Lloyd Burgess owns the Lucky B horse farm in Denton County. He made a good living raising and boarding horses there from 1993 until 2006, good enough to pay for a $350,000, 45-stall barn a few years back. These days though, it’s not so lucky.

Everything changed for him in October 2006, when an explosion occurred at a gas compressor station just beyond the edge of his 30 acres. Burgess, who had been out of town, returned to discover that one of his mares had aborted her foal. Two weeks later, the same thing happened to a second mare.

Bad things just kept happening after that, on his farm in the oddly renamed town of DISH, just up the road from Justin. Several months later one of his stallions got sick and finally had to be put down. Then a mare went blind. Then another stallion, a valuable quarter horse, got sick and was saved only when a friend offered to take if off Burgess’ property, away from the compressor stations on Burgess’ back fence line, to nurse it back to health.

Bad things just kept happening after that, on his farm in the oddly renamed town of DISH, just up the road from Justin. Several months later one of his stallions got sick and finally had to be put down. Then a mare went blind. Then another stallion, a valuable quarter horse, got sick and was saved only when a friend offered to take if off Burgess’ property, away from the compressor stations on Burgess’ back fence line, to nurse it back to health.

That fence used to be lined by huckleberry trees, planted as a windbreak back in the 1930s and ’40s. The wind blows through pretty freely now, however, since most of the trees have recently died.

“After the explosion and what happened to my horses, all my boarders took their horses out of there,” said Burgess, now 56. “Who could blame them? This was going to be my retirement, but now it’s valueless.”

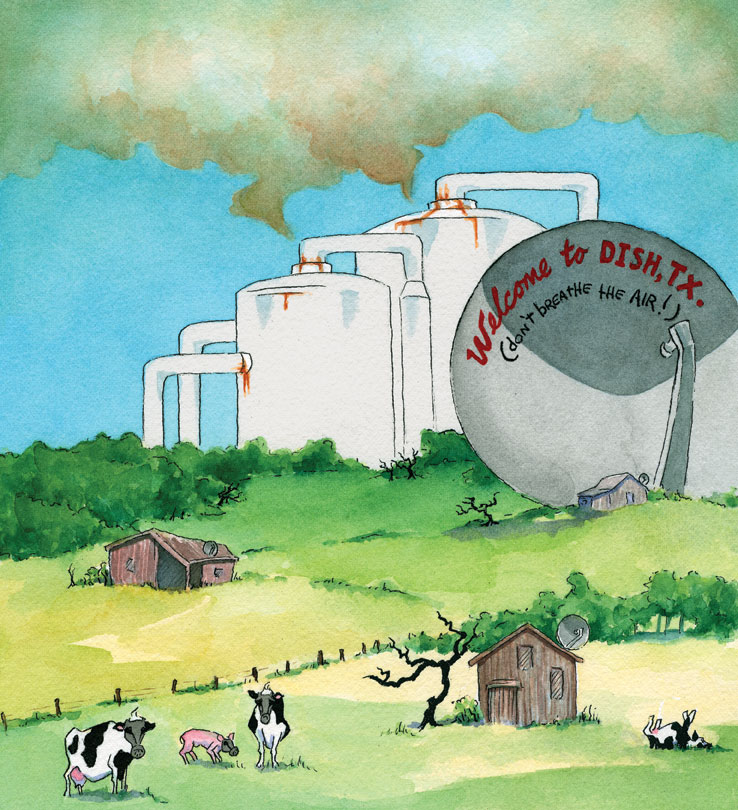

The words “valueless” and “worthless” come up a lot in conversation with people from DISH, the two-square-mile town that back in 2005 agreed to change its name from Clark in exchange for 10 years of free satellite TV service for all of its 180 or so residents.

The town is so small that MapQuest doesn’t recognize it. But the gas companies have certainly found it. Folks there say their town is under assault by the companies that profit from the Barnett Shale, their air fouled, their hearing attacked by ear-splitting noise that goes on for hours at a time.

In some places, opposition to the disagreeable and dangerous aspects of shale gas production is muted by the little royalty checks that residents get each month. Here, however, almost no one owns their mineral rights, so there is no “mailbox money” coming in to make them forget their troubles.

And those troubles, for the most part, aren’t with the gas wells themselves, 18 of which have been drilled in the town. The problem is that the gas industry has picked DISH and a few acres just outside its city limits as a perfect place for not one or two but eleven compression stations, to which gas is piped from wells all over northern Tarrant and Denton counties, to be treated, compressed, and sent out into bigger transmission lines. Residents say the veritable industrial corridor thus created emits hydrocarbons that kill trees, sicken and endanger animals and people, and are making their properties worthless.

What compressor stations require, of course, is pipelines, both the gathering lines coming in and the transmission lines going out. And those lines, residents say, are the gas industry’s second line of attack on their little burg. Pipeline companies have taken so much land, by eminent domain or the threat of it, that some farms have lost half their acreage. And whereas the compressor stations’ dangers are all too evident every day, the pipelines represent a hidden but no less potent threat, carrying billions of cubic feet of flammable, undetectable gas a few feet below the surface, in close proximity to houses, roads and schools, and even the town hall.

But the DISHers are beginning to fight back. Their first salvo was an air-quality study the town commissioned in August that showed high concentrations of cancer-causing chemicals and neurotoxins in the air near the compressor stations – what one researcher called “a toxic soup.”

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, in charge of monitoring air quality in Texas, has done nothing about DISH’s problems thus far. But now, both state and federal regulators say they may look into the situation.

“Think about it,” Mayor Calvin Tillman said. “We’ve got all that toxic waste pouring out into our town, then we’ve got all the potential danger from explosion. The pipelines under DISH and the compressors are each capable of moving a billion cubic feet of gas per day, so that on any given day we might be sitting on 11 billion cubic feet of gas. What happens if something goes wrong? The whole place will evaporate. And there have already been several incidents, including a lightning strike that started a fire. And at some point there is going to be a catastrophe. The gas companies have just sacrificed us.

“We’re going to do follow-up studies and we’re looking at all of our legal options,” he said. “Litigation is not out of the question.”

DISH is located just off FM 156, a few miles west of I-35 and Denton. It’s pretty much in the middle of nowhere, which, from the drillers’ point of view, made it the perfect place for gathering, compressing, and transmitting natural gas to and from all directions.

Though there had been some shale drilling in the area up to a decade ago, gas companies began to show up in force in 2005, taking land right and left for pipeline and road easements, land that many residents sold only under duress.

One of the hardest hit was Chuck Paul, who bought 64 acres for a horse farm in 2001. He works with civil engineers on the design of public street and utility projects. “There was one pipeline on my property when I bought it,” he told Fort Worth Weekly. That was near the property line, he said, and didn’t affect much. “My feeling was I’d start a horse ranch, but I’ve got a background in subdivisions, so if the economic boom ever got here, I knew I could sell it for a subdivision.”

But in 2006 a landman representing a company collecting easements for Energy Transfer Partners asked permission to survey his land for a possible future pipeline. A year later, “they said they’d decided to lay a line on my property … and said they’d pay for the easement.”

The pipeline was to take a 2,000-foot-long, 50-foot-wide swath out of his land, a little over two acres. But the company ended up taking multiple easements and leaving small strips of unusable land in between. In all, Paul lost the use of more than 30 acres.

Paul, like many North Texans faced with similar situations, wasn’t familiar with state and federal law governing pipelines. He didn’t know how easy it would be for the land to be condemned. “I didn’t think they could just take it pretty much at will, so I did the math and told them I’d sell them the easement for $30,000 an acre. They countered with $1,000 an acre.”

He wound up getting a bit less than $60,000 for the property needed for two pipelines and a road easement, leaving him with such a patchwork that he can now develop only about half his property. In effect, he believes he has lost most of the value of his land. “The gas companies pay a one-time fee for your land, but you lose the right to utilize it as anything more than grassland forever,” he said. “You can never build on those easements. They took my retirement away by eminent domain.

“They just screwed me. And they might want to come back and take more. And there’s nothing you can do to stop them. If they’d have paid me fair market value, I would have sold it to them. But with the right of eminent domain they have, well, they can do anything they want.”

“They just screwed me. And they might want to come back and take more. And there’s nothing you can do to stop them. If they’d have paid me fair market value, I would have sold it to them. But with the right of eminent domain they have, well, they can do anything they want.”

Though pipeline companies are private, federal law gives them the right to take property for pipelines through eminent domain. It’s a reality that sticks in the craw of property owners and one that state legislators have thus far found no way to change.

Losing the use of land is only one of the issues posed by pipelines. Gas running through gathering lines is generally filled with chemicals and water that corrode the pipes; it’s also generally unodorized until it reaches the compressor – which means people nearby won’t know they are in danger if a leak develops. Companies have mechanisms to alert them to weakening pipes, but leaks and explosions in the Barnett Shale have shown those systems aren’t foolproof.

Tillman said that when the pipeline companies first started seizing land in his town and the surrounding countryside, he tried to negotiate with them over location to minimize the problems. “But I quickly discovered that the gas companies just tell a city where they’re going to build, and that’s that,” he said.

At about the same time DISH’s inhabitants were losing their land to pipelines, the compressors began to arrive. The first one was erected in late 2005 just outside the DISH city limits, on a plot of about 11 acres owned by the Bennett family of Dallas.

Nobody in DISH liked it, but most folks figured one station would be it. Instead, however, “that first compressor station, built by Atmos Energy, was quickly followed by a second by Atmos, then two by Energy Transfer Partners LP and three by Enbridge Energy Partners LP,” Tillman said. Four more compressor stations – three belonging to Texas Midstream Gas Services (then a subsidiary of Chesapeake) and one belonging to CrossTex Energy LP – were built on a separate nearby property, also owned by the Bennetts, within the town limits

Tillman has tried to talk that family into voluntarily allowing DISH to annex the larger compressor complex. In that case, the city’s tough gas well ordinance would apply, giving residents more control over noise pollution and aesthetics. “We could at least make them house the compressors [put them in enclosed, sturdy buildings], which would lower the sound level, and make them put up a masonry fence if that land was annexed,” said Tillman. “Unfortunately, the family doesn’t want to do it. I just don’t think they care.”

Family spokeswoman Elsie Bennett said that, indeed, she wants to avoid city regulations.

“As soon as you go into a city, there are rules and regulations, and they start to tell you what you can do and not do, and we decided that for right now it would be better not to do that, ” she said. “Plus it’s another entity you have to pay taxes to.”

She seemed to have little understanding of how bad a situation the compressors have created in the town. “I can’t keep track of how many compressors are there without the papers in front of me,” she said. For instance, she said she thought all but one of the compressors were enclosed by buildings. In fact, only two of the seven compressors outside the city limits are enclosed.

At the sites themselves the noise levels are overwhelming. But even people who live several hundred feet away say their quality of life has been ruined.

“What first got me was the noise,” said DISH City Commissioner Bill Cisco. “You can’t sit outside and enjoy nature anymore with their loud noise and noxious fumes day and night, every day.”

Jim Caplinger lives a little over 800 feet from the edge of the out-of-town row of compressors but still finds the noise unbearable. “They tell me I can’t hear a thing because of how far away I am, but that’s nonsense. It’s like an amphitheater, and I’m at the center of a little valley coming to my place. And the noise is 24/7.”

He said it has essentially ruined life for him and his wife. “You don’t want to go to the front porch for sure because it’s so loud, and if you go to the back porch, well, the sound bounces off the trees out back and roars at you like a jet engine getting ready for takeoff – but one that never takes off, just continually roars. There is no enjoyment to living here anymore.”

Caplinger has sued all of the companies connected with the compressor stations over the noise. The suit has not yet come to trial.

The compressor stations also regularly release noxious chemical fumes. The acrid smell burns the throat and nose and sears the eyes. “Some days you can hardly breathe anywhere in DISH,” Tillman said. “And then the trees started dying, so we wondered what was actually in those fumes.”

Caplinger said that when he moved into DISH, his street “was lined with willows, and now they’re almost all gone. They just died. And I’ve lost three elm and hackberry trees as well.”

Cisco agreed that something very troubling is happening to the trees. “We’ve lost a lot of trees in DISH. And a number of them were cedar trees, which are almost impossible to kill. Those trees breathe just like we do, so when they start dying, you’ve got to pay attention,” he said. “They’re the canary in the coal mine for our air.” Thus far, dozens of trees in the little town and right outside it have died.

Eventually, the town commissioned a study by Wolf Eagle Environmental Engineers and Consultants LLC, of nearby Flower Mound, to assess the effects of the compressor stations on air quality. Alisa Rich, owner of Wolf Eagle, said the research she did in DISH showed her there’s little doubt that the compressor emissions are killing the trees.

Her credentials regarding the effects of hazardous chemicals on plant life are extensive. She worked as a researcher in a bioterrorism preparedness program organized by the UNT Health Science Center and funded by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “I was an air emissions specialist researching airborne pathogens – chemicals – that could be used to kill vegetation and livestock. And when I look at the trees in DISH and the wind patterns we saw in that area and the pollutants in those emissions, well, it’s no wonder those trees died,” she said. “There are heavy sulfide concentrations in that air – some of the trees even had a yellow sulfur dusting – that cause leaf blistering, which prevents photosynthesis.” Trees can’t survive without photosynthesis, she said.

That kind of industrial pollution is supposed to be covered by state and federal air quality laws. But don’t tell that to the folks in DISH.

That kind of industrial pollution is supposed to be covered by state and federal air quality laws. But don’t tell that to the folks in DISH.

For years Mayor Tillman and other DISH residents tried to get the Texas Railroad Commission, which is supposed to regulate the oil and gas industry, and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which is charged with protecting air quality, to pay attention to what was happening to their town.

“We knew something was terribly wrong,” Tillman said. But their repeated complaints to the state agencies fell on deaf ears. The agencies “basically asked the companies to investigate themselves,” said Tillman, “and they came up clean every time.”

Gas company representatives went to town council meetings and explained that the people were only smelling the odorant being added to the gas as it was compressed. “But people who live here found it overpowering. Some thought they would die from it,” said Tillman.

The mayor said the only action the gas companies took in response to the complaints was to order a gas leak survey by Apogee Scientific, Inc., in May. That survey found no serious gas leaks from the compressor stations.

“While they were conducting that study and we were awaiting the results, I got an anonymous phone call telling me that the study the gas companies had done was not the one we needed,” Tillman said. “What we needed, I was told, was a test that looks for 40 different toxins in the air.”

Following the tip, Tillman proposed that the city spend $10,000 of its $70,000 annual budget for that kind of testing, to be done by Alisa Rich’s Wolf Eagle company.. To Tillman’s surprise, he said, townspeople encouraged him to spend the money and get it done.

The Wolf Eagle study involved placing seven specially designed air-catching canisters at different points in DISH in a 24-hour period between Aug. 17 and 18. The samples were analyzed for volatile organic chemicals, hazardous air pollutants, and other substances.

According to their subsequent report, Wolf Eagle researchers found high concentrations of carcinogenic and neurotoxin compounds in the samples, including those taken near residences.

“We suspected it [the report] was going to be pretty bad,” said Tillman, “but no one thought it was going to be as bad as it was. It was shocking.”

According to an analysis of the Wolf Eagle air study done by chemist and microbiologist Wilma Subra, the air samples from DISH contained the kind of chemical cocktail that would have been expected near refineries. Subra, who has been studying oil and gas field waste since the 1970s, said the DISH air samples included varying combinations of the carcinogens benzene and trimethylbenzene; napthalene, which is considered a potential human carcinogen; carbon disulfide, which can be absorbed through the skin and affects the central nervous system and many other bodily systems; and xylene compounds, which are neurotoxins. Subra is a member of the board of Earthworks, a nonprofit group that works with communities to address the destructive impacts of mineral development.

At one location, the air sample contained benzene at 8.7 times the state-set level allowed for long-term exposure. Carbon disulfide was detected at more than 10 times the acute, or short-term, levels allowed by TCEQ regulations and more than 100 times what’s allowed by the long-term standard. Napthalene concentrations were 3.6 times what’s allowed by the state’s long-term standard.

“In other words,” Rich said, “it’s a toxic soup out there.”

Even worse, she said, “No one can tell you what happens when you add these compounds together. It might be that in some cases they cancel each other out. Or they might be exponentially worse when you have a mix like that. And with what we know about chemicals, it’s probably exponentially worse.”

Subra told the Weekly that short- and long-term exposure to the chemicals have different effects. “The short-term exposure, the acute exposure to these chemicals, produces burning in your eyes, nose, throat,” she said. “But then there are the long-term effects, like cancer-causing agents and neurological problems that are likely to surface down the line.”

That’s not the kind of analysis that makes DISH residents breathe easily. Especially not Mike and Megan Collins, who lived next to Lloyd Burgess’ ranch for four years.

The Collinses lived on Chisum Road from mid-2005 until May of this year. Theirs was one of several upscale brick homes built on land Burgess had sold for development, next to the 30-acre farm he still owns.

“We never would have moved there if we’d known they were going to put all those compressors against our back fence,” Mike Collins said recently. “I mean, when we moved there it was very pretty, with trees lining the fence, just beautiful.” When the compressor stations were built, he said, “we tried to ignore them, but we always heard them, whether it was the relief valves going off or the gas pumping.”

In January, Megan began to have fainting spells. “She had two of those, and then she began to have problems with her balance. So her doctor sent her to a neurologist in Houston who ran a battery of tests,” her husband said. The tests found nothing wrong, but her symptoms persisted. In May, the couple moved to Fort Worth.

Just after the move, “my wife had a mini-stroke – something they told us was uncommon for a healthy 32-year-old female,” Mike Collins said. “And the doctors can’t figure out what is causing it.”

Megan was even tested for genetic problems, and still the doctors found nothing. But in the past few weeks, after learning of the results of the August air study in DISH, her doctors have begun to look into possible connections between the chemicals Megan was exposed to and her neurological problems.

“The doctors don’t know yet if there is any connection,” Mike Collins said. “And we’re hoping there’s not any, but you have to wonder. And even if there is, how are we going to fight those gas companies?”

Subra said that, if Megan Collins were exposed, over several years, to the kinds of chemical found in the Wolf Eagle study, it could be more than enough to cause neurological problems. “Two years is sufficient time to cause neurological damage,” she said.

Subra said that, if Megan Collins were exposed, over several years, to the kinds of chemical found in the Wolf Eagle study, it could be more than enough to cause neurological problems. “Two years is sufficient time to cause neurological damage,” she said.

Unfortunately, if it turns out that Megan Collins’ problems were caused by the chemicals she routinely inhaled, moving away won’t necessarily restore her to health.

“You will not be automatically safe from the chronic, long-term health conditions just because you remove yourself from exposure to those chemicals,” Subra said. “The damage could have already been done or could still show itself down the line, years later.”

She said that emission controls and vapor recovery systems on the compressors are two easy steps needed to reduce the chemicals in the air at DISH. “We’re hoping that the information in this study will lead to a state or federal agency stepping in and ordering those steps to be taken to reduce the level of those toxic chemicals in the air,” she said. “That’s been accomplished in Mossville, a community in Louisiana, and in Baton Rouge, and along Cancer Alley – the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans,” Subra said.

It’s not likely that the gas companies will accept the Wolf Eagle findings without a fight.

In May and June, Wolf Eagle conducted similar ambient air studies at the Westworth Village farm of Deborah Rogers, who has a gas well site just over her back fence. The study there showed the presence of several dangerous chemicals at levels that exceeded both short- and long-term levels allowed by the state.

In response to the findings, Chesapeake officials told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that several other sources likely were responsible for the toxins. The city of Fort Worth then commissioned a review of the study by Industrial Hygiene and Safety Technology Inc. That company’s experts concluded that the Wolf study was “rudimentary in scope and design” and called the results “inconclusive at best.” Identification of some of the chemicals was “tentative,” Industrial Hygiene officials said, and reports of the chemicals’ concentrations “are necessarily estimates.”

“There were two things about that review that struck me,” said Rich. “They talked about tentatively identified compounds, and it’s true there were several of those, but at the same time there were several very clearly identified toxic chemicals that are generally identified with gas wells and production.

“The review also suggested that Lockheed or the Carswell Naval Air Station and Joint Reserve Base might be the source of the chemical thumbprints we found. But the chemicals we found are not typical of what one would find at an airport,” she said. They are typical near gas drilling operations, however. “And knowing that, we can make a reasonable assumption by tracking back the chemical to the nearest probable source,” she said.

Fort Worth has not weighed in on the DISH study, but officials of the Texas Pipeline Association, according to news reports, have questioned the study’s methodology. Celina Romero, spokesperson for the association, was out of the country this week. Officials of the group said they questioned the study’s methodology but that only Romero could comment on their behalf.

Rich said her researchers don’t go in looking for a specific chemical or a specific outcome. “We do an array of analyses, and as a scientist, I can say that we’re only looking to find what might be there,” she said. “Our job is just to report on what we found and the most likely source [of it]. In the Rogers’ case, it was the gas well; in the DISH case, it was the compressors.”

Tillman said that each of the companies that has a gas compressor at DISH has told him that their emissions are within acceptable levels established by the federal Environmental Protection Agency. “And that might be so,” said Tillman. “But what happens when you have 11 of these things sitting next to each other? Even if each one individually is acceptable, add them up, and you wind up with nearly 11 times the acceptable level of toxins being released into our air.”

How so many compressors were allowed to be built so close together is an unanswered question. Each compressor is required to obtain a permit from the state for their emissions – actually an enforcement of EPA standards, delegated to TCEQ. To obtain the permit, a company must identify the chemicals it expects to release into the air; the permit sets limits on the amounts of those chemicals that can legally be released each year.

“What was done at DISH is unconscionable,” said a gas company insider who asked that his name not be used. “Atmos Energy bought a strip of land just outside of DISH and put a compressor on it. Fine. But then Atmos subdivided that land into several pieces and sold them to the other energy companies that also built compressors. Now that whole piece of land should have been looked at as a single pad, with all of the compressors having to share a single permit, yet somehow TCEQ permitted them all separately. That just can’t happen.”

The same thing happened at the smaller in-town site with the four compressors, he said.

“They can’t do it, but they did,” Tillman said. “And at the smaller site they didn’t even bother to build walls between them to pretend they weren’t a contiguous single pad.”

The air-quality study – and the DISHers’ screams of outrage – may finally be having an effect, however. TCEQ spokesman Terry Clawson wrote Tuesday in an e-mail that his agency has now scheduled investigative visits to the DISH sites to determine if the compressor stations have proper permits and are complying with emission limits.

TCEQ’s belated move toward regulation probably also has a lot to do with the EPA, which in the last few weeks has served notice that Texas’ lax enforcement of environmental laws will no longer be tolerated. An EPA official said Tuesday that the agency is aware of DISH’s situation but hasn’t determined what to do about it.

DISH officials and residents aren’t opposed to all gas drilling or the kinds of industrial activities that come with it. But many of them are furious at how it’s been handled in their town and at the state’s part in what has happened.

DISH officials and residents aren’t opposed to all gas drilling or the kinds of industrial activities that come with it. But many of them are furious at how it’s been handled in their town and at the state’s part in what has happened.

“I am against the way these people have elected to operate – quick and dirty methods, cheap methods,” Cisco, the town commissioner said. “It’s regrettable that the Railroad Commission and TCEQ have hoodwinked us into thinking they are protecting the citizens of our community when it seems more like they’re on the payroll of these companies.”

Tillman agreed. “How on earth could the people of this town suffer and complain about the air quality for so long, and I am the first one to do an air quality study?” he said. “This is squarely on the shoulders of TCEQ, and they let this happen to us. I just feel betrayed by the state.”

Tillman said some of the gas companies briefly talked about buying up all the property near the two compressor sites. “But when they saw how many people there are and what the land values should be, well, that was the end of it,” he said.

He also said that, when the drilling companies go to other towns and tout their industry and offer their bonuses and royalties, they are sometimes asked whether other towns will end up like DISH. He said they always promise that nothing like DISH will ever happen to other towns.

The mayor said some residents are considering suing the gas companies over the considerable loss in value of their homes and other properties. But Chuck Paul is thinking a bit more radically.

“I’d like to form a pipeline company and start condemning land under the Texas legislators’ families’ property,” he said. “Let’s see how they feel when they know what we’re going through.”

Failing that, he said, he may one day just give what’s left of his property back to the bank. “It’s frustrating to know that I’ve got to work to pay the mortgage on a place that isn’t worth the mortgage anymore,” he said.

One North Texas banker told the Weekly that the use of eminent domain and the rampant placement of industrial facilities like compressor stations and pipelines in residential areas is beginning to worry people in his own industry – for exactly the reason outlined by Paul. “We worry that the owner may not find his property has the value anymore to make it worth his or her while to pay the mortgage,” said the banker, who asked that his name not be used. “And if the value sinks low enough, we might just call in the note as a premptive solution.” Banks also might refuse to make new loans in similar areas, he said.

At the very least, Tillman said, he’s going to get a copy of the air-quality study into the hands of “all the people who have a stake in the compressor stations as well as state officials and the Railroad Commission. That way if those companies are ever asked in court whether they have ever been made aware of environmental problems related to compressor stations, they’ll have to say yes. And that might keep this from happening somewhere else.”

[…] lost about 30 of his 64 acre horse farm because of required easements by the natural gas industry, told the Fort Worth Weekly, “The gas companies pay a one-time fee for your land, but you lose the […]

You are so interesting! I don’t believe I’ve read

a single thing like that before. So wonderful to find someone with unique thoughts on this subject.

Seriously.. many thanks for starting this up.

This web site is one thing that is required on the web, someone

with a little originality!

[…] lost about 30 of his 64 acre horse farm because of required easements by the natural gas industry, told the Fort Worth Weekly, “The gas companies pay a one-time fee for your land, but you lose the right to utilize it as […]

[…] lost about 30 of his 64 acre horse farm because of required easements by the natural gas industry, told the Fort Worth Weekly, “The gas companies pay a one-time fee for your land, but you lose the […]

[…] lost about 30 of his 64 acre horse farm because of required easements by the natural gas industry, told the Fort Worth Weekly, “The gas companies pay a one-time fee for your land, but you lose the […]

This article presents clear idea in favor of the new people of blogging,

that genuinely how to do running a blog.

[…] lost about 30 of his 64 acre horse farm because of required easements by the natural gas industry, told the Fort Worth Weekly, “The gas companies pay a one-time fee for your land, but you lose the […]