A little more than a year ago, the Barnett Shale gravy train was shooting through North Texas at blinding speeds. Even while some residents were accusing the city council of surrendering Fort Worth’s future and environment to the gas drillers, thousands of property owners were getting on board with companies like Chesapeake and XTO as fast as they could, eager to get their fair share of the loot.

Natural gas prices were at record-high levels, and property owners who had waited out the negotiating process were reaping big rewards. Neighborhood groups banded together to negotiate better deals with the powerful companies than individual property owners could have gotten. Waiting for the bonuses and royalty rates to go higher seemed like a good strategy.

Natural gas prices were at record-high levels, and property owners who had waited out the negotiating process were reaping big rewards. Neighborhood groups banded together to negotiate better deals with the powerful companies than individual property owners could have gotten. Waiting for the bonuses and royalty rates to go higher seemed like a good strategy.

In April 2008, the Southeast Arlington Communities of Texas (SEACTX) negotiated a deal with XTO Energy that would bring in bonus money of $26,517 per acre and a royalty rate of 26.5 percent – among the highest in the Barnett Shale play. When leaders of SEACTX, representing about 7,000 property owners with about 5,000 acres, did the math, they figured that more than $100 million in upfront bonuses would be coming into their community of mostly modest to middle-class neighborhoods.

Four months later, the Southwest Fort Worth Alliance (SFWA) made a similar deal with Vantage Energy. The bonus was set at $27,000 an acre and the royalty rate at 23 percent. SWFA figured that more than $200 million in bonus money would soon be in the hands of the 25,000 property owners the consortium represents.

Well, that was then and this is now, when natural gas prices have fallen to less than half what they were in early 2008. And as anyone who has been following the Barnett Shale saga knows, drilling companies pulled out of those deals and others in mid-October of last year. Some property owners, whose bonus checks were processed prior to the cancellation, got paid. Tolli Thomas, a spokeswoman for SWFA, estimated that 4,000 to 5,000 people in her area got the money promised to them – and the other 20,000 or so did not.

The gas drillers blamed market forces for the cancellations. Gas prices had fallen significantly throughout the summer, and the big deals didn’t make economic sense anymore, they said. Gas company officials also contend that the deals they’d made with neighborhood alliances weren’t binding after all – that only contracts with individual property owners, who had filled out the proper paperwork, were enforceable. In fact, in at least two cases, companies are alleging that even those contracts were not enforceable until property owners got their checks.

So what does make a binding contract with a gas company? Can the drillers really ignore the promises they made, verbally and on paper, to neighborhood groups and, in some cases, to property owners? Are market fluctuations really a valid legal reason for backing away from signed contracts? Or were market fluctuations truly the reason for the widespread abandonment of those contracts? Thomas and others are now questioning that.

“The market fluctuations didn’t match up with the timing of when the deals were pulled,” she said. “It is still somewhat of a question in all of our minds how the market alone had caused this. We really question what was going on behind the scenes. These are questions that need to be answered by the companies.”

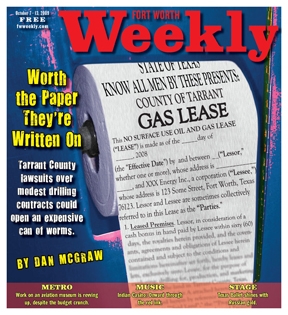

In the coming months, those questions and others will be asked officially in Texas courts – maybe in Dallas, maybe in Tarrant County. A consortium of three Dallas law firms has filed the first two of what likely will be many lawsuits over the neighborhood associations’ deals that were negotiated but never fulfilled and individual property owners’ contracts that were signed but on which the companies have refused to pay off. The issues go beyond what’s owed to a few individuals: Plaintiffs in the initial suits are claiming that the gas companies acted in collusion to pull out from under these record-setting bonus and royalty rate deals, thus allegedly violating deceptive trade practice and antitrust laws.

Kip Petroff, lead lawyer for North Texas Lease Litigation, the consortium formed by the three law firms, said the lawsuits his group have filed allege that “this is real estate fraud, and the gas companies deceived these homeowners who had negotiated in good faith.”

Gas companies involved wouldn’t respond to Fort Worth Weekly‘s request for information and interviews. They have said in court documents that Petroff’s allegations have no merit.

This isn’t Petroff’s first major-litigation rodeo. He was the first attorney nationwide to get a judgment against a big pharmaceutical company in the “fen-phen” diet pill scandal. Following that first $23 million victory, he worked with law firms across the country on thousands of fen-phen cases.

In the gas contract dispute, Petroff said, “There was more than $300 million due the homeowners of these two neighborhood groups, and the facts are screaming out that something really wrong happened here. We are going to get the answers to these questions.”

Getting the answers won’t be easy. Some experts in real estate and antitrust law say that proving antitrust violations and enforcing agreements with neighborhood groups will be uphill battles.

But Petroff is thinking big. Rather than just suing the companies that the two neighborhood groups signed up with, he is asking that 21 drilling companies operating in this area be required to turn over records showing how they did business in the first eight months of 2008. And even though the first two cases are worth less than $5,000 each, those lawsuits could open the barn door to tens of thousands of other cases during the coming year. (A two-year statute of limitations means that any suits pertaining to gas company actions in 2008 must be filed by October 2010.)

Those who found out the hard way that their gas leases or neighborhood group agreements might not be enforceable are watching the proceedings closely.

“From the comments I’ve heard from a lot of my neighbors in southwest Fort Worth, there is a lot of interest in seeing what the legal options are,” Thomas said. “The offers we are getting now are $2,500 an acre at most, less than 10 percent of the offer we had with Vantage Energy. … A lot of people think that going to court may be their only next logical step.”

Petroff’s first two cases are on behalf of Arlington property owners who actually received bonus checks from XTO but never got to cash them.

Even though the plaintiffs live in Tarrant County and XTO is based here, Petroff and the consortium filed their suits in Dallas. His theory? That because some of the companies in the list of drillers and landmen firms he’s suing are based in Dallas, either county would have jurisdiction.

And that may be the first major battle in this legal war. Petroff’s critics say he’s forum-shopping, avoiding Tarrant County, where the gas companies have a powerful public presence and many political supporters. Defendants, indeed, are seeking to move the cases here.

Willie and Carmen Booth, who live in the Meadow Vista Estates neighborhood in Southeast Arlington, were the first plaintiffs to file suit. Petroff wouldn’t let them talk to the Weekly for this story. But according to documents filed in the lawsuit, they signed their agreement with XTO in August 2008, after negotiations between SEACTX and XTO were completed. Since they own a little less than a fifth of an acre, their bonus was supposed to be $4,932. But the check they received from XTO was for $4,269.

An agent of Permian Land Company, who represented XTO in signing up property owners in the area, was the Booths’ contact. According to the lawsuit, he agreed that the check had been miscalculated and said the Booth’s were due an additional $662.93. But rather than just cut an additional check for the difference, the agent asked the Booths to return the original bonus check and said they would receive a new, correct check “shortly thereafter.”

An agent of Permian Land Company, who represented XTO in signing up property owners in the area, was the Booths’ contact. According to the lawsuit, he agreed that the check had been miscalculated and said the Booth’s were due an additional $662.93. But rather than just cut an additional check for the difference, the agent asked the Booths to return the original bonus check and said they would receive a new, correct check “shortly thereafter.”

The Booths contacted Permian again in September asking about their check. On Oct. 13, 2008, the couple received a letter from Permian – but the enclosed check was only for $662.93. “Shortly after receiving the original supplemental check, [the Booths] were advised by Permian and XTO not to cash the supplemental check and that their lease … was being terminated,” the lawsuit alleges.

Velma Myles also received a flawed check, for a different reason. At the time that Myles sent in her paperwork to XTO, she was going through a divorce and mistakenly filled in her husband’s name along with her own on the lease deal, although the property had been held solely in her name.

Petroff also declined to allow Myles to be interviewed for this story. But according to the lawsuit, when she went to a signing party in July 2008 to pick up her check, she realized it had been erroneously made out in both her and her husband’s names. She informed XTO’s agent that she was the sole owner of the property. The agent said he would contact her when a corrected check arrived and she could pick it up and sign the lease at the same time – standard procedure on lease agreements.

According to the lawsuit, Myles contacted XTO and its leasing agents three times during the late summer and early fall and was told the check was on the way. But the new check was never produced, and by the second week of October, XTO had backed out of the deal.

The gas companies maintain that the lease deals are not legally binding until the property owners cash the bonus checks. In the cases of the Booths and Ms. Myles, neither cashed a check as part of their lease agreement.

“The … problem here is, who is responsible?” said University of North Texas real estate professor John Baen, who has consulted with some property owners on Barnett Shale leases. “When you have a real estate deal gone bad, who is at fault? The seller, the buyer, the agent, the loan officer? There are a lot of people involved in these lease deals, and it is hard – and that is how the system is set up – to find one group at fault in court.”

The second big battle is likely to be over the antitrust issue. As part of the discovery process, Petroff has sent a list of 255 requests for information to each of the 21 companies being used, including broad-ranging questions about their business operations. He says the information is key to proving his antitrust allegations.

The gas companies have responded by calling the requests an “improper fishing expedition under Texas law.” Judges Eric Moye and Jim Jordan, in whose Dallas district courts the two initial lawsuits were filed, have yet to rule on that question. If either rules against Petroff’s group, the antitrust allegations could be cut from that case, along with most of the defendants.

Both the Booth and Myles cases claim that XTO and the other companies engaged in a civil (not criminal) conspiracy by “conceiv[ing] a plan or scheme in concert with each other [to] drive the bonus and royalty payments to a far lower amount than was being paid at the time.”

The object of the scheme, the suits allege, was to circumvent the “natural market forces” that had been sending royalty and bonus rates higher and instead to substitute artificially low bonus and royalty prices, thereby increasing the companies’ profits and injuring landowners’ interests.

Recent court rulings have made it tougher for plaintiffs to get antitrust allegations to trial. Two years ago, the U. S. Supreme Court ruled that merely proving competitors in an industry had policies in lockstep and offered consumers very similar rates for their products isn’t enough.

“It’s very hard to prove now,” said University of Texas-Austin law professor Lino Graglia, who specializes in antitrust issues. “You have to prove a conspiracy, and the only way to do that is to have physical evidence that agreements were made by the competitors and there was damage felt by interested parties.

“If the plaintiffs don’t come up with specific facts, facts that show there was contact between the defendants and actions taken, then the judge will likely throw out the antitrust claim,” he said.

Gas company attorneys did not return calls from the Weekly seeking comment. But in news reports last October, analysts suggested the moves were necessary because of rapidly falling gas prices. In July 2008, gas prices on the open market were about $13 per million British Thermal Units (the industry measuring standard) but had fallen to $6 per BTU by October. The decline continued in 2009, to a low of less than $3 last month.

Analysts believe the market has bottomed out for now. Last week, the price was up to just under $5, and some analysts expect the price to rise substantially this winter, perhaps to $7.50.

Petroff pointed out that industry experts have always said that Barnett Shale wells are profitable only in the $6 to $7 per BTU price range. Then there is the aspect of long-term investment. “These [gas] companies have always told the people they were leasing from that the Barnett Shale would be lasting many decades,” he said. “So you shouldn’t be trying to change the market just because the price has gone down for a short time. That is deceptive trade practice, and we will prove that.”

One prominent Dallas antitrust lawyer who asked not to be named – and whose firm is considering doing legal work for some of the gas company defendants – said the North Texas Lease Litigation suits shouldn’t get far.

“You can’t get a verdict just by simply showing that the companies all took the same course of action,” the attorney said. “You have to show documented price-fixing. You have to show that the competitors agreed not to compete. Thus far, [the plaintiffs] haven’t shown any of these facts at all.”

“You can’t get a verdict just by simply showing that the companies all took the same course of action,” the attorney said. “You have to show documented price-fixing. You have to show that the competitors agreed not to compete. Thus far, [the plaintiffs] haven’t shown any of these facts at all.”

Petroff said he’s not worried about the antitrust component of the case being thrown out. “If they don’t want to call it antitrust, we have also filed claims that allege real estate fraud, misrepresentation, or deceptive trade practices,” he said. “Those involve some standards that might be a little different, but they still involve these companies having agreements with one another to get the lease deal agreements lower.”

Linda Razzano helped negotiate the SEACTX lease agreement with XTO. She is an executive director of a nonprofit that helps neighborhood groups manage their affairs, and she’s seen the tactics that gas companies use in dealing with neighborhood groups.

“What we started seeing a few months after we signed that deal in April [2008] was that the process was slowing down,” Razzano said. “Paperwork was being lost, and checks were not issued correctly. There just seemed to be delay after delay. And I don’t think it is too much of a stretch to think these delays were part of a plan to hold back the process and sign fewer property owners to leases.”

There is also a big question about whether the agreements that neighborhood associations signed with the gas drillers are binding or whether contracts with individual property owners superseded them. One factor working against the plaintiffs is that the lease agreements sent out to individual property owners make no mention of the bonus amounts per acre, only the royalty percentage. However other paperwork sent out to property owners does make mention of the bonus amount negotiated and how much their property is worth.

“There is no single document signed by both the neighborhood associations and the gas companies,” said Dallas attorney Chris Payne, a member of the legal team working with Petroff and who advised both SEACTX and SFWA during their negotiations.

Part of the reason there was no single document in the deals, Payne said, is that gas companies and landmen were used to working in rural areas, dealing with individual big-property owners. In urban drilling, the companies were dealing with large groups of owners, and no one had much experience in processing the paperwork for so many properties. The gas companies contend that the deals with neighborhood associations were not binding at all, merely a starting point for dealing with individual property owners.

But Payne believes there is a binding contract in place. When the gas companies sent out postcards to property owners advising them to get the needed paperwork in, the postcards contained the per-acre bonus rates that had been negotiated. Press releases from both Vantage and XTO and from the two neighborhood associations announced the deals publicly.

“Just because there was not a single document that was signed by both parties does not say that there was not a legal agreement,” Payne said. “The lease terms, royalty rates, and bonuses per acre all appear in multiple documents. We say that everyone who was represented by these neighborhood associations did have a binding contract with the gas companies, and that contract was reneged upon.”

Others disagree. “My opinion is that the neighborhood associations will have a hard time saying these are binding contracts, because they didn’t represent all the property owners,” said UNT’s John Baen, “The deals with the neighborhoods are contract offers, but they are not fully consummated until the individual property owner signs and the check is cashed.”

Many issues in these two cases will be resolved in the next month or so. The Dallas courts will likely rule on the defendants’ motions to move the cases to Tarrant County, on how much company information needs to be given to the plaintiffs’ attorneys, and whether the plaintiffs have produced enough evidence to warrant bringing the antitrust accusations to trial.

The plaintiffs’ requests for long lists of documents from the gas companies are being fought hard by the defendants. Lawyers for Carrizo Oil & Gas, for instance, claim that answering the requests would reveal trade secrets and unduly burden the company.

The Carrizo lawyers contend they shouldn’t have to answer so many questions on a case worth less than $5,000, in which they claim no involvement. The company is being asked to provide all written documents and e-mails dealing with its business practices, any dealings with co-defendants, all lease deals made since January 2008, and all contacts with landmen during the same period.

“Plaintiffs, instead of aiming their discovery at discrete, pending issues, have applied a scorched earth approach, leveling sweeping, exploratory discovery requests at Defendant Carrizo,” wrote attorney Michael Kennington of Houston.

Baen said the requests for documents “sound like a lot of gobbledygook by lawyers looking to force a big payday. This looks like it will turn into something like a class-action lawsuit, where the property owners get very little and the attorneys get a lot.”

Petroff said his questions are detailed because the judge asked him to be specific. “I want to know their acquisition strategies, and I want to know everything related to their lease practices and what they told the landmen and property owners,” he said. The gas companies would fight the requests no matter how they were worded, he said.

Petroff said his questions are detailed because the judge asked him to be specific. “I want to know their acquisition strategies, and I want to know everything related to their lease practices and what they told the landmen and property owners,” he said. The gas companies would fight the requests no matter how they were worded, he said.

His requests aren’t excessive, Petroff said – but if he gets all the information he’s asked for, he acknowledged, his legal consortium might have to rent warehouse space to store the resulting stacks of documents.

So how did three firms of Dallas lawyers get involved with gas drilling cases from Tarrant County? It started with Dallas attorney Chris Payne, an old friend of Petroff, who helped SEACTX and SWFA craft their deals. When the deals were pulled last October, Payne met with Petroff to see if there was a legal strategy that could help the neighborhood associations.

“When these deals fell through, we could see that something wasn’t right,” Petroff said. “I think Chris wanted my input because of my experience with mass torts” – which is considerable.

In the late 1990s, about six million people, mostly women, were taking a diet drug dubbed “fen-phen,” the shorthand name for the blending of fenfluramine and phentermine. In 1997, some of those taking the drug began to complain about heart valve damage and pulmonary hypertension – both potentially fatal health problems.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration asked the pharmaceutical company Wyeth to take the drug off the market. A lot of lawsuits were immediately filed, but in order to be successful, the plaintiffs’ lawyers had to find out how much Wyeth officials knew about the risks associated with the drug and when they knew it.

Petroff won the first fen-phen case in the country in 1999, on behalf of a Canton, Texas, woman, for a verdict of $23 million. He won because he was the first lawyer to force Wyeth to turn over nearly five million pages of documents, some of which indicated the company’s medical workers had worries about the drug’s safety.

Petroff said he has participated in 100,000 fen-phen cases during the last decade, working with more than 100 law firms. He estimates those cases have brought in about $500 million in verdicts against Wyeth.

Petroff is also president and executive director of the New Hope Foundation in Dallas, a nonprofit he helped found two years ago that helps the underprivileged with home repairs and other needs. “I was very lucky and fortunate with the fen-phen cases, and I just figured it was time for me to give back,” he said.

Clearly, Petroff believes that the two current Tarrant County lease cases may lead to many more lawsuits. “There are at least 30,000 people out there who have legitimate gas well lease claims just in Tarrant County,” Petroff said. “But before we start full-blown discovery on so many cases, we have to have some idea of where we are at. That’s what we are doing now.”

He acknowledges the complexity of the lawsuits but thinks there will be more than enough evidence to go forward with them. “We aren’t going to base this upon great legal machinations, just the facts,” he said. “Sure, we will be making big legal fees if we win a lot of these cases. But people are missing the point: Thousands of people had a legal contract and were relying upon that to help them get a little money to save or pay off some bills. But they were denied that, and we have a legal obligation to rectify that.”

And what has happened since the deals were pulled? In the SEACTX neighborhoods, Razzano said, “The land- men are all back knocking on doors. But their offers are often in the $300 an acre range. And we did this deal so we wouldn’t have all these gas people bugging us. It is very disappointing.

“The media and the gas companies always acted like this money was like manna from heaven, Christmas money,” she said. “But for most people it was a few thousand dollars after taxes, and they had plans to pay off some bills with that money. We waited our turn, worked in compliance with the gas drillers, and spent so much volunteer time working out a fair deal for both sides.

“I feel for everyone in this neighborhood,” she said, “because the gas companies have hurt our neighbors repeatedly, and now they are rubbing our faces in it.”