Local fans of the late suspense writer Patricia Highsmith should probably forgive the fact that the author hated her native Fort Worth. The list of people and things she reviled was long and included Jews, African-Americans, Arabs, food of almost every kind (she much preferred a meal of gin and cigarettes), the American publishing industry, and finally the United States itself. She also thought women were the inferior gender and voluntarily underwent an intensive and masochistic six-month psychoanalysis to rid herself (unsuccessfully, natch) of her lesbian orientation.

And what exactly did the celebrated author of Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley and its four sequels like? She adored the writing process, plentiful sex (she had a thing for married women), and literary murders. “Eccentric” is probably too kind a word for Highsmith, who was well aware of her own misanthropy – she once remarked that if she allowed herself to become human, life would be an unbearable experience.

And what exactly did the celebrated author of Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley and its four sequels like? She adored the writing process, plentiful sex (she had a thing for married women), and literary murders. “Eccentric” is probably too kind a word for Highsmith, who was well aware of her own misanthropy – she once remarked that if she allowed herself to become human, life would be an unbearable experience.

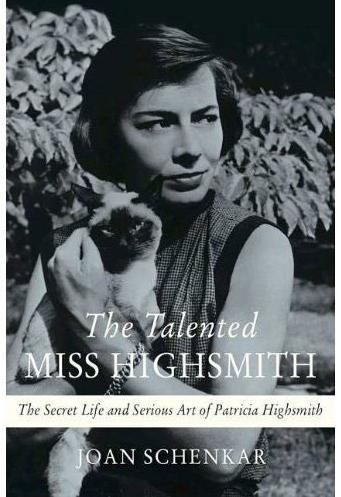

So it’s no small achievement that playwright-biographer Joan Schenkar is able to find perverse charm and consistent fascination in the messy, globetrotting life of Highsmith, who died in 1995 in Switzerland at the age of 74. At almost 700 pages, Schenkar’s The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith is a horse pill of a book. Despite the fact that Schenkar repeats her witty observations and restates the major themes of her subject’s life too often, the biography is juicy and articulate enough to sustain the interest of readers who have only a passing knowledge of Highsmith and her operatic obsessions and neuroses. Just when you think this notorious crime fiction writer has finally said or done something so nasty and vitriolic that you can no longer care about her, Schenkar steps in with a clever, authoritative interpretation that puts Highsmith’s self-destructive tendencies into the context of her grim, piercing, highly original novels and short stories.

Fort Worth plays a relatively small part in The Talented Miss Highsmith, but its appearances tend to be pivotal: Highsmith was born here in 1921 in her grandmother’s boardinghouse at 603 W. Daggett Ave. over near Hemphill Street and West Vickery Boulevard. Her father, who abandoned the family shortly after Patricia was born, drew cartoons for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. (Highsmith herself had an early career as a writer of comic book scenarios, which she later tried to hide to keep her literary reputation pristine.) Her moody and flamboyant mother, Mary Coates, remarried when “Pat” was 6, and the trio relocated to New York City, where mom and stepdad hoped to become graphic artists.

Mary’s career in commercial art – as well as her marriage – eventually fizzled, and she returned to Fort Worth after Pat graduated from Barnard College. Soon Pat began navigating the lesbian literary circles and drag clubs of the New York underground circa the late 1940s and early 1950s and reveling in the great critical acclaim that followed Strangers on a Train. (Alfred Hitchcock filmed it a year later.)

Her early success didn’t exactly instill pride in her competitive mother, however. As Schenkar illustrates with squirmy detail, Mary and Pat were always the most important person in each other’s life, and not for the better. If you want an example: Both mother and daughter made a cocktail-party anecdote out of the fact that a pregnant Mary had tried to abort Pat with a downed glass of turpentine. In a lifetime of bilious and occasionally violent exchanges, neither could forgive nor forget the other. In interviews for the book, Fort Worth native Tommy Tune expresses surprise at mother Mary’s dark side. He met her while he was performing in area productions and considered her to be a sweetly theatrical Auntie Mame type given to extravagant hand gestures with a cigarette holder during conversations. (Mary Coates died in a Fort Worth nursing home in 1991).

There was nothing sweet about Patricia Highsmith, an alcoholic dominated by compulsive behaviors who moved restlessly from the United States to England, France, and, finally, Switzerland. Even while her mother was alive, she described herself as an orphan on a perpetual journey to an elusive home. European readers and critics loved her, but upon her death in 1995, no U.S. publisher had purchased the rights to her later books. Given that her biggest hero may have been one of her own creations – the orphan Tom Ripley, that ingratiating master of disguises who murders easily and out of his own warped sense of ethics – it was pretty clear that Highsmith suffered from a terminal case of grievance toward the world. The Talented Miss Highsmith benefits greatly from its ironic, funny, conversational tone and an endless patience with Highsmith’s vices and venom. Schenkar invites us to marvel at her subject’s diamond-cut prose style and ultimately sympathize a little with the enormous unhappiness that went into her art.

The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith by Joan Schenkar

684 pps.