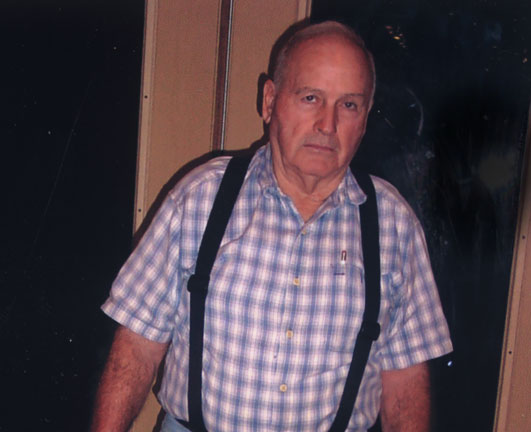

A mirror may be the best place for Willie Regan to find someone to blame for his current predicament. He says XTO Energy took control of his property in Mosier Valley through deceit – but he also admits that trusting an oil-and-gas landman rather than hiring an attorney was his biggest mistake.

The 73-year-old built roads and airplanes before he settled in Arlington in his 30s and started a pool-building business. Over the years, he made major deals on a handshake, contracts be damned. Six years ago, he retired to a farm near Yazoo City, Miss. and began building his dream home. He didn’t think he needed a lawyer for the XTO deal back in Texas.

“Why do you have to have an attorney every time you take a fart?” Regan said.

He’s learned the answer the hard way: XTO ended up with use of most of his Fort Worth land for next to nothing. “I’m not trusting a damn soul no more,” Regan said.

He’s learned the answer the hard way: XTO ended up with use of most of his Fort Worth land for next to nothing. “I’m not trusting a damn soul no more,” Regan said.

A few years ago, Regan’s six-acre tract on Mosier Valley Road in east Fort Worth was a habitat for dove, quail, and pecan trees. Today, most of the land is off limits to him, covered by a 4-foot-thick gravel gas-well site surrounded by a 6-foot security fence. Trees and birds have been replaced by noisy trucks coming and going at all hours.

Three years ago, Regan signed a gas lease with XTO Energy that gave him a bonus of $15,000 and royalties of 22.5 percent – an agreement he figured could earn him up to $500,000 over the course of the lease. The lease allowed XTO no surface use of the land.

However, a few months later, the landman came back asking him for surface use because, he said, XTO had not been able to work out surface-use arrangements with a neighboring landowner. The company needed a place to drill or there’d be no royalties and bonuses coming in. The landman representing XTO drew up an addendum to the lease, and Regan signed it, without consulting anyone or reading the fine print.

When, shortly after that, XTO began putting in a well on the neighbor’s property after all, Regan figured the surface use of his land was no longer needed by XTO and that the agreement was void. Royalties started coming in, though they quickly dwindled from $2,500 a month to about $300, as gas prices dropped.

Last year, Regan learned how wrong he was: XTO came to his property to drill after all. When he tried to stop them, they took him to court to force access. Then they put in a well and fenced off four of the six acres. The insult to injury came, however, when he learned that the addendum he’d signed, besides turning over surface use to XTO, also canceled his right to any royalties from the well that was sitting on his own property.

“You’d have to be in an insane asylum to sign something like that,” Regan says now.

Meanwhile, the gas drillers have left his entrance gate open many times, he said, allowing thieves to break into a locked tool shed and steal about $10,000 in construction equipment that he had allowed his son to store there. His plans to make money from the land as a sand pit are gone. And he’s turned over control of property for which he paid about $120,000 in exchange for about $35,000.

When he went to court to fight XTO, he said, the gas company threatened to take his land, his house, and everything else he owned if he didn’t live up to the contract and addendum he had signed. “XTO shafted us really big time,” he said.

Tom Covington, XTO’s vice president of investor relations, said it’s not XTO’s fault that Regan didn’t get a lawyer. “It’s hard to see how we tricked them into anything,” he said.

But Regan’s neighbor claims he, too, endured one broken promise after another from XTO.

Allen Tucker runs an earth-hauling business about a half-mile from Regan’s property. Tucker’s 12 acres, divided into several parcels, are included in the same 80-acre drilling “pool” that Regan’s land is in. Tucker also trusted XTO and neglected to get an attorney. He said he was fine with signing away his surface rights in exchange for cash bonuses for each gas well drilled on his land. He didn’t expect royalties. However, he said XTO told him they wouldn’t use much space and the land would revert back to him once drilling was completed.

On one of Tucker’s three-acre parcels, however, XTO’s pad site takes up all but a tiny slice of land. Tucker figured XTO would drill its well in a few weeks and then move off the property, and he’d be able to store sand and gravel on the land again. But he said the contract he signed allowed XTO to drill there for decades. Tucker might never be able to use the land again.

As someone who helps property owners and neighborhood groups negotiate gas leases, University of North Texas real estate professor John Baen has seen hundreds of such contracts.

“A man who represents himself is a fool,” he said after reading Regan’s lease documents. He said Regan’s $15,000 bonus is among the lowest he’s has seen for contracts signed in 2006.

“He [Regan] gave his land away,” Baen said. “He needed serious help, both economically and legally before he signed this thing. They didn’t hold a gun to his head, and he didn’t understand, but ignorance is no excuse.”

“He [Regan] gave his land away,” Baen said. “He needed serious help, both economically and legally before he signed this thing. They didn’t hold a gun to his head, and he didn’t understand, but ignorance is no excuse.”

Even though Regan said the landman who represented XTO promised him royalties as well as the $15,000, what’s written is what stands in court, Baen said. The landman in question works for Texhoma Energy, which does contract work for XTO.

Regan said that when the landman approached him about leasing his surface rights, he told Regan he’d get a $15,000 bonus for the first well drilled on his property and $10,000 for each subsequent well. Regan assumed he would still get the 22.5 percent in royalties specified in his previous contract. He drove in from Mississippi to sign the addendum.

When it all fell apart last year and XTO took him to court, Regan claimed that he had been “fraudulently induced” to sign the lease addendum. Regan said the landman had told him he wouldn’t get any royalties from the 80-acre pool if he didn’t sign over his surface rights.

In a deposition, the landman said he didn’t know about XTO’s decision to drill on the neighbor’s property until after Regan had signed the addendum.

“Do you feel any obligation to explain the terms of those documents to them?” XTO lawyer Jeffrey King asked the landman.

“No, sir, I do not,” he answered.

In the courthouse hallway prior to a scheduled court appearance in late December, lawyers for Regan and XTO huddled to discuss the situation. Then King told Regan that XTO was offering to bump the $15,000 bonus payment up to $25,000 and would also pay Regan’s $10,000 attorney’s fee – but nothing else. King said Regan would get no royalties, and if he didn’t agree to XTO’s offer, the gas company’s attorneys were prepared for a lengthy court battle.

A defeated Willie Regan agreed to the deal.

Covington, the XTO vice president, said Regan’s financial situation “is

not something we should concern ourselves with.”

So the land that Regan had hoped would provide retirement income for him currently provides income only as a rented horse pasture on part of the land not used by XTO. And Regan himself is back in Mississippi, bitter about how he was treated by XTO.

His son, Bill Regan, still stores equipment for his business in a shed on the land. But he can’t hunt there the way he used to or enjoy shade from the big pecan trees that are gone now. He said he gets depressed whenever he sees the pad site that covers the bulk of the land.

“I’m not going to inherit anything,” he said. “The land is just junk now.”