The ingredients of Steve Doeung’s life do much to explain why this soft-spoken, bespectacled man is the last holdout on Carter Avenue. After everyone else has given up, Doeung continues to resist Chesapeake Energy’s attempt to claim the majority of his front yard for a 16-inch pipeline that would transport non-odorized and highly flammable natural gas. He worries about his young daughter playing in the yard above a type of pipeline that has been known to explode when ruptured or leaking. He expects the value of his property to plummet and wonders if he could ever sell his house if he decided to move.

And most of all, he doesn’t like being manipulated by a corporation out to multiply its millions.

And most of all, he doesn’t like being manipulated by a corporation out to multiply its millions.

Countless memories, even some that seem inconsequential, bounce around in Doeung’s head and help shape his decisions while he navigates this minefield of law and bureaucracy.

For instance: the image of Davy Crockett in The Alamo, battling his enemies even after he was out of bullets. Recollections of that movie are one reason why the Cambodian-born Doeung wound up in Fort Worth.

Doeung’s father packed up the family in early 1975, shortly before the Khmer Rouge began its long reign of terror and genocide that cost the lives of more than 2 million Cambodians. Many of Doeung’s relatives would be counted among those casualties. “It scarred my mother pretty bad,” Doeung said. “I don’t think she ever got over it.”

The family stayed in a refugee camp in Thailand for six months before immigrating to the United States. After a brief indoctrination at a U.S. Army camp in Arkansas, the Doeungs and other refugees had to decide where to settle.

“Most people chose California or Florida because of the similarity in climate [to Cambodia],” Doeung said. “I remember people laughing or being baffled about my father’s decision to go to Texas. But a few years earlier he had watched The Alamo, with John Wayne. There was something about that movie and the spirit of the people that really stuck with him.”

The Fort Worth-Dallas region was booming, and the Doeungs decided it was a good place to make their stand. In December 1975, a local church leased a small apartment on East Lancaster Avenue for Sokthy Doeung, his wife, Banan, their five children, and a longtime family servant. Sokthy got a low-level job at the city parks department. They all struggled to learn a new language and fit into an odd, citified cowboy culture that didn’t really know what to make of this family, perhaps the first Cambodian refugees to light here.

Steve Doeung was 10 when his family made the move. He learned to deal with bullies and racists, excelled in sports, hit the schoolbooks with diligence, and made new friends. He went on to earn graduate degrees in psychology and Christian studies at a Houston college, then put himself through Southwestern Baptist Seminary in Fort Worth, with plans to become a minister.

But a missionary trip to Minnesota in 1986 left him feeling ill. Since then, chronic fatigue and aching muscles have forced him to give up the idea of the ministry. Many years passed before a doctor diagnosed him with Lyme disease, a tick-borne ailment that, if left untreated, can evolve into a debilitating malady. He receives treatment now, but the physical damage is done, and the pain and other symptoms continue.

His faith helps him cope. That same faith, combined with the stubborn independent streak implanted by his adopted state, has strengthened him while he’s done what few people considered possible: put up a thus-far effective fight against a powerful industry and complicit city officials.

His supporters say Doeung displays bravery not unlike that shown by those who stood up to the Mexican army at the Alamo in the fight for Texas independence.

“It’s not about the money with Steve, it’s about the principle. That’s about as courageous as you can get,” said Gary Hogan, who served on the city’s gas ordinance task force and saw first-hand how difficult it is to stand up to gas companies and their teams of lawyers.

Chesapeake revealed plans to purchase pipeline easement rights from Carter Avenue residents in spring of 2008, setting off a pitched battle with homeowners who didn’t like the idea of a 16-inch gas line – big enough to swallow a beach ball – being buried underneath their front yards.

The company originally sought an easement 30 feet wide for a 24-inch-diameter pipeline. That meant entire front yards would be claimed. Amid howls of protest, the easement was narrowed to 20 feet and the proposed line reduced to a 16-inch diameter.

Texas Midstream Gas Services, a Chesapeake subsidiary, wants the easement for a line to carry gas from a well near Carter Avenue. Easements give workers access to properties, and they can dig up the pipelines when they wish or even add more. Meanwhile, homeowners are limited in what they can put on easement surfaces. In other words, your front yard is no longer yours.

Energy companies years ago determined that their pipeline subsidiaries could claim the right of eminent domain, as utilities or “common carriers.” They can force owners to sell easements on private property, even if other easements owned by other companies are available nearby. The practice has drawn vehement criticism from property owners, rural and urban, across the state, and critics say the companies abuse their eminent domain powers to take more land than is often necessary.

For instance, Chesapeake has begun discussions with Texas Department of Transportation about sharing an already established easement near I-30 instead of putting the pipeline down Carter Avenue. (TxDOT had opposed running the pipeline along the freeway but later withdrew its objections.) But the discussions didn’t start until criticism by Carter Avenue proponents reached a fever pitch. And there is still no word on whether Chesapeake will use the I-30 easement even if it’s offered.

Texas Midstream referred questions for this story to a Chesapeake spokesperson who didn’t return a reporter’s calls.

Bruce Waterman, an engineering assistant at the Texas Railroad Commission who processes pipeline permits, acknowledged that gas companies’ creation of pipeline subsidiaries as a means to claim eminent domain powers involves “some gray areas.

“The rules are completely written for the gas companies,” he said.

It’s a bitter pill to swallow for property owners whose land ends up helping build the fortunes of gas companies while their own property values and quality of life may plummet. Chesapeake, for instance, reported a net income of more than $600 million in 2008, and CEO Aubrey McClendon received a $110 million pay package in 2009.

The battle on Carter Avenue was prefaced by Chesapeake’s decision to bulldoze a hill and remove trees near the Tandy Hills Natural Area to prepare for the so-called Thomas Well a block away on Scott Avenue. The company hadn’t received its well permit but started preparing the site anyway. The city council later approved a permit, and the well was drilled in September 2008.

Many residents favored the permit, especially those along Scott Avenue who would earn royalties without having to relinquish 20 feet of their yards. They gladly leased their mineral rights and easement rights and looked forward to mailbox money. Others resisted. They wondered whether small royalty checks would be worth enduring big trucks coming and going through the neighborhood’s narrow streets. Some fretted about safety and environmental issues and property values. People who wanted to move away doubted they could sell a house slated to lose most of its yard to a pipeline easement.

Many residents favored the permit, especially those along Scott Avenue who would earn royalties without having to relinquish 20 feet of their yards. They gladly leased their mineral rights and easement rights and looked forward to mailbox money. Others resisted. They wondered whether small royalty checks would be worth enduring big trucks coming and going through the neighborhood’s narrow streets. Some fretted about safety and environmental issues and property values. People who wanted to move away doubted they could sell a house slated to lose most of its yard to a pipeline easement.

“That [Thomas] well never should have been drilled,” said Tandy Hills Natural Area activist Don Young. He legally parked a vehicle along Scott Avenue to disrupt the flow of gas trucks during the drilling, earning him the anger of drillers and Fort Worth police, who couldn’t convince him to move for several hours.

Hogan was a member of the city’s gas ordinance task force when Chesapeake first expressed interest in the Thomas Well. He and several other task force members insisted the area wasn’t conducive to drilling. The houses along Scott and Carter avenues are modest, but the neighborhood represents something that Fort Worth officials say they want and need – affordable housing enjoyed by a diverse mixture of immigrants, seniors, young families, and low-income residents.

Hogan urged the task force to stiffen the drilling ordinance to protect these types of neighborhoods. The task force, weighted heavily with industry insiders, ignored the pleas.

Chesapeake’s Hickman Well is near I-30 and Beach Street, about a mile from the Thomas Well. Once those wells were drilled, Chesapeake wanted to connect them with a pipeline and announced its plans to place the bulk of the lines under the Carter Avenue yards rather than in the I-30 easement overseen by TxDOT or along Scott Avenue, with its many commercial properties.

“Chesapeake knew the pipeline would have to go through,” Hogan said. “It’s an affront to me that this was chosen as a well site. It was totally unreasonable.”

Still Chesapeake cajoled, connived, threatened, and eventually secured most of the properties it needed. Homeowners who resisted faced condemnation hearings and fights waged by lawyers in county courtrooms. Texas Midstream filed petitions for condemnation against a half-dozen homeowners. One by one the holdouts folded, all except for Doeung.

He refused Chesapeake’s offer of $4,622 for his front yard. Texas Midstream filed a petition for condemnation against him on Aug. 21, 2008, and a hearing was scheduled for October.

But persistence and cleverness have allowed the cash-strapped Doeung to hang onto his property for a surprising 17 months despite the fact he has had to represent himself against Chesapeake’s team of lawyers in two hearings.

Doeung filed a court petition of his own, accusing Chesapeake of failing to follow proper procedures in notifying him of the condemnation effort. Chesapeake and the pipeline remain at a standstill.

“Steve is going to stand on his moral principles, [maintaining] that this is wrong what they are doing,” Hogan said. “He hasn’t been able to hire his own attorney, but he’s a bright guy and has done enough research to attempt to represent himself.”

Hogan’s admiration doesn’t mean he is convinced Doeung will prevail.

“Chesapeake is too powerful for its own good in this city, and they are highly politically connected,” he said. “Chesapeake gets what they want.”

Maybe. Chesapeake and its pipeline subsidiary might be masters at manipulating the legal and political systems, but the resourceful Doeung has stood to toe-to-toe with them and has exploited a few loopholes himself.

January’s arctic winds chilled a recent afternoon but didn’t deter Doeung’s 7-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, and his wife, Teresa Davis, from playing kickball in the front yard. Their playground is where Chesapeake envisions a pipeline easement. The idea of a private business forcing him to accept a 16-inch pipeline buried underneath his daughter’s feet just doesn’t seem right to Doeung.

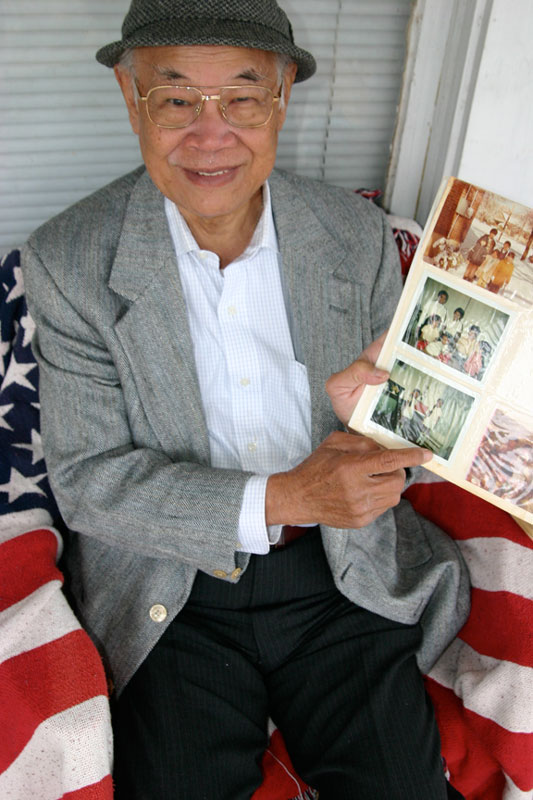

On the porch, Doeung’s father, Sokthy, sat on a chair draped in an American flag. He alternated between watching his granddaughter play and leafing through a scrapbook filled with old photos.

“This was in Thailand,” he said, pointing to a black-and-white photo that showed his entire family standing in front of the tattered tent where they lived briefly after fleeing Cambodia.

Sokthy Doeung was a college president in 1975, educated and wealthy. But when Pol Pot’s murderous regime took over Cambodia, education and wealth could get you tortured and killed – or at least forced into agrarian labor and “re-education” camps. Sokthy hustled his family out of the country on a small boat, leaving most of their possessions behind.

“I just wanted to save our lives,” he said. “If I would have stayed, I wouldn’t have lived.”

His wife, Banan, didn’t want to leave behind most of her jewelry and possessions, but he told her they had to flee quickly and travel light. Yet he insisted on carrying a highly unlikely possession with them – a set of encyclopedias wrapped in plastic and packed in boxes.

Sokthy wanted his children to see how important an education was. The burden of the encyclopedias “was symbolic,” he said. And it worked.

“That really made an impression on all his kids,” Steve Doeung said. “There was never any issue of us not finishing high school or college. All except one of his children have graduate degrees.”

Of the 40-odd books they packed, transported, stored with acquaintances, and later had shipped to the United States, less than half survived. Sokthy still has them. In Texas, Sokthy sold encyclopedias door to door for several years. His story of moving his own encyclopedias halfway around the world helped him sell more than a few sets, he said.

Seeing his son fight against a powerful energy industry intent on taking his property makes Sokthy proud, but worries Banan.

“I’m real scared,” she said. “They might take him away.”

Steve Doeung isn’t worried about being “taken away.” He still considers American the land of the free and the home of the brave. But he understands that fighting for his rights can pose problems. He’s spent hundreds of hours researching condemnation laws, writing letters, and representing himself in hearings.

And he’s felt heat from the city. He and some of his supporters don’t think it is a coincidence that Fort Worth code enforcement officers have paid him so much attention lately. He’s received citations for building materials stored on his porch and in his backyard.

“It would appear Steve is also fighting the city,” said Louis McBee, an Eastside activist and organizer with Fort Worth Citizens for Responsible Government. “I’ve been by his house, and I don’t see any [code] problems.”

The neighborhood was undergoing a renovation with help from the city at about the same time Chesapeake was seeking easement rights. Street repairs and new sidewalks gave some polish to the old neighborhood, and residents were encouraged to tidy up.

Still, Code Compliance officers and police had never bothered Doeung prior to the condemnation dispute, he said. Code officers showed up for the first time just weeks after Doeung began fighting Chesapeake. Afterward, he began getting warnings for code violations. Doeung, McBee, and others wonder if city officials are flexing their muscles on Chesapeake’s behalf. After all, the city has the ultimate power over the pipeline – city approval is required since the lines would run underneath city streets.

“Five of the nine members of the Fort Worth City Council will have to give Chesapeake permission to cross under those four or five streets,” Rep. Lon Burnam said.

City council members, led by oil-and-gas proponent Mayor Mike Moncrief, have favored gas companies on almost every decision since the Barnett Shale play began five years ago. In Doeung’s eyes, the city and Chesapeake are working in tandem to make the pipeline easement happen.

“It would appear the Code Compliance office is being used to harass Steve and his wife,” McBee said.

Doeung said his daughter cried when numerous code officers and Fort Worth police officers showed up at the family’s doorstep on July 2. Doeung described it as “a raid” and said police were aggressive and stern.

Doeung’s yard is more cluttered than those around him, but his property doesn’t appear to be rundown or neglected. When he got his first warning in November 2008 for keeping things like building materials on his front porch, he moved the material to a storage shed and thought the problem was solved. But he was warned twice more, he said, because he had moved some of the supplies back onto the porch because he was intending to use them soon.

City spokesman Bill Begley said Doeung and his wife weren’t the only Carter Avenue residents to be scrutinized last year.

“More than 50 complaints were investigated on Carter Avenue in 2009, resulting in 39 cases being initiated for enforcement action,” Begley said.

As for the “raid” that Doeung described, senior Code Compliance officer Jim Britton said it is not uncommon for police and code officers to work together during inspections.

Doeung is upset by these intrusions but typically maintains his calm. Time and again he has relied on his past to guide his actions. He recalls what it felt like to be uprooted from a charmed existence in Cambodia and suddenly find himself in a refugee camp.

“It was confusing and scary and somewhat humiliating to be destitute,” he said. “It was especially tough for my mother because she had always had a pretty privileged life. My father channeled his energy into helping other refugees settle in.”

Barbed wire and armed guards encircled the camp. Doeung, being the oldest of five children, would sometimes sneak out and do menial labor at nearby boat docks for spare change to buy food.

“They spoke a different language than I did, so I got yelled at a lot,” he said. “But it didn’t kill me. It made me stronger.”

After the family arrived in Fort Worth, the family converted to Christianity and found sponsors at Sagamore Hill Baptist Church to help them settle into their new life. Sokthy, the former college president with a master’s degree, could find only various unskilled and low-paying jobs at first. Later he became a church pastor.

Doeung, like his four siblings, adjusted to a new school, language, and culture in Texas.

“Everything was so big – not just the buildings and space but the people,” he said. “Everyone was so much taller and bigger.”

The kids had to get accustomed to drinking milk, a staple in Texas schools but not in Cambodia.

“We drank milk because it was part of the school meal, but we weren’t used to it,” he said. “The bus driver was glad to get rid of us because every day one of my siblings would throw up on the way home.”

After a short stay in an apartment, the family moved into a rent house near Carter Avenue.

“We were the only Cambodian family here for four or five years,” he said.

His parents forbade him to play sports, but he rebelled. The family was going through cross-culture shock, with his parents rooted in the old ways and the children embracing the new. Doeung applied himself to his studies to please his father but also tried out for volleyball, softball, and other sports teams, paving the way for his younger siblings.

“That was probably the first cultural clash between me and my parents,” he said. “But all of us earned varsity letters in sports. I told my parents early on that I wanted to be an American. I love this country, even though it took me until my junior or senior year before I could feel comfortable enough to say ‘my country.’ Once we were here, this was home.”

Racial comments were common. Kids once threw rocks at Doeung. And the family’s car was set on fire in the driveway one night. Doeung was scared but angry. He wanted to find the arsonist and press charges. His parents, however, told him to ignore it. “This is not our country,” his father said.

Racial comments were common. Kids once threw rocks at Doeung. And the family’s car was set on fire in the driveway one night. Doeung was scared but angry. He wanted to find the arsonist and press charges. His parents, however, told him to ignore it. “This is not our country,” his father said.

Doeung recently told his daughter the story about the burned car, but he added a different message at the end: “I told her this is our country, this is our community.”

Mostly, though, neighbors and school chums treated the family warmly, he said.

After graduating from Eastern Hills High School in 1983, Doeung attended Houston Baptist University on an academic scholarship. Next came the seminary. He wanted to follow his father into the ministry. But he’d begun having physical problems from undiagnosed and untreated Lyme disease. Every day he awoke to flu-like symptom and couldn’t figure out why.

“I was always healthy, didn’t drink or smoke, and was always athletic,” he said. “I just kept pushing myself.”

He began teaching at an alternative school aligned with Trimble Tech High School in the mid-1990s and purchased a home on Carter Avenue near the old rent house where his family had once lived. But in 1998 he hit a wall.

“That’s when my body just crashed,” he said. “I woke up one morning and have never been the same since. I felt like my body had been beaten up by two-by-fours. Head, eyes, spine. It was horrendous.”

Few Texas doctors were familiar with Lyme disease back then, and when nobody could diagnose his ailments, Doeung became depressed. He saw a psychiatrist and took mood-altering drugs. He lost his job and health insurance and struggled with money.

In 1998, he and his longtime girlfriend, Teresa, stood before a Tarrant County justice of the peace and got married. For their honeymoon, they went home and ate fried Spam, then drove to Arkansas to see the fall colors.

A doctor finally diagnosed chronic Lyme disease two years ago. Doeung has received treatment, but the flu-like aches and pains and the sleepless nights haven’t abated, he said.

For the past 10 years, Davis has worked full time to pay the bills while Doeung takes care of the house, including caring for the couple’s daughter, born in 2002. And that’s where Doeung’s life was hovering until Chesapeake came along and decided his front yard would make a good place for a pipeline.

After filing a condemnation petition against Doeung in August 2008, Texas Midstream asked Tarrant County Judge Vincent Sprinkle to appoint an ad litem attorney. The company couldn’t track Doeung down but was eager to get the condemnation process started. Chesapeake paid an ad litem attorney $1,692 to represent Doeung in the court hearing.

At the time, Doeung and his family were staying in two places: the Carter Avenue house and an apartment on the West Side. The couple wanted their daughter to attend a school on that side of town and had established residence there. At the time, Carter Avenue was undergoing a renovation, with new streets and sidewalks, and the dust disturbed his daughter’s allergies.

Still, Doeung said, they continued to spend considerable time on Carter Avenue and received mail there. He said he never got any notices about the pipeline and doesn’t understand why Chesapeake considered him difficult to find. (Doeung was also difficult to contact during the research for this story. He missed several appointments with Fort Worth Weekly, explaining later that he had been ill or had misplaced his cell phone.)

He said he first heard about the pipeline after reading a Fort Worth Star-Telegram article that mentioned his next-door neighbor, Jerry Horton, and referred to Doeung as an absentee owner.

There was a problem with Chesapeake’s claim on Sept. 4 that he couldn’t be found – Doeung had corresponded with company spokeswoman Julie Wilson a month earlier.

“The Star-Telegram put her contact info in the article,” he said. “I wrote her a brief e-mail saying I heard about this and that I wanted to make sure this was my street being affected because I had not gotten anything from them. I didn’t hear anything from her office, but three days later somehow a UPS express envelope was delivered to my front door at the house. In there was a letter from the guy in charge of Texas Midstream.”

The letter said Texas Midstream had tried and failed to contact him after numerous attempts and the company was giving him a final chance to accept the offer for his property or face condemnation.

“First I had to clean out my eyes,” he said. “I had to read it over again. I couldn’t believe what I was reading. I got mad.”

In Doeung’s eyes, he was being threatened and called a liar. He paid a visit to a Texas Midstream office and hand-delivered a written rebuttal. The next week, a car pulled up to his curb and a well-dressed man and woman got out.

“I was working on the porch,” he said. “They identified themselves as representatives of Texas Midstream and said they were so surprised to see me because they had been looking for months for me.”

They wanted him to sign a document. He asked if he’d need a lawyer to look it over since he was under threat of condemnation. The Midstream representatives, one of whom had a notary stamp at the ready, told him it wasn’t necessary, he said. They described the well sites, proposed pipeline route, and the contract and promised him a check that same day.

At the time, Texas Midstream had already filed its condemnation petition.

At the time, Texas Midstream had already filed its condemnation petition.

“I resented that,” Doeung said. “To me, I just saw somebody pull out a gun, in a way, and I heard it being cocked. You’re telling me if I will just accept this, you will put the gun away. Looking back, eminent domain is not really like a gun – it’s more like a tank.”

Doeung said he wanted time to examine the contract. A rep called him a few days later, and Doeung asked questions, such as why the pipeline was running down Carter Avenue instead of Scott Avenue.

“He said it was to minimize environmental impact, that the environment was a big concern,” Doeung said. “I wasn’t buying it.”

The money offered for the easement didn’t seem fair to Doeung, since a few thousand dollars wouldn’t compensate for reduced property values or lost peace of mind. He suggested that Chesapeake buy his house and allow one of its managers to live there and raise a family and prove to everyone how safe it is to live next to a pipeline. Texas Midstream wasn’t interested in buying his house but upped its offer from $3,800 to $4,800. Negotiations broke down.

To Doeung, the whole process stank. He saw how people who signed up early and cooperated with the gas company got low-balled, and those who fought back got bigger offers. Doeung’s next-door neighbor, Jerry Horton, got $15,000

“I had talked to a neighbor who didn’t speak much English, and he was lied to and tricked into signing for $1,500,” Doeung said. “They told him he was one of the last people to sign the easement contract and that they have eminent domain power to sue him. I don’t care who you are, if you hear the words ‘getting sued,’ it makes your heart skip a beat. That’s abusive and a threat. The bullying, the arrogance, the tactics they use to do this to people – it was offensive. I wanted to expose those dishonest and unconscionable tactics.”

Two court appearances and almost two years later, he’s still fighting and still trying to expose a system that seems unfair and predatory. He’s managed to buy so much time by catching Chesapeake in an apparent slip-up. He said the company filed for condemnation and had an ad litem attorney appointed because they allegedly couldn’t find him.

“I typed up a petition and ran to the courthouse and went to the clerk’s office and filed my petition and pointed out that their lawsuit is based on false information and that it should be tossed out,” he said.

At his first hearing in Sprinkle’s court, he asked for a court-appointed attorney but was refused. Condemnations are civil rather than criminal affairs, which means there is no mechanism to provide an attorney for someone who can’t afford to hire one. Sprinkle gave him 30 days to find representation. Doeung later announced he would represent himself. Then an attorney agreed to help and asked for an extension. Then the attorney became ill and dropped out.

In December, Doeung appeared in Sprinkle’s court and said his attorney wasn’t answering his calls and so he was back to representing himself. Don Young attended both of Doeung’s hearings and marveled at how Doeung has held off the numerous attorneys representing Chesapeake. “Steve’s maneuvering has kept him going,” he said. “The others didn’t read their documents like he did. He has found errors he has been able to exploit.”

But the judge is becoming exasperated, Young said.

“Steve doesn’t want to talk about how much his property is worth. He wants to talk about the injustice, and he wants to make his voice heard, but the judge isn’t interested in that,” Young said. “He seems more irritated with Steve than Chesapeake, even though Steve hasn’t done anything wrong, and Chesapeake has made lots of errors.”

Hogan said it’s an open secret why Chesapeake won’t let the Carter Avenue condemnation die, even though the I-30 easement is now available.

“Chesapeake doesn’t want to set a precedent,” Hogan said.

After all, if one David can defeat the gas Goliath or fight it to a standstill, how many more might be inspired to try the same thing?