Going on a water-only hunger strike for 32 days made Ted Glick, co-founder of the Climate Crisis Council, feel extremely weak – but nowhere near as bad as he felt when he realized that his efforts, and that of 200 other climate activists in Texas and around the country, had gone for naught.

The New Jersey native was one of 200 people who fasted in a last-ditch effort to get Congress to take a strong stance on global warming measures in the months leading up to the Copenhagen Climate Conference. He was one of nine who fasted for at least 25 days. Many scientists believe the November conference represents the last chance for governments around the world to adopt measures that could slow down global warming just enough to prevent catastrophic changes to the Earth’s climate.

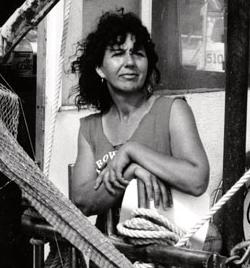

Diane Wilson, one of the Texans who fasted, said that she was willing to risk her own health because it takes bold strokes to get noticed by anyone. But, she said, it wasn’t enough.

Diane Wilson, one of the Texans who fasted, said that she was willing to risk her own health because it takes bold strokes to get noticed by anyone. But, she said, it wasn’t enough.

“I believe in bold action,” said Wilson, who has participated in eight other hunger strikes but said this was her longest. “I think you have to go to those places and put yourself at risk. It’s too easy when they can’t see you. You have to get right in their faces. We should have done the hunger strike right on the steps of the Capitol so they would have had to pass us every morning.”

Glick and the others had hoped that a bill considered last month by the U.S. House’s energy committee would be strengthened to require that carbon emissions be reduced by 25 to 40 percent, a level that scientists believe might stop the tumble into global ecological, economic, and humanitarian crises. That didn’t happen, however, and the bill, sponsored by U.S. Reps. Edward Markey and Henry Waxman, calls for cuts in carbon emissions of only five percent below 1990 levels. It’s expected to be voted on by the full House this week.

Tim Locke, an Austin environmentalist, thinks that the bill will tell the rest of the world whether this country is serious about doing something about climate change. As it stands now, he said, “This bill says we’re not serious.”

Three Texans fasted between 25 and 40 days, including two key organizers of the effort: Locke, the director of the Texas Climate Emergency Campaign, and Wilson, a fourth-generation fisherwoman and environmental activist from the Texas Gulf Coast, leader of Calhoun County Resource Watch, and environmental author. Locke fasted for 32 days, though he did supplement his diet with juices; Wilson went for 40, with a doctor-ordered four-day break in the middle.

For environmentalists like Wilson and Locke, it’s as if they’re standing near a precipice, trying to keep the world from going over – and being ignored.

Glick said that he lost about 30 pounds during the fast and constantly felt weak, limping along at about 25 to 30 percent of his normal energy level. His doctor, he said, was very concerned for his health, though he himself never believed he was in any serious danger. The worst he felt throughout the ordeal was when the he realized that the sacrifice had been for nothing.

“I felt depressed and disillusioned,” he said. “I was like that for the last month, and I’m just now coming out of it. I was taken aback by how weak the bill was, and I’m sure I would have felt the same way whether I was fasting or not.”

An overwhelming majority of scientists believe that the Earth is at a point of no return with regard to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. They say that irreparable damage has already been done to the planet’s ecosystem. However, one influential group of scientists gives us a 50/50 chance of avoiding disastrous climate change.

Two years ago, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a scientific research group consisting of more than 2,500 scientists from around the world (including about half from the United States), concluded that U.S. emissions must be cut by 25 to 40 percent if there is to be an even chance of avoiding a planet-wide rise in temperature of two degrees Celsius. That seemingly insignificant heating up, they believe, will lead to disastrous outcomes, including 40 percent of the world losing half its drinking water.

In addition to the 25 to 40 percent cut in carbon emissions, the activists wanted a moratorium on building new coal plants and other provisions. But the bill was approved by the committee without any of those changes. Now they fear that getting even the neutered version of the legislation passed by Congress will require a series of further compromises at the hands of lawmakers who, the group’s leaders said, are in the pockets of oil and gas and coal companies.

Locke said neither politicians nor the general public understand the immediacy of the problem and the depth of the dangers the planet is facing.

“We’re trying everything we can think of to bring attention to this issue,” he said. “It [the hunger strike] didn’t get the attention that we wanted. I think it’s because politicians don’t know what’s about to hit them.”

According to renowned scientist Richard Seager at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, wind and weather patterns have already changed, and some areas of the U.S will experience a permanent drought condition.

“The climate of the southwestern United States will be in a perpetual drought condition,” Locke said, quoting the report. “Most of Texas west of I-35 will become like the climate of Nevada or Arizona. We’ll lose our water.

“In far East Texas, they may get even more water because of big storms that will come off of the Gulf,” he continued. “You’ll see more flooding.”

Locke said he spoke to Seager, who believes that Texas has already passed into a permanent drought and will be feeling its effects by 2050.

About 90 percent of the world’s top scientists, the IPCC included, think that we are already at the point of no return and that the world’s temperature will inevitably rise two degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels. If that happens, there will be no way to stop the temperature from rising another two degrees. That, scientists say, is the ecological tipping point, at which the permafrost in Siberia and Canada could melt, releasing the untold amounts of lethal methane gas and potentially making the Earth unlivable for human beings.

Locke said that there is little hope at this point for changing the contents of the bill but that his group will keep trying.

“We’re back to organizing in congressional districts, trying to get meetings with members of Congress, trying to educate them on what’s happening,” he said. “We have to keep trying, and that’s what we’re going to do.”

Glick, who came up with the idea for the fast, said that his organization is in contact with a group in Australia that is planning another long-term fast to coincide with the Copenhagen conference. The groups are considering a “rolling fast” in several countries.

“This isn’t something that we can slowly ease ourselves into over the next 30 or 40 years, little by little, and hope things will get better,” said Glick, who has been arrested four times in the last three years for civil disobedience related to climate change protests. “The natural processes at work … just don’t allow us to take a slow path.”

Wilson said she usually doesn’t target politicians with her protests because she believes that they’re too timid. This experience only reinforced that belief.

“When I started, I went to the most liberal Democrat anywhere in my home area,” she said, “and that person told me that I was a maverick and a nut and they were not going to commit political suicide” by supporting the measures she and the other environmentalist are seeking.