who were skimming the profits. Law enforcement agencies started cracking down, and within a decade most of the illegal gambling in Tarrant County had been wiped out.

By the early 1950s, local political leaders and law enforcement officials realized that the high-volume illegal gambling had a very dark side. Gangland-style murders were frequent, as mob bosses took out competitors or employees who were skimming the profits. Law enforcement agencies started cracking down, and within a decade most of the illegal gambling in Tarrant County had been wiped out.

For the next several decades, Texans who wanted to gamble legally had to take their business to Nevada. Finally, in 1987, the horse industry and gambling advocates again forced open the legal betting door in Texas. Pari-mutuel wagering at horse and dog tracks was approved by voters in 1987, and a Class 1 track went in at Grand Prairie, in Dallas County. To the west, a Class 2 track, Trinity Meadows, operated in Parker County for a time. Out of 15 horse track licensed by the Texas Racing Commission since 1989, seven never opened and three have shut down. Revenues at the three major tracks, including Lone Star Park, are down from a combined $129.4 million in 1999 to $93.8 million in 2008. In 1996, Texas voters approved simulcast betting at the tracks.

The Texas lottery started in 1992, and now includes a national Powerball drawing.

Indian tribes in other states have helped pull their people out of poverty by operating casinos for years, but Texas’ federally recognized tribes have had no such luck. Texas maintains that its anti-gambling laws supersede the sovereign status of the tribes, and federal and state courts have agreed.

The Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo tribe (also know as Tigua) near El Paso opened the Speaking Rock Casino in defiance of state law in 1993 and operated it until court rulings forced its closure in 2002. They’d love to re-open it if the state legalizes casino gambling.

“We still believe federal law supersedes state law, but that is a very complicated legal debate,” said the pueblo’s Gov. Frank Paiz. “The state has never had much of a relationship with us, and they sometimes forget we are even here. But we welcome being included in this legislation – and they need our support.

For casino supporters trying to pass legislation in Texas, the name of the game is economic impact.

“We have money going out of state that could stay here,” Menendez said. “The voters are in favor of more gaming options by a large margin. Jobs will be created, and we will be drawing more tourists and conventions.”

Carona said casinos are “not just about people coming in and playing blackjack or slots. We have looked at other states with these type of casinos, and less than five percent of the floor space is for gambling. There are hotels and restaurants and meeting space within the complex.

“Texas politicians have run away from this issue instead of dealing with it, and that is regrettable,” the Republican senator said. “In this case, the public is very much ahead of their elected officials.”

The Texas Gaming Association, a lobbying group for the resort casino gambling industry, paid for an independent poll of Texas voters last year, conducted by Wilson Research Strategies.

“Our research indicates that 68 percent of Texas voters would support a proposal to allow destination resort casinos,” said Chris Wilson, president of the polling firm. “This support extends across party lines with 75 percent of Democrats, 71 percent of independents, and 62 percent of Republicans.”

When Waco economist Ray Perryman studied the economic effects of gambling in 2004, he concluded that it would generate 90,000 to 120,000 new jobs, bring in $3 billion to $4.5 billion per year in new state and local tax revenue, and result in $45 billion in new capital investment and $51 billion in new economic activity annually.

Jack Pratt, 82, president of the gaming group, is a Dallas developer and former president of Hollywood Casinos, which operates 14 casinos nationwide and employs 18,000 people. He wants any Texas legislation to favor casinos over slots and video gaming at race tracks. “To do it right, you build them as a tourist and business destination,” he said. “Slots at racetracks don’t do that, and their presence makes it more difficult for the casino operators to make a profit.”

The 2009 bill, which his group helped write, would have set the tax rate for casinos at 15 percent of net profit, compared to 35 percent at the racetracks.

Pratt defended the discrepancy because of the extra tax revenue the casinos would generate via hotel rooms and eateries. “We need to work out a compromise with the tracks, but a higher tax rate for slots at the tracks will even the playing field,” he said. “The tracks won’t have the investment costs that the casino operators will have.”

“The race tracks came into the discussion wanting a monopoly for gaming,” he said. “But the studies have shown that the racino crowd comes mostly from a 50- to 60-mile radius. There is little economic benefit in that. We think it would be better if we had casinos that draw a higher quality customer who might be coming in from out of state.”

The Texans for Economic Development lobbies on behalf of dog and racetracks as well as horse breeders and trainers. Their view is that gaming at tracks in Louisiana and other states is pulling the horse breeders and bettors out of Texas.

“Tracks out of state are able to offer higher purses because of the slot machines and video gaming, and the breeders are following that money,” said Mike Lavigne, spokesman for the group. “Our problem with the proposal is the disparity in the tax rate,” which he said “would just stamp out the horse tracks.”

Lavigne said the lower tax rate at casinos would allow those businesses to offer better odds and better hotel deals to gamblers. “We just want the ability to compete; in doing that we can help the horse breeding industry,” he said.

Gambling supporters expect the 2011 legislation to again allow only a limited number of gambling facilities. But some observers question whether even a small number of big casinos and racinos could oversaturate the gambling market. Even before the current recession, hotel occupancy rates and gambling revenues were dropping in Las Vegas. In most areas, gamblers now don’t have far to go to place a bet: 42 states have legalized some form of gambling.

The 2009 bill would have permitted four gambling developments in North Texas – two casinos in Dallas County, one in Tarrant County, and slots and video gaming at Lone Star Park, also in Dallas County. It’s not a prospect that casino owners in Oklahoma and Louisiana find reassuring.

The 2009 bill would have permitted four gambling developments in North Texas – two casinos in Dallas County, one in Tarrant County, and slots and video gaming at Lone Star Park, also in Dallas County. It’s not a prospect that casino owners in Oklahoma and Louisiana find reassuring.

“It is a big state, with a lot of very large markets, and the casino industry has long seen Texas as the last place for big expansion,” said Michael Paladino, a gaming industry analyst for Fitch Ratings. “But this would not be very good for gaming in surrounding states that bring in the Texas money, and some of these companies with gambling in Louisiana and Oklahoma and even Nevada would be very exposed to a loss of income. But they would more likely be looking at how to participate [in Texas gaming], given the big market.”

The Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma operates the very successful WinStar World Casino just across the Red River from Texas, and they draw bettors primarily from the Metroplex. An economic subsidiary of the tribe – Global Gaming Solutions – put in a bid for Lone Star Park after the track owner filed for bankruptcy last year. Approval of that bid is expected by the Texas Racing Commission sometime in June.

WinStar would definitely lose a lot of business if the three destination casinos were approved for North Texas. But the tribe might be able to balance those losses with revenues from slots at Lone Star Park.

“Gaming in Texas is illegal at this point, and we’ll address that when and if it arises,” said Kim Koch, a spokesperson for Global Gaming Solutions. “Global Gaming is committed to making Lone Star Park a success, and to that end the company will support whatever the horse owners at that track are supporting.”

If the moral opposition to gambling has faded somewhat around the country, skepticism at the industry’s economic promises has grown.

When Lone Star Park was proposed in the early 1990s, Grand Prairie voters approved a half-cent sales tax to help pay for the facility. Backers said hotels and fine dining establishments would surround the race track, but that hasn’t happened. Track operators blame that on their inability to offer slot machines.

Casino gambling also hurts local businesses, according to several studies. When Atlantic City, N.J., began offering casino gambling in 1977, the city had 48 independent restaurants. Two decades later, there were just 16 left. A bank industry study concluded that bankruptcy rates in U.S. counties with casinos were 18 percent higher than in those without casinos. And a recent survey of Gamblers Anonymous members found that 57 percent admitted stealing to finance their gambling.

There is no question that gambling options have a social cost. Baylor University economics professor Earl Grinols has been researching the costs of gambling since 1991. His book, Gambling in America: Costs and Benefits, was published in 2004.

Grinols estimates that 30 to 50 percent of gaming operators’ revenue comes from problem or pathological gamblers. He also found that 80 percent of the revenues come from slot machines, the most addictive form of gambling. Not surprisingly, the addicts tend to live close to the casinos, meaning it’s the local communities that end up footing the bill for resulting problems.

The costs of gambling far outweigh the benefits, Grinols said. When factoring in a higher crime rate, social services costs, anxiety and depression, child neglect, and domestic violence among problem gamblers, governments will spend three dollars on gambling-related problems for every dollar they bring in in tax revenue and economic activity, he estimated.

“In case study after case study for so many years now, every researcher is finding that these casinos and slots at racetracks never fulfill the promises made by these gaming companies,” Grinols said. “The proponents of gambling always try to sell it as free money, but the opposite is true. We see damage to the communities close by these casinos, and Texans really have to think about whether they want that.”

Suzii Paynter is director of the Texas Baptist Christian Life Commission. Her organization has lobbied hard against gambling and will continue the fight in the next legislative session. “Typically, people assume we are against it from some religious, moral angle, but that is not the case,” she said. “We oppose it from the return-on-investment angle.”

Paynter said communities get an early return based on construction jobs as the casinos are being built. But after the casinos are up and running, “the destruction of the community around them starts. Gambling debts lead to embezzlement and other criminal behavior. A few people profit, but a lot of people lose, and sometimes they lose their home because of gambling.

“People always point to the money going out of state from gambling,” she said, “but I wouldn’t say the economies of Oklahoma and Louisiana are better off than Texas. We are much healthier economically, and we don’t have gambling.

“If they want to call gambling another harmless option for entertainment, they don’t know basic economics,” Paynter said. “People only have so much disposable income for entertainment. When casinos come closer to where they live, many take the money they might have used to go out to eat or to a sporting event, and they give that money to the casino. Local businesses lose out in the long run.”

John Kindt, a professor of business and legal policy at the University of Illinois, agreed that gambling actually hurts local economies. He pointed out that two states with serious economic problems – California and Illinois – have expanded gambling greatly in the past decade.

John Kindt, a professor of business and legal policy at the University of Illinois, agreed that gambling actually hurts local economies. He pointed out that two states with serious economic problems – California and Illinois – have expanded gambling greatly in the past decade.

“What happens is that gambling cannibalizes the economy,” Kindt said. “Economies grow when consumer spending increases. Gambling takes away from that. If it is in their backyard, people gamble more and more. If you want more bankruptcies in your area, bring in gambling. If you want more drug addiction, bring in gambling.

“Just because your neighbors have a nuclear waste dump in their backyard, doesn’t mean you want to do that too,” Kindt said. “This is being driven by special interests who want to take the everyday working man’s money. They want fresh gamblers, and they want to get them in Texas.”

Pratt dismisses most of the claims of high social costs and low economic benefits that the gambling opponents point out. “Problem gamblers make up just a little more than 1 percent of all the people who gamble at casinos,” he said. “There are ways to deal with that.”

When Nebraska was debating whether to legalize gambling in 2004 – to try to keep the money from going into riverboat casinos in Iowa – Omaha resident and multi-billionaire investor Warren Buffett worked hard against it. Nebraska decided against expanding gaming options.

“If you take a million people, … some number are going to change their circumstances dramatically for the better, but you’re going to have the other 999,000-plus who are going to lose the ability to take their families to a movie, to buy a toy for their kid, or worse yet, become an addict and lose everything they have including their self-respect and break up their family,” Buffett said at the time at a press conference. “I just think that’s a terrible trade-off.”

It’s anybody’s guess right now what this year’s elections will do to a gambling bill’s chances of success. The Tea Party movement might result in a more Christian-oriented conservative legislature – or in a more Libertarian-leaning body willing to consider gambling.

“The primary elections this spring in the House and Senate will have some bearing on this,” Burnam said. “If the Tea Party candidates get 25 to 30 percent of the Republican primary votes, then the elected Republicans may bow down to conservative pressure and vote against the gambling bill. But then again, they might see the movement as being more Libertarian, and they will cater to that crowd.”

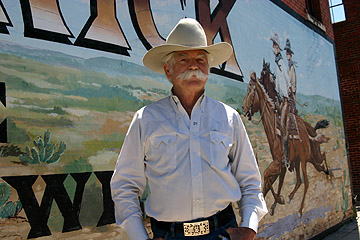

Hickman, the Stockyards real estate developer who has pushed for a casino in the past, did not respond to an interview request for this story. But Steve Murrin, the unofficial “Mayor of the Stockyards,” did.

Murrin has mixed feelings on opening a casino near Billy Bob’s. “I went up to WinStar about six months ago, and I didn’t see one nice new car in the parking lot, just lots of Texas plates on cars with dents and bad paint jobs,” he said.

“I don’t mind seeing rich fools losing their money, but it not good for anyone to have poor fools losing theirs,” Murrin said. “The Stockyards would fit the criteria of where a casino might work, but there is definitely a downside to gambling.”

Back at Billy Bob’s before the Delbert McClinton concert Matt and Lorene Foreman of Abilene were feeding a few quarters to the slot machine. The couple doesn’t go to casinos in Oklahoma or Nevada, and their foray into honkytonk slots was merely “a way to waste time,” Matt, an oil-and-gas rig worker, said.

“I don’t gamble, mainly because I’m cheap and see it as a way to lose my car-wash money,” he said with a laugh. “But I think I would vote for [expanding gambling with casinos], because I’m in favor of people having the choice if they want.

“People are going to gamble anyway, so we might as well keep the money in the state and use it for education and building better roads,” he said. “But I know this much: If they had casinos in Texas, I wouldn’t be going to them. They aren’t going to get my money.”