For those outside the ‘hood, the perception of late night youth programs at city community centers is that of older teenagers shooting hoops — you know, would-be gangbangers who are staying off the streets and away from criminal mischief. The cynics, of course, figure some of the teens are just using the gym as a place to get together to plan their crimes for later.

But last Friday night at the Como Community Center on Fort Worth’s West Side, it was clear that the city-sponsored late night program is about much more. Sure, there were boys and girls playing basketball. But there were also a couple dozen 12-year-old boys — members of the Como Lions football team — getting fitted for helmets. In another room, a half-dozen women were getting their exercise in a belly-dancing class. Elsewhere in the building, job seekers were using computers to write resumés and get employment advice from volunteers. Volunteers at the center also counsel youths with problems and tutor those who need help in school.

But last Friday night at the Como Community Center on Fort Worth’s West Side, it was clear that the city-sponsored late night program is about much more. Sure, there were boys and girls playing basketball. But there were also a couple dozen 12-year-old boys — members of the Como Lions football team — getting fitted for helmets. In another room, a half-dozen women were getting their exercise in a belly-dancing class. Elsewhere in the building, job seekers were using computers to write resumés and get employment advice from volunteers. Volunteers at the center also counsel youths with problems and tutor those who need help in school.

But, just as important as the specific activities, the several hundred people inside the Como Community Center were taking pride in their community. Seniors and toddlers, parents and their kids, community leaders and difference-makers — all were there to make sure their neighborhood is moving in the right direction.

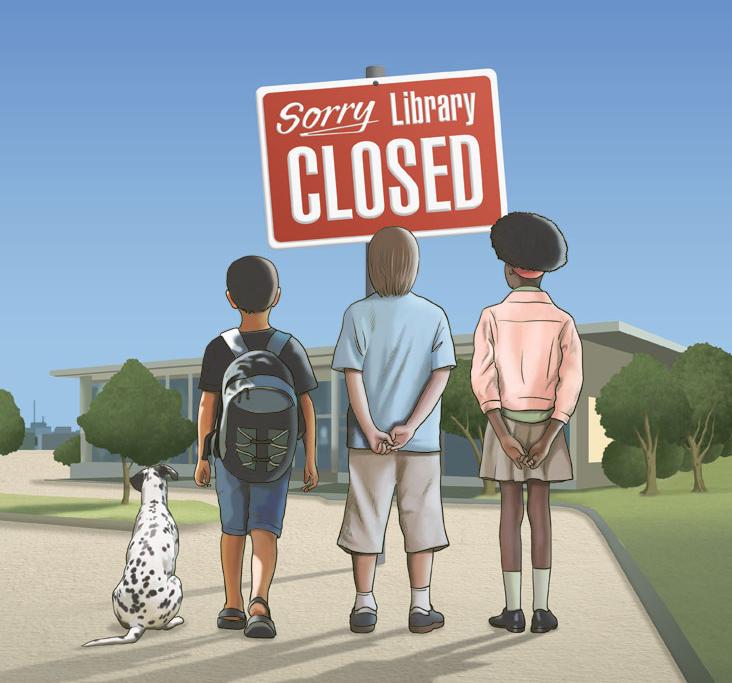

That progress might get derailed in the coming months, however, run off the track by the freight train of a city hall budget crisis. Under the cuts proposed, late night programs at Como and four other community centers might be eliminated. The centers would be closed at 6 p.m. — as opposed to midnight on the weekends for the late-night programs — and 10 staffers would lose their jobs. City staffers calculate the move will save more than $577,000: a respectable chunk of the $59 million in cuts needed to be found in the next two weeks to cover the city’s worst projected budget shortfall in nearly 20 years.

City administrators warned council last year around this time that the slashes made then were mere paper cuts compared to what was going to happen this year. And that was before the depth of the current recession was clear, before drops in natural gas prices started to affect local coffers.

But in other ways, some city staffers, neighborhood leaders, and council members say, this crisis has been building for years — due not to international financial conditions or the gas market but to actions taken at Fort Worth city hall.

And now, neighborhood leaders and others charge, the needed financial fixes are being piled far too heavily on the services and programs that most directly affect the city’s poor. Pools, libraries, after-school programs, the day labor center, graffiti abatement — all could be shrunk or eliminated.

It’s a trend that Dorothy DeBose, chairwoman of the Como Neighborhood Advisory Council, isn’t happy about. At a recent budget workshop, Mayor Mike Moncrief told the council, “Fort Worth is going to look a little different this year than it has before.”

DeBose showed obvious frustration at that statement. “Some neighborhoods are going to look different, but other neighborhoods are going to look about the same,” she said. “The neighborhoods that are going to look different are the poor ones, and the neighborhoods that will look the same are the ones that have money.”

The basic strategies proposed by city staffers to cut $59 million from a $1.2 billion budget have been well publicized: More than 200 city jobs will be cut or remain vacant, and those who are still employed will have to take eight unpaid furlough days. City Manager Dale Fisseler asked all city departments except fire and police to present suggested cuts totaling 10 percent of their budgets.

The expected cuts represent about 5 percent of the city’s total budget. But about $700 million of the city budget goes to retire bonds for capital improvement projects. The other $500 million is in the general fund, which pays salaries of city workers, police and fire protection, maintenance of city facilities and programs, and city services like community centers. All of the cuts will come from the general fund, and the shortfall of $59 million is about 12 percent of that.

The city council is due to approve the budget in about two weeks. If they accept staff proposals, street maintenance will be cut by about $763,600, mostly through layoffs. The Day Labor Center is scheduled to be closed, for a savings of more than $271,000. Shrinking the graffiti abatement program could save $134,450. Council members may be forced to choose whether to leave only one of seven city pools open or to close the last one to keep two branch libraries operating.

But even two years ago, there w as a feeling that Fort Worth was somewhat recession proof. The city was growing in jobs and population; retail development and office construction rates were outstripping other parts of the country and even other parts of North Texas.

as a feeling that Fort Worth was somewhat recession proof. The city was growing in jobs and population; retail development and office construction rates were outstripping other parts of the country and even other parts of North Texas.

Then there is the Barnett Shale natural gas money coming in, adding about $12 billion a year in North Texas economic activity. The city should get about $1 billion over three decades for its leases of public land to the gas drillers. Even with the downturn in gas prices this year, Fort Worth was still getting decent natural gas revenue streams that other cities were not. Gas well income includes higher sales taxes from natural gas company workers, ad valorem property taxes on the mineral rights, and a growing property tax base from the economic activity associated with the drilling.

So the question that many citizens are asking right now is how much of this big budget shortfall is simply the result of the nation’s economic problems and how much is self-inflicted. “I don’t think we can blame this all on the current economy,” said Tolli Thomas, the treasurer of the Wedgwood Square Neighborhood Association. “And you can’t just blame this on the decline of natural gas prices.

“I think in the past few years, the city staff and council weren’t paying attention to a lot of things that were going on,” Thomas continued. “We had all this growth, and a reasonable person could see it wouldn’t last forever. But they just kept spending and spending and giving out tax breaks. But just because you have some extra money, you don’t have to spend it all.”

Assistant City Manager Fernando Costa agrees with Thomas somewhat. “I think obviously a big part of [the budget shortfall] is attributable to the recession that is affecting governments around the country,” he said. “But we can attribute some of our current predicament to policy decisions we’ve made from time to time throughout the years.

“These were not bad policy decisions when taken individually, but taken collectively they been significant factor in our current problem,” Costa continued.

Those collective decisions involved inadequate infrastructure spending, too many tax exemptions for homeowners and businesses, and not preparing well enough for higher pension and healthcare costs for retirees and city employees.

Costa, the city’s former planning director, also points to “the significance of inefficient land use patterns.” Translation: Suburban sprawl is expensive, requiring the city to extend its network of services and infrastructure farther and farther. That bill has now been delivered. The city’s mistake, Costa said, was focusing on housing developments on the edges of the city and not enough on urban infill development, which, from the city’s standpoint, is much more efficient.

I n a presentation to the council’s first budget workshop last month, Costa explained “how we got here.” He harkened back to the early 1990s, when Fort Worth faced a similar budget crisis, mainly from the closure of Carswell Air Force Base, declines in defense spending, and falling revenues from a decline in property values. The nation was also experiencing a recession at that time.

n a presentation to the council’s first budget workshop last month, Costa explained “how we got here.” He harkened back to the early 1990s, when Fort Worth faced a similar budget crisis, mainly from the closure of Carswell Air Force Base, declines in defense spending, and falling revenues from a decline in property values. The nation was also experiencing a recession at that time.

The city responded by cutting the city’s workforce by 12 percent over a three-year period, reduced services, including reduced hours at libraries and community centers. Sound familiar?

But the city also increased its property tax rate by 7 cents per $100 of valuation over four years, peaking in 1994 at 97 cents. Since 1994, Fort Worth has dropped the property tax rate to just under 86 cents (still among the highest in the state). This time around, there is not even a hint that city council will consider any type of property tax rate increase to at least keep up with some service demands. Only councilman Sal Espino has raised the issue, and he only wanted to know what effect a one-penny increase might have on debt service for bonds that build roads.

While Fort Worth kept dropping the property tax rate, it also was giving out a lot of tax breaks. About 20 percent of city real estate is covered by homestead exemptions today, costing the city $28.5 million this year in forgone taxes. Add to that tax breaks for corporations and the tax-increment finance districts, and pretty soon you’re talking real money.

Suburban sprawl growth brings in more property taxes, but those seldom cover the entire costs of the new infrastructure projects needed for developments like roads and sewers. The city has also largely under-funded capital improvements projects and street improvements in recent years, Costa told city council, and that bill is coming due now.

Staffers estimate that inadequate storm sewers and street improvements alone are worth $2 billion. Costa estimates that 36 percent of the current city building facilities are in poor condition. The parks department spends a little more than $1 million a year on maintenance, but more than $5 million is actually needed.

These problems were exacerbated by the city’s failure to do financial audits in a timely manner during the past five years. An outdated software system was partly to blame, but city staff didn’t seem concerned that they didn’t know what the city’s revenues were being spent on and that millions of dollars were missing. Those problems have largely been rectified, and the city’s bond rating has now moved up to “strong.”

What about the city’s Barnett Shale money? Couldn’t that be used to close the gap? Since the drilling began about four years ago, the city has received about $93 million in revenue. Use of drilling profits from some wells is limited by federal government rules. For example, the lease and royalty money at the city’s three airports must by used by the airports.

But other restrictions have been brought about by city policy. From the beginning, Moncrief and the council decided to use about half the money for capital improvement projects and put the other half put into a general endowment fund — a savings account for a rainy day.

But the endowment fund policy is deceiving. About $15 million of that has been set aside for future street improvement projects. The city has also proposed using $6.7 million of the mineral lease property tax money to save the Directions Home homeless program from budget cuts.

At this point, $20 million of the mineral lease revenue has been appropriated for capital improvement projects, leaving about $70 million unspent. There is some talk among council members that maybe the city’s policy of restricting ways in which the Barnett Shale money is (or isn’t) used might have to be rethought.

At this point, $20 million of the mineral lease revenue has been appropriated for capital improvement projects, leaving about $70 million unspent. There is some talk among council members that maybe the city’s policy of restricting ways in which the Barnett Shale money is (or isn’t) used might have to be rethought.

“We are reviewing it,” said council member Jungus Jordan. “This is a rainy day we are experiencing. We changed the policy to use the $15 million for street improvements, and we may do that again or approve some other general funding project. This year we may need to use it for stopgap measures like the money needed to operate libraries. But … we cannot rely on the gas money because the price of gas fluctuates. You cannot depend upon it to fund programs each year. So we have to be careful about it.”

For the past few years, there has been talk at city hall about lobbying the FAA to change its policy that requires income from wells drilled on airport properties to be spent on the airports. The city’s three airfields — Meacham, Spinks, and Alliance — each have a total operating budget of about $5 million a year, covered by rents and landing fees. The federal government pays for about 80 percent of the capital improvements like runway extensions, and the state makes up for most of the rest.

The reality is that Fort Worth airports have little to spend the gas lease money on — now at $27 million — because they have no passenger service. The FAA policy was designed to keep governments from drilling lots of gas and oil wells on airport property that would create safety issues; they didn’t want flammable drilling rigs next to runways. But the Barnett Shale drilling is done with horizontal rigs, and the wells are nowhere near the runways.

The FAA policy has nine approved uses for mineral lease money at airports, mostly for airport maintenance and capital improvements. The idea floated by some city staffers and business leaders is to add a 10th approved use: transportation infrastructure projects done by the government entity that owns the airport. With so many shale-drilling regions starting all over the country, many have figured that local congressmen from those districts would get behind such a proposal, which could benefit many local governments and broad regional transportation needs.

Jordan said he would like to explore getting the FAA policy changed to free up some of that money. But nothing has been done at this point, and a city with a $59 million budget shortfall — and $1 billion in transportation infrastructure needs — has $27 million sitting in the bank going unused.

At the center of the budget debate is, essentially, the question of what the core of city services should be. The city staff has defined “core services” as “health and safety issues,” meaning that police and fire will not get touched but that programs serving specific population segments — and not the entire city — are liable to get shaved or lopped off altogether.

Some of the budget cuts seem small, but to those who benefit from the services, any cut will have an impact.

Some of the budget cuts seem small, but to those who benefit from the services, any cut will have an impact.

Imagination Celebration has been a Fort Worth community arts program since 1977, serving 120,000 students last year – most from the Fort Worth ISD.

The progam, which received $50,000 from the city last year, won’t get it next year. The nonprofit organization has a total budget of $600,000, mostly supplied by federal and state grants and private foundations. Longtime director Ginger Head-Gearheart said the loss of $50,000 would have an impact.

“We will definitely have to cut some staff and cut some of the programs,” Head-Gearheart said. “I understand the budget issues, but these are arts programs for poor kids. I know we need pools and libraries and community centers for these kids. But the arts programs do a lot as well. It just seems this budget is cutting out so many programs for the poor kids.”

Councilman Carter Burdette said at a recent budget workshop that programs that serve subsets of the Fort Worth population “will have to find other ways to pay for them, either by raising money from private donations or paying fees by the people that use them. We have to protect the core services, things the city does for everyone, like police protection and street maintenance. But during times like this, these other programs have to be reduced.”

Others on council think the definition of core services should be much broader. Kathleen Hicks said the budget cuts have been piled too heavily “on the backs of the working poor” and that pools and libraries are indeed core services.

“While there is real anger out there, there is also a feeling of resignation among the working poor I have spoken with,” Hicks said. “People think they are always the ones to face the service cuts, and they feel that the city council believes they are the point of least resistance. I am extremely concerned that we may find some short-term gain, but we will be facing long term consequences that will haunt this city for years to come.”

Council member Frank Moss agreed. “Maintaining public safety and streets has to be a high priority,” he said. “But I don’t think the city staff realizes how important the libraries are during an economic downturn. I also think there will be consequences to cutting late night and after-school programs and the pools. These cuts do impact inner city youths. We have been told that public safety is a big issue when we think about budget cuts, but these programs are a part of public safety. They keep kids off the streets. That’s how I look at it.”

Mayor Moncrief said at one budget workshop that the city’s public safety is the number-one concern. “If a city isn’t safe, you are not going to want to live there if they have a library or not,” he said.

DeBose agrees, but she also said the city didn’t touch some programs because of “wealthy influence.” The Van Cliburn Foundation gets $100,000 from the city annually, and the proposed 2010 budget does not touch that. City council recently approved using $250,000 of gas well funds to install a statue downtown of John F. Kennedy near where he made his last speech before being assassinated in Dallas in 1963.

The Fort Worth Zoo will get $5.4 million in city funds next year, under a contract that runs through May of 2011. The co-chairs of the zoo’s board of directors are Ramona Bass of the Bass family and Kit Moncrief, the mayor’s wife.

“Fort Worth is saying to us they don’t have any money for basic services, but they find $250,000 for a Kennedy statue,” DeBose said. “Why can’t they go to the Van Cliburn Foundation board or the zoo board and tell them the financial problems they are having and ask those boards to help out a bit? These folks could easily raise the money they needed, but they aren’t even being asked to. We can’t do that over here, but the city doesn’t seem to care.”

Fort Worth city staffers and council members say they aren’t raising any taxes to cover the budget shortfall, but that is misleading. Water, sewer, and storm water utility bills would go up $2.10 a month for the average homeowner under the proposed budget, bringing into the city an additional $9.5 million in revenue.

Parking meters would go up from $1 an hour to $1.25. Parking ticket fines would be raised by $5 to $25, depending on the violation. Library fines for overdue children’s books would go up from 15 cents a day to 25 cents.

Those who favor keeping the city pools and the two branch libraries open say the city should consider increasing fees for the users of the two entities to keep them afloat. But Richard Zavala, director of the Parks and Community Services Department, said the pools cost the city more than $8 to operate for each visitor and that the city charges children only $1 a day.

When the city’s library department suggested saving more than $800,000 a year by closing the Meadowbrook and Wedgwood branches, it set off a community firestorm. The reasoning behind the suggested closings was that both were just a few miles from larger regional branches and that both, built in the early 1960s, were old and outdated.

But the library system had gone through tough budget cuts last year by reducing staff and hours. Councilmen Jordan and Moss, whose districts contain the two branches, have been bargaining behind the scenes to save them.

“We have heard from more citizens on this library issue than any other,” Jordan said. “Libraries are a core function of government. I agree that Wedgwood is an inadequate facility. But the solution is not closing it. The solution is finding a better facility.”

Moss added that “the libraries took a major cut last year, and we can’t do that again. This is an essential city service.”

The solution may be to close all of the city pools, including Forest Park, which under the original proposal was to remain open and provide children’s swimming classes. Closing six of the seven city pools would save the city almost $445,000. But if the Forest Park pool is also closed, that number would jump considerably. Zavala said the pool needs a new liner and upgrades before opening next year, costing the city about $1.2 million. That money could be transferred to the library department to keep the two branches open.

The city staff has tried unsuccessfully in the past few years to close the pools. Their reasoning: The seven pools combined get only about 50,000 visits each summer, it is a service that is used only for three months out of the year, the pools are very old and need costly upgrades to comply with public health requirements, and there are other options for residents who want to swim.

When Zavala was asked by council about swimming options for inner-city kids, he replied “places like Hurricane Harbor.” Tickets for a one-day admission to the water park cost $25, parking is $10, and there is no public transit to get there. Maybe it’s not an option for everybody.

There is no doubt that city finances are reflective of the national economic problems. Dallas, for example, is looking to cut $190 million from its budget, more than three times as much as Fort Worth.

There is no doubt that city finances are reflective of the national economic problems. Dallas, for example, is looking to cut $190 million from its budget, more than three times as much as Fort Worth.

Pension funding for city retirees is also at issue, as is the rising healthcare costs for city employees. But these are issues for every government and private business, not just Fort Worth. Poor financial planning has led to many of these problems, however.

Over the next few weeks, there will be backroom deals between council members and city staff to revise some of the cuts, but one thing is certain. Some basic city services that citizens have relied upon will be gone; citizens will not see a tax increase, but they will pay higher fees; city streets will be further neglected; and valued community centers will offer fewer programs.

Citizens are offering some other solutions. Como’s DeBose suggests funding the late-night community centers program through the tax-supported Crime Control and Prevention District (CCPD) because the programs do reduce crime. “The CCPD has gang intervention programs that are not going to be cut, and I think we could find a way to use the police funding to keep the late night programs operating,” she said. “In some ways, these programs are related to gang intervention.”

Most on the council seem to regard the idea of raising the property tax rate by a penny or two as an unsound political move. But some believe it could be justified to the voters. Parks and Community Services Advisory Board vice chairwoman Gale Cupp said, “When the citizens of this city see all the programs that are cut, there will be a movement to raise property taxes a penny or two to make up for that.”

Wedgwood neighborhood resident Thomas wants to have voters decide how the city’s gas well bonuses and royalties are spent. “The property that is leased is public property,” she said. “We never hear what they plan to use that money for. A good policy would be to [tell] the voters fairly soon what the city’s plans are for that revenue. If there is enough there to fill the funding gap of some of these services being cut, then let the voters decide if that is how they want to use that money.”

Are city services basically nothing more than paving streets, picking up garbage, and providing police and fire protection? Or is it more than that, giving citizens a quality of life that includes an emphasis on good neighborhood development and quality of life issues?

“The easiest cuts to make are [the ones affecting] people who won’t be as vocal, and the poor in our community have less voice than the wealthy,” DeBose said. “But these are the people that use the community centers and libraries and pools. These are the people who might need day labor jobs to get back on their feet. And these are also people who have worked hard through the years to improve their neighborhoods.

“When I look at the programs that were chosen to be cut and the process that went into it, I just get heartburn,” DeBose continued. “And I look at all these kids and realize that they are being ignored in this budget. But no one wants to talk about what the real cost will be. There is going to certainly be a financial cost, but there will also be a cost in human terms, as we are taking away some of these kids’ futures.”

At the Como Community Center, neighbors are mad about another program that’s being reduced. About 200 kids now participate in the after-school-care program each day. That would be capped at 50 under the current budget proposal, cutting six more jobs.

“Let’s see, we have the late night program that police have told us has reduced crime, and we are going to get rid of it,” DeBose said last Friday night as she visited the community center. “Then we’re going to make it very difficult for kids to get positive programs after school. And then, no place for them to swim in the summertime.

“You can see what the consequences will be,” she continued. “These programs have helped reduce crime and make this city safer, but now you are going to have kids on the street with nothing to do, and we all know what will happen. There won’t be money saved. In fact, it will end up costing the city more because fighting more crime costs lots of money.”

Standing near DeBose were Kim and Tyrone Manning, who have a son on the Como Lions football team. They watched him horse around with his friends as the team members waited to get their helmets. The city youth football league is not subsidized by the city. The Mannings and other families pay $65 per kid a year for them to play football.

“There are a lot of kids in this neighborhood who are borderline,” said Tyrone Manning, who works at Lockheed-Martin as a materials handler. “These programs allow the kids to stay away from the danger out there. And the people in this place, from the volunteers to the staff, are positive role models and mentors. The kids listen to them.”

Kim Manning also sees little logic in the community center cuts. “I understand that cuts need to be made to balance the budget, and I understand that every program needs to be looked at,” she said. “But the city tells us that we have to work at making our neighborhood nicer and safer, how important that is, and then they want to take away the programs that help us do that.”

As for 12-year-old Tyrone Manning Jr., who plays football, basketball, and track in the community center programs, not being able to practice his sports there after school “would make me real mad,” he said. “It’s just fun to be with your friends and play sports. I don’t know why they want to take that away from us.”