A flamenco dancer shimmied and snapped her fingers for the large crowd of local and state politicians, employees, and reporters who converged on Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport on May 1 to celebrate American Airlines’ new nonstop service to Madrid. Servers handed out glasses of wine, and people stood in line for fancy appetizers.

The mood was festive despite a deep recession that has businesses slashing their travel costs, families postponing vacations, and the airline industry reeling from revenue losses.

Daniel P. Garton, executive vice president of marketing at the Fort Worth-based airline, was preparing to speak to a large crowd that included Texas First Lady Anita Perry, U.S. Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, and Fort Worth City Council member Kathleen Hicks. But he took a few moments to speak with Fort Worth Weekly on the industry’s recent woes, from the struggles to pay for fuel in 2008 when oil was selling at a record $147 a barrel to staying afloat in 2009 with financial markets drying up.

Daniel P. Garton, executive vice president of marketing at the Fort Worth-based airline, was preparing to speak to a large crowd that included Texas First Lady Anita Perry, U.S. Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson, and Fort Worth City Council member Kathleen Hicks. But he took a few moments to speak with Fort Worth Weekly on the industry’s recent woes, from the struggles to pay for fuel in 2008 when oil was selling at a record $147 a barrel to staying afloat in 2009 with financial markets drying up.

“You feel like it’s out of the frying pan and into the fire,” he said.

It’s one of several metaphors getting tossed around to describe the company’s financial climate these days.

” ‘Perfect storm’ is a phrase that gets used way too much, but if you look at American … ,” company financial spokesman Andrew Backover said recently, before he launched into a description of the airline’s rocky status.

In the airline industry, “Everybody has a cold; American Airlines may have a touch of pneumonia in a couple of areas,” analyst and consultant Bob Mann, of R.W. Mann & Co., said.

Losing this patient would be particularly painful around these parts. American is the primary carrier at D/FW Airport, which in turn is a vital spark plug for the North Texas economy.

“There is no question that American Airlines is one of the biggest employers in the D/FW area and accounts for about 80 percent of all the air passenger traffic at D/FW Airport,” said Bernard Weinstein, director of the Center for Economic Development and Research at the University of North Texas. “If they were to somehow disappear, that would have a devastating impact.”

The tragedy of 9/11 spurred an industry landslide. Every major airport in the country was shut down for several days. Congress, federal agencies, and airline officials frantically tried to boost security, but even after the airports were open again, people were scared to fly for a while. An estimated 100,000 workers at the country’s major airlines were laid off.

Shortly after that, fuel prices began escalating. The industry lost untold billions of dollars in revenue, and airlines began flying into bankruptcy courts. Many employees saw their pay slashed and hours increased.

American Airlines is among the world’s largest carriers, employing more than 80,000 people worldwide, including about 25,000 locally. By 2003, however, it too was teetering. The company staved off bankruptcy, saved many of its jobs, and struggled onward.

Lately things have been bad enough that news reports about an American Airlines pilot who flunked a breath test prior to working a flight from London to Chicago registered as only a small blip on the radar.

Parent company AMR Corp. lost $375 million in the first quarter of 2009 – up from $341 million during the same period in 2008.

Employees are picketing and grumbling about exorbitant salaries paid to executives. The airline has had a contentious relationship with its workers ever since former chairman Robert Crandall began his autocratic rule in the 1980s. But now, for the first time in American’s history, all three of its labor groups – pilots, flight attendants, and transport workers unions – are in mediation at th e same time.

e same time.

The company’s fleet of airplanes is aging and dominated by gas-guzzling MD-80s. Reports of maintenance lapses resulted in the entire fleet of MD-80s being temporarily grounded amid increased scrutiny from federal inspectors last year. The airline and the Federal Aviation Administration appear to be in a pissing match that could have serious consequences.

Former flight attendant Alicia Lutz- Rolow arrived in Fort Worth last year to receive an award from American but instead took the podium to accuse company executives of greed and corruption. Her comments later aired on MSNBC. Now she has published The Plane Truth, a scathing attack on the company and its management.

Meanwhile, a share of the company’s stock is selling for less than a six-pack of Bud Light. The same share would have sold for $40 several years ago.

But this ain’t the company’s first rodeo, or perfect storm, or frying pan, or case of pneumonia. While the auto industry and others have been begging for federal bailouts, American has tended to business, made adjustments, and appears to be maneuvering itself to weather the economic squalls.

A recent stroll through hallways at American Airlines headquarters revealed a slight darkness – literally. Long rows of light fixtures designed to hold three fluorescent bulbs had been stripped of their middle bulbs. Hundreds of bulbs throughout the building were removed almost two years ago.

“I noticed the difference in the lighting the first day,” company spokesman Tim Wagner said. “Since then I don’t even notice it.”

Worn-out carpet was replaced with carpeting made of recycled material, automated paper towels systems were installed in bathrooms to discourage waste, and moisture-monitoring systems were added so the lawn isn’t over-watered.

Even the small lightbulbs in the candy machines have been removed.

“Being more efficient is good for us and good for the environment,” Wagner said.

American Airlines initiated the efficiency programs to help the company bottom line by squeezing out some savings, then set about last summer squeezing some extra income from passengers. Extra charges for checked baggage angered many travelers but helped the airline keep afloat at a time when the company was reeling from record-high fuel prices.

With the airline tightening its belt, company officials expect workers to do the same. Employees, however, see things differently. They say their belts are already so tight they can barely breathe. Labor groups gave up pay and benefits in 2003 to help save the company from bankruptcy. Now pilots, flight attendants, and transport workers – the three main labor unions – are seeking repayment for their loyalty.

“It’s our time to reap the benefits since we’ve borne the brunt of all the cuts,” said Frank Bastien, national communications coordinator at the Association of Professional Flight Attendants.

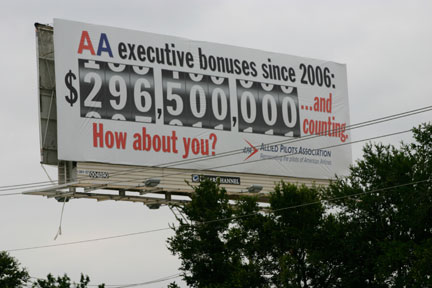

Employees point accusing fingers at the hefty salaries and bonuses given to top executives since 2003. They say it’s time for CEO Gerard Arpey (who made about $5 million in salary, stock grants, and options last year) and his management team to spread the wealth and share the pain. The pilots’ union rented a billboard beside Highway 183 that blasts executive pay. The billboard is near the highway exit that leads to American’s headquarters and to D/FW Airport’s south entrance.

In April, several hundred baggage handlers, mechanics, and other transport workers picketed at headquarters to protest executive pay, which they say has totaled $300 million during the past four years for the top managers, despite a decade marked by financial losses. Their complaints were leveled at the same time the nation as a whole was lambasting exorbitant CEO salaries and bonuses at giant insurance companies, banks, and other corporations reeling from mismanagement and asking for taxpayer bailouts.

“In past years there was more acceptance by the general society for [high CEO pay], but now when the average CEO makes 344 times what their average workers make, people are saying, ‘Where does this stop?’ ” said Jamie Horwitz, a spokesman for the Transport Workers Union. American is projected to lose hundreds of millions of dollars this year, he said, so, “Why is anybody taking any bonuses?”

Bastien said unions conceded about 30 percent of their pay and benefits during the bankruptcy scare of 2003 but have recaptured only about 8 percent since then. Executives received smaller bonuses this year than in years past, but “It’s a lot more than we got, because we got no bonuses,” he said. “We still are working on pay scales that were sharp reductions of what we had.”

Executive compensation at American has been less than officials would have received if the airline had been financially healthy. Management pay has hovered around the median for that peer group, while frontline labor at American is paid among the highest in their peer group, corporate spokeswoman Missy Latham said.

“There is a market for each group of talent,” she said. “When you look at our frontline mechanics, our pilots, our flight attendants, the folks at American are making more than at other airlines.

“Our pilots can proudly say they make more than any other pilot at any other airline for the amount of time they fly,” Latham said.

Some would say pride is the problem. A longtime pilot, now retired, said upper management at American views its labor force as inferior.

“Arpey took over with the best of intentions and did a great job, but that embedded culture is more than even the boss can overcome,” said the pilot, who asked not to be identified. “It was supposed to be a policy of shared sacrifice. Indeed, Arpey and others took huge cuts and turned down some bonuses and reduced salaries. That went along fine until the last couple of years, when large sums of money in stock options started going to the top management.

“Arpey took over with the best of intentions and did a great job, but that embedded culture is more than even the boss can overcome,” said the pilot, who asked not to be identified. “It was supposed to be a policy of shared sacrifice. Indeed, Arpey and others took huge cuts and turned down some bonuses and reduced salaries. That went along fine until the last couple of years, when large sums of money in stock options started going to the top management.

“They are taking pay raises, yet the pay for employee groups has been pretty stagnant,” he said.

The rash of airline bankruptcies following 9/11 wiped out the pay and pensions of many pilots, mechanics, and flight attendants. Many of those employees left the industry or started over elsewhere at lower wages. Earning less could be a sign of the times … and of the future.

“They’re saying, ‘We want to go back to what we were making in 2003,’ ” Backover said. “The environment has changed. Demand has changed. Profits have changed. Costs have changed. Competition has changed. No one is going back to 2003.”

By avoiding bankruptcy, American maintained control of its decision-making and destiny but also found itself at a disadvantage in labor costs. Carriers that filed for bankruptcy restructured their labor contracts, cut pay, and added work hours. American did the same voluntarily and to a lesser degree, but still finds itself paying more than most other major carriers.

“They have a higher cost structure than just about any airline in the country, and that’s something they have to wrestle with,” Weinstein said.

Future labor contracts at American will reflect the changing times, Backover said.

“In the context of the new contracts, we have to be competitive,” he said. “The industry pay scale changed forever. It is what it is now – it’s not going to be what it was in the 1990s or ’80s.”

The venom flew when Alicia Lutz-Rolow released her self-published book The Plane Truth earlier this year. It characterizes American Airlines labor groups as selfless and devoted, while painting executives such as Arpey as instilling a “breed of greed” among management types who put profits above public safety. Three times since 2002, Lutz-Rolow has refused to work her scheduled flights because of what she perceived as safety issues. She is currently on leave and is planning to retire next month after more than 30 years in the skies.

The Los Angeles resident made headlines a year ago when she arrived in Fort Worth at the C.R. Smith Museum to receive a Golden Heart Award for helping save a passenger’s life. Instead, she used the stage to blast her bosses.

“A couple of the top executives who were getting ready to get these incredible bonuses were there, and I wanted to direct my anger at them,” she said. “They were all standing there, and they had their mouths open. They had no idea this was coming.”

Lutz-Rolow refused the award and accused the airlines of cutting corners on safety. MSNBC asked her to fly to New York for a live on-set interview, but Lutz-Rolow declined. She later gave an interview reiterating her claims, but she came across as disheveled and spacey and was cut off fairly quickly by the TV news staffer.

Her tome turned out to be a long, rambling rant filled with inaccuracies. Bastien, the flight attendants’ spokesman, said he doesn’t agree with the author’s claims that the flying public is at risk and that the American Airlines maintenance program is shoddy.

“I can’t say I’ve received reports on flight attendants feeling uncomfortable,” he said. “Nobody wants to run an unsafe operation. I can’t say I would have any misgivings as far as American Airlines operating an unsafe airplane.”

Still, in the past couple of years, public officials have questioned American and other carriers on their maintenance practices, and an extensive FAA audit is currently under way at American. The Fort Worth company’s fleet, among the oldest of those owned by major U.S. carriers, is showing its age.

“All these MD-80s that started rolling in the 1980s – the older they get, the less reliable they are,” said a transportation reporter for a national magazine who asked for anonymity. “Gas prices are down now, but MD-80s are not fuel efficient, and if gas goes up it’s going to hurt. Compared to newer planes, you get a 25 percent savings just by turning the keys on a Boeing 707.”

American, aware of the problem, is moving to upgrade the fleet, which includes about 34 outdated and discontinued wide-body Airbus A300s. All will be retired by year’s end, Backover said. The airline retired 20 of its MD-80s last year but still has about 270 of the gas-guzzling craft flying, with an average age of 19 years. Over the next two years, about 76 of them will be replaced with Boeing 737s, which carry more seats and are about 35 percent more fuel efficient.

The company also has an agreement to buy about 42 of the more fuel-efficient Boeing 787s with an option for another 58 between 2013 and 2020.

One thing executives aren’t buying: any criticisms on how mechanics are maintaining that fleet.

One thing executives aren’t buying: any criticisms on how mechanics are maintaining that fleet.

Industry-wide concerns about airline maintenance came to a head last year after an FAA inspector complained to a congressional committee that Southwest Airlines was continuing to fly planes despite fuselage cracks. His attempts to ground the planes had been overridden by supervisors whom he accused of being too friendly with airline executives.

Congressional hearings in 2008 confirmed his complaint. Witnesses accused the FAA of regulatory lapses, and congressional leaders described a “culture of coziness” between agency officials and airline bosses.

“The committee’s investigation uncovered a pattern of regulatory abuse and widespread regulatory lapses that allowed 117 aircraft to be operated in commercial service despite being out of compliance with airworthiness directives,” U.S. Rep. James Oberstar, head of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, told the Los Angeles Times in 2008. “FAA needs to clean house, from the top down,” the Minnesota Democrat said.

Southwest Airlines was hit with a $10.2 million fine and yanked dozens of jets from service to receive the proper maintenance.

A reinvigorated FAA then turned its sights to American Airlines.

The company responded by temporarily grounding its entire fleet of MD-80s, causing the cancellation of about 3,000 flights and disruption of flight plans for hundreds of thousands of passengers.

At issue was a wiring harness. The FAA had issued an airworthiness directive in 2006 advising all airlines flying MD-80s to repair wiring in the wheel wells. American Airlines made the fixes but not exactly in the manner detailed by the FAA instructions.

American is one of the few airlines still performing its own maintenance in-house. The company considers its mechanics to be top-notch and didn’t flinch when their fixes varied slightly from the directive. After the hearings, however, the FAA wasn’t in a compromising mood.

“It was a sea change in how the FAA operated,” Wagner said. “It went from trusting the mechanics to do it to [where] now we advise our mechanics that they must perform that work to the letter of the law.”

The groundings were an expensive reminder to American of the FAA’s regulatory power. Company officials weren’t exactly contrite, insisting that the FAA’s take on the alleged wiring problem was overblown.

Mann, the airline consultant, said American’s clash with the FAA is “largely self-inflicted” and “needs to be repaired.”

Then in April, a Dallas Morning News article characterized American as a “persistent source of concern for regulators.” The story described an FAA “special audit” at American that might last for months.

Airline officials say the so-called special audit is actually business as usual and industry-wide, and that the FAA isn’t singling out the Fort Worth-based carrier for problems. FAA spokesman Les Dorr agreed that American wasn’t being singled out but said the audit marked a new level of scrutiny – and without the familiar coziness.

“This is the first time we’ve ever done one of these air-carrier evaluation programs [audits] at American,” he said. “This particular audit is different in the sense it’s being done by inspectors who don’t normally work on the airline. They are not necessarily intimately familiar with the way American does things, and it’s a fresh set of eyes.”

Wagner downplayed any hostility and described American’s relationship with the agency as “professional.”

Wagner downplayed any hostility and described American’s relationship with the agency as “professional.”

The national transportation writer described the relationship as “very testy” but predicted that the bad blood won’t last long. All airlines have ups and downs with the FAA, but both entities are interested in safe skies and generally come to

mutual understandings, he said.

Former American Airlines chairman Robert Crandall, who left his position in 1998, said in a 2006 CNBC documentary that he had never invested in an airline and never would, pointing to the more than 100 airlines that had gone bankrupt since the industry was deregulated in the late 1970s.

Prior to deregulation, the major airlines operated similarly to public utility companies, enjoying a cost-plus type of business model. The federal government controlled fares, routes, and profit levels. Afterward, a competitive market sent many major carriers and small airlines into bankruptcy.

“This is not an appropriate investment,” Crandall said. “It’s a great place to work, and it’s a great company that does important work. But airlines are not an investment.”

American has staggered under huge revenue hits since 2001. In between the shocks of 9/11 and the hammer of skyrocketing fuel prices, however, it did manage two profitable years.

“When the economy was recovering and growing, our two best years were 2006 and 2007,” Backover said. “We earned about $230 million in 2006 and about $500 million in 2007.”

That’s only about a 1.5 percent profit margin for those two years, but it beats losing $2 billion, as the parent company did in 2008. Three huge dominoes have to fall in American’s favor if the company is going to get back to profitability: The economy has to recover as it appears to be doing; fuel prices must remain reasonable, as they have been for the past year; and labor and management have to reach agreements without any strikes.

“The industry has always been cyclical,” Garton said.

Weinstein said American has cash on hand, unlike many other airlines, which will help it ride out the borrowing crunch without being at the mercy of banks.

“Everything I’ve been reading is that they have sufficient cash, and – barring any unforeseen double dip in the economy – they should be able to ride out the storm,” he said.

Mann, who was an airline executive from 1977 to 1992 at American, Pan Am, and TWA, said American has been through two rougher spots in its long history: the 1981-82 fuel shortages and the post-9/11 trauma. The airline survived both those punches and came back swinging. That experience and history should help it pull out of this dive, he said.

“They have the experience of having been through the prior difficulties – if you’ve seen it before, hopefully you didn’t forget it all,” he said.

Even the recently retired pilot who dislikes American’s arrogant management mentality believes the company will survive and prosper.

“I’m optimistic they’ll pull it off because American is still all-around as good or better than any of the carriers out there, and I know there is not a better pilot group in the industry,” he said. “The experience working there was phenomenal. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”